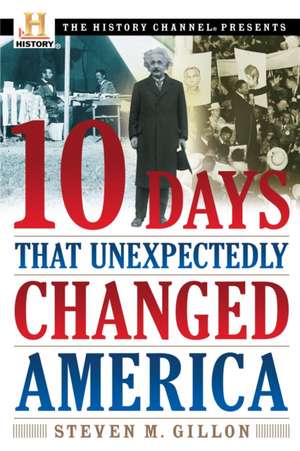

10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America: History Channel Presents

Autor Steven M. Gillonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America pinpoints pivotal days that transformed our nation. For the series and the book, The History Channel challenged a panel of leading historians, including author Steven M. Gillon, to come up with some less well-known but historically significant events that triggered change in America. Together, the days they chose tell a story about the great democratic ideals upon which our country was built.

You won’t find July 4, 1776, for instance, or the attack on Fort Sumter that ignited the Civil War, or the day Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. But January 25, 1787, is here. On that day, the ragtag men of Shays’ Rebellion attacked the federal arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts, and set the new nation on the path to a strong central government. January 24, 1848, is also on the list. That’s when a carpenter named John Marshall spotted a few glittering flakes of gold in a California riverbed. The discovery profoundly altered the American dream. Here, too, is the day that noted pacifist Albert Einstein unwittingly advocated the creation of the Manhattan Project, thus setting in motion a terrible chain of events.

Re-creating each event with vivid immediacy, accessibility, and historical accuracy, 10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America comes together as a history of our country, from the first colonists’ contact with Native Americans to the 1960s. It is a snapshot of our country as we were, are, and will be.

Preț: 101.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 152

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.42€ • 20.06$ • 16.16£

19.42€ • 20.06$ • 16.16£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307339348

ISBN-10: 0307339343

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Seria History Channel Presents

ISBN-10: 0307339343

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Seria History Channel Presents

Notă biografică

Steven M. Gillon is the resident historian of The History Channel and host of HistoryCENTER. Having taught at both Oxford and Yale, he is currently a professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Extras

1

May 26, 1637

Massacre at Mystic

On the moonlit night of May 26, 1637, Puritans from Massachusetts Bay Colony attacked a large Pequot village at a place called Missituck, located near the Mystic River in Connecticut. The assault began on May 25 with an all-day march through solidly held Pequot territory. As dusk approached, the seventy English, seventy Mohegans, and five hundred Narragansetts warriors led by Major John Mason and Captain John Underhill reached the outskirts of the Mystic settlement, where they decided to rest for a few hours. By 2 A.M. on the morning of the twenty-sixth, the English were poised to put an end to the war that had been raging between them and the Pequot for more than a year.

With the aid of clear skies and a brightly lit moon they began their final assault. Mason and Underhill divided their forces into northern and southern contingents and attacked through the two entrances to the village. According to their own accounts, Mason led his men through the northeast gate when he "heard a Dog bark, and an Indian crying Owanux! Owanux! Which is Englishmen! Englishmen!" After removing piles of tree branches that blocked their approach, Captain Underhill led his men through the other entrance with "our swords in our right hand, our carbines and muskets in our left hand." The Pequots, initially startled by the attack, quickly regrouped and pelted the invaders with arrows. Two Englishmen were killed and twenty others wounded. Some were shot "through the shoulder, some in the face, some in the legs."

Instead of engaging the Englishmen, many of the Pequots, especially women and children, stayed huddled in their wigwams. Frustrated that his enemy refused to fight by traditional European rules of engagement, Mason decided to burn the village. He lit a torch, setting fire to the wigwams. At the same time, Captain Underhill "set fire on the south end with a train of powder. The fires of both meeting in the center of the fort, blazed most terribly, and burnt all in the space of half an hour." Dozens of men, women, and children were burned alive. Mason observed that the Pequots were "most dreadfully amazed . . . indeed, such a dreadful Terror did the Almighty let fall upon their Spirits, that they would fly from us and run into the very Flames, where many of them perished." Another Englishman who saw the slaughter wrote: "The fire burnt their very bowstrings . . . down fell men, women and children . . . great and doleful was the bloody sight." After setting the fires, Mason ordered his men to "fall off and surround the Fort." From this vantage point, they slaughtered anyone trying to flee the flames. The carnage was so frightening that Uncas, a Mohegan sachem (chief) allied with the English, cried, "No more! You kill too many!"

The light of a late spring morning brought into full focus the carnage that had been perpetrated the previous night. The Pequot were reeling from the most gruesome act of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by European colonizers on American soil. Fort Mystic lay in smoldering ruins. Dwellings that once housed Pequot families were reduced to hot piles of ash, and the once formidable wooden palisade that surrounded Mystic was burning. Hundreds of Pequots were either dead or dying--mostly women, children, and elderly members of the tribe. The stench of burning human flesh filled the morning air. "It was a fearful sight to see them," observed William Bradford, who came to America on the Mayflower in 1620 and served as governor of Plymouth Colony, "thus frying in the fire and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the praise therof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to enclose their enemies in their hands and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enemy."

Major Mason considered his actions that day to be righteous, and he went to his grave believing that the violence at Mystic pleased the English God in true Puritan form. "Sometimes," he wrote, "the scripture declareth that women and children must perish with their parents . . . We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings." Mason, like most of the English commentators of the era, framed the conflict in terms of savagery and civilization; the "civilized" Protestants of the English empire were asserting their natural authority over "savage," pagan, and dark-skinned Indians. As the last fires at Mystic burned out, news of the tragedy spread throughout New England. A new and terrible era had begun.

***

The battle at Mystic had its roots in the initial contact in the early seventeenth century between English settlers and native peoples living in New England. The Pilgrims, who arrived in 1620, had the good fortune of encountering Squanto, a Wampanoag who helped the Pilgrims adjust to their new world. Within a few years, however, relations between the Pilgrims and local tribes soured. No matter how friendly the initial contact, it could not alter the English view of natives as untrustworthy savages. Indians, preached Anglican bishop John Jewell, were "a wild and naked people" who lived "without any civil government, offering up men's bodies in sacrifice, drinking men's blood . . . sacrificing boys and girls to certain familiar devils." Over the next few years the settlers stole native crops and acquired their land. In 1622, a militia captain killed eight friendly Indians, impaling the head of the sachem on top of the fort at Plymouth as a clear signal of their power. The Indians had a word for the white settlers: wotowquenange, which meant stabbers or cutthroats.

Both sides were already deeply suspicious of each other by the time Jonathan Winthrop and the six hundred Puritan settlers arrived on the shores of Massachusetts in June 1630. Unlike the mostly male crews of fortune seekers and laborers that landed in Virginia more than a decade earlier, the Puritans who founded the Plymouth Colony came as families--husbands, wives, children, and servants--seeking to locate permanently. They came to America determined to create a "Citty on the Hill," a utopia where individuals would work in common struggle to serve God's will. Winthrop wanted to escape a decadent England, with its Catholic queen, beggars, horse thieves, and "wandering ghosts in the shape of men." The Puritan mission was to tame the wilderness so their commonwealth would "shine like a beacon" back to immoral England.

The Puritan families wanted land and access to all of the bounties that the New World had to offer--a goal that put them in competition with the Indians for local natural resources. Most Puritans viewed Indians as dangerous, temporary obstacles to permanent English settlement in New England, not potential partners in the development of a new society. "The principall ende of this plantacion," their charter stated, was to "wynn and incite the natives of [the] country, to the knowledg and obedience of the onlie true God and Savior of mankinde, and the Christian fayth."

The Puritans came to America prepared to use force to achieve their ends. The Massachusetts Charter instructed settlers "to encounter, expulse, repel, and resist by force of arms" any effort to destroy the settlement. The settlers who arrived in Massachusetts aboard the Arabella were told to "neglect not walls, and bulwarks, and fortifications for your own defence." They brought with them five artillery pieces, skilled artisans who could make weapons, and a handful of professional soldiers. Shortly after arriving they set up a militia company. All males between the ages of sixteen and sixty were expected to serve.

Within the first three years as many as three thousand English had settled in the colony. By 1638, the population had swelled to eleven thousand. As the colony grew, the Puritans laid claim to land owned by the Indians. As God's "chosen people," the Puritans felt entitled to the land occupied by native tribes, often using Scripture to justify the outright seizure of territory. The new land was an untamed wilderness and their job was to subdue it for the glory of their God. The Puritans also offered secular justifications for taking possession of the land. Winthrop created a legal concept called vacuum domicilium, which proposed that Indians had defendable rights only to lands that were under cultivation. "As for the Natives in New England, they inclose noe Land, neither have any setled habytation, nor any tame Cattle to improve the Land by," Winthrop reasoned. If they left Indians land "sufficient for their use, we may lawfully take the rest, there being more than enough for them and us."

The Puritans' most powerful weapons in seizing Indian land were neither laws nor guns, but microbes. Over the centuries, Europeans had been exposed to and, through a process of evolution, developed immunity to a host of viruses. Indians, isolated on a distant continent, had never been exposed to the deadly microbes and therefore had no immunity. Smallpox was the biggest killer, but syphilis and various respiratory diseases added to the death toll. Tens of thousands of Indians died in the first year after the arrival of the English. By some estimates, disease killed 75 percent of the tribes in southern New England in less than two years. An Englishman wrote that the Indians had "died on heapes, as they lay in their houses, and the living that were able to shift for themselves wouyle runne away and let them dy, and let there Carkases ly above the ground without buriall."

As more Puritans disembarked in America, their settlements expanded farther west and south, eventually bringing them into contact with the Pequot. There were roughly thirteen thousand Pequots occupying the two thousand square miles of territory between the Niantic River in Connecticut and the Wecapaug River in Rhode Island. Little is known about the Pequot before their contact with Europeans. One historian described them as the "most numerous, the most warlike, the fiercest and the bravest of all aboriginal clans of Connecticut." Like other native tribes in southern New England, they depended on farming, hunting, and fishing for survival. The main difference between them and other nearby tribes, such as the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and Mattabesic, was that the Pequot built fortified villages. By 1637 they had constructed two large fortified hilltop villages--at Weinshauks and Mystic. In addition to these forts, they built smaller villages nearby containing as many as thirty wigwams, which were surrounded by a few hundred acres of cultivated land.

Highly organized with a powerful grand sachem and tribal council, the Pequot managed to establish military dominance over the other tribes in New England. In an effort to monopolize trade with early Dutch explorers, the Pequot subjugated nearby tribes. By the 1630s, the Pequot were the dominant political and military force in the area. Not only had they established extensive trading networks throughout the region, but they also occupied some of the region's most fertile soil.

Just as the English were planning to expand into Pequot territory, the tribe was decimated by disease. By 1634, the tribe that had numbered thirteen thousand a few years earlier now had only three thousand. John White, a planter in New England, wrote that "the Contagion hath scarce left alive one person of an hundred." Whole Indian tribes were decimated--too sick to hunt, fetch wood for fire, or take care of one another. Their bodies were full of bursting pox boils; "their skin cleaving by reason thereof to the mats they lie on. When they turn them, a whole side will flay off at once, and they will be all of a gore blood, most fearful to behold." The Puritans believed that the epidemics were gifts from God. "If God were not pleased with our inheriting these parts," Puritan Jonathan Winthrop wondered, "why did he drive out the natives before us? And why doth he still make room for us, by diminishing them as we increase?"

The once powerful Pequot found themselves under assault from all directions. Not only were they reeling from disease, they faced new economic competition. The Pequot occupied land that was rich in wampum--small sea shells drilled and strung together into beads. Until the arrival of the Europeans, wampum had served as a medium of exchange and communication for many tribes. They used it to create the insignia of sachems, command the service of shamans, console the bereaved, celebrate marriages, end blood feuds, and seal treaties. The Dutch, and later the English, however, recognized the economic value of wampum and started using it as a form of currency. Initially, the Pequot benefited from a lucrative trading system that involved exchanging wampum and furs for European manufactured goods. Eventually, however, the English decided to make their own wampum. Using steel drills, they produced large quantities of wampum, driving down its value and undermining the source of the Pequot's economic power.

The Pequot were divided over how to respond to the new economic threat posed by the English. The sachem Sassacus, deeply distrustful of the English, called for building an alliance with the Dutch to try to repel the English. The sub-sachem Uncas, who had married Sassacus's daughter, opposed these efforts. Believing it was futile to resist the more numerous and well-armed English, he advocated cooperation. (Uncas would be forever remembered as the fictionalized character in James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans.) The debate between these two powerful men ripped the tribe apart at a critical moment. After a series of heated debates, the tribal council sided with Sassacus and forced Uncas to leave the village. An angry Uncas formed a separate tribe, the Mohegan, and joined forces with the English in an effort to destroy his former tribe. Decimated by disease and torn apart by rival factions, the Pequot had never been more vulnerable.

The English moved quickly to take advantage of the opportunity. The immediate cause of the horrific attack on Mystic was revenge for the deaths of two Englishmen. In 1634, Captain John Stone, an English merchant, and his crew were found dead on their ship on the Connecticut River. Stone fell far short of the God-fearing ideal for an Englishman of the times. He was a notorious drunk, cheat, and liar. At the time of his death he was in trouble for stealing a ship full of Dutch trade goods from the Dutch governor of New York after a night of hard drinking. (Stone got the governor drunk as a diversionary tactic.) Informants from the Narragansett told colonial authorities that the Pequot ruthlessly murdered Stone and his men in their sleep. The Pequot told a different story. They claimed that Stone had taken two Indians captive. When Stone refused to release them, they took the ship by force. "This was related with such confidence and gravity," Winthrop said, "as having no means to contradict it, we inclined to believe it."

May 26, 1637

Massacre at Mystic

On the moonlit night of May 26, 1637, Puritans from Massachusetts Bay Colony attacked a large Pequot village at a place called Missituck, located near the Mystic River in Connecticut. The assault began on May 25 with an all-day march through solidly held Pequot territory. As dusk approached, the seventy English, seventy Mohegans, and five hundred Narragansetts warriors led by Major John Mason and Captain John Underhill reached the outskirts of the Mystic settlement, where they decided to rest for a few hours. By 2 A.M. on the morning of the twenty-sixth, the English were poised to put an end to the war that had been raging between them and the Pequot for more than a year.

With the aid of clear skies and a brightly lit moon they began their final assault. Mason and Underhill divided their forces into northern and southern contingents and attacked through the two entrances to the village. According to their own accounts, Mason led his men through the northeast gate when he "heard a Dog bark, and an Indian crying Owanux! Owanux! Which is Englishmen! Englishmen!" After removing piles of tree branches that blocked their approach, Captain Underhill led his men through the other entrance with "our swords in our right hand, our carbines and muskets in our left hand." The Pequots, initially startled by the attack, quickly regrouped and pelted the invaders with arrows. Two Englishmen were killed and twenty others wounded. Some were shot "through the shoulder, some in the face, some in the legs."

Instead of engaging the Englishmen, many of the Pequots, especially women and children, stayed huddled in their wigwams. Frustrated that his enemy refused to fight by traditional European rules of engagement, Mason decided to burn the village. He lit a torch, setting fire to the wigwams. At the same time, Captain Underhill "set fire on the south end with a train of powder. The fires of both meeting in the center of the fort, blazed most terribly, and burnt all in the space of half an hour." Dozens of men, women, and children were burned alive. Mason observed that the Pequots were "most dreadfully amazed . . . indeed, such a dreadful Terror did the Almighty let fall upon their Spirits, that they would fly from us and run into the very Flames, where many of them perished." Another Englishman who saw the slaughter wrote: "The fire burnt their very bowstrings . . . down fell men, women and children . . . great and doleful was the bloody sight." After setting the fires, Mason ordered his men to "fall off and surround the Fort." From this vantage point, they slaughtered anyone trying to flee the flames. The carnage was so frightening that Uncas, a Mohegan sachem (chief) allied with the English, cried, "No more! You kill too many!"

The light of a late spring morning brought into full focus the carnage that had been perpetrated the previous night. The Pequot were reeling from the most gruesome act of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by European colonizers on American soil. Fort Mystic lay in smoldering ruins. Dwellings that once housed Pequot families were reduced to hot piles of ash, and the once formidable wooden palisade that surrounded Mystic was burning. Hundreds of Pequots were either dead or dying--mostly women, children, and elderly members of the tribe. The stench of burning human flesh filled the morning air. "It was a fearful sight to see them," observed William Bradford, who came to America on the Mayflower in 1620 and served as governor of Plymouth Colony, "thus frying in the fire and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the praise therof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to enclose their enemies in their hands and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enemy."

Major Mason considered his actions that day to be righteous, and he went to his grave believing that the violence at Mystic pleased the English God in true Puritan form. "Sometimes," he wrote, "the scripture declareth that women and children must perish with their parents . . . We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings." Mason, like most of the English commentators of the era, framed the conflict in terms of savagery and civilization; the "civilized" Protestants of the English empire were asserting their natural authority over "savage," pagan, and dark-skinned Indians. As the last fires at Mystic burned out, news of the tragedy spread throughout New England. A new and terrible era had begun.

***

The battle at Mystic had its roots in the initial contact in the early seventeenth century between English settlers and native peoples living in New England. The Pilgrims, who arrived in 1620, had the good fortune of encountering Squanto, a Wampanoag who helped the Pilgrims adjust to their new world. Within a few years, however, relations between the Pilgrims and local tribes soured. No matter how friendly the initial contact, it could not alter the English view of natives as untrustworthy savages. Indians, preached Anglican bishop John Jewell, were "a wild and naked people" who lived "without any civil government, offering up men's bodies in sacrifice, drinking men's blood . . . sacrificing boys and girls to certain familiar devils." Over the next few years the settlers stole native crops and acquired their land. In 1622, a militia captain killed eight friendly Indians, impaling the head of the sachem on top of the fort at Plymouth as a clear signal of their power. The Indians had a word for the white settlers: wotowquenange, which meant stabbers or cutthroats.

Both sides were already deeply suspicious of each other by the time Jonathan Winthrop and the six hundred Puritan settlers arrived on the shores of Massachusetts in June 1630. Unlike the mostly male crews of fortune seekers and laborers that landed in Virginia more than a decade earlier, the Puritans who founded the Plymouth Colony came as families--husbands, wives, children, and servants--seeking to locate permanently. They came to America determined to create a "Citty on the Hill," a utopia where individuals would work in common struggle to serve God's will. Winthrop wanted to escape a decadent England, with its Catholic queen, beggars, horse thieves, and "wandering ghosts in the shape of men." The Puritan mission was to tame the wilderness so their commonwealth would "shine like a beacon" back to immoral England.

The Puritan families wanted land and access to all of the bounties that the New World had to offer--a goal that put them in competition with the Indians for local natural resources. Most Puritans viewed Indians as dangerous, temporary obstacles to permanent English settlement in New England, not potential partners in the development of a new society. "The principall ende of this plantacion," their charter stated, was to "wynn and incite the natives of [the] country, to the knowledg and obedience of the onlie true God and Savior of mankinde, and the Christian fayth."

The Puritans came to America prepared to use force to achieve their ends. The Massachusetts Charter instructed settlers "to encounter, expulse, repel, and resist by force of arms" any effort to destroy the settlement. The settlers who arrived in Massachusetts aboard the Arabella were told to "neglect not walls, and bulwarks, and fortifications for your own defence." They brought with them five artillery pieces, skilled artisans who could make weapons, and a handful of professional soldiers. Shortly after arriving they set up a militia company. All males between the ages of sixteen and sixty were expected to serve.

Within the first three years as many as three thousand English had settled in the colony. By 1638, the population had swelled to eleven thousand. As the colony grew, the Puritans laid claim to land owned by the Indians. As God's "chosen people," the Puritans felt entitled to the land occupied by native tribes, often using Scripture to justify the outright seizure of territory. The new land was an untamed wilderness and their job was to subdue it for the glory of their God. The Puritans also offered secular justifications for taking possession of the land. Winthrop created a legal concept called vacuum domicilium, which proposed that Indians had defendable rights only to lands that were under cultivation. "As for the Natives in New England, they inclose noe Land, neither have any setled habytation, nor any tame Cattle to improve the Land by," Winthrop reasoned. If they left Indians land "sufficient for their use, we may lawfully take the rest, there being more than enough for them and us."

The Puritans' most powerful weapons in seizing Indian land were neither laws nor guns, but microbes. Over the centuries, Europeans had been exposed to and, through a process of evolution, developed immunity to a host of viruses. Indians, isolated on a distant continent, had never been exposed to the deadly microbes and therefore had no immunity. Smallpox was the biggest killer, but syphilis and various respiratory diseases added to the death toll. Tens of thousands of Indians died in the first year after the arrival of the English. By some estimates, disease killed 75 percent of the tribes in southern New England in less than two years. An Englishman wrote that the Indians had "died on heapes, as they lay in their houses, and the living that were able to shift for themselves wouyle runne away and let them dy, and let there Carkases ly above the ground without buriall."

As more Puritans disembarked in America, their settlements expanded farther west and south, eventually bringing them into contact with the Pequot. There were roughly thirteen thousand Pequots occupying the two thousand square miles of territory between the Niantic River in Connecticut and the Wecapaug River in Rhode Island. Little is known about the Pequot before their contact with Europeans. One historian described them as the "most numerous, the most warlike, the fiercest and the bravest of all aboriginal clans of Connecticut." Like other native tribes in southern New England, they depended on farming, hunting, and fishing for survival. The main difference between them and other nearby tribes, such as the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and Mattabesic, was that the Pequot built fortified villages. By 1637 they had constructed two large fortified hilltop villages--at Weinshauks and Mystic. In addition to these forts, they built smaller villages nearby containing as many as thirty wigwams, which were surrounded by a few hundred acres of cultivated land.

Highly organized with a powerful grand sachem and tribal council, the Pequot managed to establish military dominance over the other tribes in New England. In an effort to monopolize trade with early Dutch explorers, the Pequot subjugated nearby tribes. By the 1630s, the Pequot were the dominant political and military force in the area. Not only had they established extensive trading networks throughout the region, but they also occupied some of the region's most fertile soil.

Just as the English were planning to expand into Pequot territory, the tribe was decimated by disease. By 1634, the tribe that had numbered thirteen thousand a few years earlier now had only three thousand. John White, a planter in New England, wrote that "the Contagion hath scarce left alive one person of an hundred." Whole Indian tribes were decimated--too sick to hunt, fetch wood for fire, or take care of one another. Their bodies were full of bursting pox boils; "their skin cleaving by reason thereof to the mats they lie on. When they turn them, a whole side will flay off at once, and they will be all of a gore blood, most fearful to behold." The Puritans believed that the epidemics were gifts from God. "If God were not pleased with our inheriting these parts," Puritan Jonathan Winthrop wondered, "why did he drive out the natives before us? And why doth he still make room for us, by diminishing them as we increase?"

The once powerful Pequot found themselves under assault from all directions. Not only were they reeling from disease, they faced new economic competition. The Pequot occupied land that was rich in wampum--small sea shells drilled and strung together into beads. Until the arrival of the Europeans, wampum had served as a medium of exchange and communication for many tribes. They used it to create the insignia of sachems, command the service of shamans, console the bereaved, celebrate marriages, end blood feuds, and seal treaties. The Dutch, and later the English, however, recognized the economic value of wampum and started using it as a form of currency. Initially, the Pequot benefited from a lucrative trading system that involved exchanging wampum and furs for European manufactured goods. Eventually, however, the English decided to make their own wampum. Using steel drills, they produced large quantities of wampum, driving down its value and undermining the source of the Pequot's economic power.

The Pequot were divided over how to respond to the new economic threat posed by the English. The sachem Sassacus, deeply distrustful of the English, called for building an alliance with the Dutch to try to repel the English. The sub-sachem Uncas, who had married Sassacus's daughter, opposed these efforts. Believing it was futile to resist the more numerous and well-armed English, he advocated cooperation. (Uncas would be forever remembered as the fictionalized character in James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans.) The debate between these two powerful men ripped the tribe apart at a critical moment. After a series of heated debates, the tribal council sided with Sassacus and forced Uncas to leave the village. An angry Uncas formed a separate tribe, the Mohegan, and joined forces with the English in an effort to destroy his former tribe. Decimated by disease and torn apart by rival factions, the Pequot had never been more vulnerable.

The English moved quickly to take advantage of the opportunity. The immediate cause of the horrific attack on Mystic was revenge for the deaths of two Englishmen. In 1634, Captain John Stone, an English merchant, and his crew were found dead on their ship on the Connecticut River. Stone fell far short of the God-fearing ideal for an Englishman of the times. He was a notorious drunk, cheat, and liar. At the time of his death he was in trouble for stealing a ship full of Dutch trade goods from the Dutch governor of New York after a night of hard drinking. (Stone got the governor drunk as a diversionary tactic.) Informants from the Narragansett told colonial authorities that the Pequot ruthlessly murdered Stone and his men in their sleep. The Pequot told a different story. They claimed that Stone had taken two Indians captive. When Stone refused to release them, they took the ship by force. "This was related with such confidence and gravity," Winthrop said, "as having no means to contradict it, we inclined to believe it."

Descriere

This tie-in to The History Channel's ten-hour documentary series of the same name chronicles ten of the most influential and important events in America's past.