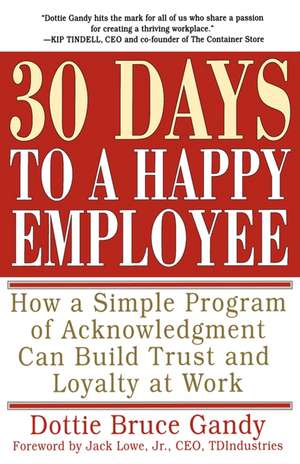

30 Days to a Happy Employee: How a Simple Program of Acknowledgment Can Build Trust and Loyalty at Work

Autor Dottie Gandyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 iun 2001

- A strong sense of loyalty and commitment among employees

- A new corporate culture built on a foundation of trust and designed to weather storms

- A renewed sense of mission that can have a substantial impact on the bottom line

Preț: 86.07 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 129

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.47€ • 17.17$ • 13.69£

16.47€ • 17.17$ • 13.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-14 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780684873299

ISBN-10: 068487329X

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

ISBN-10: 068487329X

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Notă biografică

Dottie Bruce Gandy, a business executive and entrepreneur who established two successful consulting practices, has focused throughout her career on helping organizations retain employees by winning their trust and loyalty. She directed a Texas-based regional office for the Franklin Covey Company. She and her husband, Tom, live in Allen, Texas.

Extras

Chapter OneBeyond the Paycheck...for a Reason

Everyone has an invisible sign hanging from their neck saying "Make me feel important."

?Mary Kay Ash

Charles Plumb, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was a jet pilot during the Vietnam War. After seventy-five combat missions, his plane was destroyed by a surface-to-air missile. Plumb safely ejected and parachuted into enemy territory. He was captured and spent six years in a Communist Vietnamese prison. He survived the ordeal and now lectures on the lessons he learned from that experience.

One day, when Plumb and his wife were sitting in a restaurant, a man at another table came up and said, "You're Plumb! You flew jet fighters in Vietnam from the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk. You were shot down!"

Somewhat surprised, Plumb asked, "How in the world did you know that?"

The man replied, "I packed your parachute."

Plumb gasped in surprise and gratitude. The man pumped his hand and said, "I guess it worked."

"It sure did. If the chute you packed hadn't worked, I wouldn't be here today," Plumb responded.

Plumb couldn't sleep that night, thinking about that man. He says, "I kept wondering what he might have looked like in a navy uniform: a white hat, a bib in the back, and bell-bottom trousers. I wonder how many times I might have seen him and not even said good morning, how are you, or anything else, because, you see, I was a fighter pilot, and he was just a sailor."

Now Plumb asks his audiences, "Who's packing your parachute?"

Plumb's story is a compelling reminder that our lives are richer and our work easier because of those who are committed to doing what is asked of them and doing it well. Surely they are worthy of our recognition.

Experts of all kinds have told us for years that next to physical survival, one of our deepest needs as human beings is to be affirmed or validated for who we are and what we contribute.

Nowhere is this more dramatically demonstrated than in the workplace. For at least the last twenty-five years, business surveys have reminded us that one of the main reasons employees voluntarily leave their jobs is that they do not feel valued for their contributions in human terms. Robert Half International Inc., for example, reports that as many as 25 percent of good employees who quit their jobs cite a lack of appreciation as their reason. With the average national job turnover at 2.7 million a year, thanks in part to the lure of start-up companies, the problem is approaching a near-crisis level.

In 1999, when Inc. magazine announced its annual list of the five hundred fastest-growing companies in the nation, 47 percent of those named said that not being able to attract and keep qualified employees was their number one inhibitor to growth.

The conclusion to be drawn is fairly simple: Employees who feel acknowledged for who they are and what they contribute tend to stay with their organizations. Those who don't, leave.

While some of those who leave say they are doing so for more money or a more impressive title, it takes little probing to realize that what many of them are really telling us is "Maybe if I earn more money or have a fancier title, I will feel more valued." They arrive at their new jobs full of hope. However, absent a culture that provides some authentic validation of who they are and what they contribute, their frustration surfaces all over again, and for many the job search resumes.

The irony of this chase for recognition is that employees have come to accept the fact that they will probably spend their working years being underacknowledged and underappreciated. They learn to settle for a work environment that asks much and gives back much less. That such an approach is costly to employers seems to be incidental to avoiding the challenge of taking the (inexpensive) time to let the people they count on the most know just that.

From my perspective, it seems almost insane to think that businesses would spend more and more of their budget dollars on expensive reward and recognition programs that get a much lower return on employee productivity than they would to institute a culture where individuals are routinely honored and productivity soars. This alone argues for a new approach.

What seems to be missing is the kind of acknowledgment that inspires employees to perform at extraordinary levels; that engenders the kind of loyalty that ensures rather than impedes growth; that results in a corporate culture founded on respect for the individual.

Even the enlightened workplaces that recognize the need to provide such a culture seem to flounder when it comes to implementation. At best they look for more and more ways to honor employees through elaborate reward and recognition programs, heaping expensive gifts and extravagant travel on the few who are fortunate enough to be singled out for honor. What they fail to do, however, is let their employees know, across the board and on a day-to-day basis, that who they are matters and what they contribute makes a difference.

I'm talking about the simplicity of saying something like "I know we ask a lot of you, and I can't see that changing. What I want you to know, however, is how much we appreciate who you are and your willingness to show up every day and do your job well." Over and over again while I was collecting data for this book, employees said they would happily trade the occasional gift/trip for a job done well for a sincere, repeated pat on the back that would let them know their efforts are appreciated.

One employee who voluntarily left his position with a well-known nonprofit organization because he didn't feel his efforts were acknowledged said, "I would have stayed for a smile."

This book offers a unique 30-Day Process that responds to our desire to provide the kind of acknowledgment that gives us what we seek from those who matter most?a reminder that we are intrinsically good people worthy of such appreciation. Specifically, the 30-Day Process extends an invitation to see the contributions and qualities of others in a way that we have never done, one that goes beyond the obvious to the intrinsic.

This is not a book about reward and recognition. This is a book about acknowledgment. The distinction lies in the outcome. If what you are seeking is short-term, temporary loyalty, reward and recognition programs will suffice. If you are looking for long-term sustainable improvement in workplace performance and retention, acknowledgment is the key.

The 30-Day Process explained later in this book invites us to share, face-to-face, a different quality or trait that we admire and appreciate about another person?every day for thirty days. (For those of you who blanch at the thought of promising to do anything for thirty days, hang on until you know the rest of the story.)

Along with the process, this book makes a strong case for what happens when such acknowledgment is provided on an ongoing basis, as well as what happens when acknowledgment is withheld or used inappropriately.

While the 30-Day Process will create happier and more productive employees, it is actually the means to a much larger end, a new outlook for the manager/company that fosters an atmosphere in which everyone thrives. The process quickly becomes self-affirming when it is understood that we cannot see in another that which does not already exist in us. In other words, the resulting exhilaration is felt as much by the one giving the compliments as by the one receiving them.

This book also explores the domino effect that occurs: one person, appropriately acknowledged, tends to pass the acknowledgment on, almost unconsciously, until one day the organization's employees look around and notice that something is very different. The process teaches us to think differently about the people we employ, just as Charles Plumb now thinks differently about those who packed his parachutes. In other words, the 30-Day Process, initially an end in itself, becomes the tail that wags the dog in its capacity to transform the workplace by elevating acknowledgment from a random act of appreciation to a sustained, intentional way of being.

Chapters 12 to 14 of this book profile three very different organizations that have "gotten it" with respect to the kind of acknowledgment I'm talking about. These companies understand the difference between workplace appreciation that is a come from rather than a how-to.

The idea for the 30-Day Process surfaced during a performance review in 1996. At the time I was directing the Dallas office of the Franklin Covey Company. For a long time, I have been significantly influenced by the teachings of Dr. Stephen R. Covey in his international best-seller, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Of particular value to me has been his concept of "making deposits into the emotional bank account" of another person as a way of building trust in a relationship. Since traditional performance reviews have hardly been thought of as a way to build trust, I wondered if there was a way to blend these two ideas.

Thus, in 1996, when it was time to conduct a performance review with one of my staff, I suggested the nontraditional approach of asking if, over the course of the next thirty days, I could share with that person different things I admired and appreciated about her (which, I hoped, would be viewed as deposits into her emotional bank account). The results, as you will hear more about in the next chapter, were phenomenal.

I then tried the same process with large numbers of individuals, both inside and outside the workplace. The results were similarly impressive.

Eventually, I elected to resign my position with the Franklin Covey Company to devote myself full-time to researching and writing about what happens when organizations (and individuals) take on the task of acknowledgment in a way that produces extraordinary results.

I conducted workshops with a variety of companies to determine the outcome when people feel fully valued for their contributions. This book will expand on those results. I will examine the consequences of offering -- and withholding -- the kind of workplace validation we so richly deserve and desire.

In the chapters that follow, I share the significant results of what happens when individuals reconnect with their own goodness by helping another connect with his or her intrinsic qualities. I share stories about the long-term, sustainable transformation that occurs when individuals are affirmed and validated, when their gifts and skills are revealed and celebrated.

According to Merriam-Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary, one definition of acknowledgment is an "admission of the truth...about our true character." Thus, I am writing about the kind of acknowledgment for which most of us yearn but rarely get, that which validates our "true character." Specifically, I want to encourage each of us to do a better job -- for some of us a much better job -- of letting the people around us know how much we appreciate the qualities, skills, and competencies that make life and work a little better.

It is my hope that this book will become an indispensable tool for "breaking the good news" about ourselves.

Copyright © 2001 by Dottie Bruce Gandy

Everyone has an invisible sign hanging from their neck saying "Make me feel important."

?Mary Kay Ash

Charles Plumb, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was a jet pilot during the Vietnam War. After seventy-five combat missions, his plane was destroyed by a surface-to-air missile. Plumb safely ejected and parachuted into enemy territory. He was captured and spent six years in a Communist Vietnamese prison. He survived the ordeal and now lectures on the lessons he learned from that experience.

One day, when Plumb and his wife were sitting in a restaurant, a man at another table came up and said, "You're Plumb! You flew jet fighters in Vietnam from the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk. You were shot down!"

Somewhat surprised, Plumb asked, "How in the world did you know that?"

The man replied, "I packed your parachute."

Plumb gasped in surprise and gratitude. The man pumped his hand and said, "I guess it worked."

"It sure did. If the chute you packed hadn't worked, I wouldn't be here today," Plumb responded.

Plumb couldn't sleep that night, thinking about that man. He says, "I kept wondering what he might have looked like in a navy uniform: a white hat, a bib in the back, and bell-bottom trousers. I wonder how many times I might have seen him and not even said good morning, how are you, or anything else, because, you see, I was a fighter pilot, and he was just a sailor."

Now Plumb asks his audiences, "Who's packing your parachute?"

Plumb's story is a compelling reminder that our lives are richer and our work easier because of those who are committed to doing what is asked of them and doing it well. Surely they are worthy of our recognition.

Experts of all kinds have told us for years that next to physical survival, one of our deepest needs as human beings is to be affirmed or validated for who we are and what we contribute.

Nowhere is this more dramatically demonstrated than in the workplace. For at least the last twenty-five years, business surveys have reminded us that one of the main reasons employees voluntarily leave their jobs is that they do not feel valued for their contributions in human terms. Robert Half International Inc., for example, reports that as many as 25 percent of good employees who quit their jobs cite a lack of appreciation as their reason. With the average national job turnover at 2.7 million a year, thanks in part to the lure of start-up companies, the problem is approaching a near-crisis level.

In 1999, when Inc. magazine announced its annual list of the five hundred fastest-growing companies in the nation, 47 percent of those named said that not being able to attract and keep qualified employees was their number one inhibitor to growth.

The conclusion to be drawn is fairly simple: Employees who feel acknowledged for who they are and what they contribute tend to stay with their organizations. Those who don't, leave.

While some of those who leave say they are doing so for more money or a more impressive title, it takes little probing to realize that what many of them are really telling us is "Maybe if I earn more money or have a fancier title, I will feel more valued." They arrive at their new jobs full of hope. However, absent a culture that provides some authentic validation of who they are and what they contribute, their frustration surfaces all over again, and for many the job search resumes.

The irony of this chase for recognition is that employees have come to accept the fact that they will probably spend their working years being underacknowledged and underappreciated. They learn to settle for a work environment that asks much and gives back much less. That such an approach is costly to employers seems to be incidental to avoiding the challenge of taking the (inexpensive) time to let the people they count on the most know just that.

From my perspective, it seems almost insane to think that businesses would spend more and more of their budget dollars on expensive reward and recognition programs that get a much lower return on employee productivity than they would to institute a culture where individuals are routinely honored and productivity soars. This alone argues for a new approach.

What seems to be missing is the kind of acknowledgment that inspires employees to perform at extraordinary levels; that engenders the kind of loyalty that ensures rather than impedes growth; that results in a corporate culture founded on respect for the individual.

Even the enlightened workplaces that recognize the need to provide such a culture seem to flounder when it comes to implementation. At best they look for more and more ways to honor employees through elaborate reward and recognition programs, heaping expensive gifts and extravagant travel on the few who are fortunate enough to be singled out for honor. What they fail to do, however, is let their employees know, across the board and on a day-to-day basis, that who they are matters and what they contribute makes a difference.

I'm talking about the simplicity of saying something like "I know we ask a lot of you, and I can't see that changing. What I want you to know, however, is how much we appreciate who you are and your willingness to show up every day and do your job well." Over and over again while I was collecting data for this book, employees said they would happily trade the occasional gift/trip for a job done well for a sincere, repeated pat on the back that would let them know their efforts are appreciated.

One employee who voluntarily left his position with a well-known nonprofit organization because he didn't feel his efforts were acknowledged said, "I would have stayed for a smile."

This book offers a unique 30-Day Process that responds to our desire to provide the kind of acknowledgment that gives us what we seek from those who matter most?a reminder that we are intrinsically good people worthy of such appreciation. Specifically, the 30-Day Process extends an invitation to see the contributions and qualities of others in a way that we have never done, one that goes beyond the obvious to the intrinsic.

This is not a book about reward and recognition. This is a book about acknowledgment. The distinction lies in the outcome. If what you are seeking is short-term, temporary loyalty, reward and recognition programs will suffice. If you are looking for long-term sustainable improvement in workplace performance and retention, acknowledgment is the key.

The 30-Day Process explained later in this book invites us to share, face-to-face, a different quality or trait that we admire and appreciate about another person?every day for thirty days. (For those of you who blanch at the thought of promising to do anything for thirty days, hang on until you know the rest of the story.)

Along with the process, this book makes a strong case for what happens when such acknowledgment is provided on an ongoing basis, as well as what happens when acknowledgment is withheld or used inappropriately.

While the 30-Day Process will create happier and more productive employees, it is actually the means to a much larger end, a new outlook for the manager/company that fosters an atmosphere in which everyone thrives. The process quickly becomes self-affirming when it is understood that we cannot see in another that which does not already exist in us. In other words, the resulting exhilaration is felt as much by the one giving the compliments as by the one receiving them.

This book also explores the domino effect that occurs: one person, appropriately acknowledged, tends to pass the acknowledgment on, almost unconsciously, until one day the organization's employees look around and notice that something is very different. The process teaches us to think differently about the people we employ, just as Charles Plumb now thinks differently about those who packed his parachutes. In other words, the 30-Day Process, initially an end in itself, becomes the tail that wags the dog in its capacity to transform the workplace by elevating acknowledgment from a random act of appreciation to a sustained, intentional way of being.

Chapters 12 to 14 of this book profile three very different organizations that have "gotten it" with respect to the kind of acknowledgment I'm talking about. These companies understand the difference between workplace appreciation that is a come from rather than a how-to.

The idea for the 30-Day Process surfaced during a performance review in 1996. At the time I was directing the Dallas office of the Franklin Covey Company. For a long time, I have been significantly influenced by the teachings of Dr. Stephen R. Covey in his international best-seller, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Of particular value to me has been his concept of "making deposits into the emotional bank account" of another person as a way of building trust in a relationship. Since traditional performance reviews have hardly been thought of as a way to build trust, I wondered if there was a way to blend these two ideas.

Thus, in 1996, when it was time to conduct a performance review with one of my staff, I suggested the nontraditional approach of asking if, over the course of the next thirty days, I could share with that person different things I admired and appreciated about her (which, I hoped, would be viewed as deposits into her emotional bank account). The results, as you will hear more about in the next chapter, were phenomenal.

I then tried the same process with large numbers of individuals, both inside and outside the workplace. The results were similarly impressive.

Eventually, I elected to resign my position with the Franklin Covey Company to devote myself full-time to researching and writing about what happens when organizations (and individuals) take on the task of acknowledgment in a way that produces extraordinary results.

I conducted workshops with a variety of companies to determine the outcome when people feel fully valued for their contributions. This book will expand on those results. I will examine the consequences of offering -- and withholding -- the kind of workplace validation we so richly deserve and desire.

In the chapters that follow, I share the significant results of what happens when individuals reconnect with their own goodness by helping another connect with his or her intrinsic qualities. I share stories about the long-term, sustainable transformation that occurs when individuals are affirmed and validated, when their gifts and skills are revealed and celebrated.

According to Merriam-Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary, one definition of acknowledgment is an "admission of the truth...about our true character." Thus, I am writing about the kind of acknowledgment for which most of us yearn but rarely get, that which validates our "true character." Specifically, I want to encourage each of us to do a better job -- for some of us a much better job -- of letting the people around us know how much we appreciate the qualities, skills, and competencies that make life and work a little better.

It is my hope that this book will become an indispensable tool for "breaking the good news" about ourselves.

Copyright © 2001 by Dottie Bruce Gandy

Cuprins

Contents

Author?s Note

FOREWORD by Jack Lowe, Jr.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

Chapter One

Beyond the Paycheck...for a Reason

Chapter Two

Once Upon a Performance Review

Chapter Three

The High Cost of Low Trust

Chapter Four

A Thirty-Day Journey That Lasts a Lifetime

Chapter Five

The 30-Day Process: Motivation or Manipulation?

Chapter Six

Putting Down Stakes Where It Matters

Chapter Seven

It Takes One to Know One

Chapter Eight

The Acknowledgment Domino Effect

Chapter Nine

Even More Ways to Celebrate You

Chapter Ten

(Ap)praising Performance

Chapter Eleven

Sometimes the Best Place to Begin Is at Home

Chapter Twelve

The "Lowe" Down on TDIndustries

Chapter Thirteen

The Best Place to Get Organized Is Also the Best Place to Work

Chapter Fourteen

Living and Working in a State of "Grace"

Chapter Fifteen

Now What?

APPENDIX I

A Summary of the 30-Day Process Guidelines

APPENDIX II

Frequently Cited Traits

APPENDIX III

A Sample List of Thirty Traits

Recenzii

Kip Kindell CEO and co-founder of The Container Store Dottie Gandy hits the mark for all of us who share a passion for creating a thriving workplace.

Dr. Stephen R. Covey bestselling author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Dottie's 30-Day Process is as useful in transforming workplace quality as it is in strengthening the family.

Dr. Stephen R. Covey bestselling author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Dottie's 30-Day Process is as useful in transforming workplace quality as it is in strengthening the family.