A Blessed Child: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream

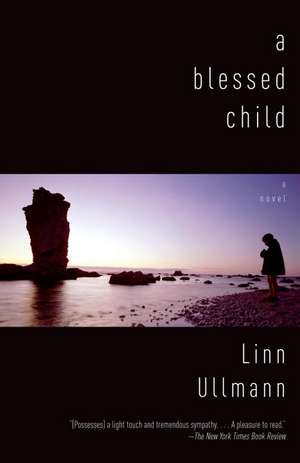

Autor Linn Ullmannen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

Every summer Isak Lövenstad gathers his three daughters by different wives to the windswept Baltic island of Hammarsö. Here Erika, Laura, and Molly find a sense of family and friendship, although nothing can match Erika's connection to the rebellious misfit Ragnar. But when an act of senseless cruelty separates them forever—and drives the sisters from the island in shame and regret—they must leave childhood and their growing relationships behind. Now, twenty-five years later, they return to visit their ailing father and confront the specter of that awful summer.

Preț: 102.40 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 154

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.59€ • 20.21$ • 16.35£

19.59€ • 20.21$ • 16.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 05-19 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307277817

ISBN-10: 030727781X

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 030727781X

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Linn Ullmann is a graduate of New York University, where she studied English literature and began work on a Ph.D. She returned to her native Oslo in 1990 to pursue a career in journalism. A prominent literary critic, she also writes a column for Norway's leading morning newspaper. She lives in Oslo.

Extras

I

The Road

In the winter of 2005, Erika went to see her father, Isak Lövenstad. The journey was taking longer than expected, and she felt a strong urge to turn around and drive back to Oslo, but she pressed on, keeping her mobile phone on the seat beside her so she could ring him at any time and say that the visit was off. That she wasn’t coming after all. That they would have to do it another time. She could say it was because of the weather, the heavy snowfall. The change of plan would have been a great relief to both of them.

Isak was eighty-four years old and lived by himself in a white limestone house on Hammarsö, an island off the east coast of Sweden. A specialist in gynecology, he had made his name as one of the pioneers of ultrasound. Now in retirement, he was in good health and his days passed pleasantly. All his basic needs were met by Simona, a lifelong resident of the island. Simona saw to it that he had a hot lunch and dinner every day; she gave the house a thorough weekly cleaning; she shopped, dusted, and did his laundry, of which there was not much. She also helped him with his annual income tax return and payments. Isak still had all his teeth, but in the past year he had developed a cataract in his right eye. He said it was like looking at the world through water.

Isak and Simona rarely talked to each other. Both preferred it that way.

After a long, full life in Stockholm and Lund, Isak had moved to Hammarsö for good. The house had stood empty for twelve years, during which time he had more than once considered selling it. Instead he decided to sell his flats in Stockholm and Lund and spend the rest of his life as an islander. Simona, whom Isak had hired back in the early seventies to help Rosa take care of the house (in spite of knowing that Rosa was the kind of woman, quite different from his previous wife and mistresses, who rarely needed help with anything, and especially not with the house, which by Rosa was kept to perfection), insisted that he allow her to take him in hand and cut his hair regularly. He wanted to leave it to grow. There was no one to cut it for, he said, but in order to restore the mutually preferred silence between them, they reached a compromise. In summer, the crown of Isak’s head was blank and glossy and as blue as the globes he had presented to each of his three daughters, Erika, Laura, and Molly, on her fifth birthday; in the winter, he let his hair grow free, giving him an aspect of towering grayish white, which in combination with his handsomely lined, aging face suggested the beginnings of a rauk, one of those four-hundered-million-year-old island outcrops in the sea, so characteristic of Hammarsö.

Erika seldom saw her father after he had moved to the island, but Simona had sent her two photographs. One of a long-haired Isak and one of the almost bald Isak. Erika liked the long-haired one better. She ran her finger over the picture and kissed it. She imagined him on the stony beach on Hammarsö with arms stretched aloft, hair streaming out, and that long, fake beard he would wear when rehearsing his lines as Wise Old Man for the 1979 Hammarsö Pageant.

Rosa—Isak’s second wife and Laura’s mother—died of a degenerative muscle-wasting disease in the early 1990s. It was Rosa’s death that prompted Isak’s return to Hammarsö. In the twelve years the house had stood empty, there had been only occasional visits from Simona. She had swept up the insect life that forced its way in every summer and lay dead on the windowsills all winter; she had the locks changed after a minor break-in and mopped up when the pipes burst and water leaked all over the floor. But she could do nothing about the water damage and rot if Isak was not prepared to pay for workmen to come in and fix them.

“It’s going to get run-down whatever I do,” she said in one of their brief telephone conversations. “You’ll either have to sell it, do it up, or start living in it again.”

“Not yet. I’m not making any decisions yet,” Isak said.

But then Rosa’s body let her down, and though her heart was strong and wouldn’t stop beating, Isak and a colleague agreed in the end that Rosa should be spared. After the funeral, Isak made it plain to Erika, Laura, and Molly that he intended to kill himself. The pills had been procured, the deed carefully planned. And yet, he moved back to the house.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Road

In the winter of 2005, Erika went to see her father, Isak Lövenstad. The journey was taking longer than expected, and she felt a strong urge to turn around and drive back to Oslo, but she pressed on, keeping her mobile phone on the seat beside her so she could ring him at any time and say that the visit was off. That she wasn’t coming after all. That they would have to do it another time. She could say it was because of the weather, the heavy snowfall. The change of plan would have been a great relief to both of them.

Isak was eighty-four years old and lived by himself in a white limestone house on Hammarsö, an island off the east coast of Sweden. A specialist in gynecology, he had made his name as one of the pioneers of ultrasound. Now in retirement, he was in good health and his days passed pleasantly. All his basic needs were met by Simona, a lifelong resident of the island. Simona saw to it that he had a hot lunch and dinner every day; she gave the house a thorough weekly cleaning; she shopped, dusted, and did his laundry, of which there was not much. She also helped him with his annual income tax return and payments. Isak still had all his teeth, but in the past year he had developed a cataract in his right eye. He said it was like looking at the world through water.

Isak and Simona rarely talked to each other. Both preferred it that way.

After a long, full life in Stockholm and Lund, Isak had moved to Hammarsö for good. The house had stood empty for twelve years, during which time he had more than once considered selling it. Instead he decided to sell his flats in Stockholm and Lund and spend the rest of his life as an islander. Simona, whom Isak had hired back in the early seventies to help Rosa take care of the house (in spite of knowing that Rosa was the kind of woman, quite different from his previous wife and mistresses, who rarely needed help with anything, and especially not with the house, which by Rosa was kept to perfection), insisted that he allow her to take him in hand and cut his hair regularly. He wanted to leave it to grow. There was no one to cut it for, he said, but in order to restore the mutually preferred silence between them, they reached a compromise. In summer, the crown of Isak’s head was blank and glossy and as blue as the globes he had presented to each of his three daughters, Erika, Laura, and Molly, on her fifth birthday; in the winter, he let his hair grow free, giving him an aspect of towering grayish white, which in combination with his handsomely lined, aging face suggested the beginnings of a rauk, one of those four-hundered-million-year-old island outcrops in the sea, so characteristic of Hammarsö.

Erika seldom saw her father after he had moved to the island, but Simona had sent her two photographs. One of a long-haired Isak and one of the almost bald Isak. Erika liked the long-haired one better. She ran her finger over the picture and kissed it. She imagined him on the stony beach on Hammarsö with arms stretched aloft, hair streaming out, and that long, fake beard he would wear when rehearsing his lines as Wise Old Man for the 1979 Hammarsö Pageant.

Rosa—Isak’s second wife and Laura’s mother—died of a degenerative muscle-wasting disease in the early 1990s. It was Rosa’s death that prompted Isak’s return to Hammarsö. In the twelve years the house had stood empty, there had been only occasional visits from Simona. She had swept up the insect life that forced its way in every summer and lay dead on the windowsills all winter; she had the locks changed after a minor break-in and mopped up when the pipes burst and water leaked all over the floor. But she could do nothing about the water damage and rot if Isak was not prepared to pay for workmen to come in and fix them.

“It’s going to get run-down whatever I do,” she said in one of their brief telephone conversations. “You’ll either have to sell it, do it up, or start living in it again.”

“Not yet. I’m not making any decisions yet,” Isak said.

But then Rosa’s body let her down, and though her heart was strong and wouldn’t stop beating, Isak and a colleague agreed in the end that Rosa should be spared. After the funeral, Isak made it plain to Erika, Laura, and Molly that he intended to kill himself. The pills had been procured, the deed carefully planned. And yet, he moved back to the house.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Ullmann's sentences...are a pleasure to read and her deft modern sensibility is winning.”—The New York Times Book Review“Linn Ullmann's A Blessed Child is a like a fine, long evening of light. There are all sorts of colors on the horizon, and even when the darkness becomes visible, there is still a place to turn to. This is a book for fathers and daughters, and for anyone who's beguiled by the country of family. The language is clear and runs deep. The story is profound and touching. Together, they announce another great story telling feat by Linn Ullmann. She reminds me of Berger, of Aciman, of Toibin: no greater praise.”—Colum McCann, author of Zoli: A Novel“A world-famous octogenarian father approaching death, three daughters, each of a different mother, a windswept island in the Baltic: of these, of fragments of recollection, and of a childhood summer when an event of unimaginable cruelty changed everything, Linn Ullmann has woven a memory novel of haunting power and grace."—Honor Moore, author of The Bishop's Daughter“A hauntingly beautiful novel of family ties, A Blessed Child takes on what it means to be old, what it means to have loved selfishly, deeply and - equally - to no longer love. Linn Ullmann has crafted an inescapably evocative novel about memory, about childhood, about the movement of life, the nature of grief and the enormous mystery of love.”—A.M. Homes, author of The Mistress's Daughter“A Blessed Child is a tour de force of, for want of a better way of putting it, narrative memory. In this nuanced and subtle and smart novel, the past and its tragedies are supervening over the present and its tragedies in wait, and even the living can seem to inhabit a kind of timeless island of familial memory. The folding of time upon time upon time, however complexly difficult for the writer to achieve, creates an effect that is sure and beautiful. This is a novel about how people think, and about the things we think, and about how, finally, the manner and content of our thoughts may very well be pretty much who we are.”—Donald Antrim, author of The Afterlife: A Memoir"A novel of stark beauty that leaves moral issues tantalizingly open."—Kirkus Reviews