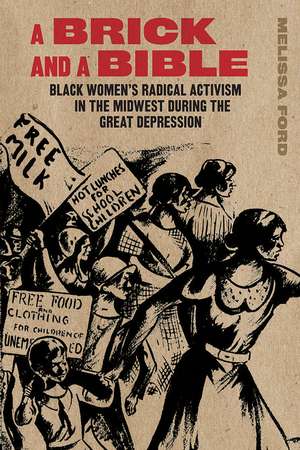

A Brick and a Bible: Black Women's Radical Activism in the Midwest during the Great Depression

Autor Melissa Forden Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 apr 2022

Uncovering the social revolution led by Black women in the heartland

In this first study of Black radicalism in midwestern cities before the civil rights movement, Melissa Ford connects the activism of Black women who championed justice during the Great Depression to those involved in the Ferguson Uprising and the Black Lives Matter movement. A Brick and a Bible examines how African American working-class women, many of whom had just migrated to “the promised land” only to find hunger, cold, and unemployment, forged a region of revolutionary potential.

A Brick and a Bible theorizes a tradition of Midwestern Black radicalism, a praxis-based ideology informed by but divergent from American Communism. Midwestern Black radicalism that contests that interlocking systems of oppression directly relates the distinct racial, political, geographic, economic, and gendered characteristics that make up the American heartland. This volume illustrates how, at the risk of their careers, their reputations, and even their lives, African American working-class women in the Midwest used their position to shape a unique form of social activism.

Case studies of Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Cleveland—hotbeds of radical activism—follow African American women across the Midwest as they participated in the Ford Hunger March, organized the Funsten Nut Pickers’ strike, led the Sopkin Dressmakers’ strike, and supported the Unemployed Councils and the Scottsboro Boys’ defense. Ford profoundly reimagines how we remember and interpret these “ordinary” women doing extraordinary things across the heartland. Once overlooked, their activism shaped a radical tradition in midwestern cities that continues to be seen in cities like Ferguson and Minneapolis today.

Preț: 266.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 399

Preț estimativ în valută:

50.91€ • 52.59$ • 42.37£

50.91€ • 52.59$ • 42.37£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809338559

ISBN-10: 0809338556

Pagini: 242

Ilustrații: 14

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809338556

Pagini: 242

Ilustrații: 14

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Melissa Ford is an assistant professor at Slippery Rock University specializing in African American history. Her work has appeared in American Communist History. She is a former Black Metropolis Research Consortium fellow.

Extras

Introduction: Midwestern Black Radicalism

For tens of thousands of African Americans living in the South in the first half of the twentieth century, the American heartland was the promised land. The urban Midwest spoke to ambitions and hopes of employment, free cultural expression, political rights, and racial equality. Cities like Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, and Chicago beckoned Black migrants from their homes in the South, representing a dream that could no longer be deferred. For one woman, only identified as a “Negro Woman Worker,” the Midwest embodied the American dream. She had moved to Cleveland from a “hell-hole town in Mississippi” to seek employment, a better standard of living, and relief from pervasive racism. Yet, she could not find work, she often went hungry, and she could not afford heat during the winter months. She wrote a letter to the national Communist journal The Working Woman in 1930 to express her frustrations. She asked, “Why don’t the government take care of us while there isn’t any work, so that we don’t have to freeze and starve?” Her frustration did not end at letter writing. She firmly declared she was “ready to fight,” and that “the club and pistol were made for the working class.” Her story does not have a conclusion; there are no more records of this remarkable woman who went out of her way to document and share her ordeal as a Southern migrant in a Midwestern city.

Though an individual story, the “Negro Woman Worker’s” experience paralleled that of thousands of other African American women in the early 1930s. These women, with dreams of racial equality and steady employment, flocked to Midwestern cities, but often found conditions not so different from those they escaped. However, as the letter writer from Cleveland demonstrated, the desperation of the Depression’s hardest-hit population did not indicate apathy or indifference; rather, many Black women during this period represented the fiercest champions of the working class. Due to sexist, racist, and classist systems of oppression, however, finding outlets for this radical activism was often a formidable challenge for these women. As the letter writer showed, though, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) offered avenues heretofore unheard of for Black working-class women in the Midwest.

African American women who participated in Communist-affiliated activities blended their personal and regional histories, their lived experiences, and their ideas of gender and racial equality with party doctrine in a way that established them as important radical activists during the Great Depression. Every individual woman approached her activism differently: Ida Carter bypassed her local church leaders on Chicago’s South Side and organized a strike in coordination with national Communist leaders, seeing it through to a successful conclusion. Carrie Smith stood in front of St. Louis’s City Hall and rallied her fellow workers out of complacency and fear into militant action. She hoisted a brick in one hand, a Bible in the other, and declared, “Girls, we cannot lose!” Mattie Woodson of Detroit officially joined the Communist Party and hosted clandestine meetings in her home, risking her life, job, and reputation. After an anti-eviction riot left her comrades dead, Maggie Jones in Cleveland organized a nurses’ brigade trained in first aid to avoid future tragedy. Thousands of other Black women in the Midwest faded in and out of the Communist Party, attending rallies and protests, but never officially joining the party or making the pages of Communist records. These “Negro Women Workers,” unnamed but no less essential in the struggle, incorporated their notions of race, class, gender, and region to exercise their interpretation of Black radicalism in the Midwest.

A Brick and a Bible documents how, in the span of a few years during the early Great Depression, thousands of African American women in the urban Midwest directly engaged with members of the CPUSA to fight unfair wages, substandard working conditions, and racial discrimination in the workplace as well as hunger, poverty, and homelessness in their communities. From Cleveland to St. Louis, from Chicago to Detroit, these women worked closely with the Communists, sometimes even joining the party, to achieve their short- and long-term goals. When examined through the lenses of gender, race, class, and region, the history of these women, Black radicalism, and the Communist Party in the early Great Depression takes on a new historical importance that challenges how we understand American racial and working-class history today. Because gender, race, class, and region are essential parts of this study, yet were not always central to the CPUSA’s activity, a new term must be realized for these women’s activism. Therefore, I offer Midwestern Black radicalism, formulated as a distinct expression of praxis-based Black radical ideology informed by American Communism, African American community-building, Black women’s history of resistance, and the lived experiences of Black women in the Midwest during the Great Depression. Midwestern Black radicalism directly relates to unique racial, political, geographic, economic, gendered, and spatial characteristics that make up the American heartland. These Black radicals both accepted and challenged the teachings of the CPUSA, while also creating something particular and unique. Midwestern Black radicalism refers to more than the location where these radical activists organized and agitated; rather this particular interpretation of Black radicalism is markedly shaped by many factors. Urban development, industrialization, patterns of migration and residency, and interactions of race, class, and gender in social spaces form the foundation for expressions of Midwestern Black radicalism; as well, individual stories make it come alive. And, most importantly, African American women are the heart of this overlooked radicalism in the heartland. As such, A Brick and a Bible and Midwestern Black radicalism interrogate the crossroads of African American history, gender studies, labor history, and Midwestern studies, calling for a profound re-imagining of how we remember and interpret these women’s stories.

The burden of defining the Midwest has kept regional historians busy for decades, and though it probably remains an impossible task, it deserves a brief mention. R. Douglas Hunt warns that scholars should not place too much emphasis on geographical boundaries, as they are a “mental construct.” Though climate, environment, geography, and location “set the parameters” for our regional understanding, the distinctiveness ultimately comes from a social and cultural understanding. This study posits the Midwest as a shared cultural and social space marked by distinctive characteristics of residential segregation, migratory patterns, dependence on Black labor, light and heavy industry, virulent racism, and expansion of radical interracial coalition building. This study focuses on four Midwestern cities: Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Cleveland, but the geographic understanding of the regional Midwest extends to Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, and Western Pennsylvania. It is a seemingly simple geographic region ranging from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians, north of the Ohio River and the Missouri Compromise border. It is known in the popular American imagination as the land of “amber waves of grain,” dairy farms, and conservative thinking. This region has never been known for its radicalism; in fact, in 1922 philosopher John Dewey observed that the Midwest “has been the middle in every sense of the word and in every movement.” The region operated as a stabilizing force, whose people “never had an interest in ideas as ideas, nor in science and art for what they may do in liberating and elevating the human spirit.” This popular notion of an ordinary space and region only covers for a deeply traumatic past. Historian Brent Campney argues that the Midwest’s claim to “pastoral meritocracy” was maintained through racial exclusion and bloodshed and documents a disturbing trend of violence, brutality, and lynchings in the region. In her work on the Black Midwest, Ashley Howard adds that “economic and race oppression acted as co-conspirators,” resulting in explosive conditions. Though she specifically addresses urban riots post-World War II, Howard’s observations on economics, race, and the Midwest are fitting for the first half of the twentieth century as well. The heartland is often synonymous with traditional white American values and politics, but the lived experiences of African Americans in the heartland, regardless of era, were marked by prejudice, violence, segregation, and struggle.

Economic potential brought migrants to Midwestern cities during the Great Migration, however prevailing racism limited economic opportunities. The influx of Black Southerners shaped the character of these cities in ways unparalleled in the Northeast. Midwestern cities were home to millions of people, thriving industries, vibrant cultural centers, robust political landscapes, and tumultuous race and class tensions. In 1930, the Midwest boasted four of the largest cities in the United States: Chicago (second, with 3.3 million people, 6.9 percent Black), Detroit (fourth, with 1.5 million, 7.7 percent Black), Cleveland (sixth, with 900,429, 7.9 percent Black), and St. Louis (seventh, with 821,960, 11.4 percent Black). While New York City certainly had a larger overall population and more African Americans called it home, the percentage of Blacks in the city in 1930 was only 4.73 percent, less than the percentage of Blacks in each of the ten most populated Midwestern cities. Out of the five boroughs, only Manhattan’s percentage was greater, with an African American population of 12 percent in 1930. While New York City has often received the most attention in terms of the numbers of Southern migrants, the drastic percentage increase of African Americans in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland significantly altered the economic, political, and social landscape in ways unseen in other urban areas.

Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis showed striking similarities in terms of industry, population, neighborhood arrangement, and politics, as this book documents. As Cedric Robinson argues, Black radicalism begins with tension, and racial tension was the defining feature during the 1920s and 30s for Midwestern cities. Therefore, Midwestern Black radicalism begins with the Great Migration and gains momentum with the Great Depression. Thousands of workers poured into Midwestern cities in pursuit of jobs and a less racist social order, however they faced substantial challenges. While Jim Crow did not have legal standing in cities like St. Louis or Cleveland, de facto segregation practices prevented equal opportunity for the cities’ newest residents. Unions habitually excluded Blacks from membership, restaurants and other public places still allowed segregated facilities, and discriminatory housing policies relegated working-class African Americans to the cities’ least desirable areas. From Chicago’s South Side to Cleveland’s Central Area, and from East St. Louis to Detroit’s Black Bottom, working-class Black Midwesterners experienced some of the worst living conditions urban areas had to offer. Lack of indoor plumbing, neglectful landlords, overcrowded apartments, and ramshackle buildings characterized many Black migrants’ new homes. Recent migrants to the urban Midwest found their situation a far cry from the “paradise” that Black newspapers advertised, and, while improved in many respects, Midwestern urban areas still resembled those in the South. Yet each Midwestern city stood on its own, as each experienced race, class, and gender relations differently. The stories set in each city reveal certain aspects of Midwestern Black radicalism, and while many of the themes overlap, each city was unique. Midwestern Black radicalism during the 1930s necessarily involved organizing at many levels, addressing local politics, changing strategic tactics, and incorporating themes of motherhood, community, religion, and local politics. As these women show, adaptability to the city and the historical conditions was key.

This study is in a part a reclamation effort, but it is by no means exhaustive on the subject of Midwestern Black radicalism. Some Midwestern cities, such as Milwaukee, had a strong contingency of Black workers, yet Blacks were more apt to follow the Democratic Party rather than the Communist Party. Other cities, like Indianapolis, were more integrated and Black communities enjoyed greater prosperity, leading them to eschew radical politics and third parties. Many cities did not see the mass influx of migrants after World War I; in 1940, Minneapolis had a Black population of only 4,646, or about 1 percent of the city’s population. Does it follow, then, that Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and Minneapolis did not experience Midwestern Black radicalism? Scholars will have a clearer understanding when Midwestern Studies and the study of Black radicals become more deeply integrated into the American historical practice, when more scholars rigorously interrogate common regional assumptions, and when more archival information is made available. The study presented here is only a beginning.

[end of excerpt]

For tens of thousands of African Americans living in the South in the first half of the twentieth century, the American heartland was the promised land. The urban Midwest spoke to ambitions and hopes of employment, free cultural expression, political rights, and racial equality. Cities like Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, and Chicago beckoned Black migrants from their homes in the South, representing a dream that could no longer be deferred. For one woman, only identified as a “Negro Woman Worker,” the Midwest embodied the American dream. She had moved to Cleveland from a “hell-hole town in Mississippi” to seek employment, a better standard of living, and relief from pervasive racism. Yet, she could not find work, she often went hungry, and she could not afford heat during the winter months. She wrote a letter to the national Communist journal The Working Woman in 1930 to express her frustrations. She asked, “Why don’t the government take care of us while there isn’t any work, so that we don’t have to freeze and starve?” Her frustration did not end at letter writing. She firmly declared she was “ready to fight,” and that “the club and pistol were made for the working class.” Her story does not have a conclusion; there are no more records of this remarkable woman who went out of her way to document and share her ordeal as a Southern migrant in a Midwestern city.

Though an individual story, the “Negro Woman Worker’s” experience paralleled that of thousands of other African American women in the early 1930s. These women, with dreams of racial equality and steady employment, flocked to Midwestern cities, but often found conditions not so different from those they escaped. However, as the letter writer from Cleveland demonstrated, the desperation of the Depression’s hardest-hit population did not indicate apathy or indifference; rather, many Black women during this period represented the fiercest champions of the working class. Due to sexist, racist, and classist systems of oppression, however, finding outlets for this radical activism was often a formidable challenge for these women. As the letter writer showed, though, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) offered avenues heretofore unheard of for Black working-class women in the Midwest.

African American women who participated in Communist-affiliated activities blended their personal and regional histories, their lived experiences, and their ideas of gender and racial equality with party doctrine in a way that established them as important radical activists during the Great Depression. Every individual woman approached her activism differently: Ida Carter bypassed her local church leaders on Chicago’s South Side and organized a strike in coordination with national Communist leaders, seeing it through to a successful conclusion. Carrie Smith stood in front of St. Louis’s City Hall and rallied her fellow workers out of complacency and fear into militant action. She hoisted a brick in one hand, a Bible in the other, and declared, “Girls, we cannot lose!” Mattie Woodson of Detroit officially joined the Communist Party and hosted clandestine meetings in her home, risking her life, job, and reputation. After an anti-eviction riot left her comrades dead, Maggie Jones in Cleveland organized a nurses’ brigade trained in first aid to avoid future tragedy. Thousands of other Black women in the Midwest faded in and out of the Communist Party, attending rallies and protests, but never officially joining the party or making the pages of Communist records. These “Negro Women Workers,” unnamed but no less essential in the struggle, incorporated their notions of race, class, gender, and region to exercise their interpretation of Black radicalism in the Midwest.

A Brick and a Bible documents how, in the span of a few years during the early Great Depression, thousands of African American women in the urban Midwest directly engaged with members of the CPUSA to fight unfair wages, substandard working conditions, and racial discrimination in the workplace as well as hunger, poverty, and homelessness in their communities. From Cleveland to St. Louis, from Chicago to Detroit, these women worked closely with the Communists, sometimes even joining the party, to achieve their short- and long-term goals. When examined through the lenses of gender, race, class, and region, the history of these women, Black radicalism, and the Communist Party in the early Great Depression takes on a new historical importance that challenges how we understand American racial and working-class history today. Because gender, race, class, and region are essential parts of this study, yet were not always central to the CPUSA’s activity, a new term must be realized for these women’s activism. Therefore, I offer Midwestern Black radicalism, formulated as a distinct expression of praxis-based Black radical ideology informed by American Communism, African American community-building, Black women’s history of resistance, and the lived experiences of Black women in the Midwest during the Great Depression. Midwestern Black radicalism directly relates to unique racial, political, geographic, economic, gendered, and spatial characteristics that make up the American heartland. These Black radicals both accepted and challenged the teachings of the CPUSA, while also creating something particular and unique. Midwestern Black radicalism refers to more than the location where these radical activists organized and agitated; rather this particular interpretation of Black radicalism is markedly shaped by many factors. Urban development, industrialization, patterns of migration and residency, and interactions of race, class, and gender in social spaces form the foundation for expressions of Midwestern Black radicalism; as well, individual stories make it come alive. And, most importantly, African American women are the heart of this overlooked radicalism in the heartland. As such, A Brick and a Bible and Midwestern Black radicalism interrogate the crossroads of African American history, gender studies, labor history, and Midwestern studies, calling for a profound re-imagining of how we remember and interpret these women’s stories.

The burden of defining the Midwest has kept regional historians busy for decades, and though it probably remains an impossible task, it deserves a brief mention. R. Douglas Hunt warns that scholars should not place too much emphasis on geographical boundaries, as they are a “mental construct.” Though climate, environment, geography, and location “set the parameters” for our regional understanding, the distinctiveness ultimately comes from a social and cultural understanding. This study posits the Midwest as a shared cultural and social space marked by distinctive characteristics of residential segregation, migratory patterns, dependence on Black labor, light and heavy industry, virulent racism, and expansion of radical interracial coalition building. This study focuses on four Midwestern cities: Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Cleveland, but the geographic understanding of the regional Midwest extends to Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, and Western Pennsylvania. It is a seemingly simple geographic region ranging from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians, north of the Ohio River and the Missouri Compromise border. It is known in the popular American imagination as the land of “amber waves of grain,” dairy farms, and conservative thinking. This region has never been known for its radicalism; in fact, in 1922 philosopher John Dewey observed that the Midwest “has been the middle in every sense of the word and in every movement.” The region operated as a stabilizing force, whose people “never had an interest in ideas as ideas, nor in science and art for what they may do in liberating and elevating the human spirit.” This popular notion of an ordinary space and region only covers for a deeply traumatic past. Historian Brent Campney argues that the Midwest’s claim to “pastoral meritocracy” was maintained through racial exclusion and bloodshed and documents a disturbing trend of violence, brutality, and lynchings in the region. In her work on the Black Midwest, Ashley Howard adds that “economic and race oppression acted as co-conspirators,” resulting in explosive conditions. Though she specifically addresses urban riots post-World War II, Howard’s observations on economics, race, and the Midwest are fitting for the first half of the twentieth century as well. The heartland is often synonymous with traditional white American values and politics, but the lived experiences of African Americans in the heartland, regardless of era, were marked by prejudice, violence, segregation, and struggle.

Economic potential brought migrants to Midwestern cities during the Great Migration, however prevailing racism limited economic opportunities. The influx of Black Southerners shaped the character of these cities in ways unparalleled in the Northeast. Midwestern cities were home to millions of people, thriving industries, vibrant cultural centers, robust political landscapes, and tumultuous race and class tensions. In 1930, the Midwest boasted four of the largest cities in the United States: Chicago (second, with 3.3 million people, 6.9 percent Black), Detroit (fourth, with 1.5 million, 7.7 percent Black), Cleveland (sixth, with 900,429, 7.9 percent Black), and St. Louis (seventh, with 821,960, 11.4 percent Black). While New York City certainly had a larger overall population and more African Americans called it home, the percentage of Blacks in the city in 1930 was only 4.73 percent, less than the percentage of Blacks in each of the ten most populated Midwestern cities. Out of the five boroughs, only Manhattan’s percentage was greater, with an African American population of 12 percent in 1930. While New York City has often received the most attention in terms of the numbers of Southern migrants, the drastic percentage increase of African Americans in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland significantly altered the economic, political, and social landscape in ways unseen in other urban areas.

Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis showed striking similarities in terms of industry, population, neighborhood arrangement, and politics, as this book documents. As Cedric Robinson argues, Black radicalism begins with tension, and racial tension was the defining feature during the 1920s and 30s for Midwestern cities. Therefore, Midwestern Black radicalism begins with the Great Migration and gains momentum with the Great Depression. Thousands of workers poured into Midwestern cities in pursuit of jobs and a less racist social order, however they faced substantial challenges. While Jim Crow did not have legal standing in cities like St. Louis or Cleveland, de facto segregation practices prevented equal opportunity for the cities’ newest residents. Unions habitually excluded Blacks from membership, restaurants and other public places still allowed segregated facilities, and discriminatory housing policies relegated working-class African Americans to the cities’ least desirable areas. From Chicago’s South Side to Cleveland’s Central Area, and from East St. Louis to Detroit’s Black Bottom, working-class Black Midwesterners experienced some of the worst living conditions urban areas had to offer. Lack of indoor plumbing, neglectful landlords, overcrowded apartments, and ramshackle buildings characterized many Black migrants’ new homes. Recent migrants to the urban Midwest found their situation a far cry from the “paradise” that Black newspapers advertised, and, while improved in many respects, Midwestern urban areas still resembled those in the South. Yet each Midwestern city stood on its own, as each experienced race, class, and gender relations differently. The stories set in each city reveal certain aspects of Midwestern Black radicalism, and while many of the themes overlap, each city was unique. Midwestern Black radicalism during the 1930s necessarily involved organizing at many levels, addressing local politics, changing strategic tactics, and incorporating themes of motherhood, community, religion, and local politics. As these women show, adaptability to the city and the historical conditions was key.

This study is in a part a reclamation effort, but it is by no means exhaustive on the subject of Midwestern Black radicalism. Some Midwestern cities, such as Milwaukee, had a strong contingency of Black workers, yet Blacks were more apt to follow the Democratic Party rather than the Communist Party. Other cities, like Indianapolis, were more integrated and Black communities enjoyed greater prosperity, leading them to eschew radical politics and third parties. Many cities did not see the mass influx of migrants after World War I; in 1940, Minneapolis had a Black population of only 4,646, or about 1 percent of the city’s population. Does it follow, then, that Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and Minneapolis did not experience Midwestern Black radicalism? Scholars will have a clearer understanding when Midwestern Studies and the study of Black radicals become more deeply integrated into the American historical practice, when more scholars rigorously interrogate common regional assumptions, and when more archival information is made available. The study presented here is only a beginning.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

Acknowledgments

List of Abbreviations

Introduction: Midwestern Black Radicalism

1. “Lose Your Fear”: Rallying Labor in Detroit

2. “Why Can’t We Get a Living Wage”: Community and Labor Organizing in St. Louis

3. “Put Up a Fight”: Evictions, Elections, and Strikes in Chicago

4. “We’ll Not Starve Peacefully”: Black Women’s Revolution and Reform in Cleveland

Conclusion: Midwestern Black Radicalism Matters

Appendix: Black Populations in Selected Cities

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Gallery of illustrations

List of Abbreviations

Introduction: Midwestern Black Radicalism

1. “Lose Your Fear”: Rallying Labor in Detroit

2. “Why Can’t We Get a Living Wage”: Community and Labor Organizing in St. Louis

3. “Put Up a Fight”: Evictions, Elections, and Strikes in Chicago

4. “We’ll Not Starve Peacefully”: Black Women’s Revolution and Reform in Cleveland

Conclusion: Midwestern Black Radicalism Matters

Appendix: Black Populations in Selected Cities

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Gallery of illustrations

Recenzii

"A Brick and a Bible is an impressively informative and original work of meticulous historical research and scholarship. Exceptionally well written, organized and presented, [this book] is a unique and highly recommended addition to community, college, and library Black History, Women's History, American History, and Feminist Theory collections."—Helen Dumont, Midwest Book Review

“In A Brick and a Bible, radical Black working-class women take center stage as the shapers of their own destinies. By charting these women’s diverse engagement with Communist-affiliated groups across the Midwest, Melissa Ford reveals the centrality of the region as a key site for Black radical politics. With clarity and grace, Ford recovers the stories of Black women determined to bring an end to race, gender, and class oppression.”—Keisha N. Blain, author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

“Ford challenges lingering misconceptions of a Midwest that is white, homogenous, conservative, and male-dominated. Through her investigation of Black women’s radical activism not only does she articulate the uniqueness of the region, but she also argues that intraregional particularities must be considered. Ford convincingly argues that the radical Black Midwest is not only place, but praxis.”—Ashley Howard, author of Then the Burnings Began: Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence

“Thanks to Melissa Ford, Black women’s struggles against ‘triple oppression’ come alive on the pages of this book. A Brick and a Bible illustrates how Black women harnessed the energies of urban neighborhoods, Communist Party campaigns, and union drives in pursuit of liberation.”—Erik S. Gellman, author of Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles through the Lens of Art Shay

“This is a tightly focused account of Black women’s radical activist in Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Cleveland during the Depression. Roughly a quarter of the book’s content (the Chicago chapter) is on Illinois history. The author illuminates the lives, terrible working conditions, and political activism (anti-eviction protests, labor organizing, communist party organizing, campaigns for elected office, etc.) of Black women in Chicago, propelled by the Depression.”—Illinois State Historical Society Awards Selection Committee

“In her innovative study of four Midwestern cities during the Depression era, historian Melissa Ford reveals an emergent pattern of social crisis, involvement, and Black women’s radical activism. A Brick and a Bible examines the evidence and creates a framework for understanding this tradition of social action by Black women. . . . [T]his book is well worth an investment of time for study and, as the author states, as a basis for further research.”—Joel Wendland-Liu, People’s World

“Ford’s book is an important contribution to understanding the role of Black women as activists as well as Black Midwest studies and should be read by all who are interested in understanding how yet another marginalized group managed to raise hell when they needed to.”—Alonzo M. Ward, Missouri Historical Review

“Ford splendidly makes the case for paying greater attention to the history of Midwestern Black radicalism. She expertly fills gaps in historical narratives and demonstrates the continuing relevance, in the age of Black Lives Matter, of an earlier generation of African American woman activists.”—Keith Gilyard, The Journal of African American History

“A Brick and a Bible artfully reconstructs Black women’s contribution to interwar radicalism. Importantly, Ford is attentive to differences among the women’s life experiences and approach to activism, offering a multidimensional history of midwestern radicalism and Black women’s role in it.”—Victoria W. Wolcott, author of Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement

“In A Brick and a Bible, radical Black working-class women take center stage as the shapers of their own destinies. By charting these women’s diverse engagement with Communist-affiliated groups across the Midwest, Melissa Ford reveals the centrality of the region as a key site for Black radical politics. With clarity and grace, Ford recovers the stories of Black women determined to bring an end to race, gender, and class oppression.”—Keisha N. Blain, author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

“Ford challenges lingering misconceptions of a Midwest that is white, homogenous, conservative, and male-dominated. Through her investigation of Black women’s radical activism not only does she articulate the uniqueness of the region, but she also argues that intraregional particularities must be considered. Ford convincingly argues that the radical Black Midwest is not only place, but praxis.”—Ashley Howard, author of Then the Burnings Began: Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence

“Thanks to Melissa Ford, Black women’s struggles against ‘triple oppression’ come alive on the pages of this book. A Brick and a Bible illustrates how Black women harnessed the energies of urban neighborhoods, Communist Party campaigns, and union drives in pursuit of liberation.”—Erik S. Gellman, author of Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles through the Lens of Art Shay

“This is a tightly focused account of Black women’s radical activist in Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Cleveland during the Depression. Roughly a quarter of the book’s content (the Chicago chapter) is on Illinois history. The author illuminates the lives, terrible working conditions, and political activism (anti-eviction protests, labor organizing, communist party organizing, campaigns for elected office, etc.) of Black women in Chicago, propelled by the Depression.”—Illinois State Historical Society Awards Selection Committee

“In her innovative study of four Midwestern cities during the Depression era, historian Melissa Ford reveals an emergent pattern of social crisis, involvement, and Black women’s radical activism. A Brick and a Bible examines the evidence and creates a framework for understanding this tradition of social action by Black women. . . . [T]his book is well worth an investment of time for study and, as the author states, as a basis for further research.”—Joel Wendland-Liu, People’s World

“Ford’s book is an important contribution to understanding the role of Black women as activists as well as Black Midwest studies and should be read by all who are interested in understanding how yet another marginalized group managed to raise hell when they needed to.”—Alonzo M. Ward, Missouri Historical Review

“Ford splendidly makes the case for paying greater attention to the history of Midwestern Black radicalism. She expertly fills gaps in historical narratives and demonstrates the continuing relevance, in the age of Black Lives Matter, of an earlier generation of African American woman activists.”—Keith Gilyard, The Journal of African American History

“A Brick and a Bible artfully reconstructs Black women’s contribution to interwar radicalism. Importantly, Ford is attentive to differences among the women’s life experiences and approach to activism, offering a multidimensional history of midwestern radicalism and Black women’s role in it.”—Victoria W. Wolcott, author of Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement

Descriere

A Brick and a Bible examines how African American working-class women, many of whom had just migrated to “the promised land” only to find hunger, cold, and unemployment, forged a region of revolutionary potential.