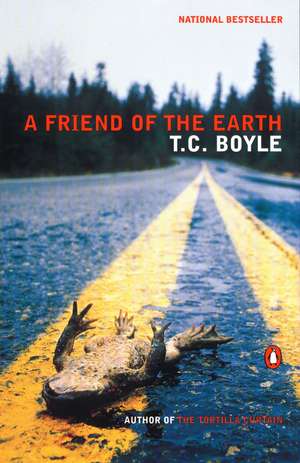

A Friend of the Earth

Autor Tom Coraghessan Boyleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2001 – vârsta de la 18 ani

In the tradition of The Tortilla Curtain, T.C. Boyle blends idealism and satire in a story that addresses the universal questions of human love and the survival of the species. In the year 2025 global warming is a reality, the biosphere has collapsed, and 75-year-old environmentalist Ty Tierwater is eking out a living as care-taker of a pop star's private zoo when his second ex-wife re-enters his life.

Both gritty and surreal, A Friend of the Earth represents a high-water mark in Boyle's career-his deep streak of social concern is effortlessly blended here with genuine compassion for his characters and the spirit of sheer exhilarating playfulness readers have come to expect from his work.

Both gritty and surreal, A Friend of the Earth represents a high-water mark in Boyle's career-his deep streak of social concern is effortlessly blended here with genuine compassion for his characters and the spirit of sheer exhilarating playfulness readers have come to expect from his work.

Preț: 123.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 186

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.67€ • 24.50$ • 20.01£

23.67€ • 24.50$ • 20.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780141002057

ISBN-10: 0141002050

Pagini: 349

Dimensiuni: 127 x 193 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

ISBN-10: 0141002050

Pagini: 349

Dimensiuni: 127 x 193 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Recenzii

Funny and touching, antic and affecting . . . while Boyle's humor is as black as ever, he demonstrates that satire can coexist with psychological realism, comedy with compassion." —Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

"As disaster tales go, this is a sly, hip one...Boyle has always liked to play circus barker for life's extremes and what better freak show than the environmental apocalypse itself?" —The Washington Post

"Both entertaining and informative...hits like a warning shot from twenty-five years into the future." —Chicago Tribune

"As disaster tales go, this is a sly, hip one...Boyle has always liked to play circus barker for life's extremes and what better freak show than the environmental apocalypse itself?" —The Washington Post

"Both entertaining and informative...hits like a warning shot from twenty-five years into the future." —Chicago Tribune

Notă biografică

T. C. Boyle is the author of eleven novels, including World's End (winner of the PEN/FaulknerAward), Drop City (a New York Times bestseller and finalist for the National Book Award), and The Inner Circle. His most recent story collections are Tooth and Claw and The Human Fly and Other Stories.

Extras

PrologueSanta Ynez, November 2025

I'm out feeding the hyena her kibble and chicken backs and doing what I can to clean up after the latest storm, when the call comes through. It's Andrea. Andrea Knowles Cotton Tierwater, my ex-wife, my wife of a thousand years ago, when I was young and vigorous and relentlessly virile, the woman who routinely chained herself to cranes and bulldozers and seven-hundred-thousand-dollar Feller Buncher machines back in the time when we thought it mattered, the woman who helped me raise my daughter, the woman who made me crazy. Jesus Christ. If somebody had to come, why couldn't it be Teo. He'd be easier—him I could just kill. Bang-bang. And the Lily would have something more than chicken backs for dinner.

Anyway, there are trees down everywhere and the muck is tugging at my gum boots like a greedy sucking mouth, a mouth that's going to pull me all the way down eventually, but not yet. I might be seventy-five years old and my shoulders might feel as if they're attached at the joint with fishhooks, but the new kidney they grew me is still processing fluids just fine, thank you, and I can still outwork half the spoonfed cretins on this place. Besides, I have skills, special skills—I'm an animal man and there aren't many of us left these days, and my boss, Maclovio Pulchris, appreciates that. And I'm not name-dropping here, not necessarily—just stating the facts. I manage the man's private menagerie, the last surviving one in this part of the world, and it's an important—scratch that, vital—reservoir for zoo-cloning and the distribution of what's left of the major mammalian species. And you can say what you will about pop stars or the quality of his music or even the way he looks when he takes his hat and sunglasses off and you can see what a ridiculous little crushed nugget of a head he was born with, but I'll say this—he's a friend of the animals.

Of course, there isn't going to be anything left of the place if the weather doesn't let up. It's not even the rainy season—or what we used to qualify as the rainy season, as if we knew anything about it in the first place—but the storms are stacked up over the Pacific like pool balls on a billiard table and not a pocket in sight. Two days ago the wind came up in the night, ripped the roof off of one of the back pens and slammed it like a giant Frisbee into the Lupine Hill condos across the way. Mac didn't particularly care about that—nobody's insured for weather anymore and any and all lawsuits are automatically thrown out of court, so don't even ask—but what hurt was the fact that the Patagonian fox got loose, and that's the last native-born individual known to be in existence on this worn-out planet, and we still haven't found the thing. Not a clue. No tracks, no nothing. She just disappeared, as if the storm had picked her up like Dorothy and set her down in the place where the extinct carnivores of all the ages run riot through fields of hobbled game—or in the middle of a freeway, where to the average motorist she'd be nothing more than a dog on stilts. The pangolins, they're gone too. And less than fifty of them out there in the world. It's a crime, but what can you do—call up the search and rescue? We've all been hit hard. Floods, winds, thunder and lightning, even hail. There are plenty of people without roofs over their heads, and right here in Santa Barbara County, not just Los Andiegoles or San Jose Francisco.

So Lily, she's giving me a long steady look out of the egg yolks of her eyes, and I'm lucky to have chicken backs what with the meat situation lately, when the pictaphone rings (think Dick Tracy, because the whole world's a comic strip now). The sky is black—not gray, black—and it can't be past three in the afternoon. Everything is still, and I smell it like a gathering cloud, death, the death of everything, hopeless and stinking and wasted, the pigment gone from the paint, the paint gone from the buildings, cars abandoned along the road, and then it starts raining again. I talk to my wrist (no picture, though—the picture button is set firmly and permanently in the off position—why would I want to show this wreck of a face to anybody?). "Yeah?" I shout, and the rain is heavier, wind-driven now, snapping in my face like a wet towel.

"Ty?"

The voice is cracked and blistered, like the dirt here when the storms move on to Nevada and Arizona and the sun comes back to pound us all with its unfiltered melanomic might, but I recognize it right away, twenty years notwithstanding. It's a voice that does something physical to me, that jumps out of the circumambient air and seizes hold of me like a thing that lives off the blood of other things. "Andrea? Andrea Cotton?" Half a beat. "Jesus Christ, it's you, isn't it?"

Soft and seductive, the wind rising, Lily fixing me from behind the chicken wire as if I'm the main course: "No picture for me?"

"What do you want, Andrea?"

"I want to see you."

"Sorry, nobody sees me."

"I mean in person, face to face. Like before."

Rain streams from my hat. One of the sorry inbred lions starts coughing its lungs out, a ratcheting, oddly mechanical sound that drifts across the weedlot and ricochets off the monolithic face of the condos. I'm trying to hold back a whole raft of feelings, but they keep bobbing and pitching to the surface, threatening to break loose and shoot the rapids once and for all. "What for?"

"What do you think?"

"I don't know—to run down my debit cards? Fuck with my head? Save the planet?"

Lily stretches, yawns, shows me the length of her yellow canines and the big crushing molars in back. She should be out on the veldt, cracking up giraffe bones, extracting marrow from the vertebrae, gnawing on hoofs. Except that there is no veldt, not anymore, and no giraffes either. Something unleashed in my brain shouts, IT'S ANDREA! And it is. Andrea's voice coming back at me. "No, fool," she says. "For love."

I'm out feeding the hyena her kibble and chicken backs and doing what I can to clean up after the latest storm, when the call comes through. It's Andrea. Andrea Knowles Cotton Tierwater, my ex-wife, my wife of a thousand years ago, when I was young and vigorous and relentlessly virile, the woman who routinely chained herself to cranes and bulldozers and seven-hundred-thousand-dollar Feller Buncher machines back in the time when we thought it mattered, the woman who helped me raise my daughter, the woman who made me crazy. Jesus Christ. If somebody had to come, why couldn't it be Teo. He'd be easier—him I could just kill. Bang-bang. And the Lily would have something more than chicken backs for dinner.

Anyway, there are trees down everywhere and the muck is tugging at my gum boots like a greedy sucking mouth, a mouth that's going to pull me all the way down eventually, but not yet. I might be seventy-five years old and my shoulders might feel as if they're attached at the joint with fishhooks, but the new kidney they grew me is still processing fluids just fine, thank you, and I can still outwork half the spoonfed cretins on this place. Besides, I have skills, special skills—I'm an animal man and there aren't many of us left these days, and my boss, Maclovio Pulchris, appreciates that. And I'm not name-dropping here, not necessarily—just stating the facts. I manage the man's private menagerie, the last surviving one in this part of the world, and it's an important—scratch that, vital—reservoir for zoo-cloning and the distribution of what's left of the major mammalian species. And you can say what you will about pop stars or the quality of his music or even the way he looks when he takes his hat and sunglasses off and you can see what a ridiculous little crushed nugget of a head he was born with, but I'll say this—he's a friend of the animals.

Of course, there isn't going to be anything left of the place if the weather doesn't let up. It's not even the rainy season—or what we used to qualify as the rainy season, as if we knew anything about it in the first place—but the storms are stacked up over the Pacific like pool balls on a billiard table and not a pocket in sight. Two days ago the wind came up in the night, ripped the roof off of one of the back pens and slammed it like a giant Frisbee into the Lupine Hill condos across the way. Mac didn't particularly care about that—nobody's insured for weather anymore and any and all lawsuits are automatically thrown out of court, so don't even ask—but what hurt was the fact that the Patagonian fox got loose, and that's the last native-born individual known to be in existence on this worn-out planet, and we still haven't found the thing. Not a clue. No tracks, no nothing. She just disappeared, as if the storm had picked her up like Dorothy and set her down in the place where the extinct carnivores of all the ages run riot through fields of hobbled game—or in the middle of a freeway, where to the average motorist she'd be nothing more than a dog on stilts. The pangolins, they're gone too. And less than fifty of them out there in the world. It's a crime, but what can you do—call up the search and rescue? We've all been hit hard. Floods, winds, thunder and lightning, even hail. There are plenty of people without roofs over their heads, and right here in Santa Barbara County, not just Los Andiegoles or San Jose Francisco.

So Lily, she's giving me a long steady look out of the egg yolks of her eyes, and I'm lucky to have chicken backs what with the meat situation lately, when the pictaphone rings (think Dick Tracy, because the whole world's a comic strip now). The sky is black—not gray, black—and it can't be past three in the afternoon. Everything is still, and I smell it like a gathering cloud, death, the death of everything, hopeless and stinking and wasted, the pigment gone from the paint, the paint gone from the buildings, cars abandoned along the road, and then it starts raining again. I talk to my wrist (no picture, though—the picture button is set firmly and permanently in the off position—why would I want to show this wreck of a face to anybody?). "Yeah?" I shout, and the rain is heavier, wind-driven now, snapping in my face like a wet towel.

"Ty?"

The voice is cracked and blistered, like the dirt here when the storms move on to Nevada and Arizona and the sun comes back to pound us all with its unfiltered melanomic might, but I recognize it right away, twenty years notwithstanding. It's a voice that does something physical to me, that jumps out of the circumambient air and seizes hold of me like a thing that lives off the blood of other things. "Andrea? Andrea Cotton?" Half a beat. "Jesus Christ, it's you, isn't it?"

Soft and seductive, the wind rising, Lily fixing me from behind the chicken wire as if I'm the main course: "No picture for me?"

"What do you want, Andrea?"

"I want to see you."

"Sorry, nobody sees me."

"I mean in person, face to face. Like before."

Rain streams from my hat. One of the sorry inbred lions starts coughing its lungs out, a ratcheting, oddly mechanical sound that drifts across the weedlot and ricochets off the monolithic face of the condos. I'm trying to hold back a whole raft of feelings, but they keep bobbing and pitching to the surface, threatening to break loose and shoot the rapids once and for all. "What for?"

"What do you think?"

"I don't know—to run down my debit cards? Fuck with my head? Save the planet?"

Lily stretches, yawns, shows me the length of her yellow canines and the big crushing molars in back. She should be out on the veldt, cracking up giraffe bones, extracting marrow from the vertebrae, gnawing on hoofs. Except that there is no veldt, not anymore, and no giraffes either. Something unleashed in my brain shouts, IT'S ANDREA! And it is. Andrea's voice coming back at me. "No, fool," she says. "For love."

Descriere

Blending idealism and satire, this story set in the year 2025 addresses universal questions of human love and the survival of the species. Global warming has collapsed the biosphere, and 75-year-old environmentalist Ty Tierwater is eking out a living as care-taker of a pop star's private zoo when his second ex-wife reenters his life.