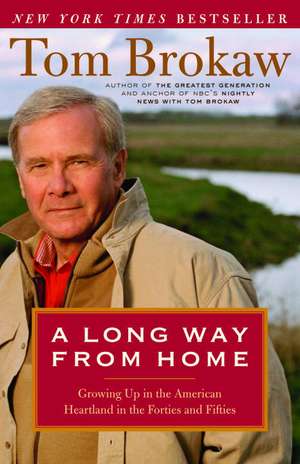

A Long Way from Home: Growing Up in the American Heartland in the Forties and Fifties

Autor Tom Brokawen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2003 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Audies (2004)

Preț: 119.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.84€ • 24.82$ • 19.20£

22.84€ • 24.82$ • 19.20£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 16-22 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375759352

ISBN-10: 0375759352

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 44 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Ediția:Rh Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375759352

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 44 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Ediția:Rh Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Tom Brokaw is the author of seven bestsellers: The Greatest Generation, The Greatest Generation Speaks, An Album of Memories, Boom!, The Time of Our Lives, A Long Way from Home, and A Lucky Life Interrupted. A native of South Dakota, he graduated from the University of South Dakota, and began his journalism career in Omaha and Atlanta before joining NBC News in 1966. Brokaw was the White House correspondent for NBC News during Watergate, and from 1976 to 1981 he anchored Today on NBC. He was the sole anchor and managing editor of NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw from 1983 to 2005. He continues to report for NBC News, producing long-form documentaries and providing expertise during breaking news events. Brokaw has won every major award in broadcast journalism, including two DuPonts, three Peabody Awards, and several Emmys, including one for lifetime achievement. In 2014, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He lives in New York and Montana.

Extras

Chapter 1

A Long Way from Home

In 1962, I put my home state of South Dakota in a rearview mirror and drove away. I was uncertain of my final destination but determined to get well beyond the slow rhythms of life in the small towns and rural culture of the Great Plains. I thought that the influences of the people, the land, and the time during my first twenty-two years of life were part of the past. But gradually I came to know how much they meant to my future, and so I have returned often as part of a long pilgrimage of renewal.

When I do return, my wardrobe and home address are New York, my job is high-profile, and my bank account is secure, but when I enter a South Dakota café or stop for gas, I am just someone who grew up around here, left a while back, and never really answers when he's asked, "When you gonna move back home?" I am caught in that place all too familiar to small-state natives who have moved on to a rewarding life in larger arenas: I don't want to move back, but in a way I never want to leave. I am nourished by every visit.

On those trips back to the Great Plains I always try to imagine the land before it was touched by rails and plows, fences and roads. I can still drive off the pavement of South Dakota highways, find a slight elevation in the prairie flatness, and look to a distant horizon, across untilled grassland, and with no barbed wire or telephone poles or dwellings to break the plane of earth and sky. It is at once majestic and intimidating. More than a century after the first white settlers began to arrive, the old Dakota Territory remains a place where nature rules.

On a still, hot late-summer day, after a wet spring in the northern plains of South Dakota, the rich golden fields of wheat and barley, the deep green landscapes of corn and alfalfa surrounding the neat white farmhouses framed by red barns and rows of sheltering trees, give a glow of goodness and prosperity. It is hard to remember this was once a place of despair brought on by a cruel combination of nature and economic forces at their most terrifying.

This was a bleak and hostile land in the Dirty Thirties.

Families struggled against drought, grasshoppers, collapsed markets, and fear. Billowing clouds of topsoil, lifted off the land by fierce winds, reduced the sun to a faint orb; in April 1934, traces of Great Plains soil were found as far east as Washington, D.C. One report said the dust storm was so bad it left a film on President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Oval Office desk.

This is where my mother and father were raised and came of age, at the height of the Depression. It is where I was born and spent the first twenty-two years of my life, and it remains always familiar, however long I have been away. Whenever I return, I try to imagine the struggles my parents and everyone else went through here in the thirties. That time formed them-and through them, it formed me. I am in awe of how they emerged, and I am grateful for their legacy, although I have been an imperfect steward.

I left in 1962, hungry for bright lights, big cities, big ideas, and exotic places well beyond the conventions and constraints of my small-town childhood, but forty years later I still call South Dakota home. Time and distance have sharpened my understanding of the forces that shaped my parents' lives and mine so enduringly. Those forces are the grid on which I've come to rely, in good times and bad.

In the late 1800s, the Dakota Territory was one of the last frontiers in America, a broad, flat grassland where Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and their followers in the Sioux nation were hunters and warriors on horseback, determined to hold their land against the persistent invasion of white settlers who wanted to farm, ranch, and build towns along the railroad lines racing westward from the industrialized East and Midwest.

The Sioux won some battles, notably Little Big Horn in Montana, but they lost the war. The Dakota Territory was divided into two states, one north and one south, in 1889. My ancestors were among the early settlers in what became South Dakota.

My father, Anthony Orville Brokaw, was born on October 17, 1912, the last of ten children of William and Elizabeth Brokaw. His grandfather Richard P. Brokaw, the descendant of Huguenots who immigrated early to New York, had made his way to the southwestern Dakota Territory by covered wagon following the Civil War. He farmed and worked on the railroad before heading north in 1881 to found the town of Bristol and a small hotel, the Brokaw House, at the planned intersection of the north-south and east-west rail lines, eight years before statehood.

My mother is the eldest daughter of Jim and Ethel Conley, who farmed south of Bristol. Ethel took the train from Bristol to Minneapolis, her hometown, for Jean's birth; then mother and daughter returned to the remote corner of the prairie where Jim was tilling the ground behind teams of horses.

In the summer of 1996 my mother and I returned to the northern plains, the womb of her life and mine, for a visit that was at once nostalgic, reassuring, and a commentary on the social and economic changes in this country in the second half of the twentieth century.

As we drove east along Highway 212 from Aberdeen, South Dakota, toward Bristol, we passed a giant Wal-Mart with a parking lot full of late-model cars and pickup trucks; there were expensive new houses on large lots, and broad streets well beyond the city limits; giant John Deere combines, worth more than $100,000 apiece, moved efficiently through ripe fields of wheat, disgorging the small, valuable kernels into a truck of the kind called a Twin Hopper for its side-by-side bins that can hold a combined total of one thousand bushels. Many of the combines have air-conditioning and stereos in their cabs, to go with the computer monitoring systems that record the yield while the harvest is under way. Many of the smaller farms have been consolidated into larger tracts and organized as corporations with sophisticated business models relying on the efficiencies of mass production and the yield of genetically engineered grains. Much has changed, but still, a drought or a sudden hailstorm or a freak cold snap can undo all of the best planning and agriculture science.

Modern technology hasn't completely eliminated what my mother remembers of the sweat and heartache required for a farmer's life. But it is a far different world than when I was a child. As a town kid, I was attracted to the farm only by the prospect of a horseback ride or the chance to drive a tractor. I had no inclination for the work, much of it unending and involving uncooperative livestock in a muck of mud and manure or working in fields beneath a blazing sun.

South Dakota is two states, really, divided by the Missouri River. In a larger sense, the river also divides the Midwest from the Far West. East of the Missouri, in the midwestern half, small towns shaded by trees planted a hundred years ago are separated by clusters of farm buildings and quadrangles of tilled ground producing corn, soybeans, wheat, rye, and sunflowers.

As you move across the Missouri, into what we call West River country, the change is abrupt. On airplanes flying across South Dakota east to west, I like to tell my fellow passengers to watch the cultivated fields, the gold and green color schemes of corn and wheat, suddenly give way to the muted browns and the untilled sod once we cross the river. It is such a stunning change, it is as if someone flipped a page, and then another change comes two hundred miles farther. At the very western edge of the state, the prairie breaks up into the arid and eerily beautiful Badlands and then gives way to the Black Hills, a small scenic mountain range the Sioux people called Paha Sapa, the most sacred of their land.

I have lived and traveled in every quarter of the state, and I am constantly struck by the rawness of it all, even now, more than 125 years after the first significant wave of white settlers began trying to tame it. Even a summer night in a substantial dwelling in an established town can be a reminder of the primal forces of the old Dakota Territory when a storm blows up, filling the sky with mountainous thunderstorms and bowing the tall cottonwoods with cold winds that seem to begin somewhere near the Arctic Circle.

I am particularly attached to the Missouri River, that ancient artery that begins in central Montana and powers its way north before beginning its long east-by-southeast trek across the flat landscape of the Dakotas and along the borders of Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri. Large dams have slowed but not completely conquered the river of Lewis and Clark, the Sioux, the Crow, Omaha, and Santee tribes. Whenever I return to my home state I always try to swim in the river channel, just to feel its restless currents again, as a reminder of my early struggles to master them as a beginning swimmer. They taught me to understand force and use it to my advantage, taught me that to make progress often means giving a little.

On this trip back to Bristol with my mother in 1996, as I steered our rental car toward the distant eastern horizon, an old sensation returned. Up there in the northern latitudes, less than two hundred miles from the Canadian border, I feel as if I am riding the curvature of the earth, silhouetted against the sweeping arc of sky that so diminishes all below. I have now lived two thirds of my life outside these familiar surroundings, yet whenever I return I am at peace, and always a little excited to know that this place has a claim on me.

I am named for my maternal great-grandfather Thomas Conley, the son of Irish immigrants, who was working as a railroad conductor in St. Paul when he was attracted by the abundance of affordable farmland in Day County, South Dakota. Tom and his wife, Mathilda, moved in 1897 to Webster, the Day County seat, where Tom opened a saloon before moving on to a section and a half of prairie, 960 acres, southwest of Bristol, where together he and Mathilda began farming with horse-drawn machinery.

Tom Conley, at six feet a tall man in those days, quickly established a reputation as a hardworking and efficient farmer who, according to local lore, took off only one day a year: the Fourth of July. On Independence Day he'd drive a horse-drawn wagon from the farm to Bristol's main street for the celebrations, shouting to everyone, "Hurray for the Fourth of July!"

Tom and Mathilda Conley prospered in the early days of the twentieth century, sending three of their four sons to college. One went on to law school and another to medical school. My mother's father, Jim, graduated from a pharmacy college in Minneapolis, but he preferred farming to pharmacy and returned to Day County with his bride, Ethel Baker, a handsome and lively daughter of a foreman at Pillsbury Mills in the Twin Cities. As a wedding present, Tom Conley gave his son and new wife as a wedding present a mortgaged quarter-section, 160 treeless acres just north of his farm. It was so barren that Jim Conley often said it contained not even a rusty nail; black-and-white pictures from that time are startling in their bleakness.

A quarter-section of land was the allotment that the seminal figure of prairie literature, Per Hansa, filed for when he took his family into the Dakota Territory, in O. E. Rolvaag's classic Giants in the Earth. Powerful winds, broad horizons, "And sun! And still more sun!"-as Rolvaag vividly described this part of America that stretches from the Canadian border to Oklahoma, from Minnesota to the middle of Montana.

It was little changed in the first quarter of the twentieth century, when my parents were youngsters. Just as for Per Hansa and his fellow Norwegian settlers, it was a demanding place, whatever the season, for those who came to farm or to establish the small towns where agriculture and commerce intersected across the grassland. It is a place that reflects a century of transformation in America.

When my mother was born, in November 1917, the world was in turmoil. That same month Lenin took control of the Russian government and the Communist revolution was under way. America entered World War I at last, and General John Pershing led American forces into Europe. The war was an international tragedy but a bonanza for American farmers, as they moved into mechanized equipment and turned their grain fields into the bread basket of the world. Farmland in the heart of the corn belt brought prices two and three times what they had been just three years earlier.

Jim and Ethel were making enough money to start a new home and buy a Model T, the little black car that was the centerpiece of Henry Ford's rapidly growing empire. Neither of my grandparents left behind a personal account of their hopes and dreams, but I suspect they thought the farm would become their life work. Instead, it became a heartbreaking burden.

By 1930 they were trapped between a prolonged drought across the Great Plains and economic chaos in the international markets. Jim and Ethel, my mother, Jean, and her younger sister, Marcia, were hostage to the cruelties of what came to be known as the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1932, the average net per capita income on family farms fell from $2,297 to $74.

Jim Conley admired Herbert Hoover, a native of nearby Iowa and a brilliant mining engineer who was an international hero for his organization of food programs for Europe following the devastation of World War I. It is likely that Jim voted for Hoover in the 1928 presidential election. But what happened in the thirties would make my grandfather an ardent Democrat for his remaining days.

Jim and Ethel Conley's hopes for a long life on the farm were wiped out. By 1932, Jim was feeding his corn crop to his hogs because doing so was more economical than taking it to market, where it would have brought less than a nickel a bushel. By my mother's junior year in high school, the Conley farm days were over. The bank foreclosed and the family moved to nearby Bristol.

Because my parents came of age during the Great Depression, it never completely left their consciousness. It would be too melodramatic to say they carried lasting scars, but it would be equally inaccurate to describe the Depression as just a benign passage in their lives. The residual effect went well beyond the bleak economics of the time. Living through the Great Depression formed other lasting values: an unalloyed work ethic, thrift, compassion, and, perhaps most important, perspective.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Long Way from Home

In 1962, I put my home state of South Dakota in a rearview mirror and drove away. I was uncertain of my final destination but determined to get well beyond the slow rhythms of life in the small towns and rural culture of the Great Plains. I thought that the influences of the people, the land, and the time during my first twenty-two years of life were part of the past. But gradually I came to know how much they meant to my future, and so I have returned often as part of a long pilgrimage of renewal.

When I do return, my wardrobe and home address are New York, my job is high-profile, and my bank account is secure, but when I enter a South Dakota café or stop for gas, I am just someone who grew up around here, left a while back, and never really answers when he's asked, "When you gonna move back home?" I am caught in that place all too familiar to small-state natives who have moved on to a rewarding life in larger arenas: I don't want to move back, but in a way I never want to leave. I am nourished by every visit.

On those trips back to the Great Plains I always try to imagine the land before it was touched by rails and plows, fences and roads. I can still drive off the pavement of South Dakota highways, find a slight elevation in the prairie flatness, and look to a distant horizon, across untilled grassland, and with no barbed wire or telephone poles or dwellings to break the plane of earth and sky. It is at once majestic and intimidating. More than a century after the first white settlers began to arrive, the old Dakota Territory remains a place where nature rules.

On a still, hot late-summer day, after a wet spring in the northern plains of South Dakota, the rich golden fields of wheat and barley, the deep green landscapes of corn and alfalfa surrounding the neat white farmhouses framed by red barns and rows of sheltering trees, give a glow of goodness and prosperity. It is hard to remember this was once a place of despair brought on by a cruel combination of nature and economic forces at their most terrifying.

This was a bleak and hostile land in the Dirty Thirties.

Families struggled against drought, grasshoppers, collapsed markets, and fear. Billowing clouds of topsoil, lifted off the land by fierce winds, reduced the sun to a faint orb; in April 1934, traces of Great Plains soil were found as far east as Washington, D.C. One report said the dust storm was so bad it left a film on President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Oval Office desk.

This is where my mother and father were raised and came of age, at the height of the Depression. It is where I was born and spent the first twenty-two years of my life, and it remains always familiar, however long I have been away. Whenever I return, I try to imagine the struggles my parents and everyone else went through here in the thirties. That time formed them-and through them, it formed me. I am in awe of how they emerged, and I am grateful for their legacy, although I have been an imperfect steward.

I left in 1962, hungry for bright lights, big cities, big ideas, and exotic places well beyond the conventions and constraints of my small-town childhood, but forty years later I still call South Dakota home. Time and distance have sharpened my understanding of the forces that shaped my parents' lives and mine so enduringly. Those forces are the grid on which I've come to rely, in good times and bad.

In the late 1800s, the Dakota Territory was one of the last frontiers in America, a broad, flat grassland where Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and their followers in the Sioux nation were hunters and warriors on horseback, determined to hold their land against the persistent invasion of white settlers who wanted to farm, ranch, and build towns along the railroad lines racing westward from the industrialized East and Midwest.

The Sioux won some battles, notably Little Big Horn in Montana, but they lost the war. The Dakota Territory was divided into two states, one north and one south, in 1889. My ancestors were among the early settlers in what became South Dakota.

My father, Anthony Orville Brokaw, was born on October 17, 1912, the last of ten children of William and Elizabeth Brokaw. His grandfather Richard P. Brokaw, the descendant of Huguenots who immigrated early to New York, had made his way to the southwestern Dakota Territory by covered wagon following the Civil War. He farmed and worked on the railroad before heading north in 1881 to found the town of Bristol and a small hotel, the Brokaw House, at the planned intersection of the north-south and east-west rail lines, eight years before statehood.

My mother is the eldest daughter of Jim and Ethel Conley, who farmed south of Bristol. Ethel took the train from Bristol to Minneapolis, her hometown, for Jean's birth; then mother and daughter returned to the remote corner of the prairie where Jim was tilling the ground behind teams of horses.

In the summer of 1996 my mother and I returned to the northern plains, the womb of her life and mine, for a visit that was at once nostalgic, reassuring, and a commentary on the social and economic changes in this country in the second half of the twentieth century.

As we drove east along Highway 212 from Aberdeen, South Dakota, toward Bristol, we passed a giant Wal-Mart with a parking lot full of late-model cars and pickup trucks; there were expensive new houses on large lots, and broad streets well beyond the city limits; giant John Deere combines, worth more than $100,000 apiece, moved efficiently through ripe fields of wheat, disgorging the small, valuable kernels into a truck of the kind called a Twin Hopper for its side-by-side bins that can hold a combined total of one thousand bushels. Many of the combines have air-conditioning and stereos in their cabs, to go with the computer monitoring systems that record the yield while the harvest is under way. Many of the smaller farms have been consolidated into larger tracts and organized as corporations with sophisticated business models relying on the efficiencies of mass production and the yield of genetically engineered grains. Much has changed, but still, a drought or a sudden hailstorm or a freak cold snap can undo all of the best planning and agriculture science.

Modern technology hasn't completely eliminated what my mother remembers of the sweat and heartache required for a farmer's life. But it is a far different world than when I was a child. As a town kid, I was attracted to the farm only by the prospect of a horseback ride or the chance to drive a tractor. I had no inclination for the work, much of it unending and involving uncooperative livestock in a muck of mud and manure or working in fields beneath a blazing sun.

South Dakota is two states, really, divided by the Missouri River. In a larger sense, the river also divides the Midwest from the Far West. East of the Missouri, in the midwestern half, small towns shaded by trees planted a hundred years ago are separated by clusters of farm buildings and quadrangles of tilled ground producing corn, soybeans, wheat, rye, and sunflowers.

As you move across the Missouri, into what we call West River country, the change is abrupt. On airplanes flying across South Dakota east to west, I like to tell my fellow passengers to watch the cultivated fields, the gold and green color schemes of corn and wheat, suddenly give way to the muted browns and the untilled sod once we cross the river. It is such a stunning change, it is as if someone flipped a page, and then another change comes two hundred miles farther. At the very western edge of the state, the prairie breaks up into the arid and eerily beautiful Badlands and then gives way to the Black Hills, a small scenic mountain range the Sioux people called Paha Sapa, the most sacred of their land.

I have lived and traveled in every quarter of the state, and I am constantly struck by the rawness of it all, even now, more than 125 years after the first significant wave of white settlers began trying to tame it. Even a summer night in a substantial dwelling in an established town can be a reminder of the primal forces of the old Dakota Territory when a storm blows up, filling the sky with mountainous thunderstorms and bowing the tall cottonwoods with cold winds that seem to begin somewhere near the Arctic Circle.

I am particularly attached to the Missouri River, that ancient artery that begins in central Montana and powers its way north before beginning its long east-by-southeast trek across the flat landscape of the Dakotas and along the borders of Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri. Large dams have slowed but not completely conquered the river of Lewis and Clark, the Sioux, the Crow, Omaha, and Santee tribes. Whenever I return to my home state I always try to swim in the river channel, just to feel its restless currents again, as a reminder of my early struggles to master them as a beginning swimmer. They taught me to understand force and use it to my advantage, taught me that to make progress often means giving a little.

On this trip back to Bristol with my mother in 1996, as I steered our rental car toward the distant eastern horizon, an old sensation returned. Up there in the northern latitudes, less than two hundred miles from the Canadian border, I feel as if I am riding the curvature of the earth, silhouetted against the sweeping arc of sky that so diminishes all below. I have now lived two thirds of my life outside these familiar surroundings, yet whenever I return I am at peace, and always a little excited to know that this place has a claim on me.

I am named for my maternal great-grandfather Thomas Conley, the son of Irish immigrants, who was working as a railroad conductor in St. Paul when he was attracted by the abundance of affordable farmland in Day County, South Dakota. Tom and his wife, Mathilda, moved in 1897 to Webster, the Day County seat, where Tom opened a saloon before moving on to a section and a half of prairie, 960 acres, southwest of Bristol, where together he and Mathilda began farming with horse-drawn machinery.

Tom Conley, at six feet a tall man in those days, quickly established a reputation as a hardworking and efficient farmer who, according to local lore, took off only one day a year: the Fourth of July. On Independence Day he'd drive a horse-drawn wagon from the farm to Bristol's main street for the celebrations, shouting to everyone, "Hurray for the Fourth of July!"

Tom and Mathilda Conley prospered in the early days of the twentieth century, sending three of their four sons to college. One went on to law school and another to medical school. My mother's father, Jim, graduated from a pharmacy college in Minneapolis, but he preferred farming to pharmacy and returned to Day County with his bride, Ethel Baker, a handsome and lively daughter of a foreman at Pillsbury Mills in the Twin Cities. As a wedding present, Tom Conley gave his son and new wife as a wedding present a mortgaged quarter-section, 160 treeless acres just north of his farm. It was so barren that Jim Conley often said it contained not even a rusty nail; black-and-white pictures from that time are startling in their bleakness.

A quarter-section of land was the allotment that the seminal figure of prairie literature, Per Hansa, filed for when he took his family into the Dakota Territory, in O. E. Rolvaag's classic Giants in the Earth. Powerful winds, broad horizons, "And sun! And still more sun!"-as Rolvaag vividly described this part of America that stretches from the Canadian border to Oklahoma, from Minnesota to the middle of Montana.

It was little changed in the first quarter of the twentieth century, when my parents were youngsters. Just as for Per Hansa and his fellow Norwegian settlers, it was a demanding place, whatever the season, for those who came to farm or to establish the small towns where agriculture and commerce intersected across the grassland. It is a place that reflects a century of transformation in America.

When my mother was born, in November 1917, the world was in turmoil. That same month Lenin took control of the Russian government and the Communist revolution was under way. America entered World War I at last, and General John Pershing led American forces into Europe. The war was an international tragedy but a bonanza for American farmers, as they moved into mechanized equipment and turned their grain fields into the bread basket of the world. Farmland in the heart of the corn belt brought prices two and three times what they had been just three years earlier.

Jim and Ethel were making enough money to start a new home and buy a Model T, the little black car that was the centerpiece of Henry Ford's rapidly growing empire. Neither of my grandparents left behind a personal account of their hopes and dreams, but I suspect they thought the farm would become their life work. Instead, it became a heartbreaking burden.

By 1930 they were trapped between a prolonged drought across the Great Plains and economic chaos in the international markets. Jim and Ethel, my mother, Jean, and her younger sister, Marcia, were hostage to the cruelties of what came to be known as the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1932, the average net per capita income on family farms fell from $2,297 to $74.

Jim Conley admired Herbert Hoover, a native of nearby Iowa and a brilliant mining engineer who was an international hero for his organization of food programs for Europe following the devastation of World War I. It is likely that Jim voted for Hoover in the 1928 presidential election. But what happened in the thirties would make my grandfather an ardent Democrat for his remaining days.

Jim and Ethel Conley's hopes for a long life on the farm were wiped out. By 1932, Jim was feeding his corn crop to his hogs because doing so was more economical than taking it to market, where it would have brought less than a nickel a bushel. By my mother's junior year in high school, the Conley farm days were over. The bank foreclosed and the family moved to nearby Bristol.

Because my parents came of age during the Great Depression, it never completely left their consciousness. It would be too melodramatic to say they carried lasting scars, but it would be equally inaccurate to describe the Depression as just a benign passage in their lives. The residual effect went well beyond the bleak economics of the time. Living through the Great Depression formed other lasting values: an unalloyed work ethic, thrift, compassion, and, perhaps most important, perspective.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“[A] love letter to the...people and places that enriched a ‘Tom Sawyer boyhood.’ Brokaw...has a knack for delivering quirky observations on small-town life....Bottom line: Tom’s terrific.”

—People

“Breezy and straightforward...much like the assertive TV newsman himself.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Brokaw writes with disarming honesty.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Brokaw evokes a sense of community, a pride of citizenship, and a confidence in American ideals that will impress his readers.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

—People

“Breezy and straightforward...much like the assertive TV newsman himself.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Brokaw writes with disarming honesty.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Brokaw evokes a sense of community, a pride of citizenship, and a confidence in American ideals that will impress his readers.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

Descriere

Reflections on America and the American experience as he has lived and observed it, by the bestselling author of "The Greatest Generation."

Premii

- Audies Finalist, 2004