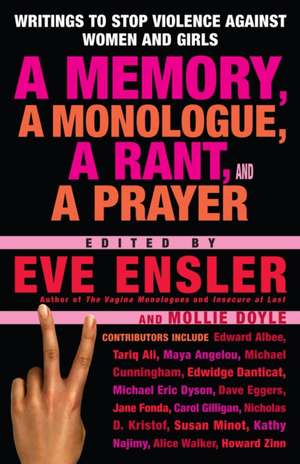

A Memory, a Monologue, a Rant, and a Prayer

Edward Albee Editat de Eve Ensler, Mollie Doyleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2007

Featuring writings by Abiola Abrams • Edward Albee • Tariq Ali • Maya Angelou • Periel Aschenbrand • Patricia Bosworth • Nicole Burdette • Kate Clinton • Kimberle Crenshaw • Michael Cunningham • Edwidge Danticat • Ariel Dorfman • Mollie Doyle • Slavenka Drakulic • Michael Eric Dyson • Dave Eggers • Kathy Engel • Eve Ensler • Jane Fonda • Carol Gilligan • Jyllian Gunther • Suheir Hammad • Christine House • Marie Howe • Carol Michèle Kaplan • Moisés Kaufman • Michael Klein • Nicholas Kristof • James Lecesne • Elizabeth Lesser • Mark Matousek • Deena Metzger • Susan Miller • Winter Miller • Susan Minot • Robin Morgan • Kathy Najimy • Lynn Nottage • Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy • Sharon Olds • Hanan al-Shaykh • Anna Deavere Smith • Diana Son • Monica Szlekovics • Robert Thurman • Betty Gale Tyson • Alice Walker • Jody Williams • Erin Cressida Wilson • Howard Zinn

This groundbreaking collection, edited by author and playwright Eve Ensler, features pieces from “Until the Violence Stops,” the international tour that brings the issue of violence against women and girls to the forefront of our consciousness. These diverse voices rise up in a collective roar to break open, expose, and examine the insidiousness of brutality, neglect, a punch, or a put-down. Here is Edward Albee on S&M; Maya Angelou on women’s work; Michael Cunningham on self-mutilation; Dave Eggers on a Sudanese

abduction; Carol Gilligan on a daughter witnessing her mother being hit; Susan Miller on raising a son as a single mother; and Sharon Olds on a bra.

These writings are inspired, funny, angry, heartfelt, tragic, and beautiful. But above all, together they create a true and profound portrait of this issue’s effect on every one of us. With information on how to organize an “Until the Violence Stops” event in your community, A Memory, a Monologue, a Rant, and a Prayer is a call to the world to demand an end to violence against women.

“In the current era, it takes some brain racking to think of anyone else doing anything quite like Ensler. She’s a countercultural consciousness-raiser, an empowering figure, a truth-teller.”

–Chicago Tribune

Preț: 106.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 159

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.33€ • 21.30$ • 16.80£

20.33€ • 21.30$ • 16.80£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 11-25 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345497918

ISBN-10: 0345497910

Pagini: 223

Dimensiuni: 168 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Villard Books

ISBN-10: 0345497910

Pagini: 223

Dimensiuni: 168 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Villard Books

Extras

Looking for the Body Music

Michael Klein

My friend Frank calls it looking for the body music—the music my mother heard.

At the end of looking for the body music, one stumbles upon a woman’s body

with the whole world taken out of her—but before that scene,

a foreshadow: my mother at the boarding school.

She’s twelve, child of two alcoholics, vaudevillians, shadows on a stage.

She’s overweight and sees beyond herself even then, so the girls

are mean in their pressed dresses and routinely hang my mother out

the window by her feet for a long time waiting for the exactly right cadence of please before they pull her back into her life.

That was in 1940-something—the year my mother began

the book her mind was writing called this is what happened to me—

the book she read to us—pill-language to cushion the abyss of two marriages—

one husband beat her up, one husband took her money and broke her off

with the world until she got written as the failed suicide after hanging by a thread

by a hair, by her feet, borne of her fierce suspension

over something called a youth.

7 Variations on Margarita Weinberg

Moisés Kaufman

Dedicated to the memory of Rebeca Clisci Akerman

1.

My grandmother was born in the Ukraine but immigrated to Venezuela before the Second World War. She told me this story:

A young Jewish woman was kidnapped by a group of Cossacks during a pogrom. They brought her into a room and held her down, deciding who would have her first.

“If you touch me I will put a curse on you,” the woman said. “I am a witch.” The Cossacks laughed. “I can prove it!” she shouted. “I can prove to you that I’m a witch.”

Their leader smiled and said, “Very well. Prove it, then.”

“I am immortal,” she said, “and you cannot kill me.” They laughed some more. “You cannot kill me. Not even if you shoot me. Try it.”

They stopped laughing and looked at her.

“Here. Try it.” She pointed to her chest. “Shoot me right here. You will see that I’m immortal.” The Cossacks looked at one another but didn’t move.

“Shoot me in the heart. You will see I won’t die. And then you’ll have your proof that I’m a witch.” The leader thought for a moment, then quickly took out his pistol and shot her in the heart. The young woman fell to the floor bleeding, looked at the man who had shot her, and said, “Thank you, you imbecile.”

My grandmother liked stories of heroic suicides.

2.

My grandmother wanted to be a doctor when she was young. But in the Ukraine in 1935, there were only a few seats at the university allotted to Jews, and all of them went to men. So she became a nurse.

When she told her family in 1937 that she wanted to go to Venezuela, everyone was against it. They hardly knew where Venezuela was on the map.

But her fiancé, Boris (my grandfather), had moved here two years earlier to make his fortune, and he wanted her to come join him; business was going well for him and he was worried about rumors of a war in Europe.

I don’t know if it was the imminent war or the invitation of a lover in the tropics, or both, but she came here. She was twenty-two years old.

The story goes that when she arrived in Caracas, she was a woman of such delicate beauty, every immigrant wanted to marry her. (I’ve seen pictures, and she was stunning.) And my grandfather said, “Although I brought you here, you have no obligation to marry me. We’ve been apart for two years, and your feelings might have changed. You can have your pick of any man in our community.”

My grandmother cried, moved by his words, and told him that yes, it was her decision. And her decision was to marry him. (Another version of the story is that their marriage had been arranged by their parents in the Ukraine, and that his asking her to choose to marry him was a testament to his liberal views, so she married him.)

3.

When their first child was born, my grandmother named her Margarita, which is the name of Venezuela’s national flower. Margarita Weinberg. (Her Jewish name, Miriam, came from my grandmother’s mother, who had died when my grandmother was two.)

My grandmother was the storyteller in the family.

In some arrangement made long before I was born, she had inherited the responsibility of keeping our narratives and our history alive for us.

“My brother was a Communist who left our village in the Ukraine and went to Paris to join the Resistance fighters against the Nazis,” she said. “He became one of their best spies. A street in Paris is named after him.” Two years after he joined the Resistance, he was surprised on a mission inside a German arsenal in a suburb of Paris. “When the Nazis surrounded the arsenal, he used all the weapons in it to defend himself. He killed many Nazis that day,” she told us. “He saved the last bullet for himself.”

Heroic suicides . . .

I grew up with these narratives.

4.

At nineteen my mother, Margarita, met a young man named Simon, who’d arrived in Venezuela after the war, from Romania. He’d survived the war by sewing and selling the yellow Stars of David that the Jews were made to wear. He spent most of the war alternately hiding in a small room and selling Stars of David. He was eleven.

My mother’s childhood in Venezuela was idyllic. The country was blessed with warm weather and kind inhabitants who were welcoming to the immigrants. The war was an ocean away, and my mother heard about it only when my grandparents would talk in hushed tones about relatives who had stayed behind and were now either in concentration camps or dead.

Simon was brought to Venezuela by his aunt, who had a successful clock shop in the center of town. She brought him to my grandmother’s house to meet my mother. They went out on a few dates, and then he asked her to marry him.

She liked him, but her intuition told her she shouldn’t marry him—he came from such a different life. She had never known hunger or war, except in the heroic and suicidal stories of her mother.

But my grandfather Boris said, “Do you think there’s a line of men waiting for you? We are a small Jewish community here. He’s a good man. You should marry him.”

My grandmother heard this but said nothing. And my mother married him.

Her strongest memory of her wedding day is standing under the canopy in the synagogue thinking, “What am I doing here? This feels like suicide.”

5.

Their marriage was a disaster. My mother’s intuition about Simon, my father, was absolutely correct. They were from two different worlds.

My father’s Eastern European upbringing, already stern and strict, had then been further hardened by the war. He loved Spi- noza, Schopenhauer, and other severe European philosophers. He was despotic and had little patience for things other than survival. His main interests were making a living, having children, and attending synagogue.

My mother loved American movies and Venezuelan balladeers and porcelain dolls. He was punctual and Germanic in his daily habits. She had the punctuality of people in the tropics and their laid-back attitude. He perceived her as spoiled and lazy. And his inability to understand her quickly turned to fury.

For her part, she often thought herself superior to him. The war had left deep scars: His manners were lacking or nonexistent; he laughed too loudly, spoke broken Spanish, and ate voraciously. (He told me he had been hungry for so long that he thought one could never have enough food to be satiated.)

6.

Every Friday night there would be a Sabbath dinner at our house. My clearest memory of those dinners was my father’s bright red face and the swollen veins in his neck as he yelled accusations. “The Sabbath candles were not lit at the right time! You don’t care about the Sabbath! What kind of a mother are you? This food is terrible! You don’t know how to cook! The children are too loud, what have you taught them?” Each attack was louder than the last: the shouting, the insults.

And yet every time my mother tried to answer him, my grandfather would say, “Margarita, let it be. Shoin.” (“Enough” in Yiddish.) And he wouldn’t let her respond. If my mother tried again, he would again say “Shoin,” and silence her.

Perhaps he thought this the best way to diffuse the argument, perhaps he himself was afraid of my father, perhaps he felt pity for him. Whatever the reason, my mother was always the one encouraged to silence. “Let him have his way,” my grandfather would tell her. “Who cares?”

But the most striking thing to me, even as a young boy, was that my grandmother would watch and listen and never say a word.

Margarita was being savagely attacked by my father and silenced by my grandfather and my grandmother said nothing—not a word.

7.

I thought my grandmother was heroic. She had to be, to cross the Atlantic, to settle in a small Latin American village without knowing the language, to raise three children in this new land, and to bear the responsibility of keeping our narratives alive.

But what good are narratives if they lead to suicide?

How could she stand by and watch her daughter be assaulted and do nothing? Did she think the harassment would end? Did she not realize that my mother needed her mother to defend her?

My mother thought of suicide many times. But she had three children. That’s the trouble with heroic stories . . .

My grandmother passed away seven years ago, and since then another tacit agreement has made me the writer in the family, the keeper of our stories. Members of my family come to me to ask about the past.

And so in writing this story I call my mother to make sure I’ve gotten it right. And I take the opportunity to ask her about these events. “Did you ever ask your mother why she didn’t defend you?”

“I was an adult. I had three children. It was not for her to defend me,” she tells me. “And I think you have part of the story wrong.”

She tells me a different version of my grandmother’s arrival in Venezuela, one she heard from her aunt.

In this version, after my grandfather left the Ukraine to come to Venezuela, my grandmother fell madly in love with a revolutionary Communist. Her father forbade the affair, and the Communist lover, brokenhearted, went to Spain to fight in the civil war. There he was killed in battle. Her father, keenly aware of the imminent war in Europe, forced my grandmother to go to Venezuela and marry my grandfather.

If this version is true, my grandmother’s heroic tales served a deeper purpose than I had originally imagined. They weren’t a code of conduct, or a commitment to revolt; they were simply the longings of an adolescent Ukrainian girl living in the tropics. Heroic actions that she could fantasize about but never act upon.

The real lesson she had learned from her father was: Compromise to survive.

The heroine in my grandmother’s pogrom story might have survived had she compromised. Her brother would have been captured and maybe even lived a few more years had he not used the bullet on himself. But they decided against it.

These stories were the road not taken. The life not lived.

And hence she could dream them, but she could not really teach her daughter how to act on them.

Suicide was good in fiction. Not good in reality. In reality silence and obedience seemed to secure survival.

And heroism was a virtue to admire in a novel or a trans- atlantic journey. But not a recipe for life . . .

My mother eventually divorced my father, then married him again and divorced him again. That was ten years ago.

“I’m glad you’re writing this down,” she tells me. “It certainly doesn’t have the flair of your grandmother stories.” She smiles. “It took me a long time and many rewrites, but I finally left your father. And I’m satisfied with that outcome”—she pauses—“and that it didn’t end in suicide.”

Michael Klein

My friend Frank calls it looking for the body music—the music my mother heard.

At the end of looking for the body music, one stumbles upon a woman’s body

with the whole world taken out of her—but before that scene,

a foreshadow: my mother at the boarding school.

She’s twelve, child of two alcoholics, vaudevillians, shadows on a stage.

She’s overweight and sees beyond herself even then, so the girls

are mean in their pressed dresses and routinely hang my mother out

the window by her feet for a long time waiting for the exactly right cadence of please before they pull her back into her life.

That was in 1940-something—the year my mother began

the book her mind was writing called this is what happened to me—

the book she read to us—pill-language to cushion the abyss of two marriages—

one husband beat her up, one husband took her money and broke her off

with the world until she got written as the failed suicide after hanging by a thread

by a hair, by her feet, borne of her fierce suspension

over something called a youth.

7 Variations on Margarita Weinberg

Moisés Kaufman

Dedicated to the memory of Rebeca Clisci Akerman

1.

My grandmother was born in the Ukraine but immigrated to Venezuela before the Second World War. She told me this story:

A young Jewish woman was kidnapped by a group of Cossacks during a pogrom. They brought her into a room and held her down, deciding who would have her first.

“If you touch me I will put a curse on you,” the woman said. “I am a witch.” The Cossacks laughed. “I can prove it!” she shouted. “I can prove to you that I’m a witch.”

Their leader smiled and said, “Very well. Prove it, then.”

“I am immortal,” she said, “and you cannot kill me.” They laughed some more. “You cannot kill me. Not even if you shoot me. Try it.”

They stopped laughing and looked at her.

“Here. Try it.” She pointed to her chest. “Shoot me right here. You will see that I’m immortal.” The Cossacks looked at one another but didn’t move.

“Shoot me in the heart. You will see I won’t die. And then you’ll have your proof that I’m a witch.” The leader thought for a moment, then quickly took out his pistol and shot her in the heart. The young woman fell to the floor bleeding, looked at the man who had shot her, and said, “Thank you, you imbecile.”

My grandmother liked stories of heroic suicides.

2.

My grandmother wanted to be a doctor when she was young. But in the Ukraine in 1935, there were only a few seats at the university allotted to Jews, and all of them went to men. So she became a nurse.

When she told her family in 1937 that she wanted to go to Venezuela, everyone was against it. They hardly knew where Venezuela was on the map.

But her fiancé, Boris (my grandfather), had moved here two years earlier to make his fortune, and he wanted her to come join him; business was going well for him and he was worried about rumors of a war in Europe.

I don’t know if it was the imminent war or the invitation of a lover in the tropics, or both, but she came here. She was twenty-two years old.

The story goes that when she arrived in Caracas, she was a woman of such delicate beauty, every immigrant wanted to marry her. (I’ve seen pictures, and she was stunning.) And my grandfather said, “Although I brought you here, you have no obligation to marry me. We’ve been apart for two years, and your feelings might have changed. You can have your pick of any man in our community.”

My grandmother cried, moved by his words, and told him that yes, it was her decision. And her decision was to marry him. (Another version of the story is that their marriage had been arranged by their parents in the Ukraine, and that his asking her to choose to marry him was a testament to his liberal views, so she married him.)

3.

When their first child was born, my grandmother named her Margarita, which is the name of Venezuela’s national flower. Margarita Weinberg. (Her Jewish name, Miriam, came from my grandmother’s mother, who had died when my grandmother was two.)

My grandmother was the storyteller in the family.

In some arrangement made long before I was born, she had inherited the responsibility of keeping our narratives and our history alive for us.

“My brother was a Communist who left our village in the Ukraine and went to Paris to join the Resistance fighters against the Nazis,” she said. “He became one of their best spies. A street in Paris is named after him.” Two years after he joined the Resistance, he was surprised on a mission inside a German arsenal in a suburb of Paris. “When the Nazis surrounded the arsenal, he used all the weapons in it to defend himself. He killed many Nazis that day,” she told us. “He saved the last bullet for himself.”

Heroic suicides . . .

I grew up with these narratives.

4.

At nineteen my mother, Margarita, met a young man named Simon, who’d arrived in Venezuela after the war, from Romania. He’d survived the war by sewing and selling the yellow Stars of David that the Jews were made to wear. He spent most of the war alternately hiding in a small room and selling Stars of David. He was eleven.

My mother’s childhood in Venezuela was idyllic. The country was blessed with warm weather and kind inhabitants who were welcoming to the immigrants. The war was an ocean away, and my mother heard about it only when my grandparents would talk in hushed tones about relatives who had stayed behind and were now either in concentration camps or dead.

Simon was brought to Venezuela by his aunt, who had a successful clock shop in the center of town. She brought him to my grandmother’s house to meet my mother. They went out on a few dates, and then he asked her to marry him.

She liked him, but her intuition told her she shouldn’t marry him—he came from such a different life. She had never known hunger or war, except in the heroic and suicidal stories of her mother.

But my grandfather Boris said, “Do you think there’s a line of men waiting for you? We are a small Jewish community here. He’s a good man. You should marry him.”

My grandmother heard this but said nothing. And my mother married him.

Her strongest memory of her wedding day is standing under the canopy in the synagogue thinking, “What am I doing here? This feels like suicide.”

5.

Their marriage was a disaster. My mother’s intuition about Simon, my father, was absolutely correct. They were from two different worlds.

My father’s Eastern European upbringing, already stern and strict, had then been further hardened by the war. He loved Spi- noza, Schopenhauer, and other severe European philosophers. He was despotic and had little patience for things other than survival. His main interests were making a living, having children, and attending synagogue.

My mother loved American movies and Venezuelan balladeers and porcelain dolls. He was punctual and Germanic in his daily habits. She had the punctuality of people in the tropics and their laid-back attitude. He perceived her as spoiled and lazy. And his inability to understand her quickly turned to fury.

For her part, she often thought herself superior to him. The war had left deep scars: His manners were lacking or nonexistent; he laughed too loudly, spoke broken Spanish, and ate voraciously. (He told me he had been hungry for so long that he thought one could never have enough food to be satiated.)

6.

Every Friday night there would be a Sabbath dinner at our house. My clearest memory of those dinners was my father’s bright red face and the swollen veins in his neck as he yelled accusations. “The Sabbath candles were not lit at the right time! You don’t care about the Sabbath! What kind of a mother are you? This food is terrible! You don’t know how to cook! The children are too loud, what have you taught them?” Each attack was louder than the last: the shouting, the insults.

And yet every time my mother tried to answer him, my grandfather would say, “Margarita, let it be. Shoin.” (“Enough” in Yiddish.) And he wouldn’t let her respond. If my mother tried again, he would again say “Shoin,” and silence her.

Perhaps he thought this the best way to diffuse the argument, perhaps he himself was afraid of my father, perhaps he felt pity for him. Whatever the reason, my mother was always the one encouraged to silence. “Let him have his way,” my grandfather would tell her. “Who cares?”

But the most striking thing to me, even as a young boy, was that my grandmother would watch and listen and never say a word.

Margarita was being savagely attacked by my father and silenced by my grandfather and my grandmother said nothing—not a word.

7.

I thought my grandmother was heroic. She had to be, to cross the Atlantic, to settle in a small Latin American village without knowing the language, to raise three children in this new land, and to bear the responsibility of keeping our narratives alive.

But what good are narratives if they lead to suicide?

How could she stand by and watch her daughter be assaulted and do nothing? Did she think the harassment would end? Did she not realize that my mother needed her mother to defend her?

My mother thought of suicide many times. But she had three children. That’s the trouble with heroic stories . . .

My grandmother passed away seven years ago, and since then another tacit agreement has made me the writer in the family, the keeper of our stories. Members of my family come to me to ask about the past.

And so in writing this story I call my mother to make sure I’ve gotten it right. And I take the opportunity to ask her about these events. “Did you ever ask your mother why she didn’t defend you?”

“I was an adult. I had three children. It was not for her to defend me,” she tells me. “And I think you have part of the story wrong.”

She tells me a different version of my grandmother’s arrival in Venezuela, one she heard from her aunt.

In this version, after my grandfather left the Ukraine to come to Venezuela, my grandmother fell madly in love with a revolutionary Communist. Her father forbade the affair, and the Communist lover, brokenhearted, went to Spain to fight in the civil war. There he was killed in battle. Her father, keenly aware of the imminent war in Europe, forced my grandmother to go to Venezuela and marry my grandfather.

If this version is true, my grandmother’s heroic tales served a deeper purpose than I had originally imagined. They weren’t a code of conduct, or a commitment to revolt; they were simply the longings of an adolescent Ukrainian girl living in the tropics. Heroic actions that she could fantasize about but never act upon.

The real lesson she had learned from her father was: Compromise to survive.

The heroine in my grandmother’s pogrom story might have survived had she compromised. Her brother would have been captured and maybe even lived a few more years had he not used the bullet on himself. But they decided against it.

These stories were the road not taken. The life not lived.

And hence she could dream them, but she could not really teach her daughter how to act on them.

Suicide was good in fiction. Not good in reality. In reality silence and obedience seemed to secure survival.

And heroism was a virtue to admire in a novel or a trans- atlantic journey. But not a recipe for life . . .

My mother eventually divorced my father, then married him again and divorced him again. That was ten years ago.

“I’m glad you’re writing this down,” she tells me. “It certainly doesn’t have the flair of your grandmother stories.” She smiles. “It took me a long time and many rewrites, but I finally left your father. And I’m satisfied with that outcome”—she pauses—“and that it didn’t end in suicide.”

Descriere

The author of "The Vagina Monologues" initiates a howl of protest about violence against women and girls in this impressive collection of original writings by such luminaries as Alice Walker, Michael Cunningham, Kathy Najimy, Jane Fonda, and Maya Angelou.

Notă biografică

Edited by Eve Ensler and Mollie Doyle