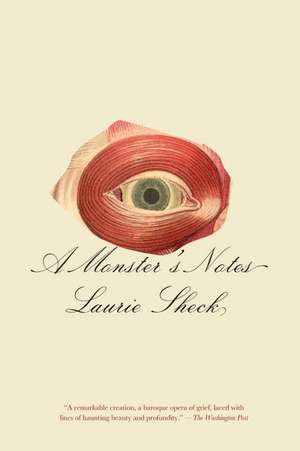

A Monster's Notes

Autor Laurie Shecken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2011

Now in paperback, the bold, genre-defying book that asked: What if Mary Shelley had not invented Frankenstein's monster at all but had met him when she was a girl of eight, sitting by her mother's grave, and he came to her unbidden?

In a riveting mix of fact and poetic license, Laurie Sheck gives us the "monster" in his own words: recalling how he was "made" and how Victor Frankenstein abandoned him; pondering the tragic tale of the Shelleys and the intertwining of his life with Mary's (whose fictionalized letters salt the narrative, along with those of her nineteenth-century intimates); taking notes on all aspects of human striving--from Gertrude Stein to robotics to the Northern explorers whose lonely quest mirrors his own--as he tries to understand the strange race that made yet shuns him, and to find his own freedom of mind.

Preț: 118.71 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 178

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.72€ • 23.63$ • 18.76£

22.72€ • 23.63$ • 18.76£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375711824

ISBN-10: 0375711821

Pagini: 530

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0375711821

Pagini: 530

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

Notă biografică

LAURIE SHECK is the author of five books of poetry, including The Willow Grove, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. A recent Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard and at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Boston Review, among other publications. She teaches in the MFA Program at the New School.

Extras

A LETTER

June 30, 2007

Dear Mr. Emilson,

This is to inform you that the final closing on your building on East 6th Street was successfully completed at 10:15 this morning. I have deposited the check as you instructed. The new owners will begin renovations tomorrow. In our previous communications, I asserted that the structure, now in great disrepair, was completely abandoned. However, yesterday afternoon as I made my last walk-through, I found on the second floor a short note, a manuscript wrapped in a rubber band, and an old computer. As these technically belong to you, please let me know if you want them forwarded to your London address. I have not unbound the manuscript, but reproduce for you here the short note left on top:

So much blurs …I write then forget what I write…walk these streets, a stranger to myself and others…Then sometimes it all suddenly flares back-my breath catches, my brain aches. How long have I wandered, talking in my thoughts to the one who made me from dead, discarded things, then left me? Why did he need to see me as frightful, misbegotten? I know he'll never hear, never answer.

Walking, I remember the other ones as well, those three I watched though none of them could see me. Isn't seeing a wounding and caressing both? All of them gone now, though once I held them with my secret eyes and in my own way loved them. Mary, Claire, Clerval… All those hours they visited me in air, came to me as voices made of flesh, ripe with shades of meaning, though in the end all that's left of them is absence.

Why did she need to portray me as she did? For so long I tried not to think of our days in the graveyard, the clicking of pebbles in her hands as she sat near the bushes, listening while I read. Even now the details grow faint…I try to forget…banish it all from my mind…though part of me wants only to remember. She was a child of nine sitting by her mother's grave. I sat behind the bushes with my books. Once we briefly spoke. Mostly I read to her, that's all. And her step-sister Claire, how strange that she came to me years later, long after I'd been wandering, heading North, far off in the Arctic by then. Why did she need to come to me, or was it I who needed her? And Clerval, that gentle man who everyone thought dead-in fact he traveled east as he'd wanted. Even now I sometimes picture his hand moving in gentle transcription as day after day he translated the Dream of The Red Chamber in his house at the foot of Xiangshan Hill, and wrote letters to his friend in Aosta.

Isn't any voice largely mute and partial, even those that speak openly and plainly (though of course I mostly hide). Why do I leave this? These words absorbed into the garbage dumps, the flames-

NOTES

NOTES ON THE EARTH SEEN FROM SPACE

Over and over the word fragile.“It looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart.” This from James Irwin, crew member of Apollo 15.

Astronaut Loren Acton spoke of seeing it “contained in the thin, moving, incredibly fragile shell of the biosphere.”

To Aleksei Leonov, the first man to walk in space, the earth looked “touchingly alone.” And when Vitali Sevastyanov was asked by ground control what he saw, he replied, “Half a world to the left, half a world to the right, I can see it all. The Earth is so small.”

Neil Armstrong said, “I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn't feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.”

And Ulf Merbold: “For the first time in my life I saw the horizon line as curved, accentuated by a thin seam of dark blue light. I was terrified by its fragile appearance.” (Is this what frightened you, is

this what you sought to combat and to flee? This fragility, this somehow-knowledge even then before

anyone had ever left the earth or seen it from a distance, of how small it is and delicate, as we are

too, how finite, how beside-the-point, how fleeting.)

(Might this partly account for my monstrous proportions, as if you were building a shield, a fortress

of flesh, as if the vertiginous wings of blood in us could somehow be made to tremble less. But I'm a blunt and narrow piece of materiality. Imprinting and imprinted. As were you. Footprints, strands of broken hair dropped here and there.)

On March 18, 1965, Alexei Leonov exited the main capsule of Voskohod2 by pushing himself head-first out of the opening. A 16-foot lifeline held him to the ship. If it broke he would drift off forever. Although the space-craft traveled at great speed, there was no air rushing past to let him feel it. He spun slowly for ten minutes. But when the co-pilot Belyayev told him to come back he didn't want to return.

(He didn't want to return. And yet it seems a lonely thing-that feeling of nothing pushing back.)

Several months later, Edward White walked in space for 20 minutes, though the term's deceptive as the motion is of free-fall or floating. Seen from 120 miles away, earth was nearly featureless. When he returned to the space ship he had lost 5 kg of body mass, and 2 kg of perspiration had collected in his boots.

But he, too, didn't want to return to the capsule.

When told to come back to the spacecraft he said, “This is the saddest moment of my life.”

His co-pilot pulled him back in.

(And you will work in sorrow the fields…As if your laboratory were a field, a wound always to be worked, a rivenness of mind needing to be healed. But when he floated there, in that region without weight or mass or shadow, all fields fell away, all shattering turned soft and pliant, there was no need anymore

either to build or to destroy-)

(But how my mind builds and destroys you over and over.)

On January 27, 1967, two years after his space walk, Edward White died in a fire on Launch Complex 34 at the Cape Canaveral Air Station. He had entered Apollo 1 for a simulated countdown along with Command Pilot Grissom and Pilot Roger Chaffee when the fire broke out.

Years later White's wife took her own life.

(How strange to see the earth from the sky and then come back…to float in space like that, barely tethered, earth a modest uncrowned thing. “So peaceful and so fragile,” one said of it. The size of a marble or a pearl “hanging delicately,” said another. And another: “But I did not see the Great Wall.” Still, there are many practicalities to be addressed (as you would have known even from your rudimentary laboratory). “It's a very sobering feeling to be up in space and realize one's safety factor's been determined by the lowest bidder on a government contract,” the astronaut Alan Shepherd pointed out.

And Neil Armstrong spoke of a feeling that was “complex, unforgiving.”

Lyndon Johnson said, “It's too bad, but the way the American people are, now that they have all this capability, instead of taking advantage of it, they'll probably just piss it away.”

(But what would it mean to take advantage?)

(And what of how small, and of how fragile…)

(Over and over the word fragile describing this world that has taught me such resistance, the hard of it

and brutal, and yet, still-)

Numerous inventions made for space have been adapted by private industry, resulting in studless snow tires, scratch proof eyeglasses (White needed to shield his eyes from the extreme glare of sunlight), the 5-year flashlight and cordless power hand tools.

The U.S. Space Walk of Fame Foundation was formed in the 1990's as a “major component of a redevelopment master plan designed for Titusville's urban waterfront.” There you can “visit the gift shop at the museum and treat yourself, a friend or a relative to a truly unique space-related gift.”

(When Leonov and White floated in space they didn't want to come back. They couldn't have known this beforehand. And what is a footstep then, after that, and the feeling of earth (so fragile, so small) beneath a shoe, or the thin tether of breath, or a name, or a day, a boundary, a theory, a bond-)

ICE DIARY

__________

I'm now far North. Archangel. Salt winds from the White Sea mix with naptha and lignite from the shipyards. Sea-ice cracks and groans, breaks on itself, breaks farther. So much whiteness violently dividing. Then stillness: ice locks in around the ships, seals them like footprints left in wax, or Pharoahs, mummy-wrapped, trapped and burning inward. For months each hull's a secret violently kept, volatile and cryptic. Shore lights flicker like something slowly starving.

If I still had a voice, if I could speak. But who would I speak to even then? These notes as if written in invisible ink. And the taste of blood in my mouth, or is it the memory of...And those bushes where I hid…

This morning I found a single stick ornamented with Chinese glass beads. Also a Kufan coin, a blurred list of provisions, a pair of oilskin breeches, a cap. A harsh quietness in them like the silence othose ice-locked hulls. Something helpless in them too, as if as they lay there in the ice they felt unremembered and remembering, unconnected yet somehow still connected-but to what? (Though of course I knew they could feel nothing.) Where did they come from-what lost ships?

But so many years since…And inflamed from blinding snow…And so far from…But I don't want to think about

that now…

Even this town's frozen-through. Stone walls still stand though most of what they guard's long vanished.

A few abandoned fortresses, a monastery, the mouth of the Northern Dvina nearby.

If I could see behind the shuttered windows-hands moving and changing even now-but I don't want to see such things again, want only to leave. It's said the more you draw toward true North the farther it recedes. There's no way to finally arrive. Still, I want to feel it.

This sting of salt. This shocked and changing emptiness of air. No trace of sea-birds, wolves. Slave built the canal here. Soon I will go farther.

__________

Lately when I close my eyes I see only this: a woman's white sleeve, her hand moving across a page, writing. The hand leaves steady markings in its wake-light chestnut-brown or black or darker brown. Sometimes it crosses out words, sometimes whole sentences, builds fences of x's, drops ink-stains on the page. Sometimes it turns the paper to the side, writes over and across words already left there. Or it halts as if netted, a sudden clenching of the tendons at the wrist. The first few times I could see little of the page but now that's changing.

Each night I wait for it-that white sleeve gathered at the wrist, that small determined hand. I read what it leaves:

Tonight I'm remembering Snow Hill. They called me Jane then, not Claire. Mother and Godwin never once called me Claire. Cold nights under flimsy blankets-as if that very name, Snow Hill, was seeping into the walls and through my bones. The square where the public executions were held stood barely 100 feet from our front door. The year we arrived (I was 9) they hung Haggerty and Halloway for the lavender merchant's murder. 28 people were trampled and suffocated in the crowd. Mary and I barely slept, thinking of that crush of feet like cattle's hooves, and all those faces suddenly unable to breathe, mouths useless holes. Afterwards I walked down the street alone, past the milliner shops, furriers, coffee dealers, wondering what strange creatures we are to inflict such things on ourselves. Minds contaminate themselves and actions grow ruinous. I feel this in myself-ruin prodigious and luxuriant as plant-life. It flourishes, this crumbling, this destruction, and yet there's also-

It was around that time I searched through Mother's things for my birth certificate. But it seems there's no record of my birth or baptism. Some say she was put in a debtor's prison shortly after I was born (so was I in that debtor's prison too?) then relieved and set free through a charitable subscription. A few years later she met Godwin. I've no name for my father. Maybe it's better this way.

Snow Hill-I still feel its coldness in my bones, and how after awhile I wanted only to leave. Though I loved the books on the shelves and sometimes the eyes that watched me, the eyes I watched back. How watching is a kindness and a shackling both. The chain of it, the net, the binding. And I remember, above the doorway, the stone face of Aesop reading.

_________

Sea-water ice holds my weight when I walk, but black ice is thin, can't be trusted. Sometimes I don't know which one I'm on. The wind's a fist in my mouth. I bend down, huddle on the ground, try only to breathe. Or I come back inside, say her name to myself: Claire. Air.

Why do I wait for her?-that hand and the walls of ink it builds and leaves.

Claire. Air. Care. Clear. Claire.

At first glance the hand's delicate, but I see now the finger-bones are strong. Lately she comes before I even close my eyes, that hand lingering in the air and writing. Forty degrees below, sixty degrees below. Her white nightdress thin, yet she seems to feel no cold.

Her face not visible to me. I never see her face.

From the Hardcover edition.

June 30, 2007

Dear Mr. Emilson,

This is to inform you that the final closing on your building on East 6th Street was successfully completed at 10:15 this morning. I have deposited the check as you instructed. The new owners will begin renovations tomorrow. In our previous communications, I asserted that the structure, now in great disrepair, was completely abandoned. However, yesterday afternoon as I made my last walk-through, I found on the second floor a short note, a manuscript wrapped in a rubber band, and an old computer. As these technically belong to you, please let me know if you want them forwarded to your London address. I have not unbound the manuscript, but reproduce for you here the short note left on top:

So much blurs …I write then forget what I write…walk these streets, a stranger to myself and others…Then sometimes it all suddenly flares back-my breath catches, my brain aches. How long have I wandered, talking in my thoughts to the one who made me from dead, discarded things, then left me? Why did he need to see me as frightful, misbegotten? I know he'll never hear, never answer.

Walking, I remember the other ones as well, those three I watched though none of them could see me. Isn't seeing a wounding and caressing both? All of them gone now, though once I held them with my secret eyes and in my own way loved them. Mary, Claire, Clerval… All those hours they visited me in air, came to me as voices made of flesh, ripe with shades of meaning, though in the end all that's left of them is absence.

Why did she need to portray me as she did? For so long I tried not to think of our days in the graveyard, the clicking of pebbles in her hands as she sat near the bushes, listening while I read. Even now the details grow faint…I try to forget…banish it all from my mind…though part of me wants only to remember. She was a child of nine sitting by her mother's grave. I sat behind the bushes with my books. Once we briefly spoke. Mostly I read to her, that's all. And her step-sister Claire, how strange that she came to me years later, long after I'd been wandering, heading North, far off in the Arctic by then. Why did she need to come to me, or was it I who needed her? And Clerval, that gentle man who everyone thought dead-in fact he traveled east as he'd wanted. Even now I sometimes picture his hand moving in gentle transcription as day after day he translated the Dream of The Red Chamber in his house at the foot of Xiangshan Hill, and wrote letters to his friend in Aosta.

Isn't any voice largely mute and partial, even those that speak openly and plainly (though of course I mostly hide). Why do I leave this? These words absorbed into the garbage dumps, the flames-

NOTES

NOTES ON THE EARTH SEEN FROM SPACE

Over and over the word fragile.“It looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart.” This from James Irwin, crew member of Apollo 15.

Astronaut Loren Acton spoke of seeing it “contained in the thin, moving, incredibly fragile shell of the biosphere.”

To Aleksei Leonov, the first man to walk in space, the earth looked “touchingly alone.” And when Vitali Sevastyanov was asked by ground control what he saw, he replied, “Half a world to the left, half a world to the right, I can see it all. The Earth is so small.”

Neil Armstrong said, “I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn't feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.”

And Ulf Merbold: “For the first time in my life I saw the horizon line as curved, accentuated by a thin seam of dark blue light. I was terrified by its fragile appearance.” (Is this what frightened you, is

this what you sought to combat and to flee? This fragility, this somehow-knowledge even then before

anyone had ever left the earth or seen it from a distance, of how small it is and delicate, as we are

too, how finite, how beside-the-point, how fleeting.)

(Might this partly account for my monstrous proportions, as if you were building a shield, a fortress

of flesh, as if the vertiginous wings of blood in us could somehow be made to tremble less. But I'm a blunt and narrow piece of materiality. Imprinting and imprinted. As were you. Footprints, strands of broken hair dropped here and there.)

On March 18, 1965, Alexei Leonov exited the main capsule of Voskohod2 by pushing himself head-first out of the opening. A 16-foot lifeline held him to the ship. If it broke he would drift off forever. Although the space-craft traveled at great speed, there was no air rushing past to let him feel it. He spun slowly for ten minutes. But when the co-pilot Belyayev told him to come back he didn't want to return.

(He didn't want to return. And yet it seems a lonely thing-that feeling of nothing pushing back.)

Several months later, Edward White walked in space for 20 minutes, though the term's deceptive as the motion is of free-fall or floating. Seen from 120 miles away, earth was nearly featureless. When he returned to the space ship he had lost 5 kg of body mass, and 2 kg of perspiration had collected in his boots.

But he, too, didn't want to return to the capsule.

When told to come back to the spacecraft he said, “This is the saddest moment of my life.”

His co-pilot pulled him back in.

(And you will work in sorrow the fields…As if your laboratory were a field, a wound always to be worked, a rivenness of mind needing to be healed. But when he floated there, in that region without weight or mass or shadow, all fields fell away, all shattering turned soft and pliant, there was no need anymore

either to build or to destroy-)

(But how my mind builds and destroys you over and over.)

On January 27, 1967, two years after his space walk, Edward White died in a fire on Launch Complex 34 at the Cape Canaveral Air Station. He had entered Apollo 1 for a simulated countdown along with Command Pilot Grissom and Pilot Roger Chaffee when the fire broke out.

Years later White's wife took her own life.

(How strange to see the earth from the sky and then come back…to float in space like that, barely tethered, earth a modest uncrowned thing. “So peaceful and so fragile,” one said of it. The size of a marble or a pearl “hanging delicately,” said another. And another: “But I did not see the Great Wall.” Still, there are many practicalities to be addressed (as you would have known even from your rudimentary laboratory). “It's a very sobering feeling to be up in space and realize one's safety factor's been determined by the lowest bidder on a government contract,” the astronaut Alan Shepherd pointed out.

And Neil Armstrong spoke of a feeling that was “complex, unforgiving.”

Lyndon Johnson said, “It's too bad, but the way the American people are, now that they have all this capability, instead of taking advantage of it, they'll probably just piss it away.”

(But what would it mean to take advantage?)

(And what of how small, and of how fragile…)

(Over and over the word fragile describing this world that has taught me such resistance, the hard of it

and brutal, and yet, still-)

Numerous inventions made for space have been adapted by private industry, resulting in studless snow tires, scratch proof eyeglasses (White needed to shield his eyes from the extreme glare of sunlight), the 5-year flashlight and cordless power hand tools.

The U.S. Space Walk of Fame Foundation was formed in the 1990's as a “major component of a redevelopment master plan designed for Titusville's urban waterfront.” There you can “visit the gift shop at the museum and treat yourself, a friend or a relative to a truly unique space-related gift.”

(When Leonov and White floated in space they didn't want to come back. They couldn't have known this beforehand. And what is a footstep then, after that, and the feeling of earth (so fragile, so small) beneath a shoe, or the thin tether of breath, or a name, or a day, a boundary, a theory, a bond-)

ICE DIARY

__________

I'm now far North. Archangel. Salt winds from the White Sea mix with naptha and lignite from the shipyards. Sea-ice cracks and groans, breaks on itself, breaks farther. So much whiteness violently dividing. Then stillness: ice locks in around the ships, seals them like footprints left in wax, or Pharoahs, mummy-wrapped, trapped and burning inward. For months each hull's a secret violently kept, volatile and cryptic. Shore lights flicker like something slowly starving.

If I still had a voice, if I could speak. But who would I speak to even then? These notes as if written in invisible ink. And the taste of blood in my mouth, or is it the memory of...And those bushes where I hid…

This morning I found a single stick ornamented with Chinese glass beads. Also a Kufan coin, a blurred list of provisions, a pair of oilskin breeches, a cap. A harsh quietness in them like the silence othose ice-locked hulls. Something helpless in them too, as if as they lay there in the ice they felt unremembered and remembering, unconnected yet somehow still connected-but to what? (Though of course I knew they could feel nothing.) Where did they come from-what lost ships?

But so many years since…And inflamed from blinding snow…And so far from…But I don't want to think about

that now…

Even this town's frozen-through. Stone walls still stand though most of what they guard's long vanished.

A few abandoned fortresses, a monastery, the mouth of the Northern Dvina nearby.

If I could see behind the shuttered windows-hands moving and changing even now-but I don't want to see such things again, want only to leave. It's said the more you draw toward true North the farther it recedes. There's no way to finally arrive. Still, I want to feel it.

This sting of salt. This shocked and changing emptiness of air. No trace of sea-birds, wolves. Slave built the canal here. Soon I will go farther.

__________

Lately when I close my eyes I see only this: a woman's white sleeve, her hand moving across a page, writing. The hand leaves steady markings in its wake-light chestnut-brown or black or darker brown. Sometimes it crosses out words, sometimes whole sentences, builds fences of x's, drops ink-stains on the page. Sometimes it turns the paper to the side, writes over and across words already left there. Or it halts as if netted, a sudden clenching of the tendons at the wrist. The first few times I could see little of the page but now that's changing.

Each night I wait for it-that white sleeve gathered at the wrist, that small determined hand. I read what it leaves:

Tonight I'm remembering Snow Hill. They called me Jane then, not Claire. Mother and Godwin never once called me Claire. Cold nights under flimsy blankets-as if that very name, Snow Hill, was seeping into the walls and through my bones. The square where the public executions were held stood barely 100 feet from our front door. The year we arrived (I was 9) they hung Haggerty and Halloway for the lavender merchant's murder. 28 people were trampled and suffocated in the crowd. Mary and I barely slept, thinking of that crush of feet like cattle's hooves, and all those faces suddenly unable to breathe, mouths useless holes. Afterwards I walked down the street alone, past the milliner shops, furriers, coffee dealers, wondering what strange creatures we are to inflict such things on ourselves. Minds contaminate themselves and actions grow ruinous. I feel this in myself-ruin prodigious and luxuriant as plant-life. It flourishes, this crumbling, this destruction, and yet there's also-

It was around that time I searched through Mother's things for my birth certificate. But it seems there's no record of my birth or baptism. Some say she was put in a debtor's prison shortly after I was born (so was I in that debtor's prison too?) then relieved and set free through a charitable subscription. A few years later she met Godwin. I've no name for my father. Maybe it's better this way.

Snow Hill-I still feel its coldness in my bones, and how after awhile I wanted only to leave. Though I loved the books on the shelves and sometimes the eyes that watched me, the eyes I watched back. How watching is a kindness and a shackling both. The chain of it, the net, the binding. And I remember, above the doorway, the stone face of Aesop reading.

_________

Sea-water ice holds my weight when I walk, but black ice is thin, can't be trusted. Sometimes I don't know which one I'm on. The wind's a fist in my mouth. I bend down, huddle on the ground, try only to breathe. Or I come back inside, say her name to myself: Claire. Air.

Why do I wait for her?-that hand and the walls of ink it builds and leaves.

Claire. Air. Care. Clear. Claire.

At first glance the hand's delicate, but I see now the finger-bones are strong. Lately she comes before I even close my eyes, that hand lingering in the air and writing. Forty degrees below, sixty degrees below. Her white nightdress thin, yet she seems to feel no cold.

Her face not visible to me. I never see her face.

From the Hardcover edition.