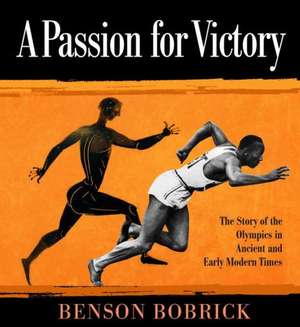

A Passion for Victory: The Story of the Olympics in Ancient and Early Modern Times

Autor Benson Bobricken Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 ian 2014 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Preț: 105.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.21€ • 21.16$ • 16.72£

20.21€ • 21.16$ • 16.72£

Cartea nu se mai tipărește

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375872525

ISBN-10: 0375872523

Pagini: 143

Dimensiuni: 201 x 231 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 0375872523

Pagini: 143

Dimensiuni: 201 x 231 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

BENSON BOBRICK earned his doctorate from Columbia University and is the author of one other nonfiction book for young people, The Battle of Nashville, and several critically acclaimed books for adults. In 2002, he received the Literature Award of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. He and his wife, Hilary, divide their time between New York and Vermont.

Extras

Chapter One

The Games Begin

Thousands of years ago, sports fans stood in stadiums like our own and cheered like crazy for the athletes they adored. One fan in the second century AD wrote to a friend, “Oh, I can’t describe the scene in mere words. You really should experience firsthand the incredible pleasure of standing in that cheering crowd, admiring the athletes’ courage and good looks, their amazing physical conditioning--their great skill and irresistible strength--all their bravery and their pride, their unbeatable determination, their unstoppable passion for victory! I know that if you were there in the stadium, you wouldn’t be able to stop applauding.”

He was talking about one of the ancient Olympic Games. By then, the Games were an established institution and had been occurring every four years without fail for almost a thousand years. For nearly that long, they had also been the rage of the Mediterranean world.

In addition to the Greeks, many ancient civilizations, including those in Egypt, Crete, and Celtic Ireland, incorporated athletic festivals or contests into their annual cycle of celebrations. But none kept going for as long as the Olympics have. Yet when the Olympics began, who could have imagined they would have such staying power? Their main purpose was to help hold widespread Greek communities together by a shared event.

In the eighth century BC, various Greek peoples had settled along the shores of the Mediterranean and adjacent seas. There were many differences between them, which eventually gave rise to rival city-states, like Athens and Sparta. But they had their “Greekness,” or Hellenic nature, in common. So the idea was to have a Panhellenic, or all-Greek, celebration that would affirm their common bond.

Only much later did the Games include representatives from other nationalities, and sportsmen from colonies as far away as Africa and Spain.

Over time, the Games also took on a life of their own. They remained communal but acquired the status of tradition. The determination to keep them going would outlast war, famine, turmoil, and even the conquest of Greece itself. They became a symbol of continuity amid the changing fate of nations and revolutions in world affairs.

Today, the Olympic Games are huge multicultural, multimedia events. They are global extravaganzas in which almost every nation takes part. Heroes of the Games enjoy enormous popularity and stature, and the principles the Olympics represent--athletic striving, fair play, goodwill among men--continue to excite the enthusiasm of sports fans throughout the world.

Yet the ancient Olympics could hardly have had a more humble start. As far as anyone knows, the first recorded Olympic event took place in 776 BC, when a 200-yard footrace was held in a meadow beside the Alpheus River in Olympia. The race was won by a man named Coroebus, from the nearby town of Elis, where he worked as a cook. Ideas for a local festival began to take hold, but for a dozen or so years the 200-yard footrace was the only Olympic contest. Then other races were added, drawing larger crowds. New events, too, joined the program, including the discus throw, the chariot race, the long jump, the javelin throw, wrestling, and boxing.

The footraces were of various lengths. The shortest, known as the stade, was a dash the length of the running track or stadium (hence its name), which at Olympia measured 200 yards. There was also a double stade race (up and down the track) and a 2 1/4-mile run twenty times around. As depicted in ancient art, the contestants were anything but lean or spare-looking, like some modern runners, but had substantial upper-body strength and bulging calves and thighs. “They evidently combined,” as one historian observes, “a driving knee action with a punching, piston-like movement of the arms for extra momentum.” Many sprinters, in fact, run like that today.

The footraces were run over a surface of layered sand and along a track with as many as twenty lanes. At the starting line, there was a stone slab into which grooves for toeholds were cut. As the runners took their places--in an order determined by lot--they warmed up for a few minutes, then (instead of going into a crouch like modern sprinters) stood up with their arms stretched forward, one foot slightly advanced. The blast of a herald’s trumpet sent them off. False starts were checked severely and offenders were struck by an official with his whip. Eventually (in the fourth century BC), the Greeks devised a starting mechanism known as the hysplex, which featured a series of starting gates released by strings.

The last of the race events (introduced in 520 BC) was unlike any other. It was more like a military field exercise than a race. Greek foot soldiers known as hoplites lined up and, at a signal, began to toil as best they could two times up and down the track in full body armor weighing about fifty pounds. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the event was meant to remind the public that the real point of athletic excellence was the development of martial strength and skill.

In those days, there was no record-keeping or timing of events, so there were no records to be broken or means to compare achievements from year to year. Each Olympics was a world of competition unto itself.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Games Begin

Thousands of years ago, sports fans stood in stadiums like our own and cheered like crazy for the athletes they adored. One fan in the second century AD wrote to a friend, “Oh, I can’t describe the scene in mere words. You really should experience firsthand the incredible pleasure of standing in that cheering crowd, admiring the athletes’ courage and good looks, their amazing physical conditioning--their great skill and irresistible strength--all their bravery and their pride, their unbeatable determination, their unstoppable passion for victory! I know that if you were there in the stadium, you wouldn’t be able to stop applauding.”

He was talking about one of the ancient Olympic Games. By then, the Games were an established institution and had been occurring every four years without fail for almost a thousand years. For nearly that long, they had also been the rage of the Mediterranean world.

In addition to the Greeks, many ancient civilizations, including those in Egypt, Crete, and Celtic Ireland, incorporated athletic festivals or contests into their annual cycle of celebrations. But none kept going for as long as the Olympics have. Yet when the Olympics began, who could have imagined they would have such staying power? Their main purpose was to help hold widespread Greek communities together by a shared event.

In the eighth century BC, various Greek peoples had settled along the shores of the Mediterranean and adjacent seas. There were many differences between them, which eventually gave rise to rival city-states, like Athens and Sparta. But they had their “Greekness,” or Hellenic nature, in common. So the idea was to have a Panhellenic, or all-Greek, celebration that would affirm their common bond.

Only much later did the Games include representatives from other nationalities, and sportsmen from colonies as far away as Africa and Spain.

Over time, the Games also took on a life of their own. They remained communal but acquired the status of tradition. The determination to keep them going would outlast war, famine, turmoil, and even the conquest of Greece itself. They became a symbol of continuity amid the changing fate of nations and revolutions in world affairs.

Today, the Olympic Games are huge multicultural, multimedia events. They are global extravaganzas in which almost every nation takes part. Heroes of the Games enjoy enormous popularity and stature, and the principles the Olympics represent--athletic striving, fair play, goodwill among men--continue to excite the enthusiasm of sports fans throughout the world.

Yet the ancient Olympics could hardly have had a more humble start. As far as anyone knows, the first recorded Olympic event took place in 776 BC, when a 200-yard footrace was held in a meadow beside the Alpheus River in Olympia. The race was won by a man named Coroebus, from the nearby town of Elis, where he worked as a cook. Ideas for a local festival began to take hold, but for a dozen or so years the 200-yard footrace was the only Olympic contest. Then other races were added, drawing larger crowds. New events, too, joined the program, including the discus throw, the chariot race, the long jump, the javelin throw, wrestling, and boxing.

The footraces were of various lengths. The shortest, known as the stade, was a dash the length of the running track or stadium (hence its name), which at Olympia measured 200 yards. There was also a double stade race (up and down the track) and a 2 1/4-mile run twenty times around. As depicted in ancient art, the contestants were anything but lean or spare-looking, like some modern runners, but had substantial upper-body strength and bulging calves and thighs. “They evidently combined,” as one historian observes, “a driving knee action with a punching, piston-like movement of the arms for extra momentum.” Many sprinters, in fact, run like that today.

The footraces were run over a surface of layered sand and along a track with as many as twenty lanes. At the starting line, there was a stone slab into which grooves for toeholds were cut. As the runners took their places--in an order determined by lot--they warmed up for a few minutes, then (instead of going into a crouch like modern sprinters) stood up with their arms stretched forward, one foot slightly advanced. The blast of a herald’s trumpet sent them off. False starts were checked severely and offenders were struck by an official with his whip. Eventually (in the fourth century BC), the Greeks devised a starting mechanism known as the hysplex, which featured a series of starting gates released by strings.

The last of the race events (introduced in 520 BC) was unlike any other. It was more like a military field exercise than a race. Greek foot soldiers known as hoplites lined up and, at a signal, began to toil as best they could two times up and down the track in full body armor weighing about fifty pounds. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the event was meant to remind the public that the real point of athletic excellence was the development of martial strength and skill.

In those days, there was no record-keeping or timing of events, so there were no records to be broken or means to compare achievements from year to year. Each Olympics was a world of competition unto itself.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Starred Review, Booklist, June 2012:

“Supported by loads of fascinating quotes, this history of the ancient and early modern Olympics shines.”

“Supported by loads of fascinating quotes, this history of the ancient and early modern Olympics shines.”