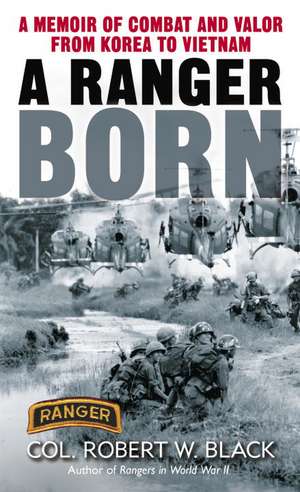

A Ranger Born: A Memoir of Combat and Valor from Korea to Vietnam: Ranger

Autor Robert W. Col. Blacken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2003

Born at the start of the Great Depression, Black grew up on a farm at a time of great hardship but also tremendous national determination. He was a kid who toughened up fast, who learned the hard way to rely on his strength and his wits, who saw the country go to war with Germany and Japan and wept because he was too young to serve. As soon as the army would take him, Black enlisted. And as soon as he could muscle his way in, he became a Ranger.

As a private first class in the 82d Airborne Division headquarters, Black withstood the humiliations of enlisted service in the peacetime brown-shoe army. When the Korean War began, he volunteered and trained to be an Airborne Ranger. In Korea, this young warrior, his mind and body bursting with the lusts of adolescence, grew up fast, literally in the line of fire. In clean, vivid prose, Black describes the hell of giving his all for a country that lacked the political resolve to give its all to a war against the North Koreans and the Chinese.

If Korea was frustrating, Vietnam was maddening. The heart of this book is devoted to the years of action that Black saw in Long An Province starting in 1967. Black writes of the perplexity of collaborating with South Vietnamese officers whose culture and motives he never fully understood; he conjures up the sudden shock of the Tet Offensive and the daily horror of seeing fellow soldiers and innocent civilians slaughtered—sometimes by stray bullets, often by carelessness or treachery. Vietnam challenged everything Black had come to believe in and left him totally unprepared for the hostility he would face when he returned to a war-weary America.

Written with extraordinary candor and passion, A Ranger Born is the memoir of a man who dedicated the best of his life to everything that is great and enduring about America. At once intimate in its revelations and universal in its themes, it is a book with profound relevance to our own troubled time in history.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 49.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.40€ • 9.71$ • 7.82£

9.40€ • 9.71$ • 7.82£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345453266

ISBN-10: 0345453263

Pagini: 366

Dimensiuni: 106 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Seria Ranger

ISBN-10: 0345453263

Pagini: 366

Dimensiuni: 106 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Seria Ranger

Notă biografică

Robert W. Black is a retired U.S. Army colonel who served in Vietnam and with the 8th Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne) in the Korean War. Parachute and glider qualified, twice the recipient of the combat Infantry Badge, he was awarded the Silver Star, three Bronze Stars—two for valor and one for meritorious service—the Legion of Merit, the Air Medal, and sixteen other awards and decorations. He was the founding president of the Airborne Ranger Association of the Korean War and was inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame in 1995. He is the author of Rangers in Korea and Rangers in World War II and is currently writing the definitive history of the Rangers over the past four hundred years and a book on Rangers in the American Civil War. He lives in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

A Ranger Young

All things have a beginning; mine was the fifteenth of June 1929. As soon as the United States learned of the event, it went into that cataclysmic period of despair known as the Great Depression.

I was the descendant of a long line of citizen warriors. On my mother's side, they came from Holland in the 1600s and settled in the area of Bergen County, New Jersey. Later they moved to New York City and intermarried with the Scots and the Welsh. My father's line was German. Coming through Philadelphia in 1713, they meandered through the Cumberland Valley, down the Shenandoah, and settled in the Yadkin River area of North Carolina. In the Revolutionary War, my ancestors fought the British and paid the price of freedom. One died in an infamous British prison called the Sugar House. Another was murdered by Loyalists when he came home from the Battle of Guilford Court House. In the Civil War, my great-grandfathers fought each other, the one from the North serving from Bull Run to Antietam. He was an engineer and while under fire laid a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River during the Battle of Fredericksburg. The one from the South was an infantryman and fought at the Battles of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Captured in 1865, he ended his military career as a prisoner of war. An uncle sailed around the world with Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet, and my father served in the navy in World War I and survived an attack on his ship by a German submarine. His ship, the USS Pocahontas, was homeported in New York, where he met my mother.

My mother was named Emma; she was my rock and I adored her. Brooklyn-born and raised in poverty, she was an angel who could curse like a trooper. Until age eight, I thought my name was "Ya goddamn dope!" but it was always followed by hugs and kisses.

I never heard my father say anything stronger than "cripes," but he was a hard and dangerous man. He was a crack shot, who as a boy kept fresh-killed meat on the family table. North Carolina relatives told us that when my father was in the third grade, he was badly beaten by a teacher. He went home, got a .22-caliber rifle, stood outside ringing the school bell with bullets, and called on the teacher to come out. The teacher went out a side window, and my father did not go back to school. He was quick with his temper and his fists. In later years I asked my uncle what my grandfather had been like. "Oh, he was a hard man," he responded, "knock ya flat as quick as look at ya." Perhaps it was inherited, as that description fit my father.

A college degree was rare in the early twentieth century. Sober, hardworking, and determined, my father had come far on a third-grade education and correspondence courses. His name was Frank Black. As the chief engineer of C. H. Masland's rug mill in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he felt mathematics was the only study worth pursuing. After dinner, his standard direction was "Get your nose in a book," meaning a thick book of fractions and equations. Years later, after his death at age eighty-five, I found that book in our family library. On a page therein scrawled in a childish hand was the inscription "Fuck you, Frank Black!" I hated math and became determined to live my life without it. Fortunately, my mother taught me to love other books. I would sneak away to enjoy Dumas and Sir Walter Scott. I doted on the gunfire and flashing swords of Rafael Sabatini's Captain Blood and Scaramouche.

My father loved the outdoors. In 1932, when there were fourteen men lined up for every job and many farms were for sale, he used his grand salary of fifty dollars a week to buy a farm. It consisted of 146 acres, located between the two historic Pennsylvania towns of Carlisle and Gettysburg. We lived in a big stone house that dated from the early 1800s. We had a wooden house nearby for tenants and a large Pennsylvania bank barn, which had been built in 1854 by experienced carpenters. The frame was made of great logs held together by thick wooden pegs.

I grew up in a wonderful outdoor life of woods, streams, and mountains. My bond with my father was hunting together. I was shooting from the age of nine. I also had ample opportunity to visit the Gettysburg battlefield, where my parents and I were present in 1938 for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the battle. My father told me it would be the last gathering of Civil War veterans. It was hard to believe that those old men had ever been young. We watched as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) dedicated the peace light. The battlefield fascinated me, and I discussed it with those adults who would share time with a child.

We had a tenant house. One of the renters was a combat infantryman, a sergeant from World War I. He talked with me of battles and on occasion allowed me to wear the steel helmet he had brought home. I listened with rapt attention when my father or "Old Sarge" would talk of wartime experiences.

My brother and sister were older, so they went to the higher-grade schools in Carlisle. I was dispatched to a one-room country schoolhouse where eight grades were taught in the same small room by the same teacher. The Depression had its grip on the nation and poverty was rampant.

This was a time when workingmen were told "Don't need ya." There was no unemployment compensation, and the pink slip in the final paycheck was a fearful thing. The adults called it "the crash" and "hard times." For many people it was a time of endless struggle, an era when idealism faced reality and died. My father said people were not interested in ideals, they wanted a job. He was not for Roosevelt; he said FDR would oppose an idea until it passed and then claim it as his own. That sounded very slick to me.

My loving mother sent me off to my first day in school wearing a white silk shirt and an outfit called "Little Lord Fauntleroy." I found my companions were farm boys who went barefoot spring, summer, and fall. Some wore Farmer Brown bib overalls without shirts. Many girls wore dresses made from the covering cloth of feed and flour sacks. The cloth was produced in simple prints to entice farm families to buy the product.

When they saw me, the country boys could hardly believe their good fortune. Now they had something more in their lives than endless arguments over whether a John Deere farm tractor was better than an Allis Chalmers. To most of these boys, tractors represented the ultimate wealth. The older boys were already manhandling plows in furrows behind teams of horses and had a personal reason for wanting tractors. This was rural Pennsylvania. The same families had lived here for generations and intermarried. My family were outlanders in this society, and in the first grade I was a "city slicker." Some of the older boys took me around the back of the school where two outhouses were located, one for girls and one for boys. I was invited to look through a knothole in the boys' two-holer and, when I did, a boy inside pissed in my face. I fought and was soundly whipped. When I got home, I got a whipping for my torn clothes. It did no good to complain of mistreatment by fellow students. The answer was "Fight back!" I quickly learned never to complain of mistreatment by a teacher. Parents and teachers had an inseparable union. Complain about a teacher and your parents would flay your backside. My eyesight was going. I could not read the writing on the blackboard from my seat. I was terrified. Any boy who wore glasses was looked down upon, teased, and tormented as "four eyes." I understood that once you got that nickname, you were branded. It lasted for life. I could not tell my parents that the world was becoming blurred.

I fought, was whipped, and fought again. I learned the hard way the importance of an attack philosophy. I also found if I took the blows, hung in there, and kept fighting, that I had more respect for myself. By the eighth grade I was King of the Hill. I kicked the ass of every boy in school that year and would not hesitate to give equal treatment to a mouthy girl.

Girls were strange. They could milk cows, churn butter, and even cut the lawn, but they could not fork hay or properly leap from the barn rafters into a straw mow. They were scared their dresses might lift, as though I cared. Not one in twenty of the girls owned cap pistols or a BB gun, yet they always wanted to play with us boys. They could never keep a secret no matter how dreadful the oath they swore. If we raided an apple orchard or put something on the railroad tracks, they would always tell. There was some rule that said girls had to stay clean. They had to sneak off to do everything, probably even to go to the toilet. Parents kept them under tight control. Older boys told me it had to do with something called "sex."

When I was a child, sex was never openly discussed by my parents. Once my mother and father had guests and the Virgin Islands were mentioned. Wanting to impress everyone, I piped up with "I know what a virgin is!" The adults were stricken dumb. Noticing that I had their undivided attention, I trumpeted, "Shirley . . . was a virgin until Harry . . . took her into the woods." I learned in a hurry to stay out of adult conversations.

This was subterfuge on the part of my parents. They knew about sex; they had to know about it. Any book my mother tried to keep from me had to contain "sex." One day I saw my mother reading a book called God's Little Acre. "Oh, this is so suggestive!" she would cry, but she could hardly wait to get to the next page.

A key element of education in a one-room country schoolhouse was corporal punishment. We were whipped for the slightest offense and sometimes were instructed to go into the woods beside the school and cut the switches we were beaten with. Any boy with self-respect carried a pocketknife, and lying that I did not have one was no help. There was always some girl who wanted to hear us yelp. I was caught reading Tom Sawyer during the period when another grade was reciting. The teacher made me hold out my hands and hit them again and again with a ruler. Most of us did not see a ruler as a measuring device. It was an instrument of torture.

It took a skilled liar to avoid punishment, and I practiced whenever possible. A boy gave me a condom and I felt like a big kid to own one. Unfortunately, I left it in the pocket of my overalls. My mom was doing the Monday washing and the Prudential Insurance man had stopped by to make collection, as was done in those days. While my mom talked, she ran her hand around the tubful of water and came up with a wet rubber draped across her finger. She was terribly embarrassed. As soon as the man left, she asked me if I was responsible. I lied that I was not. When my father came home, she gave him four types of hell while the poor man reeled in shock. It was not long before they both turned on me, and I babbled a terrified confession. My father handled the whipping with my mother cheering him on.

It remains my contention that a boy should be allowed some latitude as a liar in early years, otherwise he will be unable to deal with the opposite sex in later years.

My mother dreamed of going to Hawaii, but would never get there. Most people did not have the money to travel anywhere. We only went to visit relatives. Dad would pack us all in the car and we would drive to the area of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. This was a visit of adults and there was little for children to do. I have a memory of going out on a sidewalk to play. An elderly man came walking in my direction. His skin was very dark. When he came close to me, he left the sidewalk and walked in the street. The experience stayed with me. Adults did not act like that. I did not understand why an old man would give up a wide sidewalk to a child. Everyone in my country school had the same color skin that I did. Sometimes I would hear about a black family that lived near Mount Holly Springs, six miles away. People talked about them like a tourist attraction. "Oh yeah, we got some coloreds. There's them Gumbys live over at Mount Holly."

The Depression was a terrible experience for much of America. Fourteen million men were without jobs. They and their families lived in silent sadness and chewed poverty at mealtime. Anyone lucky enough to have a job worked hard to keep it. Entertainment was simple. In the 1930s and '40s, the family radio was our lifeline to the world. When I was very young, Saturday morning brought me the children's program Let's Pretend. Growing older, I eagerly looked forward to The Green Hornet, The Shadow, and I Love a Mystery. Radio allowed, indeed forced, listeners to use their imagination. I was terrified when Orson Welles did the program on the invasion of the Martians. We tuned in late and, like many others, thought it really was an invasion from outer space. I begged my father to shoot me before the Martians came. As I recall, he took a long look at me and seriously considered the idea.

There were simple country festivals with chicken corn soup, fiddlers, and cakewalks. Money was raised for the one-room country schoolhouse by holding box socials. Older girls coming on marriageable age would make a lunch for two, put it in a cardboard box, and wrap it with a pretty ribbon. The identity of the girl who made the box lunch was supposed to be a secret, but the girls usually told the boys they most liked the color of the paper or ribbon they used. The young men would then bid auction-style for the opportunity to sit and eat with the girl they liked.

A well-known song was "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" but thanks to my father's effort and foresight and my mother's thrift, we were doing well. We had a five-acre truck patch where we grew a wide variety of vegetables. We had hogs and chickens and steers for butchering. I learned how to capture a rooster, put his head on a stump, and chop it off with a hatchet. If they were then put on the ground, they would run around for a bit before they flopped over. The chicken was then put in hot water. It was a stinking job to pluck the feathers. Pigs were shot between the eyes with a .22-caliber rifle, their throats cut, and then they were hung up to be butchered. The saying was that we used everything but the squeal. There was nothing squeamish about farm life at this time. Farmers knew how to butcher an animal, and their women knew how to can fruit and vegetables. If you wanted to survive, you did what it took to do so.

From the Hardcover edition.

All things have a beginning; mine was the fifteenth of June 1929. As soon as the United States learned of the event, it went into that cataclysmic period of despair known as the Great Depression.

I was the descendant of a long line of citizen warriors. On my mother's side, they came from Holland in the 1600s and settled in the area of Bergen County, New Jersey. Later they moved to New York City and intermarried with the Scots and the Welsh. My father's line was German. Coming through Philadelphia in 1713, they meandered through the Cumberland Valley, down the Shenandoah, and settled in the Yadkin River area of North Carolina. In the Revolutionary War, my ancestors fought the British and paid the price of freedom. One died in an infamous British prison called the Sugar House. Another was murdered by Loyalists when he came home from the Battle of Guilford Court House. In the Civil War, my great-grandfathers fought each other, the one from the North serving from Bull Run to Antietam. He was an engineer and while under fire laid a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River during the Battle of Fredericksburg. The one from the South was an infantryman and fought at the Battles of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Captured in 1865, he ended his military career as a prisoner of war. An uncle sailed around the world with Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet, and my father served in the navy in World War I and survived an attack on his ship by a German submarine. His ship, the USS Pocahontas, was homeported in New York, where he met my mother.

My mother was named Emma; she was my rock and I adored her. Brooklyn-born and raised in poverty, she was an angel who could curse like a trooper. Until age eight, I thought my name was "Ya goddamn dope!" but it was always followed by hugs and kisses.

I never heard my father say anything stronger than "cripes," but he was a hard and dangerous man. He was a crack shot, who as a boy kept fresh-killed meat on the family table. North Carolina relatives told us that when my father was in the third grade, he was badly beaten by a teacher. He went home, got a .22-caliber rifle, stood outside ringing the school bell with bullets, and called on the teacher to come out. The teacher went out a side window, and my father did not go back to school. He was quick with his temper and his fists. In later years I asked my uncle what my grandfather had been like. "Oh, he was a hard man," he responded, "knock ya flat as quick as look at ya." Perhaps it was inherited, as that description fit my father.

A college degree was rare in the early twentieth century. Sober, hardworking, and determined, my father had come far on a third-grade education and correspondence courses. His name was Frank Black. As the chief engineer of C. H. Masland's rug mill in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he felt mathematics was the only study worth pursuing. After dinner, his standard direction was "Get your nose in a book," meaning a thick book of fractions and equations. Years later, after his death at age eighty-five, I found that book in our family library. On a page therein scrawled in a childish hand was the inscription "Fuck you, Frank Black!" I hated math and became determined to live my life without it. Fortunately, my mother taught me to love other books. I would sneak away to enjoy Dumas and Sir Walter Scott. I doted on the gunfire and flashing swords of Rafael Sabatini's Captain Blood and Scaramouche.

My father loved the outdoors. In 1932, when there were fourteen men lined up for every job and many farms were for sale, he used his grand salary of fifty dollars a week to buy a farm. It consisted of 146 acres, located between the two historic Pennsylvania towns of Carlisle and Gettysburg. We lived in a big stone house that dated from the early 1800s. We had a wooden house nearby for tenants and a large Pennsylvania bank barn, which had been built in 1854 by experienced carpenters. The frame was made of great logs held together by thick wooden pegs.

I grew up in a wonderful outdoor life of woods, streams, and mountains. My bond with my father was hunting together. I was shooting from the age of nine. I also had ample opportunity to visit the Gettysburg battlefield, where my parents and I were present in 1938 for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the battle. My father told me it would be the last gathering of Civil War veterans. It was hard to believe that those old men had ever been young. We watched as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) dedicated the peace light. The battlefield fascinated me, and I discussed it with those adults who would share time with a child.

We had a tenant house. One of the renters was a combat infantryman, a sergeant from World War I. He talked with me of battles and on occasion allowed me to wear the steel helmet he had brought home. I listened with rapt attention when my father or "Old Sarge" would talk of wartime experiences.

My brother and sister were older, so they went to the higher-grade schools in Carlisle. I was dispatched to a one-room country schoolhouse where eight grades were taught in the same small room by the same teacher. The Depression had its grip on the nation and poverty was rampant.

This was a time when workingmen were told "Don't need ya." There was no unemployment compensation, and the pink slip in the final paycheck was a fearful thing. The adults called it "the crash" and "hard times." For many people it was a time of endless struggle, an era when idealism faced reality and died. My father said people were not interested in ideals, they wanted a job. He was not for Roosevelt; he said FDR would oppose an idea until it passed and then claim it as his own. That sounded very slick to me.

My loving mother sent me off to my first day in school wearing a white silk shirt and an outfit called "Little Lord Fauntleroy." I found my companions were farm boys who went barefoot spring, summer, and fall. Some wore Farmer Brown bib overalls without shirts. Many girls wore dresses made from the covering cloth of feed and flour sacks. The cloth was produced in simple prints to entice farm families to buy the product.

When they saw me, the country boys could hardly believe their good fortune. Now they had something more in their lives than endless arguments over whether a John Deere farm tractor was better than an Allis Chalmers. To most of these boys, tractors represented the ultimate wealth. The older boys were already manhandling plows in furrows behind teams of horses and had a personal reason for wanting tractors. This was rural Pennsylvania. The same families had lived here for generations and intermarried. My family were outlanders in this society, and in the first grade I was a "city slicker." Some of the older boys took me around the back of the school where two outhouses were located, one for girls and one for boys. I was invited to look through a knothole in the boys' two-holer and, when I did, a boy inside pissed in my face. I fought and was soundly whipped. When I got home, I got a whipping for my torn clothes. It did no good to complain of mistreatment by fellow students. The answer was "Fight back!" I quickly learned never to complain of mistreatment by a teacher. Parents and teachers had an inseparable union. Complain about a teacher and your parents would flay your backside. My eyesight was going. I could not read the writing on the blackboard from my seat. I was terrified. Any boy who wore glasses was looked down upon, teased, and tormented as "four eyes." I understood that once you got that nickname, you were branded. It lasted for life. I could not tell my parents that the world was becoming blurred.

I fought, was whipped, and fought again. I learned the hard way the importance of an attack philosophy. I also found if I took the blows, hung in there, and kept fighting, that I had more respect for myself. By the eighth grade I was King of the Hill. I kicked the ass of every boy in school that year and would not hesitate to give equal treatment to a mouthy girl.

Girls were strange. They could milk cows, churn butter, and even cut the lawn, but they could not fork hay or properly leap from the barn rafters into a straw mow. They were scared their dresses might lift, as though I cared. Not one in twenty of the girls owned cap pistols or a BB gun, yet they always wanted to play with us boys. They could never keep a secret no matter how dreadful the oath they swore. If we raided an apple orchard or put something on the railroad tracks, they would always tell. There was some rule that said girls had to stay clean. They had to sneak off to do everything, probably even to go to the toilet. Parents kept them under tight control. Older boys told me it had to do with something called "sex."

When I was a child, sex was never openly discussed by my parents. Once my mother and father had guests and the Virgin Islands were mentioned. Wanting to impress everyone, I piped up with "I know what a virgin is!" The adults were stricken dumb. Noticing that I had their undivided attention, I trumpeted, "Shirley . . . was a virgin until Harry . . . took her into the woods." I learned in a hurry to stay out of adult conversations.

This was subterfuge on the part of my parents. They knew about sex; they had to know about it. Any book my mother tried to keep from me had to contain "sex." One day I saw my mother reading a book called God's Little Acre. "Oh, this is so suggestive!" she would cry, but she could hardly wait to get to the next page.

A key element of education in a one-room country schoolhouse was corporal punishment. We were whipped for the slightest offense and sometimes were instructed to go into the woods beside the school and cut the switches we were beaten with. Any boy with self-respect carried a pocketknife, and lying that I did not have one was no help. There was always some girl who wanted to hear us yelp. I was caught reading Tom Sawyer during the period when another grade was reciting. The teacher made me hold out my hands and hit them again and again with a ruler. Most of us did not see a ruler as a measuring device. It was an instrument of torture.

It took a skilled liar to avoid punishment, and I practiced whenever possible. A boy gave me a condom and I felt like a big kid to own one. Unfortunately, I left it in the pocket of my overalls. My mom was doing the Monday washing and the Prudential Insurance man had stopped by to make collection, as was done in those days. While my mom talked, she ran her hand around the tubful of water and came up with a wet rubber draped across her finger. She was terribly embarrassed. As soon as the man left, she asked me if I was responsible. I lied that I was not. When my father came home, she gave him four types of hell while the poor man reeled in shock. It was not long before they both turned on me, and I babbled a terrified confession. My father handled the whipping with my mother cheering him on.

It remains my contention that a boy should be allowed some latitude as a liar in early years, otherwise he will be unable to deal with the opposite sex in later years.

My mother dreamed of going to Hawaii, but would never get there. Most people did not have the money to travel anywhere. We only went to visit relatives. Dad would pack us all in the car and we would drive to the area of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. This was a visit of adults and there was little for children to do. I have a memory of going out on a sidewalk to play. An elderly man came walking in my direction. His skin was very dark. When he came close to me, he left the sidewalk and walked in the street. The experience stayed with me. Adults did not act like that. I did not understand why an old man would give up a wide sidewalk to a child. Everyone in my country school had the same color skin that I did. Sometimes I would hear about a black family that lived near Mount Holly Springs, six miles away. People talked about them like a tourist attraction. "Oh yeah, we got some coloreds. There's them Gumbys live over at Mount Holly."

The Depression was a terrible experience for much of America. Fourteen million men were without jobs. They and their families lived in silent sadness and chewed poverty at mealtime. Anyone lucky enough to have a job worked hard to keep it. Entertainment was simple. In the 1930s and '40s, the family radio was our lifeline to the world. When I was very young, Saturday morning brought me the children's program Let's Pretend. Growing older, I eagerly looked forward to The Green Hornet, The Shadow, and I Love a Mystery. Radio allowed, indeed forced, listeners to use their imagination. I was terrified when Orson Welles did the program on the invasion of the Martians. We tuned in late and, like many others, thought it really was an invasion from outer space. I begged my father to shoot me before the Martians came. As I recall, he took a long look at me and seriously considered the idea.

There were simple country festivals with chicken corn soup, fiddlers, and cakewalks. Money was raised for the one-room country schoolhouse by holding box socials. Older girls coming on marriageable age would make a lunch for two, put it in a cardboard box, and wrap it with a pretty ribbon. The identity of the girl who made the box lunch was supposed to be a secret, but the girls usually told the boys they most liked the color of the paper or ribbon they used. The young men would then bid auction-style for the opportunity to sit and eat with the girl they liked.

A well-known song was "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" but thanks to my father's effort and foresight and my mother's thrift, we were doing well. We had a five-acre truck patch where we grew a wide variety of vegetables. We had hogs and chickens and steers for butchering. I learned how to capture a rooster, put his head on a stump, and chop it off with a hatchet. If they were then put on the ground, they would run around for a bit before they flopped over. The chicken was then put in hot water. It was a stinking job to pluck the feathers. Pigs were shot between the eyes with a .22-caliber rifle, their throats cut, and then they were hung up to be butchered. The saying was that we used everything but the squeal. There was nothing squeamish about farm life at this time. Farmers knew how to butcher an animal, and their women knew how to can fruit and vegetables. If you wanted to survive, you did what it took to do so.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

An extraordinary testament to honor and heroism, this is the amazing true story of a highly decorated Korean and Vietnam veteran, military advisor, and renowned expert on America's elite Airborne Rangers.