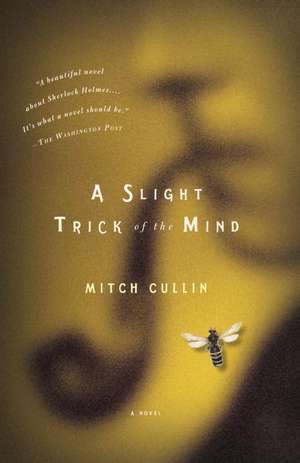

A Slight Trick of the Mind

Autor Mitch Cullinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Audies (2006)

Preț: 87.21 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 131

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.69€ • 17.47$ • 13.81£

16.69€ • 17.47$ • 13.81£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400078226

ISBN-10: 1400078229

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400078229

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Mitch Cullin is the author of six books, including the novel Tideland and the novel-in-verse Branches. He lives in California’s San Gabriel Valley, where in addition to writing fiction he collaborates on various projects with the artist Peter I. Chang.

Extras

Chapter 1

Upon arriving from his travels abroad, he entered his stone-built farmhouse on a summer’s afternoon, leaving the luggage by the front door for his housekeeper to manage. He then retreated into the library, where he sat quietly, glad to be surrounded by his books and the familiarity of home. For almost two months, he had been away, traveling by military train across India, by Royal Navy ship to Australia, and then finally setting foot on the occupied shores of postwar Japan. Going and returning, the same interminable routes had been taken–usually in the company of rowdy enlisted men, few of whom acknowledged the elderly gentleman dining or sitting beside them (that slow-walking geriatric, searching his pockets for a match he’d never find, chewing relentlessly on an unlit Jamaican cigar). Only on the rare occasions when an informed officer might announce his identity would the ruddy faces gaze with amazement, assessing him in that moment: For while he used two canes, his body remained unbowed, and the passing of years hadn’t dimmed his keen gray eyes; his snow-white hair, thick and long, like his beard, was combed straight back in the English fashion.

“Is that true? Are you really him?”

“I am afraid I still hold that distinction.”

“You are Sherlock Holmes? No, I don’t believe it.”

“That is quite all right. I scarcely believe it myself.”

But at last the journey was completed, though he found it difficult to summon the specifics of his days abroad. Instead, the whole vacation–while filling him like a satisfying meal–felt unfathomable in hindsight, punctuated here and there by brief remembrances that soon became vague impressions and were invariably forgotten again. Even so, he had the immutable rooms of his farmhouse, the rituals of his orderly country life, the reliability of his apiary–these things required no vast, let alone meager, amount of recall; they had simply become ingrained during his decades of isolation. Then there were the bees he tended: The world continued to change, as did he, but they persisted nonetheless. And after his eyes closed and his breaths resonated, it would be a bee that welcomed him home–a worker manifesting in his thoughts, finding him elsewhere, settling on his throat and stinging him.

Of course, when stung by a bee on the throat, he knew it was best to drink salt and water to prevent serious consequences. Naturally, the stinger should be pulled from the skin beforehand, preferably seconds after the poison’s instantaneous release. In his forty-four years of beekeeping on the southern slope of the Sussex Downs–living between Seaford and Eastbourne, the closest village being the tiny Cuckmere Haven–he had received exactly 7,816 stings from worker bees (almost always on the hands or face, occasionally on the earlobes or the neck or the throat: the cause and subsequent effects of every single prick dutifully contemplated, and later recorded into one of the many notebook journals he kept in his attic study). These mildly painful experiences, over time, had led him to a variety of remedies, each depending on which parts of his body had been stung and the ultimate depth to which the stinger had gone: salt with cold water, soft soap mixed with salt, then half of a raw onion applied to the irritation; when in extreme discomfort, wet mud or clay sometimes did the trick, as long as it was reapplied hourly, until the swelling was no longer apparent; however, to cure the smart, and also prevent inflammation, dampened tobacco rubbed immediately into the skin seemed the most effective solution.

Yet now–while sitting inside the library and napping in his armchair beside the empty fireplace–he was panicked within his dreaming, unable to recall what needed to be done for this sudden sting upon his Adam’s apple. He witnessed himself there, in his dream, standing upright among a stretching field of marigolds and clasping his neck with slender, arthritic fingers. Already the swelling had begun, bulging beneath his hands like a pronounced vein. A paralysis of fear overtook him, and he became stock-still as the swelling grew outward and inward (his fingers parted by the ballooning protuberance, his throat closing in on itself).

And there, too, in that field of marigolds, he saw himself contrasting amid the red and golden yellow beneath him. Naked, with his pale flesh exposed above the flowers, he resembled a brittle skeleton covered by a thin veneer of rice paper. Gone were the vestments of his retirement–the woolens, the tweeds, the reliable clothing he had worn daily since before the Great War, throughout the second Great War, and into his ninety-third year. His flowing hair had been shorn to the scalp, and his beard was reduced to a stubble on his jutting chin and sunken cheeks. The canes that aided his ambling–the very canes placed across his lap inside the library–had vanished as well within his dreaming. But he remained standing, even as his constricting throat blocked passage and his breathing became impossible. Only his lips moved, stammering noiselessly for air. Everything else–his body, the blossoming flowers, the clouds up high–offered no perceptible movement, all of it made static save those quivering lips and a solitary worker bee roaming its busy black legs about a creased forehead.

Chapter 2

Holmes gasped, waking. His eyelids lifted, and he glanced around the library while clearing his throat. Then he inhaled deeply, noting the slant of waning sunlight coming from a west-facing window: the resulting glow and shadow cast across the polished slats of the floor, creeping like clock hands, just enough to touch the hem of the Persian rug underneath his feet, told him it was precisely 5:18 in the afternoon.

“Have you stirred?” asked Mrs. Munro, his young housekeeper, who stood nearby, her back to him.

“Quite so,” he replied, his stare fixing on her slight form–the long hair pushed into a tight bun, the curling dark brown wisps hanging over her slender neck, the straps of her tan apron tied at her rear. From a wicker basket placed on the library table, she took out bundles of correspondence (letters bearing foreign postmarks, small packages, large envelopes), and, as instructed to do once a week, she began sorting them into appropriate stacks based on size.

“You was doing it in your nap, sir. That choking sound–you was doing it, same as before you went. Should I bring water?”

“I don’t believe it is required at present,” he said, absently clutching both canes.

“Suit yourself, then.”

She continued sorting–the letters to the left, the packages in the middle, the larger envelopes on the right. During his absence, the normally sparse table had filled with precarious stacks of communication. He knew there would certainly be gifts, odd items sent from afar. There would be requests for magazine or radio interviews, and there would be pleas for help (a lost pet, a stolen wedding ring, a missing child, an array of other hopeless trifles best left unanswered). Then there were the yet-to-be-published manuscripts: misleading and lurid fictions based on his past exploits, lofty explorations in criminology, galleys of mystery anthologies–along with flattering letters asking for an endorsement, a positive comment for a future dust jacket, or, possibly, an introduction to a text. Rarely did he respond to any of it, and never did he indulge journalists, writers, or publicity seekers.

Still, he usually perused every letter sent, examined the contents of every package delivered. That one day a week–regardless of a season’s warmth or chill–he worked at the table while the fireplace blazed, tearing open envelopes, scanning the subject matter before crumpling the paper and throwing it into the flames. The gifts, however, were put aside, set carefully into the wicker basket for Mrs. Munro to give to those who organized charitable works in the town. But if a missive addressed a specific interest, if it avoided servile praise and smartly addressed a mutual fascination with what concerned him most–the undertakings of producing a queen from a worker bee’s egg, the health benefits of royal jelly, perhaps a new insight regarding the cultivation of ethnic culinary herbs like prickly ash (nature’s far-flung oddities, which, as he believed royal jelly did, could stem the needless atrophy that often beset an elderly body and mind)–then the letter stood a fair chance of being spared incineration; it might find its way into his coat pocket instead, remaining there until he found himself at his attic study desk, his fingers finally retrieving the letter for further consideration. Sometimes these lucky letters beckoned him elsewhere: an herb garden beside a ruined abbey near Worthing, where a strange hybrid of burdock and red dock thrived; a bee farm outside of Dublin, bestowed by chance with a slightly acidic, though not unpalatable, batch of honey as a result of moisture covering the combs one particularly warm season; most recently, Shimonoseki, a Japanese town that offered specialty cuisine made from prickly ash, which, along with a diet of miso paste and fermented soybeans, seemed to afford the locals sustained longevity (the need for documentation and firsthand knowledge of such rare, possibly life-extending nourishment being the chief pursuit of his solitary years).

“You’ll live with this mess for an age,” said Mrs. Munro, nodding at the mail stacks. After lowering the empty wicker basket to the floor, she turned to him, saying, “There’s more, too, you know, out in the front hall closet–them boxes was cluttering up everything.”

“Very well, Mrs. Munro,” he said sharply, hoping to thwart any elaboration on her part.

“Should I bring the others in? Or should I wait for this bunch to be finished?”

“You can wait.”

He glanced at the doorway, indicating with his eyes that he wished for her withdrawal. But she ignored his stare, pausing instead to smooth her apron before continuing: “There’s an awful lot–in that hall closet, you know–I can’t tell you how much.”

“So I have gathered. I think for the moment I will focus on what is here.”

“I’d say you’ve got your hands full, sir. If you’re needing help–”

“I can take care of it–thank you.”

Intently this time, he gazed at the doorway, inclining his head in its direction.

“Are you hungry?” she asked, tentatively stepping onto the Persian rug and into the sunlight.

A scowl halted her approach, softening a bit as he sighed. “Not in the slightest” was his answer.

“Will you be eating this evening?”

“It is inevitable, I suppose.” He briefly envisioned her laboring recklessly in the kitchen, spilling offal on the countertops, or dropping bread crumbs and perfectly good slices of Stilton to the floor. “Are you intent on concocting your unsavory toad-in-the-hole?”

“You told me you didn’t like that,” she said, sounding surprised.

“I don’t, Mrs. Munro, I truly don’t–at least not your interpretation of it. Your shepherd’s pie, on the other hand, is a rare thing.”

Her expression brightened, even as she knitted her brow in contemplation. “Well, let’s see, I got leftover beef from the Sunday roast. I could use that–except I know how you prefer the lamb.”

“Leftover beef is acceptable.”

“Shepherd’s pie it is, then,” she said, her voice taking on a sudden urgency. “And so you’ll know, I’ve got your bags unpacked. Didn’t know what to do with that funny knife you brought, so it’s by your pillow. Mind you don’t cut yourself.” He sighed with greater effect, shutting his eyes completely, removing her from his sight altogether: “It is called a kusun-gobu, my dear, and I appreciate your concern–wouldn’t want to be stilettoed in my own bed.”

“Who would?”

His right hand fumbled into a coat pocket, his fingers feeling for the remainder of a half-consumed Jamaican. But, to his dismay, he had somehow misplaced the cigar (perhaps lost as he disembarked from the train earlier, as he stooped to retrieve a cane that had slipped from his grasp–possibly the Jamaican had escaped his pocket then, falling to the platform, only to get flattened underfoot). “Maybe,” he mumbled, “or maybe–”

He searched another pocket, listening while Mrs. Munro’s shoes went from the rug and crossed the slats and moved onward through the doorway (seven steps, enough to take her from the library). His fingers curled around a cylindrical tube (nearly the same length and circumference of the halved Jamaican, although by its weight and firmness, he readily discerned it wasn’t the cigar). And when lifting his eyelids, he beheld a clear glass vial sitting upright on his open palm; and peering closer, the sunlight glinting off the metal cap, he studied the two dead honeybees sealed within–one mingling upon the other, their legs intertwined, as if both had succumbed during an intimate embrace.

“Mrs. Munro–”

“Yes?” she replied, about-facing in the corridor and coming back with haste. “What is it?”

“Where is Roger?” he asked, returning the vial to his pocket.

She entered the library, covering the seven steps that had marked her departure. “Beg your pardon?”

“Your boy–Roger–where is he? I haven’t seen him about yet.”

“But, sir, he carried your bags inside for you, don’t you remember? Then you told him to go wait for you at them hives. You said you wanted him there for an inspection.”

A confused look spread across his pale, bearded face, and that puzzlement that occupied the moments when he sensed the failing of his own memory also threw its shadow over him (what else was forgotten, what else filtered away like sand seeping between clenched fists, and what exactly was known for sure anymore?), yet he attempted to push his worries aside by inducing a reasonable explanation for what confounded him from time to time.

“Of course, that is right. It was a tiring trip, you see. I haven’t slept much. Has he waited long?”

“A good while–didn’t take his tea–can’t imagine he minds a bit, though. Since you went, he’s cared more for them bees than his own mother, I can tell you.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, sadly it is.”

“Well, then,” he said, situating the canes, “I suppose I won’t keep the boy waiting any longer.”

Easing from the armchair, the canes bringing him to his feet, he proceeded for the doorway, wordlessly counting each step–one, two, three–while ignoring Mrs. Munro uttering behind him, “Want meat your side, sir? You got it all right, do you?” Four, five, six. He wouldn’t conceive of her frowning as he trudged forward, or foresee her spotting his Jamaican seconds after he exited the room (her bending before the armchair, pinching the foul-smelling cigar from the seat cushion, and depositing it in the fireplace). Seven, eight, nine, ten–eleven steps brought him into the corridor: four steps more than it took Mrs. Munro, and two steps more than his average.

Naturally, he concluded when catching his breath at the front door, a degree of sluggishness on his part wasn’t unexpected; he had ventured halfway around the world and back, forgoing his usual morning meal of royal jelly spread upon fried bread–the royal jelly, rich in vitamins of the B-complex and containing substantial amounts of sugars, proteins, and certain organic acids, was essential to maintaining his well-being and stamina; without its nourishment, he felt positive, his body had suffered somewhat, as had his retention.

But once outside, his mind was invigorated by the land awash in late-afternoon light. The flora posed no quandary, nor did the shadows hint at the voids where fragments of his memory should reside. Everything there was as it had been for decades–and so, too, was he: strolling effortlessly down the garden pathway, past the wild daffodils and the herb beds, past the deep purple buddleias and the giant thistles curling upward, inhaling all the while; a light breeze rustled the surrounding pines, and he savored the crunching sounds produced on the gravel from his shoes and canes. If he glanced back over his shoulder just now, he knew the farmhouse would be obscured behind four large pines–the front doorway and casements bedecked with climbing roses, the molded hoods above the windows, the exposed brick mullions of the outer walls; most of it barely visible among that dense crisscrossing of branches and pine needles. Ahead, where the path ended, stretched an undivided pasture enriched with a profusion of azaleas, laurel, and rhododendrons, beyond which loomed a cluster of freestanding oaks. And beneath the oaks–arranged on a straight-row plan, two hives to a group–existed his apiary.

Presently, he found himself pacing the beeyard as young Roger–eager to impress him with how well the bees had been tended in his absence, roving now from hive to hive without a veil and with sleeves rolled high–explained that after the swarm had been settled in early April, only a few days prior to Holmes’s leaving for Japan, they had since fully drawn out the foundation wax within the frames, built honeycombs, and filled each hexagonal cell. In fact, to his delight, the boy had already reduced the number of frames to nine per hive, thereby allowing plenty of space for the bees to thrive.

“Excellent,” Holmes said. “You have summered these creatures admirably, Roger. I am very pleased by your diligence here.” Then, rewarding the boy, he removed the vial from his pocket, presenting it between a crooked finger and a thumb. “This was meant for you,” he said, watching as Roger accepted the container and gazed at its contents with mild wonder. “Apis cerana japonica–or perhaps we will simply call them Japanese honeybees. How’s that?”

“Thank you, sir.”

The boy gave him a smile, and, gazing into Roger’s perfect blue eyes, lightly patting the boy’s mess of blond hair, Holmes smiled in turn. Afterward, they faced the hives together, saying nothing for a while. Silence like this, in the beeyard, never failed to please him wholly; from the way Roger stood easily beside him, he believed the boy shared an equal satisfaction. And while he rarely enjoyed the company of children, it was difficult avoiding the paternal stirrings he harbored for Mrs. Munro’s son (how, he had often pondered, could that meandering woman have borne such a promising offspring?).

But even at his advanced age, he found it impossible to express his true affections, especially toward a fourteen-year-old whose father had been among the British army casualties in the Balkans and whose presence, he suspected, Roger sorely missed. In any case, it was always wise to maintain emotional self-restraint when engaging housekeepers and their kin–it was, no doubt, enough just to stand with the boy as their mutual stillness hopefully spoke volumes, as their eyes surveyed the hives and studied the swaying oak branches and contemplated the subtle shifting of the afternoon into the evening.

Soon, Mrs. Munro called from the garden pathway, beckoning for Roger’s assistance in the kitchen. Then, reluctantly, he and the boy headed across the pasture, doing so at their leisure, stopping to observe a blue butterfly fluttering around the fragrant azaleas. Moments before dusk’s descent, they entered the garden, the boy’s hand gently gripping his elbow–that same hand guiding him onward through the farmhouse door, staying upon him until he had safely mounted the stairs and gone into his attic study (navigating the stairs being hardly a difficult undertaking, though he felt grateful whenever Roger steadied him like a human crutch).

“Should I fetch you when supper’s ready?”

“Please, if you would.”

“Yes, sir.”

So at his desk he sat, waiting for the boy to aid him again, to help him down the stairs. For a while, he busied himself, examining notes he had written prior to his trip, cryptic messages scrawled on torn bits of paper–levulose predominates, more soluble than dextrose–the meanings of which eluded him. He glanced around, realizing Mrs. Munro had taken liberties in his absence. The books he had scattered about the floor were now stacked, the floor swept, but–as he had expressly instructed–not a thing had been dusted. Becoming increasingly restless for tobacco, he shifted notebooks and opened drawers, hoping to find a Jamaican or at least a cigarette. After the hunt proved futile, he resigned himself with favored correspondence, reaching for one of the many letters sent by Mr. Tamiki Umezaki weeks before he had embarked on his trip abroad: Dear Sir, I’m extremely gratified that my invitation was received with serious interest, and that you have decided to be my guest here in Kobe. Needless to say, I look forward to showing you the many temple gardens in this region of Japan, as well as–

This, too, proved elusive: No sooner had he begun reading than his eyelids closed and his chin gradually sagged toward his chest. Then sleeping, he wouldn’t feel the letter slide through his fingers, or hear the faint choking emanating from his throat. And upon waking, he wouldn’t recall the field of marigolds where he had stood, nor would he remember the dream which had placed him there again. Instead, startled to find Roger suddenly leaning over him, he would clear his throat and stare at the boy’s vexed face and rasp with uncertainty, “Was I asleep?”

The boy nodded.

“I see–I see–”

“Your supper will be served soon.”

“Yes, my supper will be served soon,” he muttered, readying his canes.

As before, Roger gingerly assisted Holmes, helping him from the chair, sticking close to him when they exited the study; the boy traveled with him along the corridor, then down the stairs, then into the dining room, where, at last slipping past Roger’s light grasp, he went forward on his own, moving toward the large Victorian golden oak table and the single place setting that Mrs. Munro had laid for him.

“After I’m finished here,” Holmes said, addressing the boy without turning, “I would very much like to discuss the business of the apiary with you. I wish for you to relate all which has transpired there in my absence. I trust you can offer a detailed and accurate report.”

“I believe so,” the boy responded, watching from the doorway as Holmes propped his canes against the table before seating himself.

“Very well, then,” Holmes finally said, staring across the room to where Roger stood. “Let us reconvene at the library in an hour’s time, shall we? Providing, of course, that your mother’s shepherd’s pie doesn’t finish me off.”

“Yes, sir.”

Holmes reached for the folded napkin, shaking it open and tucking a corner underneath his collar. Sitting upright in the chair, he took a moment to align the flatware, arranging it neatly. Then he sighed through his nostrils, resting his hands evenly on either side of the empty plate: “Where is that woman?”

“I’m coming,” Mrs. Munro suddenly called. She promptly appeared behind Roger, holding a dinner tray that steamed with her cooking. “Move aside, son,” she told the boy. “You’re not helping nobody like that.”

“Sorry,” Roger said, shifting his slender body so that she could gain entrance. And once his mother had rushed by, hurrying to the table, he slowly took a step backward–and another, and another–until he had removed himself from the dining room. However, there would be no more loitering about on his part; otherwise, he knew, his mother might send him home or, at the very least, order him into the kitchen for cleanup duty. Avoiding that eventuality, he made his escape quietly enough, doing so while she served Holmes, stealing away before she could leave the dining room and summon him by name.

But the boy didn’t head outside, fleeing toward the beeyard like his mother might expect–nor did he go inside the library and prepare for Holmes’s questions concerning the apiary. Instead, he crept back upstairs, entering that one room in which only Holmes was allowed to sequester himself: the attic study. In truth, during the weeks that Holmes was traveling abroad, Roger had spent long hours exploring the study–initially taking various old books, dusty monographs, and scientific journals off the shelves, perusing them as he sat at the desk. When his curiosity had been satisfied, he had carefully placed them again on the shelves, making sure they looked untouched. On occasion, he had even pretended that he was Holmes, reclining in the desk chair with his fingertips pressed together, gazing at the window, and inhaling imaginary smoke.

Naturally, his mother was oblivious to his trespassing, for if she had found out, he would have been banished from the house altogether. Yet the more he explored the study (tentatively at first, his hands kept in his pockets), the more daring he became–peeking inside drawers, shaking letters from already-opened envelopes, respectfully holding the pen and scissors and magnifying glass that Holmes had used on a regular basis. Later on, he had begun sifting through the stacks of handwritten pages upon the desktop, mindful not to leave any identifying marks on the pages while, at the same time, trying to decipher Holmes’s notes and incomplete paragraphs; except most of what was read was lost on the boy–either due to the nature of Holmes’s often nonsensical scribbling or as a result of the subject matter being somewhat oblique and clinical. Still, he had studied every page, wishing to learn something unique or revealing about the famous man who now reigned over the apiary.

Roger would, in fact, discover little that shed new light on Holmes. The man’s world, it seemed, was one of hard evidence and uncontestable facts, detailed observations on external matters, with rarely a sentence of contemplation pertaining to himself. Yet among the many piles of random notes and writings, buried beneath it all as if hidden, the boy had eventually come across an item of true interest–a short unfinished manuscript entitled “The Glass Armonicist,” the sheaf of pages kept together by a rubber band. As opposed to Holmes’s other writings on the desk, this manuscript, the boy had immediately noticed, had been composed with great care: The words were easy to distinguish, nothing had been scratched out, and nothing was crammed into the margins or obscured by droplets of ink. What he then read had held his attention–for it was accessible and somewhat personal in nature, recounting an earlier time in Holmes’s life. But much to Roger’s chagrin, the manuscript ended abruptly after only two chapters, leaving its conclusion a mystery. Even so, the boy would dig it out again and again, rereading the text with a hope that he might gather some insight that had previously been missed.

And now, just as during those weeks when Holmes had been gone, Roger sat nervously at the study desk, methodically extracting the manuscript from underneath the organized disorder. Soon the rubber band was set aside, the pages placed near the glow of the table lamp. He studied the manuscript in reverse, briefly scanning the last few pages, while also feeling certain that Holmes had not yet had a chance to continue the text. Then he started at the beginning, bending forward as he read, turning one page over onto another page. If he concentrated without distractions, Roger believed, he could probably get through the first chapter that night. Only when his mother called his name would his head momentarily lift; she was outside, shouting for him from the garden below, searching for him. After her voice faded, he lowered his head once more, reminding himself that he didn’t have much time left–in less than an hour, he was expected at the library; before long the manuscript would need to be concealed exactly as it had originally been found. Until then, an index finger slid below Holmes’s words, blue eyes blinked repeatedly but remained focused, and lips moved without sound as sentences began conjuring familiar scenes within the boy’s mind.

From the Hardcover edition.

Upon arriving from his travels abroad, he entered his stone-built farmhouse on a summer’s afternoon, leaving the luggage by the front door for his housekeeper to manage. He then retreated into the library, where he sat quietly, glad to be surrounded by his books and the familiarity of home. For almost two months, he had been away, traveling by military train across India, by Royal Navy ship to Australia, and then finally setting foot on the occupied shores of postwar Japan. Going and returning, the same interminable routes had been taken–usually in the company of rowdy enlisted men, few of whom acknowledged the elderly gentleman dining or sitting beside them (that slow-walking geriatric, searching his pockets for a match he’d never find, chewing relentlessly on an unlit Jamaican cigar). Only on the rare occasions when an informed officer might announce his identity would the ruddy faces gaze with amazement, assessing him in that moment: For while he used two canes, his body remained unbowed, and the passing of years hadn’t dimmed his keen gray eyes; his snow-white hair, thick and long, like his beard, was combed straight back in the English fashion.

“Is that true? Are you really him?”

“I am afraid I still hold that distinction.”

“You are Sherlock Holmes? No, I don’t believe it.”

“That is quite all right. I scarcely believe it myself.”

But at last the journey was completed, though he found it difficult to summon the specifics of his days abroad. Instead, the whole vacation–while filling him like a satisfying meal–felt unfathomable in hindsight, punctuated here and there by brief remembrances that soon became vague impressions and were invariably forgotten again. Even so, he had the immutable rooms of his farmhouse, the rituals of his orderly country life, the reliability of his apiary–these things required no vast, let alone meager, amount of recall; they had simply become ingrained during his decades of isolation. Then there were the bees he tended: The world continued to change, as did he, but they persisted nonetheless. And after his eyes closed and his breaths resonated, it would be a bee that welcomed him home–a worker manifesting in his thoughts, finding him elsewhere, settling on his throat and stinging him.

Of course, when stung by a bee on the throat, he knew it was best to drink salt and water to prevent serious consequences. Naturally, the stinger should be pulled from the skin beforehand, preferably seconds after the poison’s instantaneous release. In his forty-four years of beekeeping on the southern slope of the Sussex Downs–living between Seaford and Eastbourne, the closest village being the tiny Cuckmere Haven–he had received exactly 7,816 stings from worker bees (almost always on the hands or face, occasionally on the earlobes or the neck or the throat: the cause and subsequent effects of every single prick dutifully contemplated, and later recorded into one of the many notebook journals he kept in his attic study). These mildly painful experiences, over time, had led him to a variety of remedies, each depending on which parts of his body had been stung and the ultimate depth to which the stinger had gone: salt with cold water, soft soap mixed with salt, then half of a raw onion applied to the irritation; when in extreme discomfort, wet mud or clay sometimes did the trick, as long as it was reapplied hourly, until the swelling was no longer apparent; however, to cure the smart, and also prevent inflammation, dampened tobacco rubbed immediately into the skin seemed the most effective solution.

Yet now–while sitting inside the library and napping in his armchair beside the empty fireplace–he was panicked within his dreaming, unable to recall what needed to be done for this sudden sting upon his Adam’s apple. He witnessed himself there, in his dream, standing upright among a stretching field of marigolds and clasping his neck with slender, arthritic fingers. Already the swelling had begun, bulging beneath his hands like a pronounced vein. A paralysis of fear overtook him, and he became stock-still as the swelling grew outward and inward (his fingers parted by the ballooning protuberance, his throat closing in on itself).

And there, too, in that field of marigolds, he saw himself contrasting amid the red and golden yellow beneath him. Naked, with his pale flesh exposed above the flowers, he resembled a brittle skeleton covered by a thin veneer of rice paper. Gone were the vestments of his retirement–the woolens, the tweeds, the reliable clothing he had worn daily since before the Great War, throughout the second Great War, and into his ninety-third year. His flowing hair had been shorn to the scalp, and his beard was reduced to a stubble on his jutting chin and sunken cheeks. The canes that aided his ambling–the very canes placed across his lap inside the library–had vanished as well within his dreaming. But he remained standing, even as his constricting throat blocked passage and his breathing became impossible. Only his lips moved, stammering noiselessly for air. Everything else–his body, the blossoming flowers, the clouds up high–offered no perceptible movement, all of it made static save those quivering lips and a solitary worker bee roaming its busy black legs about a creased forehead.

Chapter 2

Holmes gasped, waking. His eyelids lifted, and he glanced around the library while clearing his throat. Then he inhaled deeply, noting the slant of waning sunlight coming from a west-facing window: the resulting glow and shadow cast across the polished slats of the floor, creeping like clock hands, just enough to touch the hem of the Persian rug underneath his feet, told him it was precisely 5:18 in the afternoon.

“Have you stirred?” asked Mrs. Munro, his young housekeeper, who stood nearby, her back to him.

“Quite so,” he replied, his stare fixing on her slight form–the long hair pushed into a tight bun, the curling dark brown wisps hanging over her slender neck, the straps of her tan apron tied at her rear. From a wicker basket placed on the library table, she took out bundles of correspondence (letters bearing foreign postmarks, small packages, large envelopes), and, as instructed to do once a week, she began sorting them into appropriate stacks based on size.

“You was doing it in your nap, sir. That choking sound–you was doing it, same as before you went. Should I bring water?”

“I don’t believe it is required at present,” he said, absently clutching both canes.

“Suit yourself, then.”

She continued sorting–the letters to the left, the packages in the middle, the larger envelopes on the right. During his absence, the normally sparse table had filled with precarious stacks of communication. He knew there would certainly be gifts, odd items sent from afar. There would be requests for magazine or radio interviews, and there would be pleas for help (a lost pet, a stolen wedding ring, a missing child, an array of other hopeless trifles best left unanswered). Then there were the yet-to-be-published manuscripts: misleading and lurid fictions based on his past exploits, lofty explorations in criminology, galleys of mystery anthologies–along with flattering letters asking for an endorsement, a positive comment for a future dust jacket, or, possibly, an introduction to a text. Rarely did he respond to any of it, and never did he indulge journalists, writers, or publicity seekers.

Still, he usually perused every letter sent, examined the contents of every package delivered. That one day a week–regardless of a season’s warmth or chill–he worked at the table while the fireplace blazed, tearing open envelopes, scanning the subject matter before crumpling the paper and throwing it into the flames. The gifts, however, were put aside, set carefully into the wicker basket for Mrs. Munro to give to those who organized charitable works in the town. But if a missive addressed a specific interest, if it avoided servile praise and smartly addressed a mutual fascination with what concerned him most–the undertakings of producing a queen from a worker bee’s egg, the health benefits of royal jelly, perhaps a new insight regarding the cultivation of ethnic culinary herbs like prickly ash (nature’s far-flung oddities, which, as he believed royal jelly did, could stem the needless atrophy that often beset an elderly body and mind)–then the letter stood a fair chance of being spared incineration; it might find its way into his coat pocket instead, remaining there until he found himself at his attic study desk, his fingers finally retrieving the letter for further consideration. Sometimes these lucky letters beckoned him elsewhere: an herb garden beside a ruined abbey near Worthing, where a strange hybrid of burdock and red dock thrived; a bee farm outside of Dublin, bestowed by chance with a slightly acidic, though not unpalatable, batch of honey as a result of moisture covering the combs one particularly warm season; most recently, Shimonoseki, a Japanese town that offered specialty cuisine made from prickly ash, which, along with a diet of miso paste and fermented soybeans, seemed to afford the locals sustained longevity (the need for documentation and firsthand knowledge of such rare, possibly life-extending nourishment being the chief pursuit of his solitary years).

“You’ll live with this mess for an age,” said Mrs. Munro, nodding at the mail stacks. After lowering the empty wicker basket to the floor, she turned to him, saying, “There’s more, too, you know, out in the front hall closet–them boxes was cluttering up everything.”

“Very well, Mrs. Munro,” he said sharply, hoping to thwart any elaboration on her part.

“Should I bring the others in? Or should I wait for this bunch to be finished?”

“You can wait.”

He glanced at the doorway, indicating with his eyes that he wished for her withdrawal. But she ignored his stare, pausing instead to smooth her apron before continuing: “There’s an awful lot–in that hall closet, you know–I can’t tell you how much.”

“So I have gathered. I think for the moment I will focus on what is here.”

“I’d say you’ve got your hands full, sir. If you’re needing help–”

“I can take care of it–thank you.”

Intently this time, he gazed at the doorway, inclining his head in its direction.

“Are you hungry?” she asked, tentatively stepping onto the Persian rug and into the sunlight.

A scowl halted her approach, softening a bit as he sighed. “Not in the slightest” was his answer.

“Will you be eating this evening?”

“It is inevitable, I suppose.” He briefly envisioned her laboring recklessly in the kitchen, spilling offal on the countertops, or dropping bread crumbs and perfectly good slices of Stilton to the floor. “Are you intent on concocting your unsavory toad-in-the-hole?”

“You told me you didn’t like that,” she said, sounding surprised.

“I don’t, Mrs. Munro, I truly don’t–at least not your interpretation of it. Your shepherd’s pie, on the other hand, is a rare thing.”

Her expression brightened, even as she knitted her brow in contemplation. “Well, let’s see, I got leftover beef from the Sunday roast. I could use that–except I know how you prefer the lamb.”

“Leftover beef is acceptable.”

“Shepherd’s pie it is, then,” she said, her voice taking on a sudden urgency. “And so you’ll know, I’ve got your bags unpacked. Didn’t know what to do with that funny knife you brought, so it’s by your pillow. Mind you don’t cut yourself.” He sighed with greater effect, shutting his eyes completely, removing her from his sight altogether: “It is called a kusun-gobu, my dear, and I appreciate your concern–wouldn’t want to be stilettoed in my own bed.”

“Who would?”

His right hand fumbled into a coat pocket, his fingers feeling for the remainder of a half-consumed Jamaican. But, to his dismay, he had somehow misplaced the cigar (perhaps lost as he disembarked from the train earlier, as he stooped to retrieve a cane that had slipped from his grasp–possibly the Jamaican had escaped his pocket then, falling to the platform, only to get flattened underfoot). “Maybe,” he mumbled, “or maybe–”

He searched another pocket, listening while Mrs. Munro’s shoes went from the rug and crossed the slats and moved onward through the doorway (seven steps, enough to take her from the library). His fingers curled around a cylindrical tube (nearly the same length and circumference of the halved Jamaican, although by its weight and firmness, he readily discerned it wasn’t the cigar). And when lifting his eyelids, he beheld a clear glass vial sitting upright on his open palm; and peering closer, the sunlight glinting off the metal cap, he studied the two dead honeybees sealed within–one mingling upon the other, their legs intertwined, as if both had succumbed during an intimate embrace.

“Mrs. Munro–”

“Yes?” she replied, about-facing in the corridor and coming back with haste. “What is it?”

“Where is Roger?” he asked, returning the vial to his pocket.

She entered the library, covering the seven steps that had marked her departure. “Beg your pardon?”

“Your boy–Roger–where is he? I haven’t seen him about yet.”

“But, sir, he carried your bags inside for you, don’t you remember? Then you told him to go wait for you at them hives. You said you wanted him there for an inspection.”

A confused look spread across his pale, bearded face, and that puzzlement that occupied the moments when he sensed the failing of his own memory also threw its shadow over him (what else was forgotten, what else filtered away like sand seeping between clenched fists, and what exactly was known for sure anymore?), yet he attempted to push his worries aside by inducing a reasonable explanation for what confounded him from time to time.

“Of course, that is right. It was a tiring trip, you see. I haven’t slept much. Has he waited long?”

“A good while–didn’t take his tea–can’t imagine he minds a bit, though. Since you went, he’s cared more for them bees than his own mother, I can tell you.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, sadly it is.”

“Well, then,” he said, situating the canes, “I suppose I won’t keep the boy waiting any longer.”

Easing from the armchair, the canes bringing him to his feet, he proceeded for the doorway, wordlessly counting each step–one, two, three–while ignoring Mrs. Munro uttering behind him, “Want meat your side, sir? You got it all right, do you?” Four, five, six. He wouldn’t conceive of her frowning as he trudged forward, or foresee her spotting his Jamaican seconds after he exited the room (her bending before the armchair, pinching the foul-smelling cigar from the seat cushion, and depositing it in the fireplace). Seven, eight, nine, ten–eleven steps brought him into the corridor: four steps more than it took Mrs. Munro, and two steps more than his average.

Naturally, he concluded when catching his breath at the front door, a degree of sluggishness on his part wasn’t unexpected; he had ventured halfway around the world and back, forgoing his usual morning meal of royal jelly spread upon fried bread–the royal jelly, rich in vitamins of the B-complex and containing substantial amounts of sugars, proteins, and certain organic acids, was essential to maintaining his well-being and stamina; without its nourishment, he felt positive, his body had suffered somewhat, as had his retention.

But once outside, his mind was invigorated by the land awash in late-afternoon light. The flora posed no quandary, nor did the shadows hint at the voids where fragments of his memory should reside. Everything there was as it had been for decades–and so, too, was he: strolling effortlessly down the garden pathway, past the wild daffodils and the herb beds, past the deep purple buddleias and the giant thistles curling upward, inhaling all the while; a light breeze rustled the surrounding pines, and he savored the crunching sounds produced on the gravel from his shoes and canes. If he glanced back over his shoulder just now, he knew the farmhouse would be obscured behind four large pines–the front doorway and casements bedecked with climbing roses, the molded hoods above the windows, the exposed brick mullions of the outer walls; most of it barely visible among that dense crisscrossing of branches and pine needles. Ahead, where the path ended, stretched an undivided pasture enriched with a profusion of azaleas, laurel, and rhododendrons, beyond which loomed a cluster of freestanding oaks. And beneath the oaks–arranged on a straight-row plan, two hives to a group–existed his apiary.

Presently, he found himself pacing the beeyard as young Roger–eager to impress him with how well the bees had been tended in his absence, roving now from hive to hive without a veil and with sleeves rolled high–explained that after the swarm had been settled in early April, only a few days prior to Holmes’s leaving for Japan, they had since fully drawn out the foundation wax within the frames, built honeycombs, and filled each hexagonal cell. In fact, to his delight, the boy had already reduced the number of frames to nine per hive, thereby allowing plenty of space for the bees to thrive.

“Excellent,” Holmes said. “You have summered these creatures admirably, Roger. I am very pleased by your diligence here.” Then, rewarding the boy, he removed the vial from his pocket, presenting it between a crooked finger and a thumb. “This was meant for you,” he said, watching as Roger accepted the container and gazed at its contents with mild wonder. “Apis cerana japonica–or perhaps we will simply call them Japanese honeybees. How’s that?”

“Thank you, sir.”

The boy gave him a smile, and, gazing into Roger’s perfect blue eyes, lightly patting the boy’s mess of blond hair, Holmes smiled in turn. Afterward, they faced the hives together, saying nothing for a while. Silence like this, in the beeyard, never failed to please him wholly; from the way Roger stood easily beside him, he believed the boy shared an equal satisfaction. And while he rarely enjoyed the company of children, it was difficult avoiding the paternal stirrings he harbored for Mrs. Munro’s son (how, he had often pondered, could that meandering woman have borne such a promising offspring?).

But even at his advanced age, he found it impossible to express his true affections, especially toward a fourteen-year-old whose father had been among the British army casualties in the Balkans and whose presence, he suspected, Roger sorely missed. In any case, it was always wise to maintain emotional self-restraint when engaging housekeepers and their kin–it was, no doubt, enough just to stand with the boy as their mutual stillness hopefully spoke volumes, as their eyes surveyed the hives and studied the swaying oak branches and contemplated the subtle shifting of the afternoon into the evening.

Soon, Mrs. Munro called from the garden pathway, beckoning for Roger’s assistance in the kitchen. Then, reluctantly, he and the boy headed across the pasture, doing so at their leisure, stopping to observe a blue butterfly fluttering around the fragrant azaleas. Moments before dusk’s descent, they entered the garden, the boy’s hand gently gripping his elbow–that same hand guiding him onward through the farmhouse door, staying upon him until he had safely mounted the stairs and gone into his attic study (navigating the stairs being hardly a difficult undertaking, though he felt grateful whenever Roger steadied him like a human crutch).

“Should I fetch you when supper’s ready?”

“Please, if you would.”

“Yes, sir.”

So at his desk he sat, waiting for the boy to aid him again, to help him down the stairs. For a while, he busied himself, examining notes he had written prior to his trip, cryptic messages scrawled on torn bits of paper–levulose predominates, more soluble than dextrose–the meanings of which eluded him. He glanced around, realizing Mrs. Munro had taken liberties in his absence. The books he had scattered about the floor were now stacked, the floor swept, but–as he had expressly instructed–not a thing had been dusted. Becoming increasingly restless for tobacco, he shifted notebooks and opened drawers, hoping to find a Jamaican or at least a cigarette. After the hunt proved futile, he resigned himself with favored correspondence, reaching for one of the many letters sent by Mr. Tamiki Umezaki weeks before he had embarked on his trip abroad: Dear Sir, I’m extremely gratified that my invitation was received with serious interest, and that you have decided to be my guest here in Kobe. Needless to say, I look forward to showing you the many temple gardens in this region of Japan, as well as–

This, too, proved elusive: No sooner had he begun reading than his eyelids closed and his chin gradually sagged toward his chest. Then sleeping, he wouldn’t feel the letter slide through his fingers, or hear the faint choking emanating from his throat. And upon waking, he wouldn’t recall the field of marigolds where he had stood, nor would he remember the dream which had placed him there again. Instead, startled to find Roger suddenly leaning over him, he would clear his throat and stare at the boy’s vexed face and rasp with uncertainty, “Was I asleep?”

The boy nodded.

“I see–I see–”

“Your supper will be served soon.”

“Yes, my supper will be served soon,” he muttered, readying his canes.

As before, Roger gingerly assisted Holmes, helping him from the chair, sticking close to him when they exited the study; the boy traveled with him along the corridor, then down the stairs, then into the dining room, where, at last slipping past Roger’s light grasp, he went forward on his own, moving toward the large Victorian golden oak table and the single place setting that Mrs. Munro had laid for him.

“After I’m finished here,” Holmes said, addressing the boy without turning, “I would very much like to discuss the business of the apiary with you. I wish for you to relate all which has transpired there in my absence. I trust you can offer a detailed and accurate report.”

“I believe so,” the boy responded, watching from the doorway as Holmes propped his canes against the table before seating himself.

“Very well, then,” Holmes finally said, staring across the room to where Roger stood. “Let us reconvene at the library in an hour’s time, shall we? Providing, of course, that your mother’s shepherd’s pie doesn’t finish me off.”

“Yes, sir.”

Holmes reached for the folded napkin, shaking it open and tucking a corner underneath his collar. Sitting upright in the chair, he took a moment to align the flatware, arranging it neatly. Then he sighed through his nostrils, resting his hands evenly on either side of the empty plate: “Where is that woman?”

“I’m coming,” Mrs. Munro suddenly called. She promptly appeared behind Roger, holding a dinner tray that steamed with her cooking. “Move aside, son,” she told the boy. “You’re not helping nobody like that.”

“Sorry,” Roger said, shifting his slender body so that she could gain entrance. And once his mother had rushed by, hurrying to the table, he slowly took a step backward–and another, and another–until he had removed himself from the dining room. However, there would be no more loitering about on his part; otherwise, he knew, his mother might send him home or, at the very least, order him into the kitchen for cleanup duty. Avoiding that eventuality, he made his escape quietly enough, doing so while she served Holmes, stealing away before she could leave the dining room and summon him by name.

But the boy didn’t head outside, fleeing toward the beeyard like his mother might expect–nor did he go inside the library and prepare for Holmes’s questions concerning the apiary. Instead, he crept back upstairs, entering that one room in which only Holmes was allowed to sequester himself: the attic study. In truth, during the weeks that Holmes was traveling abroad, Roger had spent long hours exploring the study–initially taking various old books, dusty monographs, and scientific journals off the shelves, perusing them as he sat at the desk. When his curiosity had been satisfied, he had carefully placed them again on the shelves, making sure they looked untouched. On occasion, he had even pretended that he was Holmes, reclining in the desk chair with his fingertips pressed together, gazing at the window, and inhaling imaginary smoke.

Naturally, his mother was oblivious to his trespassing, for if she had found out, he would have been banished from the house altogether. Yet the more he explored the study (tentatively at first, his hands kept in his pockets), the more daring he became–peeking inside drawers, shaking letters from already-opened envelopes, respectfully holding the pen and scissors and magnifying glass that Holmes had used on a regular basis. Later on, he had begun sifting through the stacks of handwritten pages upon the desktop, mindful not to leave any identifying marks on the pages while, at the same time, trying to decipher Holmes’s notes and incomplete paragraphs; except most of what was read was lost on the boy–either due to the nature of Holmes’s often nonsensical scribbling or as a result of the subject matter being somewhat oblique and clinical. Still, he had studied every page, wishing to learn something unique or revealing about the famous man who now reigned over the apiary.

Roger would, in fact, discover little that shed new light on Holmes. The man’s world, it seemed, was one of hard evidence and uncontestable facts, detailed observations on external matters, with rarely a sentence of contemplation pertaining to himself. Yet among the many piles of random notes and writings, buried beneath it all as if hidden, the boy had eventually come across an item of true interest–a short unfinished manuscript entitled “The Glass Armonicist,” the sheaf of pages kept together by a rubber band. As opposed to Holmes’s other writings on the desk, this manuscript, the boy had immediately noticed, had been composed with great care: The words were easy to distinguish, nothing had been scratched out, and nothing was crammed into the margins or obscured by droplets of ink. What he then read had held his attention–for it was accessible and somewhat personal in nature, recounting an earlier time in Holmes’s life. But much to Roger’s chagrin, the manuscript ended abruptly after only two chapters, leaving its conclusion a mystery. Even so, the boy would dig it out again and again, rereading the text with a hope that he might gather some insight that had previously been missed.

And now, just as during those weeks when Holmes had been gone, Roger sat nervously at the study desk, methodically extracting the manuscript from underneath the organized disorder. Soon the rubber band was set aside, the pages placed near the glow of the table lamp. He studied the manuscript in reverse, briefly scanning the last few pages, while also feeling certain that Holmes had not yet had a chance to continue the text. Then he started at the beginning, bending forward as he read, turning one page over onto another page. If he concentrated without distractions, Roger believed, he could probably get through the first chapter that night. Only when his mother called his name would his head momentarily lift; she was outside, shouting for him from the garden below, searching for him. After her voice faded, he lowered his head once more, reminding himself that he didn’t have much time left–in less than an hour, he was expected at the library; before long the manuscript would need to be concealed exactly as it had originally been found. Until then, an index finger slid below Holmes’s words, blue eyes blinked repeatedly but remained focused, and lips moved without sound as sentences began conjuring familiar scenes within the boy’s mind.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A beautiful novel about Sherlock Holmes. . . . It’s what a novel should be.” —The Washington Post

“Wonderfully written and heartbreaking.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A wise and touching examination of the human condition.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Quite extraordinary. . . . Our hero–our eternal hero–has never been more heroic, or more human.” —The Village Voice

“Beautiful. . . . Cullin is an unusually sophisticated theorist of human nature.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Wonderfully written and heartbreaking.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A wise and touching examination of the human condition.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Quite extraordinary. . . . Our hero–our eternal hero–has never been more heroic, or more human.” —The Village Voice

“Beautiful. . . . Cullin is an unusually sophisticated theorist of human nature.” —The New York Times Book Review

Descriere

Cullin goes behind Sherlock Holmes's cool, unflappable surface to reveal for the first time the inner world of an obsessively private man. The author weaves together Holmes's hidden past and private struggles to transform him into an ordinary man, confronting and acquiescing to emotions he's resisted his entire life.

Premii

- Audies Winner, 2006