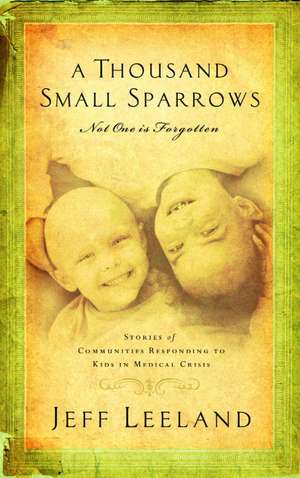

A Thousand Small Sparrows: Amazing Stories of Kids Helping Kids

Autor Jeff Leeland Marcus Brothertonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2007

Sometimes it’s the small who are mighty and the young who are wise.…

Kids will do heroic things when they have heroic things to do. Out of the Leelands’ experience came Sparrow Clubs USA, an organization of kids helping kids in medical need. Each child helped by Sparrow Clubs faces a battle for life, and yet each of these sparrows lives with a vibrant courage.

Taking you into the communities that became sanctuaries of love for families in need, A Thousand Small Sparrows will revive your hope in the Father heart of a God who cares. This is a book about the power of compassion that can change the world–one sparrow at a time.

One hundred percent of the author’s proceeds from this book will benefit Sparrow Clubs USA

Preț: 111.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.37€ • 22.38$ • 17.69£

21.37€ • 22.38$ • 17.69£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 01-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781590529331

ISBN-10: 1590529332

Pagini: 238

Dimensiuni: 139 x 212 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Multnomah Books

ISBN-10: 1590529332

Pagini: 238

Dimensiuni: 139 x 212 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Multnomah Books

Notă biografică

Jeff Leeland is a popular speaker and founder of the national youth-based charity Sparrow Clubs USA. His first book, One Small Sparrow, won the 1996 Christopher Award for “literary works that affirm the highest values of the human spirit.” Jeff and his wife and their five children live in Redmond, Oregon. Marcus Brotherton is a newspaper editor and freelance writer in Vancouver, Washington, and he holds a master’s degree in practical theology from Talbot Seminary.

Extras

Jacob the Boxer

Jacob’s face looked like it had gone twelve rounds. Bruised, battered, black-and-blue–this was no way for a newborn to spend his first few moments in the world.

“Nine pounds, eight ounces,” the scales read. The nurse repeated the information. Lying on the birthing bed, Priscilla Jove could hardly believe it. Her new son was huge–and he was three weeks early. But what did it matter? Aside from the severe bruising, Jacob checked out completely healthy. Her new son was perfect.

Priscilla had worried that maybe this pregnancy wouldn’t be as smooth as her first two. Labor had been quick this time–only fortyfive minutes. The drugs she had been given made pushing sudden and harsh. Jacob fought his way out like a boxer. He arrived glorious, wet, and triumphant, although a bit beat up. He would be tough, just like his dad, Sean Jove.

That Priscilla and Sean were having children at all was a miracle. Years earlier, when the couple lived in Los Angeles, they had been dubbed infertile. They had run the gamut of treatments. Hormone shots just made Priscilla crazy. She took them anyway, but in the end– after hot flashes, waiting, praying, hoping, money out the door–still nothing. One day, in desperation, she fell on her hands and knees before God and turned it all over to Him.

“Lord,” she said, “it has to be from You.”

Two months later she was pregnant.

Priscilla got prepared. If pregnancy, birth, and child rearing were about being organized, she wanted to get an A-plus. She scoured bookstores, devouring everything she could find. She made lists. She planned. She sorted. The couple’s first child, Sarah, was born right on schedule. Two years later, the details worked out perfectly again. Another daughter, Libby, arrived like clockwork.

The girls were bright, brilliant, beautiful. Priscilla and Sean were thrilled. Still, it felt like a member of the family was missing. Sean is a man’s man. He works as an electrician, surrounded by an industry that prizes brawn and heft. Sean’s father had died when he was young. Sean knew what an incredible bond can exist between a father and a son. For Sean, having his own son would help heal that wound. Two years after Libby was born, Priscilla became pregnant with Jacob. Their family would be complete.

WHEN ALL YOUR PLANS CHANGE

For some reason, nothing about her third pregnancy seemed organized. Priscilla had cravings this time–not normal pregnancy cravings, but intense, acute cravings. Once, in the middle of the night, it had to be cereal and cold milk. But the milk couldn’t be cool–it had to be icy, crunchy. She put the milk in the freezer before she ate the cereal.

A doctor confirmed that something was out of whack. Priscilla was diagnosed with gestational diabetes, a type of glucose imbalance that starts during pregnancy and affects about 4 percent of women. Priscilla knew the high sugar levels in her blood could be unhealthy for both her and her baby. If diabetes isn’t treated, a baby can have problems at birth–usually nothing serious, maybe jaundice or low blood sugar, but occasionally a baby can weigh much more than normal. Priscilla took insulin shots. Doctors reassured her all would be well.

Aside from the bruising, Jacob was born perfect and stayed on course his first year of life. He was an active little guy, gurgling and cooing strong and true. His checkups all showed health and vigor. Other than a slight tremor in one hand, all was well. Whenever Jacob concentrated, trying to pick something up, his hand would give a little shake. Nothing big. But Mom and Dad kept a watchful eye on it.

Jacob learned to walk right on schedule. He’d plow along, all boy, pressing forward to whatever he could grab. Sometimes he’d stop suddenly. Not a normal stop–more a stunt-man stop. It was like someone pulled a cord on him, jerking him back. Never quite seeing it happen, Priscilla wondered if one of the girls had pushed him down, good-naturedly, as siblings can do. But they hadn’t. No one was pushing him down.

One day, at a regular checkup, Priscilla relayed the news to her pediatrician hopefully, almost nonchalantly. This was nothing, wasn’t it? The doctor’s alarm caught Priscilla off guard. Jacob was scheduled for an emergency MRI the same day. He was rushed to the hospital and placed inside the giant horizontal tube for the test. But the MRI showed nothing. So Jacob went to a specialist. “Maybe a muscle disorder,” came the reply. “He’ll probably grow out of it.” Priscilla wanted to believe that. She says now that she should have asked more questions then–way more questions.

One month after that first round, Priscilla knew Jake’s condition involved something much greater than a muscle disorder. Always boy, Jake reached into the kitchen trash one day at home and cut his finger on a can. It required a few stitches–all part of growing up. After a tetanus shot, though, the chaos began. Seizure after seizure racked Jacob’s little body. Somehow the shot had acted as the tipping point for whatever had built up in his little system.

The seizures didn’t stop.

For days, Jacob was in and out of the emergency room. Nothing worked. Sean took care of the girls while Priscilla drove Jacob the three hours from their home in Bend, Oregon, to one of the larger hospitals in Portland.

On the first trip into the hospital, Priscilla watched her nearly two-year-old son take beautiful tiny steps. Her walking son, still on target for a life of running, jumping, just being the boy they’d hoped he’d be.

Those were the last steps Jacob took.

JUST FOR TODAY

Hospitals can be helpful places. Supportive. Caring. Healing. Miraculous.

Hospitals can also be frustrating.

After four days, Jacob was discharged. Tests showed nothing, even though Priscilla now had to carry her son back to the car. Her mom joined her. They planned to stay at a friend’s house for the night and drive back to Bend the next day. Thirty minutes from the hospital, on the long Interstate 205 bridge from Oregon to Washington, Jacob began having what are known as cluster seizures. With Jacob strapped in his car seat, Priscilla was unable to stop the car on the freeway bridge. They counted perhaps one hundred seizures, one right after another, blows landing on Jacob like the midrounds of a welterweight championship. Jacob screamed with each one. For a mother’s ears, Priscilla said, it was unimaginable.

They raced back to the hospital, but policy said since Jacob had just been discharged, he needed to follow admittance procedures again. Priscilla took him to the emergency room to wait. With Jacob having seizures on the hospital floor, Priscilla reached the doctor– the same doctor who had examined her child less than an hour earlier– by phone.

“You have to help us!” she said.

“Sorry,” the doctor said. “He’s not my patient anymore.”

Priscilla was livid. Jacob was given Valium in the emergency room. The family drove across the city to another hospital.

Says Priscilla of the experience: “He was never the same kid again.”

Jacob spent ten days in the next hospital. He had spinal taps, full workups, any test any doctor could think of. All results came back the same: inconclusive diagnosis. On February 22, during that tenday stint, Jacob celebrated his second birthday from his hospital bed.

“The hospital staff brought him a cake, which he couldn’t eat, and a little Elmo doll–which made him smile,” Priscilla said. “But it was just a yucky day.”

So they came home.

Present day. For a woman who once needed to plan everything, Priscilla no longer considers herself a planner. For more than a year now, Jacob has had ups and downs, but mostly downs. For a while, Jacob still crawled. He doesn’t crawl anymore. He has problems swallowing. He can’t reach or grasp anymore. He no longer shows interest in toys. It’s a progressive shutdown. The official diagnosis is “degenerative neuromuscular disorder of unknown origin.” Translation: something’s wrong; nobody knows what it is.

“Having a sick kid changes everything,” Priscilla says. “I have no control. We went into survival mode. We just try to get through every day now.”

One of the hardest parts is simply not knowing the future. Jacob has had such medical lows that his parents have planned his funeral twice. There are still doctor visits and neurologist visits and specialist visits. They recently visited the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, hoping for something concrete there. They found nothing. Some have even ventured to say that Jacob will outgrow this. But Priscilla says the family has held on to that belief for too long.

Some bright moments exist. Priscilla says everyday activities take on new meaning. Going to the grocery store, taking a walk with Sarah and Libby–she doesn’t take these things lightly. Priscilla and Sean’s marriage is tighter than it’s ever been. Jacob’s illness has made the couple go deep.

SMALL HOPE, SMALL BRIGHTNESS

Sparrow Clubs was held at Sarah’s elementary school the year before Jacob got sick. It took Priscilla awhile to fill out a reference form for Jacob because she was in such an emotional place. She didn’t want her daughters’ schools to be the host school for Jacob. If he didn’t make it, then her daughters would forever be known as “the sisters of that kid who died.” So Jacob was paired with a high school. The kids did penny drives and talent shows to raise money. Priscilla e-mailed the school with updates.

Christmas 2005 was the hardest time–but also the most poignant. Priscilla had always baked, decorated, made Christmas a big deal for her family, but this year she couldn’t. This Christmas felt neither joyous nor happy; it was just about getting through.

Somehow the kids at the high school found out. They arranged for a Santa to come to the house with gifts for everyone in the family. There were homemade crocheted scarves, toys for the kids, relaxation candles for the grownups–the Joves’ garage was literally full of presents. Everybody in the family was bawling. Somehow the tears helped.

“We were really feeling like we were going down,” Priscilla says of Christmas that year. “But they helped it be the best ever for our kids.”

Life continues for the Jove family. The hardest part is just not knowing what will happen.

Jacob has a new neurologist and more tests scheduled. The last one had simply told the family to keep Jacob comfortable until he dies.

But nobody accepts that.

“We’re still fighting,” Priscilla says. “If they don’t know what it is, then how do they know there’s no help available? We’re not giving up.”

Jacob’s face looked like it had gone twelve rounds. Bruised, battered, black-and-blue–this was no way for a newborn to spend his first few moments in the world.

“Nine pounds, eight ounces,” the scales read. The nurse repeated the information. Lying on the birthing bed, Priscilla Jove could hardly believe it. Her new son was huge–and he was three weeks early. But what did it matter? Aside from the severe bruising, Jacob checked out completely healthy. Her new son was perfect.

Priscilla had worried that maybe this pregnancy wouldn’t be as smooth as her first two. Labor had been quick this time–only fortyfive minutes. The drugs she had been given made pushing sudden and harsh. Jacob fought his way out like a boxer. He arrived glorious, wet, and triumphant, although a bit beat up. He would be tough, just like his dad, Sean Jove.

That Priscilla and Sean were having children at all was a miracle. Years earlier, when the couple lived in Los Angeles, they had been dubbed infertile. They had run the gamut of treatments. Hormone shots just made Priscilla crazy. She took them anyway, but in the end– after hot flashes, waiting, praying, hoping, money out the door–still nothing. One day, in desperation, she fell on her hands and knees before God and turned it all over to Him.

“Lord,” she said, “it has to be from You.”

Two months later she was pregnant.

Priscilla got prepared. If pregnancy, birth, and child rearing were about being organized, she wanted to get an A-plus. She scoured bookstores, devouring everything she could find. She made lists. She planned. She sorted. The couple’s first child, Sarah, was born right on schedule. Two years later, the details worked out perfectly again. Another daughter, Libby, arrived like clockwork.

The girls were bright, brilliant, beautiful. Priscilla and Sean were thrilled. Still, it felt like a member of the family was missing. Sean is a man’s man. He works as an electrician, surrounded by an industry that prizes brawn and heft. Sean’s father had died when he was young. Sean knew what an incredible bond can exist between a father and a son. For Sean, having his own son would help heal that wound. Two years after Libby was born, Priscilla became pregnant with Jacob. Their family would be complete.

WHEN ALL YOUR PLANS CHANGE

For some reason, nothing about her third pregnancy seemed organized. Priscilla had cravings this time–not normal pregnancy cravings, but intense, acute cravings. Once, in the middle of the night, it had to be cereal and cold milk. But the milk couldn’t be cool–it had to be icy, crunchy. She put the milk in the freezer before she ate the cereal.

A doctor confirmed that something was out of whack. Priscilla was diagnosed with gestational diabetes, a type of glucose imbalance that starts during pregnancy and affects about 4 percent of women. Priscilla knew the high sugar levels in her blood could be unhealthy for both her and her baby. If diabetes isn’t treated, a baby can have problems at birth–usually nothing serious, maybe jaundice or low blood sugar, but occasionally a baby can weigh much more than normal. Priscilla took insulin shots. Doctors reassured her all would be well.

Aside from the bruising, Jacob was born perfect and stayed on course his first year of life. He was an active little guy, gurgling and cooing strong and true. His checkups all showed health and vigor. Other than a slight tremor in one hand, all was well. Whenever Jacob concentrated, trying to pick something up, his hand would give a little shake. Nothing big. But Mom and Dad kept a watchful eye on it.

Jacob learned to walk right on schedule. He’d plow along, all boy, pressing forward to whatever he could grab. Sometimes he’d stop suddenly. Not a normal stop–more a stunt-man stop. It was like someone pulled a cord on him, jerking him back. Never quite seeing it happen, Priscilla wondered if one of the girls had pushed him down, good-naturedly, as siblings can do. But they hadn’t. No one was pushing him down.

One day, at a regular checkup, Priscilla relayed the news to her pediatrician hopefully, almost nonchalantly. This was nothing, wasn’t it? The doctor’s alarm caught Priscilla off guard. Jacob was scheduled for an emergency MRI the same day. He was rushed to the hospital and placed inside the giant horizontal tube for the test. But the MRI showed nothing. So Jacob went to a specialist. “Maybe a muscle disorder,” came the reply. “He’ll probably grow out of it.” Priscilla wanted to believe that. She says now that she should have asked more questions then–way more questions.

One month after that first round, Priscilla knew Jake’s condition involved something much greater than a muscle disorder. Always boy, Jake reached into the kitchen trash one day at home and cut his finger on a can. It required a few stitches–all part of growing up. After a tetanus shot, though, the chaos began. Seizure after seizure racked Jacob’s little body. Somehow the shot had acted as the tipping point for whatever had built up in his little system.

The seizures didn’t stop.

For days, Jacob was in and out of the emergency room. Nothing worked. Sean took care of the girls while Priscilla drove Jacob the three hours from their home in Bend, Oregon, to one of the larger hospitals in Portland.

On the first trip into the hospital, Priscilla watched her nearly two-year-old son take beautiful tiny steps. Her walking son, still on target for a life of running, jumping, just being the boy they’d hoped he’d be.

Those were the last steps Jacob took.

JUST FOR TODAY

Hospitals can be helpful places. Supportive. Caring. Healing. Miraculous.

Hospitals can also be frustrating.

After four days, Jacob was discharged. Tests showed nothing, even though Priscilla now had to carry her son back to the car. Her mom joined her. They planned to stay at a friend’s house for the night and drive back to Bend the next day. Thirty minutes from the hospital, on the long Interstate 205 bridge from Oregon to Washington, Jacob began having what are known as cluster seizures. With Jacob strapped in his car seat, Priscilla was unable to stop the car on the freeway bridge. They counted perhaps one hundred seizures, one right after another, blows landing on Jacob like the midrounds of a welterweight championship. Jacob screamed with each one. For a mother’s ears, Priscilla said, it was unimaginable.

They raced back to the hospital, but policy said since Jacob had just been discharged, he needed to follow admittance procedures again. Priscilla took him to the emergency room to wait. With Jacob having seizures on the hospital floor, Priscilla reached the doctor– the same doctor who had examined her child less than an hour earlier– by phone.

“You have to help us!” she said.

“Sorry,” the doctor said. “He’s not my patient anymore.”

Priscilla was livid. Jacob was given Valium in the emergency room. The family drove across the city to another hospital.

Says Priscilla of the experience: “He was never the same kid again.”

Jacob spent ten days in the next hospital. He had spinal taps, full workups, any test any doctor could think of. All results came back the same: inconclusive diagnosis. On February 22, during that tenday stint, Jacob celebrated his second birthday from his hospital bed.

“The hospital staff brought him a cake, which he couldn’t eat, and a little Elmo doll–which made him smile,” Priscilla said. “But it was just a yucky day.”

So they came home.

Present day. For a woman who once needed to plan everything, Priscilla no longer considers herself a planner. For more than a year now, Jacob has had ups and downs, but mostly downs. For a while, Jacob still crawled. He doesn’t crawl anymore. He has problems swallowing. He can’t reach or grasp anymore. He no longer shows interest in toys. It’s a progressive shutdown. The official diagnosis is “degenerative neuromuscular disorder of unknown origin.” Translation: something’s wrong; nobody knows what it is.

“Having a sick kid changes everything,” Priscilla says. “I have no control. We went into survival mode. We just try to get through every day now.”

One of the hardest parts is simply not knowing the future. Jacob has had such medical lows that his parents have planned his funeral twice. There are still doctor visits and neurologist visits and specialist visits. They recently visited the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, hoping for something concrete there. They found nothing. Some have even ventured to say that Jacob will outgrow this. But Priscilla says the family has held on to that belief for too long.

Some bright moments exist. Priscilla says everyday activities take on new meaning. Going to the grocery store, taking a walk with Sarah and Libby–she doesn’t take these things lightly. Priscilla and Sean’s marriage is tighter than it’s ever been. Jacob’s illness has made the couple go deep.

SMALL HOPE, SMALL BRIGHTNESS

Sparrow Clubs was held at Sarah’s elementary school the year before Jacob got sick. It took Priscilla awhile to fill out a reference form for Jacob because she was in such an emotional place. She didn’t want her daughters’ schools to be the host school for Jacob. If he didn’t make it, then her daughters would forever be known as “the sisters of that kid who died.” So Jacob was paired with a high school. The kids did penny drives and talent shows to raise money. Priscilla e-mailed the school with updates.

Christmas 2005 was the hardest time–but also the most poignant. Priscilla had always baked, decorated, made Christmas a big deal for her family, but this year she couldn’t. This Christmas felt neither joyous nor happy; it was just about getting through.

Somehow the kids at the high school found out. They arranged for a Santa to come to the house with gifts for everyone in the family. There were homemade crocheted scarves, toys for the kids, relaxation candles for the grownups–the Joves’ garage was literally full of presents. Everybody in the family was bawling. Somehow the tears helped.

“We were really feeling like we were going down,” Priscilla says of Christmas that year. “But they helped it be the best ever for our kids.”

Life continues for the Jove family. The hardest part is just not knowing what will happen.

Jacob has a new neurologist and more tests scheduled. The last one had simply told the family to keep Jacob comfortable until he dies.

But nobody accepts that.

“We’re still fighting,” Priscilla says. “If they don’t know what it is, then how do they know there’s no help available? We’re not giving up.”