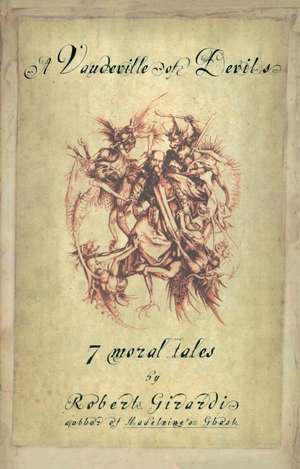

A Vaudeville of Devils

Autor Robert Girardien Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 1999

Meet Hans Otto Graebner as he lingers in the beach resort of Ostend, on the North Sea. Soon this haggard SS officer will be dispatched to perform the menial but necessary task of locating and assassinating a degenerate Belgian painter.

Join "The Dinner Party," where a man stands adrift in a distinctly Borgesian universe, somewhere at the end of time. It could be the Apocalypse or some ghoulish carnival. He's attending a feast at an anonymous mansion while the fall of Babylon is acted out around him, and he struggles to hold on to the faint remnants of his conscience while the world goes up in flames.

Turn to a search for "The Primordial Face," in which two expatriates, one of them mute, go diving for a mythological treasure at the bottom of the sea and wind up competing for the love of the obsessive expedition leader's young daughter.

And spend "Sunday Evenings at Contessa Pasquali's," where a man and a woman torture each other with indifference and affection and find that love can be born of terrible schemes.

With this volume, Robert Girardi illustrates a world that is both beautifully alluring and brilliantly sinister, where souls are lost and won on the simple weight of everyday decisions. Rich with history and irony, vastly entertaining and told in the timeless style of tales, fables, and myths, these meditations on morality remind us of the eternal human condition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 163.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 245

Preț estimativ în valută:

31.25€ • 32.72$ • 25.86£

31.25€ • 32.72$ • 25.86£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 01-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385333986

ISBN-10: 0385333986

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.56 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0385333986

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.56 kg

Editura: DELTA

Notă biografică

Robert Girardi is the author of three previous novels: Madeleine's Ghost, The Pirate's Daughter, and Vaporetto 13. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife and daughter. He can be reached by e-mail at lgirardi@aol.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Demons Tormenting Untersturmführer Hans Otto Graebner

A gang of prisoners worked along the strand in the rain, filling bomb craters from last night's air raid with rubble, rebuilding the walls of sandbags around the gun emplacements. The long barrels of the antiaircraft guns glistened black against the wet sky. There is nothing more dismal than a beach resort in winter: the hotels closed, their awnings furled; the concessions that sell lemon water and fried potatoes shuttered; the quayside brasseries boarded up against the hope of better days, dust gathering on the hips of the bottles, on the tin countertops. Doubly dismal is a beach resort in the middle of winter in the middle of a war.

At the far end of the pier the smashed casino still burned, soot darkening its white facade. A direct hit from the British Lancasters with incendiaries. I imagined the glossy rosewood and ivory roulette wheels reduced to ash, the teardrop chandeliers now melted chunks of blue glass in the charred remains of the interior and patted my pockets for a cigarette. The pack was empty. I'd smoked my last on the train down from Brussels. I approached one of the soldiers detailed to guard the work gang. He looked cold and bored; there would be no problem from that starving bunch today. When he saw the twin silver lightning bolts on the collar of my coat, he drew himself up and saluted smartly.

"What's your name, Private?" I gave him a hard, appraising look.

"Wurmler, sir!" he called out.

"Do you have a cigarette, Private Wurmler?"

"Yes, sir!" He fumbled in his pocket, produced a flat box of flimsy cardboard, and held it out to me.

"Relax, Wurmler," I said. "Why don't you have one yourself?"

He seemed surprised; then he unshouldered his rifle and rested it against the balustrade. The cigarettes were army issue, made from cheap Turkish tobacco captured during the invasion of Crete. We stood in silence for a moment, taking the harsh smoke into our lungs. I stared out at the gray water, the horizon lost in fog. A crazy scrawl of barbed wire straggled up the beach. A few abandoned changing cabins remained down there, half sunk in sand, now used to store wire spools and mining equipment. I tried to ignore the sharp pain in my knee. This dampness was not good for mending bones.

"What's it like here, Wurmler?" I said at last.

He looked puzzled. "You mean in Ostend, sir?"

"Yes, in Ostend."

"You know, it's not Berlin, sir."

"You're right," I said, attempting a smile. "It's not even Brussels."

He laughed at this, and I imagined him talking to his comrades later: Those fellows in the SS, they're not so bad. One of them even cracked a joke yesterday! A memorandum had come through headquarters last month regarding fraternization with soldiers of the regular army, which was to be encouraged whenever possible. We must dispel the counterproductive aura of snobbishness that has surrounded the corps and encourage the dissemination of National Socialist ideals was how Reichsmarschall Himmler had explained matters. I had my own reasons.

"Tell me, Wurmler," I said, leaning close. "How are the women in this town?"

Wurmler looked suspicious; he'd heard too many stories. "I'm a married man, sir," he said.

"Don't worry," I said. "We're not all saints in the SS, you know."

He hesitated, weighing the consequences. "There's a place where the men go." He lowered his voice. "Enlisted only, definitely not for officers. The whores are very ugly, skin and bones. Hell, officers need clean sheets and a little polite conversation before they drop their trousers, right?" He grinned. Now it was his turn to joke. I ignored the comment. A wet gust of wind blew off the water; two gulls fought for a scrap of something dead in the surf.

"Damn melancholy this time of year," I said, shivering. "I suppose things might get a little cheerier in July, August. The height of the season in the old days, yes?"

"Maybe, but you wouldn't be able to bathe in the water." Wurmler pointed out the wire on the beach. "We've got the whole place mined. In case the enemy decides to try something."

I nodded and tossed the bitter end of my cigarette to the shrapnel-chipped pavement and rubbed it out with the heel of my boot. "Good luck, Private Wurmler," I said. "Carry on."

He drew himself up again and saluted. "Heil Hitler!" he said with a little too much enthusiasm.

"Yes, Heil Hitler," I said, and limped off toward the row of forlorn beach hotels huddled beneath the rain in the distance.

A sandbag barrier ten meters high scaled the front of the famous Hôtel Continental des Bains. Fortified sentry posts flanked the front steps up which porters in livery had once carried the monogrammed luggage of the aristocracy. I remembered seeing a photograph of the Belgian king Leopold posed on those same steps, smiling with his family on a sunny day before the war. The hotel was now command headquarters for the military district of Ostend-Brugge. Staff officers of the Wehrmacht strode about the peach and red velvet lobby with papers in their hands, trying to look important.

Behind the front desk, a magnificent monstrosity of carved mermaids and seashells, they had set up a communications station. I handed my orders to a beefy, red-faced technical sergeant who seemed stuffed into his uniform like a sausage into its casing.

"I'm here to see Generaloberst von Falkenhausen," I said.

The technical sergeant unfolded my orders with thick fingers, frowned at the embossed seals stamped into the heavy paper, handed them back to me.

"You'll have to wait, sir," he said curtly. "The general is busy with military matters until late this afternoon."

I struggled to keep my temper. The hostility of von Falkenhausen and his staff to the political aims of the SS was well known in Berlin. The general was not a conscientious Nazi, but he was an excellent soldier, and the Führer still had a lingering respect for members of the old Prussian warrior caste. Of course, when the war was won and the Reich no longer needed such men, von Falkenhausen would have to watch his backside.

I waited for hours in an empty room attached to von Falkenhausen's suite on the sixth floor. A large dark patch on the faded peach carpet showed where the bed had been, smaller patches for the night tables. The only furnishings now were a single chair and a pile of old magazines. I sat in the chair for a while with a copy of Totenkampf and half read a cheery piece of propaganda about Feldmarschall Rommel's victories in Africa, then stood at the window and watched the light change over the water and tried to put a name to the uneasy feeling turning in my gut.

Political work didn't suit me: too many fine ideological distinctions, too much waiting. Waiting made my hands shake, my mouth go dry. Waiting gave me time to think about the Jewish painter Nussbaum, whom we'd arrested in Brussels two months ago in the garret where he'd been hiding. Another Jew had given up Nussbaum's hiding place for money. That was the one thing I'd learned since my reassignment to the Polizeidivision: There was always someone willing to sell someone else's skin for money.

Nussbaum, wearing only his socks and underwear, was eating sardines out of a tin with a palette knife when we kicked the door down. On the easel behind him, a large, unfinished canvas, a self-portrait showing the painter draped in a gray coat pinned with the yellow star, holding an identity card up to the viewer. A look of terror shone in his eyes in the self-portrait, as if he knew any minute someone was coming to haul him off for interrogation. Nice use of color, nice composition, a certain deft facility with the brush--and quite prophetic. But before I could get a better look, Sturmscharführer Stodal slashed the canvas lengthwise with a sharp dagger carried around just for that purpose, and Lemke and Groschen set about slashing everything else.

There must have been two hundred paintings stuffed into that garret, over a thousand drawings and prints, a lifetime's work. Nussbaum didn't move a muscle; no one laid a hand on him. It wasn't necessary; those paintings were the only reason he'd ever taken a breath upon the earth. He sat quietly, watching us destroy his life picture by picture. After a while big childish tears began to stream down his face, dropping to bead on the surface of the oil in the tin of sardines.

Later that night, as the last tattered bits of Nussbaum's work were fed to the blaze in the street, I'd gone with a whore, a fat streetwalker waddling around the serpentine paths in the Parc Royal. She was surprised that an officer of the SS wanted a tumble with her when he could easily have any woman in the city, but I gave her enough money not to think about the situation. We went to a dirty little hotel in the Rue d'Aix. It wasn't a very pleasant experience. I'd gone with a lot of whores lately. I couldn't say why.

Generaloberst Alexander von Falkenhausen's dachshund sat up on its hind legs on the Turkish carpet, begging for scraps from the remains of the general's lunch as I came through the double doors into his office. Another dachshund lay asleep, nose on its paws atop the general's vast mahogany Empire-style desk. The general himself squatted on the floor, a nice-looking pork cutlet dripping grease from his fingertips.

I clicked the heels of my boots together in the best Prussian style and saluted. "Untersturmführer Graebner reporting, Herr General!"

General von Falkenhausen grunted but did not look up. I stood at attention for some minutes while the dog gnawed at the pork and licked the general's fingers. From the adjoining room came the clatter of several typewriters and the hushed murmurings of the staff. A wide bay window overlooked the beach and the darkening water below. The sea was the color of raw oysters now, going to black over toward the horizon. My knee began to throb; I felt the regular beat of pain rising into my groin. At last the dog finished eating, and the general rose from the floor, adjusting his thick pince-nez spectacles. Hard light from the window gleamed dully off his bald head.

"Another SS officer in Belgium!" he announced loud enough to be heard in the next room. "Don't we suffer enough trouble from you idiots already?"

"This is not a permanent assignment, Herr General," I said. "I have come from Berlin on special detail. Reichsmarschall Himmler has charged my division with--"

"Yes, I know," General von Falkenhausen interrupted. "I am familiar with your orders."

"Very good sir."

He sighed, removed his spectacles, and wiped the lenses on a little piece of felt cloth. His booming voice seemed all out of proportion to his diminutive physical person. He was an odd-looking shriveled little man, about sixty, with a pronounced nose and large comical ears. There was something vaguely Oriental about his mannerisms; in fact, he bore a striking resemblance to the Hindu pacifist Gandhi.

Now I recalled a few facts from his dossier at headquarters: The general had spent nearly two decades in the Far East as the Kaiser's military representative. He had been stationed in Peking when the Boxers attacked the European compound in 1900, in Tokyo in 1904, when the news came through that the Japanese had destroyed the Russian fleet at Vladivostok, in Turkey during the Great War. Apparently all this contact with the yellow races had turned him into something of a Buddhist. His country estate in Silesia had recently acquired an ugly little Buddhist pagoda complete with a potbellied statue of that inscrutable deity, the whole arrangement photographed secretly last year by one of our agents posing as a gardener.

"Really, is this sort of operation necessary?" General von Falkenhausen replaced his spectacles now and squinted in my direction.

"I'm not sure what you mean, sir," I said.

"I mean, chasing down artists in their garrets and propping them up in front of firing squads! We're trying to win a war here! When will they realize that simple fact in Berlin? What will it be next, ballerinas, tightrope walkers, clowns? Yes, next Himmler will be arresting circus clowns for some imagined threat to National Socialism!"

I thought it best not to respond to this tirade. I was still standing at attention, and my knee began to burn like a hot coal. The battlefield does not make the best surgical theater; they hadn't put me back together quite right. Of course, in defense of the field surgeons, everything--tendons, muscles, cartilage--had been a mess of bone splinters and shrapnel. I had learned to walk again over the course of a two years' stay at the military hospital in Friedrichshafen. Just thinking about the doctors with their needles and absurd machines made the pain worse.

"Is something wrong, Untersturmführer Graebner?"

"No, Herr General," I said. "That is, my knee . . ."

General von Falkenhausen squinted through his spectacles at the decorations on my tunic.

"Ah, Knight's Cross, oak-leaf clusters!" he exclaimed. "You have been wounded in the field!" And the petulance of rank lifted like a bad cloud. Suddenly he was all solicitude. He called for a chair and, once I was comfortably installed, offered a cigarette from a platinum case. It was a private blend, wonderfully smooth, a world above Wurmler's miserable brand. A man's position in the hierarchy of the German Army may be measured by the quality of his cigarettes.

The general settled down in the great leather chair behind his desk and took the sleeping dachshund into his lap. The little dog woke up long enough to push its nose in a gap between the buttons of the general's jacket, gave out a contented snuffle, and went back to sleep.

"So, in which campaign were you wounded?" He lit his own cigarette and blew smoke at the high ceiling, decorated with bright frescoes of cherubim and nymphs at play.

"France, September 1940. I was with the Twenty-first SS-Panzergruppen. My machine hit a very powerful mine, packed with dynamite. The other lads made it up the hatch unscathed, but I was not so lucky." I smiled weakly. "Actually I think I was the only German wounded in the entire campaign."

General von Falkenhausen allowed himself a short chuckle, then grew serious.

"This political work, it's dirty, Graebner," he said. "No good for a soldier. I admit you seem like a decent fellow, not like most of the SS thugs Himmler sends down here, so I'll give you a piece of advice--Your mission is more sensitive than you think. The painter Ensor is a respected man in Belgium, and I mean by both the Walloons and the Flemish. Did you know that the king made a baron out of him before the war? My job is to keep the peace, to make certain that Belgian industry works at one hundred percent capacity in support of the German war effort!"

The general leaned back and stroked the head of the sleeping dachshund with two spidery fingers. Then he looked up, and the light caught his spectacles and made half-moon reflections on his sallow cheeks.

"So?"

"If you will allow me, sir," I said, "I'd like to try to explain the position of the corps in this matter."

He gave an assenting grunt.

I cleared my throat and paused a moment, trying to remember some of the exact words and phrases used in the propaganda manual.

"The Führer has called the Jews negative supermen," I began. "'Give me five hundred Jews,' he said, 'and I will take over Sweden in five years from the inside out. At the end of five years they will occupy every position of importance in the country--in industry, banking, and of course the arts.' Naturally there is no doubt as to the truth of the Führer's words, though if you ask me, sir, whether the takeover of Sweden would be accomplished through the cleverness of the Jews or the stupidity of the Swedes is a matter for conjecture. When we realize--"

The general interrupted with a quick chop of his hand. "Spare me the usual cant about the Jews, Graebner. Get to the point!"

"The point--"

"Wait." He interrupted again. "Tell me something. Why did they select you for this foolish duty? You're a soldier; what do you know about art?"

"I wasn't always a soldier, sir," I said. "Once I was an art student at the Prussian Academy of Arts and Architecture in Brandenburg. This was during the worst days of the Weimar corruption. Much of the art produced at the academy then was perverse, pro-Bolshevist, Jewish. Depictions of sexual acts, antiwar themes, portraits of cretins and dwarfs and so on. I left Brandenburg because the unwholesome un-German atmosphere made my head spin. In '33 I joined the party and became an art critic for Der Angriff, in which capacity I served until the commencement of hostilities. Then I enlisted in the corps and at my request was assigned to the armored division. After I was wounded, they reviewed my record and reassigned me to the Kulturkampf sector of the Polizeidivision."

"I see." The general nodded. "And how many other art critics do you suppose enlisted in the SS?" He asked this question in a very loud voice, and I heard a guffaw from someone in the adjoining room. I felt my ears going red.

"More than one might think, Herr General," I said, managing to keep my voice steady. "Perhaps because art is vital to the progress of National Socialism. The Führer himself has very often insisted on the political basis of all art. He has said that artistic anarchy is an incitement to political anarchy. Well, this is undoubtedly very true. Art is not merely a nice picture on a wall, a knickknack on a table. It is the very soul of the people. In shooting artists deemed degenerate by all common standards of decency, the Führer is showing conversely how important art and artists are to all of us."

When I finished this little speech, General von Falkenhausen drummed his fingertips on the dark wood of the desk and was silent. He removed his pince-nez spectacles again, rubbed the bridge of his nose, replaced them.

"You believe all that nonsense?" he said at last.

"I believe what I am told to believe, sir," I said.

"Let me see if I understand you," he said. "By shooting this Ensor fellow, you will be affirming his importance as an artist?"

"The work is unpleasant, I admit," I said. "I would rather be serving at the front with my old comrades, but in the interest of National Socialism--"

"Yes, yes!" The general stood out of his chair abruptly. The dachshund fell off his lap to the floor with a yelp. "If Himmler is determined to shoot another foolish artist, go ahead, shoot away, but I wash my hands of the whole affair! And I warn you, Ensor is different. Find some concrete excuse, produce evidence that he's been plotting against the Reich, that he's been making bombs in his basement, hiding spies. None of this vague talk about degenerate art! Fix this one carefully, or there will be hell to pay with the Belgians. Even a drop of one-half of one percent in the productivity of their armaments factories means German soldiers dead on the battlefield. Do you understand?"

General von Falkenhausen did not wait for my response. He went down on his hands and knees to retrieve both dachshunds from under the desk.

"Dismissed!" he called out from the shadowy recesses of this heavy piece of furniture. I struggled out of the chair, clicked the heels of my boots together, and limped out of the room and down the hall to the grand staircase.

Outside, along the strand, a winter dark was descending from

the east. The clouds had lifted off, and a sliver of moon hung over the sea, still vaguely phosphorescent as if the sun, sunk beneath

the waves, were now illuminating the ultimate depths. The men stood behind the steel shields of the antiaircraft guns, nervous, talking in low voices, dark shapes against the greater darkness, their eyes scanning the featureless horizon for the first sign of the enemy bombers, their ears straining for the first faint rumblings on the wind.

The Hôtel Kermesse, a gloomy little place on a quiet back street far from the beach, was the preferred stopping place for SS officers in Ostend. The thin walls of its small stuffy rooms were covered with peeling green wallpaper and garishly lit by amber cornucopia sconces that had been chic around 1920. At either end of the public area downstairs hung giant papier-mâché masks, relics of the pre-Lenten carnival, a bacchanal of public lewdness for which Ostend had become notorious in the years following the last war. From the hotel's narrow windows could be glimpsed the imposing edifice of the Belgian Thermal Institute for Hydropathic and Electrotherapy Treatment, a venerable medical establishment recently converted to less medical uses by the Gestapo.

A stoop-shouldered youth with a long, pimply face stepped up to me as I waited for the elevator. His greasy hair hung down across his eyes; encircling one sleeve of his mackintosh, the white and red armband of the VNV, the Flemish Fascist Party.

"Untersturmführer Graebner?"

I nodded, and the youth pulled himself up and delivered the full fascist salute. "Heil Hitler!"

"Heil Hitler," I said, "what do you want?"

"My name is Joop van Stijl, sir. I've been instructed by the local party chapter to act as your guide and interpreter." He showed me his orders, which had been routed through SS headquarters, Brussels. "Can I be of any assistance?"

I thought for a moment. "Do you know a decent restaurant that's not too far away? Presently I have some difficulty walking."

"German officers always eat in the dining room at the Hôtel Continental des Bains, sir," he said eagerly.

"So I understand," I said, "but tonight I prefer to dine elsewhere."

The youth scratched his greasy head. Out along the sidewalk a man in a long brown coat passed with the slow, jerky gait of a cripple, and I thought of myself. I didn't feel like enduring the snide comments of the Wehrmacht officers in the dining room at the continental as they stuffed their faces with Wiener schnitzel and carrots, I didn't feel like putting on a clean uniform, polishing my boots. Just then the long, low moan of the blackout sirens howled through the streets, and everywhere, in every house, there was a slow drawing down of blinds.

Sentimental French music played from the radio on the shelf above the bar. A dozen torpedo-shaped bottles of Dutch gin were set against a dusty mirror to the right of the ancient cash register of greening brass. A sad looking Flemish woman brought out bread, soft cheese, an iron crock of mussels steamed in white wine and garlic, a plate of fried potatoes, liter glasses of beer. The Belgian beer is sweet and heavy and very strong. I didn't realize how strong until I had downed a liter and a half and felt drunk. Despite the garlic, the mussels tasted of the sea.

"There will never be a shortage of mussels in Belgium," Joop said with his mouth full. "If we want mussels, all we have to do is go out at low tide. There they are, stuck to every rock. Of course in Germany I don't guess you have to worry about shortages!"

He was prattling on in such a way that the four other patrons of the little brasserie could not help overhearing every word: two old pensioners, hunched over fish stew at a table near the blacked-out window, and at the bar, drinking cognac, a small man and his large wife, her ass hanging off the sides of the stool. What if one of them were a member of the resistance? A disgruntled veteran of the Belgian Army of 1914? One telephone call to their friends, and I would be met by an assassin's bullet on the way back to the hotel.

"Shut your mouth, you little idiot!" I hissed at Joop. "This is not a lecture hall!"

The youth's eyes dropped to his plate; his pimpled face reddened. "Yes, of course, sir," he mumbled, "Excuse me." And he didn't say anything more. But after a while I found his droopy silence worse than his chattering.

"Tell me, Joop, how long have you been in the VNV?" I said. "You don't look old enough to be out of short pants."

"I'm eighteen, sir," he said, brightening. "The Führer says that one is never too young to serve the cause of National Socialism. I joined the VNV when I was fifteen, before the invasion of Poland."

"Good for you," I said.

"We Flemish are a Germanic people too, you know," he said, his eyes glittering a bit. "I heard last week they're starting up an SS detachment in Brussels for Flemish soldiers. Is it true, sir?"

"I think so," I said, though I knew nothing about the matter.

"I would join tomorrow"--he hesitated--"but my mother says I have to finish school first."

When we were done eating, the Flemish woman came and cleared away the plates. Joop waited until she had turned back to the kitchen; then he clapped his hands with a loud popping sound like gunfire that made me cringe.

"Gin, woman!" he called. "And two glasses!" The woman brought a bottle of gin in an unhurried fashion, and Joop pulled the cork out with his teeth and filled the glasses to the brim.

"To the German Reich!" He stood up, spilling gin down the sleeve of his coat. The pensioners at the table by the window looked over at this exclamation, then looked away quickly; the couple at the bar pretended not to hear. Joop drained off the gin in two swallows, sat down, and filled it up again.

"If you want to make an SS officer," I said, "you'll have to learn something very important."

"What's that, sir?" he said.

I crooked my finger, and he leaned forward. The light of the storm lantern directly above the table cast small shadows from the pimples on his face.

"Decorum," I whispered.

He nodded solemnly, as if I had just told him a great secret.

The gin was sweet and strong, like the beer. I drank two glasses and began to feel sick. Drinking was not good for me; we had very weak livers in my family. My father, who had been chief librarian of the municipal library in Luckenwalde, used to keep bottles of schnapps concealed behind certain little-read volumes concerning the history of Byzantine art in the back alcove of one of the less visited reading rooms. He later died of liver failure at the spa in Baden, where he had gone to take the curative waters.

The shudder of the waves reached us from the end of the street. A perfect night for submarine attacks, commando raids, little rubber rafts left on the beach the only sign that killers in black greasepaint were on the loose, anything that was down and dirty. My knee shot a few jolts of red-hot pain up my thigh and finally gave out. I had to lean against Joop's shoulder on the way back to the hotel, dragging my left leg after me like the body of a dead man.

"I don't mind at all, sir," Joop said, struggling to stay up under my weight. "It's an honor to help a war hero like you."

"I'm not a war hero," I said. "We hit a mine that we could have avoided, and I have spent most of the war so far in a military hospital."

Joop didn't say anything to this. The young prefer their illusions to the truth. When we reached the hotel, he stood back and gave me the fascist salute. "Good night, sir!" he said.

"Two things, Joop," I said before he turned away. "First, I want you to requisition a car for tomorrow. Do it on my authority."

"Yes, sir!" he said, pleased to be the bearer of such awesome power.

When I told him the second thing, he did not seem surprised.

Her skin showed a dark, oily brown, the color of the stock of a sharpshooter's rifle. Her lips were big and wet-looking, painted with sticky red lipstick. She wore a black coat with a moth-eaten fox collar; a ludicrous flowered hat caught her kinky hair. In her ears, large, barbaric golden hoops.

I stood in the doorway, in my undershirt and suspenders, gaping.

"Do you want me to come in or not?" she said in reasonably correct German.

I stepped aside and closed the door behind her and gaped some more.

"You're from the Belgian Congo?" I said.

She laughed. "I was born in Antwerp, in Borgerhout. Never been to Africa."

She threw her coat across the armchair in the corner, threw her hat on top of it, and began to take off her dress. Soon she was clad only in her brassiere, stockings, and half-slip. The black straps of her garter belt showed through the stained translucent fabric. She came across the room, big haunches wrinkling with each step, and put her arms around my neck.

"What's the matter, Captain?" she said. "Never sleep with a black whore before?"

"Actually, no," I said.

She sighed. "I can leave now if you want, and it will only cost you thirty francs for my trouble. But you're not going to find anyone else at this hour, at least anyone who will come to you here. And you know"--she took my hand and put it on her breast, which was warm to the touch and as large around as a gourd--"you might get used to my black skin. It's not so bad."

There was something about Ostend, about this whole stretch of coast. Its nights were raw and lonely; its damp air held a melancholy that got into your bones. Anything was better than being alone, than waiting for dawn to show pale and attenuated over the empty beach. I lay back on the bed and let the whore go to work. She took me in her mouth first and, when I was ready, straddled my thighs. I watched her black skin against my pale flesh with a morbid fascination. I thought of pictures I had seen of the African veld, of vast, undulating vistas that disappear into brown nothingness. I thought of the liquid pressure of one membrane against another, of the heavy feeling of her body warm as sand against my own. I put the Führer's injunctions against the mixing of the races completely out of my mind. At a certain moment she pushed off, took me in her mouth again, and finished me that way.

"Oh, I'm tired," she said when she could speak again. "How you make me work."

I opened my eyes and stared up at the old-fashioned plaster rosettes of the ceiling. A cool breeze blew against my shoulder; the heavy fabric of the blackout shade rustled against the window with a faint scraping sound. She propped herself up on one elbow, wiped her mouth on the back of her hand. Then she looked down at my knee.

"Someone really messed you up," she said. "What happened?"

"A dog bit me," I said.

"Mighty big dog, Captain," she said. "Can I touch it?"

I didn't say anything, and she ran her dark fingers gently over the pink landscape of scar tissue.

"That hurt?"

"Not really," I said. "Listen, you can stay a bit if you like. Rest before you go."

"Oh, you like me now?"

"Why not?"

She crawled up beside me and pulled the bedspread over her rump. "You got cigarettes?" she said.

"No," I said. "I smoked the last one on the train today."

"You got any canned meat?"

I almost laughed. "No," I said.

"Chocolate, perfume?"

"No."

She sat up and pushed out her bottom lip. "Then why should I stay?"

"Don't worry," I said. "I'll pay you something extra. A gratuity."

"All right."

She smiled and flopped back down, her large breasts pooling on the sheet, and we lay quietly for a while, saying nothing. Her hair smelled faintly sour, like milk about to go bad. The sea beat against the shore; clouds moved across the sliver of moon; the machinery of the war was silent.

In the morning, sun and wind. The pale, ephemeral light of late winter. From the window of my room I could see a fishing vessel stranded in the mudflats at low tide, lying heeled over on its side like a fat man on an operating table. I dressed in a fresh uniform, buckled on my pistol, and went downstairs.

Joop was waiting at the curb in front of the main entrance, leaning carefully against the fender of a ridiculous little three-wheeled Mochet cycle car. This diminutive vehicle, constructed out of canvas and wood and painted daffodil yellow, was barely large enough for two people sitting thigh to thigh.

"I'm sorry, sir," Joop said. "It was all I could requisition at such short notice." As it turned out, he had borrowed the Mochet from his cousin, a butcher in Brugge. "She's a bit slow. Of course Ostend isn't that big. We'll get where we're going!"

I was reluctant to fold myself into the cramped interior, but my knee had kept me up half the night, the whore had kept me up the other half, and I didn't feel like walking. Joop smiled as he opened the door for me. This morning he wore a pair of dark green aviator glasses, probably British. I couldn't see his eyes.

"Where are we going, sir?" he said.

I handed him the address on a small scrap of paper: 27 Rue de Flandres.

"But I know who lives there!" he exclaimed, peering down at the scrap of paper. "Everyone in Ostend knows. It's that crazy painter Ensor!"

"Not too loud, Joop."

He nodded, chastised, and put the Mochet in gear, and we lurched over the cobbles in the general direction of the sea at a speed so slow as not to merit the word. I felt the vibration of the tiny two-stroke engine in my joints. My teeth chattered.

"It's about time someone took care of that one," Joop called over the burp of the engine. "He's always been crazy. Since my father was a kid. Have you ever seen any of his paintings?"

"Yes," I said. "In the show of degenerate art at the Archäologisches Institut in Munich in '37."

"The man's paintings are crazy, full of skeletons and crazy people! Once he put a picture up for sale for only three hundred francs in the Kursaal. It was up for a whole year, and no one would buy it. Old Ensor got so mad he came down one day and cut it out of its frame and made a rug out of it, which he put at the front door to his store for people to walk on. He's completely crazy!"

We wound through narrow alleys clotted with garbage. The stink of brine hung heavy in the air. The Mochet's bicycle-sized tires took each dip and cobble like a crater and sent jolts of pain running up my leg. After about ten minutes of this torture we turned a corner into a large square jammed with horse carts and many drab-looking Belgians, some of them wearing wooden sabots on their feet. A crowd was gathered before a large open-fronted building constructed like a railway station out of iron girders and glass that appeared to be a fish market. We passed steaming heaps of white-winged skates fresh from the surf, oysters and clams on beds of shaved ice, lobsters in wooden barrels, tubs full of eels, piles of big steely-flanked groupers and mackerels, their scales shining like armor, their big red eyes turned toward heaven in lifeless accusation.

"I'm sorry, sir," Joop said. "The Minque is packed today. The fishing boats came in this morning." He squeezed the bulb of a little brass horn attached to the steering column and yelled obscenities in Flemish out the window. The crowds shifted sluggishly in our path, and we bumped across the square and turned up a little street that seemed to rise straight up into the sky. This street, so cheery it could have belonged to another city altogether, was flooded with peculiar silvery light reflected from the water and the dunes just over the rise.

"The Ensors have always been crazy," Joop said now. "The father, he was a drunkard; his wife used to lock him up in his room at night so he wouldn't run out and drink himself to death. And there was an aunt who used to take a bird in a cage out walking along the Digue. Said it needed air. Perhaps . . ." He grew pensive for a moment; then he snapped his fingers. "Perhaps they are Jews!"

"James Ensor is a Roman Catholic," I said quietly.

Joop seemed disappointed. He pulled the Mochet over to the curb halfway up the street and stopped before a tidy little storefront shaded with a red and white striped awning. A gold-lettered sign above the door read gallerie ensor--cocquillages--chinoiseries--objets d'art.

"I've got a hammer in the back," Joop said. "I can smash the window right away if you want. Or I can call some of the boys and we'll really tear the place apart; it wouldn't be a problem for us!"

"No," I said. "For the moment this is a reconnaissance mission."

Joop gestured to a row of tall windows on the second floor. "The old man lives up there. You've got to go through the shop. But don't try to buy anything; nothing's for sale!"

I extricated myself from the cycle car with some difficulty and stepped over to examine the shopwindow. A strange assortment of objects resided behind the thick glass: shells of all shapes and sizes; bulbous carnival masks; rows of porcelain-headed Chinese dolls; string puppets of devils and angels; delicate branches of coral; mechanical harlequins and ballerinas that could play the mandolin or dance at a turn of the key; silk fans painted with Oriental themes; the figurehead of a ship carved in the likeness of a red Indian. And presiding over everything, the mummified body of a monstrous creature, half monkey, half fish, suspended in a crenellated wicker cage.

I stood staring at this bizarre assemblage for a few minutes, then became aware of my own reflection staring back at me. There I was, a sharp-chinned bitter-looking fellow with colorless eyes and thin lips, a skull wearing the peaked skull-emblazoned cap of the SS. A man I would not want to meet alone in a dark street at night.

A bell tinkled from deep within the shadowy interior as I stepped across the threshold. Once inside, I found myself surrounded by the same sort of objects crowded into the window. For some reason a bright shell, roughly the size of a potato, attracted my eye; its glossy blue surface was covered with red blotches like stars, its opening showed a tender pink color that made me think of the folds of a woman's sex. Without thinking, I lifted the shell and held it to my ear.

"If you close your eyes and listen," a man's voice said in French, "you will hear the music the ocean makes off the coast of Java."

I dropped the shell and spun around on the heels of my boots. A thin, bent old man wearing a tattered red fez and a butler's striped waistcoat stood smiling on the other side of the counter at the far end of the room. A bushy white beard and mustache engulfed the bottom half of his face.

"I am looking for the painter James Ensor," I said in German.

"Monsieur Ensor does not come down from upstairs much these days," the old man replied in French. "He says he has rheumatism, but if you ask me, he's a little . . ." He tapped his forehead with two fingers.

"I must see him immediately," I said, putting all the authority of the Reich into my voice. "I am Untersturmführer Graebner of the SS. I have come all the way from Brussels, and I have no time to waste!"

The old man wagged his head, the tassel of his fez brushing sadly against his ear. "Very well," he said. "Follow me."

I followed him through a door behind the counter and up a narrow staircase into a large, airy first-floor parlor as crammed with artistic work as a small museum..

"Please wait here," he said. "I will tell Monsieur Ensor that you have come to see him."

He went through a pair of double doors into the next room. I lowered myself into a red chair and waited. The sun had risen high above the dunes, and yellow light streamed in through a row of floor to ceiling windows. From somewhere came the faint droning of an insect. A morbid Louis XV clock surmounted by a figure of Death the Reaper ticked loudly from the fireplace mantel. The second hand, a scythe made of carved bone, swept past the hours marked by tiny ivory skulls. After a while, I got up and paced the floor, unaccountably nervous. Every bit of wall space here was covered with framed pictures of one kind or another--all obviously executed by the same hand. I quickly counted about forty substantial oil paintings and did not bother to count the colored lithographs, etchings, and drawings in chalk, Conté crayon, and pencil.

I stopped my pacing to study a few canvases, looking for evidence of overt anti-German sentiments. Instead I saw a woman eating oysters; two naked children alone in a brown and yellow bedroom; a group of skeletons beating a hanging man with broom handles; a still life in which both dead fish and onions looked oddly alive; more skeletons warming themselves before a stove; skeletons fighting over a herring; a young man with a beard and mustache wearing a woman's hat against a background of carnival masks; the same young man sitting impassively in a chair while demons swirled and plucked all around him.

These paintings, at once sinister and lighthearted, were rendered in a bewildering, crude manner but composed of such astonishing colors I did not want to take my eyes from them. They made me think of dreams I had forgotten, that vanish upon waking. They made me think of diamond rings on the fingers of a beautiful woman lying dead in her coffin, which is to say of melancholy itself.

At that moment the double doors swung open, and an old man wearing a starched wing collar and black dress coat entered the parlor. It took a second look to realize this was the same old man who had greeted me downstairs; he had merely exchanged his ridiculous fez and butler's waistcoat for more formal attire. He bowed stiffly from the waist.

"I am James Ensor," he said in proper German. "How may I help you?"

"What sort of game is this?" I said, starting to get angry.

The old man seemed startled by my reaction. "I don't know what you're talking about--"

"Stop your lies!" I screamed. "You go in there, change your clothes, and claim to be someone else? I am not an idiot! I am an officer of the SS!"

I thought the old man was going to burst into tears. His lip trembled; his eyes grew moist. "You see, it is a sort of game," he said in a small voice. "I am James Ensor, you know. But servants are so hard to come by these days that I decided to become my own butler. I thought it would amuse people. I do enjoy amusing people, playing games. You needn't take it so seriously."

"I have come on very serious business," I said, controlling my anger.

"Oh?" I thought I saw Ensor shudder. "However before we discuss anything so serious, may I offer you a little apéritif!"

"Absolutely not," I said, but he hurried into the next room and returned with a bottle of Ricard and two delicate crystal glasses. He set the glasses on a small table and half filled them with the Ricard, which looked like liquid gold in the sunlight.

"Please, join me, Herr Offizier," he said, gesturing with the bottle.

"I'll get to the point," I said, ignoring him. "Your artwork has been deemed counterproductive to the aims of National Socialism. I have been sent from Berlin with specific instructions. First, we demand that you cease all artistic output immediately. Second, I have been given the authority to seize and destroy any works which in my opinion do not fit comfortably within the parameters of acceptable art as laid down by the Führer. If you resist my attempts in any way, you will be shot." I patted my holster for emphasis. "Is that clear?"

Ensor sighed and picked up his glass of Ricard with a trembling hand. I watched the bones in his throat working as he swallowed the alcohol.

"I have been waiting for this visit since 1937," he said. "My friend Nolde wrote me a letter from Germany. Do you know Nolde?"

"Emil Nolde the painter?"

"Yes."

"Exactly my point. Emil Nolde is a degenerate. The Führer has declared him an enemy of National Socialism."

"You call Nolde an enemy"--Ensor made a weak gesture--"but nevertheless, he is the greatest painter alive in Germany today. 'James, they have forbidden me to paint, they have taken my paintings and burned them'--this is what he wrote in his letter in bright blue ink stained with tears. You see, I am not like Nolde. I am a very old man, and I do not really paint any longer. Yes, these are my paintings. Many of them have hung in the same place in this room for fifty years. They are like old friends to me. But I suppose even old friends die and are buried in the ground and are seen no more. Destroy them if you must."

Something about Ensor's eyes just now reminded me of Nussbaum, and I did not want to see them looking at me. I turned quickly to the nearest canvas, a realistic work in red and brown that showed a man sitting in an empty room at a table upon which rested a clear bottle of gin. A woman carrying a stick was entering the room or leaving it; the painting was completely inoffensive except for the fact that both the man and the woman hid their faces behind grotesque carnival masks.

"Do you like the painting?" Ensor said hopefully.

"Very strange," I said. "Possibly degenerate."

"That can't be," Ensor said. "It is only a painting of two people wearing masks."

"Yes, I see that, but why?"

"It is the way I felt at the time I painted it. I was young and disillusioned and became convinced that no one in the world was showing his true face. Now that I am old, I know that no one has a true face to show."

This was exactly the sort of obfuscating claptrap I had expected. Did not the Führer himself refer to artists as consummate liars, as manufacturers of lies?

"Do you have other paintings?" I said.

Ensor nodded, helplessly.

"Better see everything."

I followed the painter through the double doors into his studio, cluttered with more carnival junk--dolls, puppets, masks, shells. But there was only one painting here of any significance: A gigantic canvas done in a vivid expressionistic style occupied the entire wall at the opposite end of the room. I stared up at this huge work, more and more bewildered, my eyes running wildly across its surface from one end to the other.

"There it is," Ensor whispered in my ear. "My masterpiece. I painted it when I was twenty-eight or twenty-nine, I can't remember exactly. Some days I sit and look at it for hours, marveling. It is hard for me to believe I actually painted such a work. Of course, if we live long enough, we become strangers even to ourselves."

The painting showed a vast parade of humanity of every description--I say jugglers, politicians, clowns, greengrocers, priests, mechanics, sailors, thieves, men, women, children--everyone wearing carnival masks. Sharpsters played at three-card monte in one corner; in the middle ground a mustachioed military band banged away on tinny-looking instruments, bright fraternal banners waving above their heads. In the corner closest to me, Death, wearing a green top hat and a green cravat, seemed caught up in the fun. And there, at the distant center of all the hubbub, astride a donkey, His head encircled by a great orange halo, Jesus Christ Himself blessed the multitudes.

For a long minute I didn't know what to think. This painting was grotesque and harmonious, foolish and wise, beautiful and ugly--all at the same time. The wealth of detail was so great a week of looking would not have revealed all there was to reveal. I had never seen anything so startling put on canvas by any artist. I felt dizzy; my knee sent a quick pulse of pain to my spine.

"You look tired," Ensor said. "And the painting can be quite overwhelming. I myself find that I cannot contemplate it standing up. Of course a little music softens the effect."

He pushed a paint-splattered armchair in my direction, and I dropped onto the cushion. Then he sat down at the bench of a harmonium positioned directly beneath the painting and began to pump the foot pedals to get the wind up. At last he released the ivory-handled stops, touched his hands lightly to the keys, and the music came. The soft, old-fashioned melody brought to mind the lament of a fairground calliope heard floating in the distance on an obscure afternoon lost in the past; then the hushing of the wind through the lindens in the park near our house where my sister and I used to fly kites, before she drowned in the lake at Trier. I remembered now, for the first time in twenty-five years, the aimless drift of a toy sailboat across the dark surface of the lake in the moment after the water had closed over her head forever. And I felt a terrible sadness when I thought of the long succession of days between then and now, a dull confusion at the man I had become.

"What are you thinking of?" The painter lifted his hands from the keys.

"My childhood," I said without hesitation. "In Luckenwalde."

"Once when I was very young," he said in a low voice, "lying in my cradle just after sunset, a large black seabird greedy for the light of our lamps flew through the open window and smashed into my cradle. I remember this very clearly. He flapped around the bedroom, smashing into the walls, the ceiling, shrieking and dripping blood on everything. I can still see his mad yellow eyes. I was frozen with terror, too terrified to scream for my mother. I have never forgotten this terrible incident. I have never forgotten that some terrible black thing can find me wherever I live, whenever it wants to. And I have never felt safe, not even with all the doors and windows locked and bolted."

He smiled gently to himself, turned back to the harmonium, and continued to play. The hollow echoing of the music made me feel drowsy, and I closed my eyes and felt myself sinking into a green ocean warm as piss, sinking to the utter darkness at the bottom. When I opened my eyes again, it was late afternoon, and I realized I had been asleep for a long time. The light was different coming in through the tall windows, and the huge painting looked different in this light, as if it had changed subtly with each passing hour of the day. Now Ensor sat across from me with a drawing board across his knees and a collection of colored chalks on the workbench at his right hand.

"What is your full name and rank?" he said.

"SS-Untersturmführer Hans Otto Graebner," I said, struggling to pull myself out of the chair.

"I have drawn a picture of you while you were sleeping," the painter said. "I just want to put the title on the bottom." He wrote very carefully, spelling out the words to himself, and when he was done, he took the picture off the board, rolled it into a tube, and tied it with a piece of brown string.

"This is for you," he said, and handed me the rolled-up picture. Then he helped me out of the chair, and together we left the studio and went through the large parlor hung with paintings to the top of the stairs.

"I do not go out much anymore," he said. "Especially in these evil times. Of course you may come and visit me again whenever you like."

I could think of nothing else to say. Ensor patted me on the shoulder in a fatherly manner, and I went down the stairs and out into the street. A strong wind blew from the north; it was quite cold. Joop had fallen asleep behind the wheel of his cousin's cycle car, drool trickling down the pimples on his chin.

"Hey! Wake up!" I put my boot against the door and rocked the vehicle back and forth.

Joop woke with a start, blinking his eyes. "I'm sorry, sir," he managed. "I fell asleep. How did it go with Ensor? Do you want me to bring the boys over? Mess the place--"

"That won't be necessary," I interrupted. "You can tell your friends in the VNV not to trouble themselves about Ensor. He's dead."

Joop blinked up at me, surprised. "But that can't be true. Just last week, I saw him walking along the Digue--" He stopped himself. "Did you--did--" His lower lip trembled; suddenly his voice sounded frightened.

I brought my fist down on the canvas top with a heavy thump. "Get out of here!" I shouted. "Now!"

Joop didn't need to be told twice. I stood back and watched the cycle car wobble down the hill and disappear around the corner of the Rue de l'Ouest. When the last echo of the engine died away, I turned to face the wind and limped up the slight rise to the top of the street. Just below, the cobbles gave way to a shingle road that disappeared among the dunes. Down there, beyond the barbed-wire perimeter, saw grass grew on the roofs of abandoned fishermen's cottages. The copper steeple of an old church shone red and gold in the sunset. Beyond everything the sea flexed like a muscle against the shore.

I untied the string and unrolled the picture that Ensor had made. There I was, asleep in the chair in his studio, oblivious, surrounded by a collection of demons and other fantastic creatures who were in the process of tormenting me. One demon with an ass for a face plucked almost tenderly at my sleeve; one with a penis-nose and giant bat wings raked his long teeth through my blond hair; another sat perched on my leg, sharp claws digging into my knee.

I studied the picture for some time. Yes, I thought, he has captured a good likeness; he has got it exactly right. I rolled the picture carefully, tied it with the string again, and began the long, painful walk back to the hotel through the fading light.

In 1942 the Belgian painter James Ensor heard a report of his own death over the radio from the BBC in London. The report was false, of course, but widely believed. He survived the war by five years and died in bed at the age of eighty-nine. The Entry of Christ into Brussels, generally considered his masterpiece, is now part of the collection of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

From the Hardcover edition.

A gang of prisoners worked along the strand in the rain, filling bomb craters from last night's air raid with rubble, rebuilding the walls of sandbags around the gun emplacements. The long barrels of the antiaircraft guns glistened black against the wet sky. There is nothing more dismal than a beach resort in winter: the hotels closed, their awnings furled; the concessions that sell lemon water and fried potatoes shuttered; the quayside brasseries boarded up against the hope of better days, dust gathering on the hips of the bottles, on the tin countertops. Doubly dismal is a beach resort in the middle of winter in the middle of a war.

At the far end of the pier the smashed casino still burned, soot darkening its white facade. A direct hit from the British Lancasters with incendiaries. I imagined the glossy rosewood and ivory roulette wheels reduced to ash, the teardrop chandeliers now melted chunks of blue glass in the charred remains of the interior and patted my pockets for a cigarette. The pack was empty. I'd smoked my last on the train down from Brussels. I approached one of the soldiers detailed to guard the work gang. He looked cold and bored; there would be no problem from that starving bunch today. When he saw the twin silver lightning bolts on the collar of my coat, he drew himself up and saluted smartly.

"What's your name, Private?" I gave him a hard, appraising look.

"Wurmler, sir!" he called out.

"Do you have a cigarette, Private Wurmler?"

"Yes, sir!" He fumbled in his pocket, produced a flat box of flimsy cardboard, and held it out to me.

"Relax, Wurmler," I said. "Why don't you have one yourself?"

He seemed surprised; then he unshouldered his rifle and rested it against the balustrade. The cigarettes were army issue, made from cheap Turkish tobacco captured during the invasion of Crete. We stood in silence for a moment, taking the harsh smoke into our lungs. I stared out at the gray water, the horizon lost in fog. A crazy scrawl of barbed wire straggled up the beach. A few abandoned changing cabins remained down there, half sunk in sand, now used to store wire spools and mining equipment. I tried to ignore the sharp pain in my knee. This dampness was not good for mending bones.

"What's it like here, Wurmler?" I said at last.

He looked puzzled. "You mean in Ostend, sir?"

"Yes, in Ostend."

"You know, it's not Berlin, sir."

"You're right," I said, attempting a smile. "It's not even Brussels."

He laughed at this, and I imagined him talking to his comrades later: Those fellows in the SS, they're not so bad. One of them even cracked a joke yesterday! A memorandum had come through headquarters last month regarding fraternization with soldiers of the regular army, which was to be encouraged whenever possible. We must dispel the counterproductive aura of snobbishness that has surrounded the corps and encourage the dissemination of National Socialist ideals was how Reichsmarschall Himmler had explained matters. I had my own reasons.

"Tell me, Wurmler," I said, leaning close. "How are the women in this town?"

Wurmler looked suspicious; he'd heard too many stories. "I'm a married man, sir," he said.

"Don't worry," I said. "We're not all saints in the SS, you know."

He hesitated, weighing the consequences. "There's a place where the men go." He lowered his voice. "Enlisted only, definitely not for officers. The whores are very ugly, skin and bones. Hell, officers need clean sheets and a little polite conversation before they drop their trousers, right?" He grinned. Now it was his turn to joke. I ignored the comment. A wet gust of wind blew off the water; two gulls fought for a scrap of something dead in the surf.

"Damn melancholy this time of year," I said, shivering. "I suppose things might get a little cheerier in July, August. The height of the season in the old days, yes?"

"Maybe, but you wouldn't be able to bathe in the water." Wurmler pointed out the wire on the beach. "We've got the whole place mined. In case the enemy decides to try something."

I nodded and tossed the bitter end of my cigarette to the shrapnel-chipped pavement and rubbed it out with the heel of my boot. "Good luck, Private Wurmler," I said. "Carry on."

He drew himself up again and saluted. "Heil Hitler!" he said with a little too much enthusiasm.

"Yes, Heil Hitler," I said, and limped off toward the row of forlorn beach hotels huddled beneath the rain in the distance.

A sandbag barrier ten meters high scaled the front of the famous Hôtel Continental des Bains. Fortified sentry posts flanked the front steps up which porters in livery had once carried the monogrammed luggage of the aristocracy. I remembered seeing a photograph of the Belgian king Leopold posed on those same steps, smiling with his family on a sunny day before the war. The hotel was now command headquarters for the military district of Ostend-Brugge. Staff officers of the Wehrmacht strode about the peach and red velvet lobby with papers in their hands, trying to look important.

Behind the front desk, a magnificent monstrosity of carved mermaids and seashells, they had set up a communications station. I handed my orders to a beefy, red-faced technical sergeant who seemed stuffed into his uniform like a sausage into its casing.

"I'm here to see Generaloberst von Falkenhausen," I said.

The technical sergeant unfolded my orders with thick fingers, frowned at the embossed seals stamped into the heavy paper, handed them back to me.

"You'll have to wait, sir," he said curtly. "The general is busy with military matters until late this afternoon."

I struggled to keep my temper. The hostility of von Falkenhausen and his staff to the political aims of the SS was well known in Berlin. The general was not a conscientious Nazi, but he was an excellent soldier, and the Führer still had a lingering respect for members of the old Prussian warrior caste. Of course, when the war was won and the Reich no longer needed such men, von Falkenhausen would have to watch his backside.

I waited for hours in an empty room attached to von Falkenhausen's suite on the sixth floor. A large dark patch on the faded peach carpet showed where the bed had been, smaller patches for the night tables. The only furnishings now were a single chair and a pile of old magazines. I sat in the chair for a while with a copy of Totenkampf and half read a cheery piece of propaganda about Feldmarschall Rommel's victories in Africa, then stood at the window and watched the light change over the water and tried to put a name to the uneasy feeling turning in my gut.

Political work didn't suit me: too many fine ideological distinctions, too much waiting. Waiting made my hands shake, my mouth go dry. Waiting gave me time to think about the Jewish painter Nussbaum, whom we'd arrested in Brussels two months ago in the garret where he'd been hiding. Another Jew had given up Nussbaum's hiding place for money. That was the one thing I'd learned since my reassignment to the Polizeidivision: There was always someone willing to sell someone else's skin for money.

Nussbaum, wearing only his socks and underwear, was eating sardines out of a tin with a palette knife when we kicked the door down. On the easel behind him, a large, unfinished canvas, a self-portrait showing the painter draped in a gray coat pinned with the yellow star, holding an identity card up to the viewer. A look of terror shone in his eyes in the self-portrait, as if he knew any minute someone was coming to haul him off for interrogation. Nice use of color, nice composition, a certain deft facility with the brush--and quite prophetic. But before I could get a better look, Sturmscharführer Stodal slashed the canvas lengthwise with a sharp dagger carried around just for that purpose, and Lemke and Groschen set about slashing everything else.

There must have been two hundred paintings stuffed into that garret, over a thousand drawings and prints, a lifetime's work. Nussbaum didn't move a muscle; no one laid a hand on him. It wasn't necessary; those paintings were the only reason he'd ever taken a breath upon the earth. He sat quietly, watching us destroy his life picture by picture. After a while big childish tears began to stream down his face, dropping to bead on the surface of the oil in the tin of sardines.

Later that night, as the last tattered bits of Nussbaum's work were fed to the blaze in the street, I'd gone with a whore, a fat streetwalker waddling around the serpentine paths in the Parc Royal. She was surprised that an officer of the SS wanted a tumble with her when he could easily have any woman in the city, but I gave her enough money not to think about the situation. We went to a dirty little hotel in the Rue d'Aix. It wasn't a very pleasant experience. I'd gone with a lot of whores lately. I couldn't say why.

Generaloberst Alexander von Falkenhausen's dachshund sat up on its hind legs on the Turkish carpet, begging for scraps from the remains of the general's lunch as I came through the double doors into his office. Another dachshund lay asleep, nose on its paws atop the general's vast mahogany Empire-style desk. The general himself squatted on the floor, a nice-looking pork cutlet dripping grease from his fingertips.

I clicked the heels of my boots together in the best Prussian style and saluted. "Untersturmführer Graebner reporting, Herr General!"

General von Falkenhausen grunted but did not look up. I stood at attention for some minutes while the dog gnawed at the pork and licked the general's fingers. From the adjoining room came the clatter of several typewriters and the hushed murmurings of the staff. A wide bay window overlooked the beach and the darkening water below. The sea was the color of raw oysters now, going to black over toward the horizon. My knee began to throb; I felt the regular beat of pain rising into my groin. At last the dog finished eating, and the general rose from the floor, adjusting his thick pince-nez spectacles. Hard light from the window gleamed dully off his bald head.

"Another SS officer in Belgium!" he announced loud enough to be heard in the next room. "Don't we suffer enough trouble from you idiots already?"

"This is not a permanent assignment, Herr General," I said. "I have come from Berlin on special detail. Reichsmarschall Himmler has charged my division with--"

"Yes, I know," General von Falkenhausen interrupted. "I am familiar with your orders."

"Very good sir."

He sighed, removed his spectacles, and wiped the lenses on a little piece of felt cloth. His booming voice seemed all out of proportion to his diminutive physical person. He was an odd-looking shriveled little man, about sixty, with a pronounced nose and large comical ears. There was something vaguely Oriental about his mannerisms; in fact, he bore a striking resemblance to the Hindu pacifist Gandhi.

Now I recalled a few facts from his dossier at headquarters: The general had spent nearly two decades in the Far East as the Kaiser's military representative. He had been stationed in Peking when the Boxers attacked the European compound in 1900, in Tokyo in 1904, when the news came through that the Japanese had destroyed the Russian fleet at Vladivostok, in Turkey during the Great War. Apparently all this contact with the yellow races had turned him into something of a Buddhist. His country estate in Silesia had recently acquired an ugly little Buddhist pagoda complete with a potbellied statue of that inscrutable deity, the whole arrangement photographed secretly last year by one of our agents posing as a gardener.

"Really, is this sort of operation necessary?" General von Falkenhausen replaced his spectacles now and squinted in my direction.

"I'm not sure what you mean, sir," I said.

"I mean, chasing down artists in their garrets and propping them up in front of firing squads! We're trying to win a war here! When will they realize that simple fact in Berlin? What will it be next, ballerinas, tightrope walkers, clowns? Yes, next Himmler will be arresting circus clowns for some imagined threat to National Socialism!"

I thought it best not to respond to this tirade. I was still standing at attention, and my knee began to burn like a hot coal. The battlefield does not make the best surgical theater; they hadn't put me back together quite right. Of course, in defense of the field surgeons, everything--tendons, muscles, cartilage--had been a mess of bone splinters and shrapnel. I had learned to walk again over the course of a two years' stay at the military hospital in Friedrichshafen. Just thinking about the doctors with their needles and absurd machines made the pain worse.

"Is something wrong, Untersturmführer Graebner?"

"No, Herr General," I said. "That is, my knee . . ."

General von Falkenhausen squinted through his spectacles at the decorations on my tunic.

"Ah, Knight's Cross, oak-leaf clusters!" he exclaimed. "You have been wounded in the field!" And the petulance of rank lifted like a bad cloud. Suddenly he was all solicitude. He called for a chair and, once I was comfortably installed, offered a cigarette from a platinum case. It was a private blend, wonderfully smooth, a world above Wurmler's miserable brand. A man's position in the hierarchy of the German Army may be measured by the quality of his cigarettes.

The general settled down in the great leather chair behind his desk and took the sleeping dachshund into his lap. The little dog woke up long enough to push its nose in a gap between the buttons of the general's jacket, gave out a contented snuffle, and went back to sleep.

"So, in which campaign were you wounded?" He lit his own cigarette and blew smoke at the high ceiling, decorated with bright frescoes of cherubim and nymphs at play.

"France, September 1940. I was with the Twenty-first SS-Panzergruppen. My machine hit a very powerful mine, packed with dynamite. The other lads made it up the hatch unscathed, but I was not so lucky." I smiled weakly. "Actually I think I was the only German wounded in the entire campaign."

General von Falkenhausen allowed himself a short chuckle, then grew serious.

"This political work, it's dirty, Graebner," he said. "No good for a soldier. I admit you seem like a decent fellow, not like most of the SS thugs Himmler sends down here, so I'll give you a piece of advice--Your mission is more sensitive than you think. The painter Ensor is a respected man in Belgium, and I mean by both the Walloons and the Flemish. Did you know that the king made a baron out of him before the war? My job is to keep the peace, to make certain that Belgian industry works at one hundred percent capacity in support of the German war effort!"

The general leaned back and stroked the head of the sleeping dachshund with two spidery fingers. Then he looked up, and the light caught his spectacles and made half-moon reflections on his sallow cheeks.

"So?"

"If you will allow me, sir," I said, "I'd like to try to explain the position of the corps in this matter."

He gave an assenting grunt.

I cleared my throat and paused a moment, trying to remember some of the exact words and phrases used in the propaganda manual.

"The Führer has called the Jews negative supermen," I began. "'Give me five hundred Jews,' he said, 'and I will take over Sweden in five years from the inside out. At the end of five years they will occupy every position of importance in the country--in industry, banking, and of course the arts.' Naturally there is no doubt as to the truth of the Führer's words, though if you ask me, sir, whether the takeover of Sweden would be accomplished through the cleverness of the Jews or the stupidity of the Swedes is a matter for conjecture. When we realize--"

The general interrupted with a quick chop of his hand. "Spare me the usual cant about the Jews, Graebner. Get to the point!"

"The point--"

"Wait." He interrupted again. "Tell me something. Why did they select you for this foolish duty? You're a soldier; what do you know about art?"

"I wasn't always a soldier, sir," I said. "Once I was an art student at the Prussian Academy of Arts and Architecture in Brandenburg. This was during the worst days of the Weimar corruption. Much of the art produced at the academy then was perverse, pro-Bolshevist, Jewish. Depictions of sexual acts, antiwar themes, portraits of cretins and dwarfs and so on. I left Brandenburg because the unwholesome un-German atmosphere made my head spin. In '33 I joined the party and became an art critic for Der Angriff, in which capacity I served until the commencement of hostilities. Then I enlisted in the corps and at my request was assigned to the armored division. After I was wounded, they reviewed my record and reassigned me to the Kulturkampf sector of the Polizeidivision."

"I see." The general nodded. "And how many other art critics do you suppose enlisted in the SS?" He asked this question in a very loud voice, and I heard a guffaw from someone in the adjoining room. I felt my ears going red.

"More than one might think, Herr General," I said, managing to keep my voice steady. "Perhaps because art is vital to the progress of National Socialism. The Führer himself has very often insisted on the political basis of all art. He has said that artistic anarchy is an incitement to political anarchy. Well, this is undoubtedly very true. Art is not merely a nice picture on a wall, a knickknack on a table. It is the very soul of the people. In shooting artists deemed degenerate by all common standards of decency, the Führer is showing conversely how important art and artists are to all of us."

When I finished this little speech, General von Falkenhausen drummed his fingertips on the dark wood of the desk and was silent. He removed his pince-nez spectacles again, rubbed the bridge of his nose, replaced them.

"You believe all that nonsense?" he said at last.

"I believe what I am told to believe, sir," I said.

"Let me see if I understand you," he said. "By shooting this Ensor fellow, you will be affirming his importance as an artist?"

"The work is unpleasant, I admit," I said. "I would rather be serving at the front with my old comrades, but in the interest of National Socialism--"

"Yes, yes!" The general stood out of his chair abruptly. The dachshund fell off his lap to the floor with a yelp. "If Himmler is determined to shoot another foolish artist, go ahead, shoot away, but I wash my hands of the whole affair! And I warn you, Ensor is different. Find some concrete excuse, produce evidence that he's been plotting against the Reich, that he's been making bombs in his basement, hiding spies. None of this vague talk about degenerate art! Fix this one carefully, or there will be hell to pay with the Belgians. Even a drop of one-half of one percent in the productivity of their armaments factories means German soldiers dead on the battlefield. Do you understand?"

General von Falkenhausen did not wait for my response. He went down on his hands and knees to retrieve both dachshunds from under the desk.

"Dismissed!" he called out from the shadowy recesses of this heavy piece of furniture. I struggled out of the chair, clicked the heels of my boots together, and limped out of the room and down the hall to the grand staircase.

Outside, along the strand, a winter dark was descending from

the east. The clouds had lifted off, and a sliver of moon hung over the sea, still vaguely phosphorescent as if the sun, sunk beneath

the waves, were now illuminating the ultimate depths. The men stood behind the steel shields of the antiaircraft guns, nervous, talking in low voices, dark shapes against the greater darkness, their eyes scanning the featureless horizon for the first sign of the enemy bombers, their ears straining for the first faint rumblings on the wind.

The Hôtel Kermesse, a gloomy little place on a quiet back street far from the beach, was the preferred stopping place for SS officers in Ostend. The thin walls of its small stuffy rooms were covered with peeling green wallpaper and garishly lit by amber cornucopia sconces that had been chic around 1920. At either end of the public area downstairs hung giant papier-mâché masks, relics of the pre-Lenten carnival, a bacchanal of public lewdness for which Ostend had become notorious in the years following the last war. From the hotel's narrow windows could be glimpsed the imposing edifice of the Belgian Thermal Institute for Hydropathic and Electrotherapy Treatment, a venerable medical establishment recently converted to less medical uses by the Gestapo.

A stoop-shouldered youth with a long, pimply face stepped up to me as I waited for the elevator. His greasy hair hung down across his eyes; encircling one sleeve of his mackintosh, the white and red armband of the VNV, the Flemish Fascist Party.

"Untersturmführer Graebner?"

I nodded, and the youth pulled himself up and delivered the full fascist salute. "Heil Hitler!"

"Heil Hitler," I said, "what do you want?"

"My name is Joop van Stijl, sir. I've been instructed by the local party chapter to act as your guide and interpreter." He showed me his orders, which had been routed through SS headquarters, Brussels. "Can I be of any assistance?"

I thought for a moment. "Do you know a decent restaurant that's not too far away? Presently I have some difficulty walking."

"German officers always eat in the dining room at the Hôtel Continental des Bains, sir," he said eagerly.

"So I understand," I said, "but tonight I prefer to dine elsewhere."

The youth scratched his greasy head. Out along the sidewalk a man in a long brown coat passed with the slow, jerky gait of a cripple, and I thought of myself. I didn't feel like enduring the snide comments of the Wehrmacht officers in the dining room at the continental as they stuffed their faces with Wiener schnitzel and carrots, I didn't feel like putting on a clean uniform, polishing my boots. Just then the long, low moan of the blackout sirens howled through the streets, and everywhere, in every house, there was a slow drawing down of blinds.

Sentimental French music played from the radio on the shelf above the bar. A dozen torpedo-shaped bottles of Dutch gin were set against a dusty mirror to the right of the ancient cash register of greening brass. A sad looking Flemish woman brought out bread, soft cheese, an iron crock of mussels steamed in white wine and garlic, a plate of fried potatoes, liter glasses of beer. The Belgian beer is sweet and heavy and very strong. I didn't realize how strong until I had downed a liter and a half and felt drunk. Despite the garlic, the mussels tasted of the sea.

"There will never be a shortage of mussels in Belgium," Joop said with his mouth full. "If we want mussels, all we have to do is go out at low tide. There they are, stuck to every rock. Of course in Germany I don't guess you have to worry about shortages!"