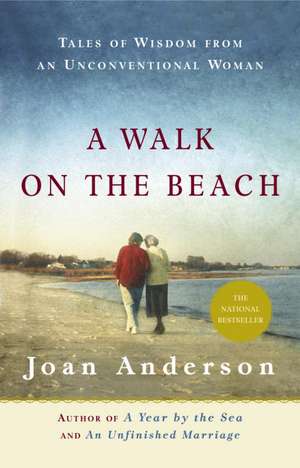

A Walk on the Beach: Tales of Wisdom from an Unconventional Woman

Autor Joan Andersonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2005

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Nautilus Award (2005)

Joan Erikson was perhaps best known for her collaboration with her husband, Erik, a pioneering psychoanalyst and noted author. After Erik’s death, she wrote several books extending their theory of the stages of life to reflect her understanding of aging as she neared ninety-five. But her wisdom was best taught through their friendship; as she sat with Anderson, weaving tapestries of their lives with brightly colored yarn while exploring the strength gathered from their accumulated experiences, Joan Erikson’s lessons took shape on their small cardboard looms as well as in her friend’s revitalized life.

In writing about their extraordinary friendship, Anderson reveals a need she didn’t know she had: for a mentor to help navigate the transitions she faced as she grew beyond middle age. And when Joan Erikson had to face her husband’s death and the growing limitations of her own body, Anderson was able to give back some of the wisdom she had gleaned. To this poignant, joyful account, Joan Anderson brings the candor and sensitivity that have made her an acclaimed speaker and writer on midlife and its possibilities. A Walk on the Beach is an experience to savor and treasure, a glimpse of the exuberant spirit that can be sustained and passed on in all our friendships.

Preț: 104.36 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.97€ • 20.77$ • 16.49£

19.97€ • 20.77$ • 16.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767914758

ISBN-10: 0767914759

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767914759

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

JOAN ANDERSON is the author of the bestsellers A Year by the Sea and An Unfinished Marriage. She has also written numerous children’s novels, including 1787, The First Thanksgiving Feast, and The American Family Farm, as well as a critically acclaimed adult nonfiction book Breaking the TV Habit (Scribner). A Walk on the Beach is her third work of narrative nonfiction. A graduate of Yale University School of Drama, Anderson lives with her husband on Cape Cod.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

OUT OF THE FOG

The call came as I was dressing to go out for dinner. "Joan's dying," her caretaker announced without preamble.

"What?" I was stunned and held the phone in silence as my heart began pumping. "How could that possibly be?" I asked, trying to push away the stark finality of Karen's statement. "She was perfectly fine just a week ago, and so full of herself at her birthday party." I could hear my voice pleading.

"I know," Karen continued, "but sometime last week she took to bed, her will broken somehow. These last few months have been such a struggle. She so detested the nursing home."

That was an understatement. Joan once told me that she thought putting an elder in a nursing home was a bit like taking the person to the dump. "The facilities are usually so far out of town," she said, "and the poor inmates are estranged from everything real about life." But as her fainting spells and frailty increased, her family and doctors felt that she needed the supervision, especially since she had a habit of firing the nurses hired to watch over her at home. Ever since she had been moved, though, I had watched her energy and determination slowly fade.

"Is she allowed visitors?" I asked.

"Yes, you could go over now, if you like. The family is having dinner."

I hung up the phone and sank into a nearby chair. A routine day had suddenly taken on immense implications. For the past several years Joan had been my mainstay. Although in many ways she appeared to be the antithesis of me-tall, patrician, at home in her body, overflowing with thought-provoking ideals-we quickly saw that we were both seekers. She was searching for ways to stay involved and vital until the end, and I, to depart from a structured life and all the roles I had been playing.

When Joan first appeared, I was in dire need of someone to help me jump-start my staid life, and she was the perfect coach. I had always gravitated to older people, especially those who distinguished themselves. Joan was wise, a bohemian by nature, who had routinely defied society's rules. Even more important, she made it clear that whatever we did together, we were going to have fun. Since she was full of surprises, I suppose I shouldn't have been shocked that she would depart from this world without warning. Still, to hear that her death was imminent was too much to grasp. I needed to get to her bedside and see for myself.

Stifling my tears, I grabbed my car keys and drove off, harboring the hope that Karen was simply being dramatic and that Joan would soon be returning to her puckish self. The fifteen-minute drive passed quickly as visions flooded my mind-Joan at the beach, plopping seaweed on top of her head to look like a mermaid; Joan dancing around my kitchen on a cold winter's evening to the Beatles' "Hard Day's Night"; Joan riding in the back of a pickup truck, holding on tight while we skidded through thick sand on the way to the tip of North Beach.

I pulled into Brewster Manor's parking lot and headed for the nurse's station. At her own home, Joan would greet me on her deck, waving with both arms extended in a grand gesture. But away from her beloved small-town sounds-clanging church bells, chirping birds, and neighborhood children at play-her enthusiasm for grand salutations had waned.

I made my way down the antiseptic hallway, dreary on most days but especially cheerless in the evening, and as I turned the corner, I saw a nurse exiting her room. "Is she . . ." I stumbled over my words, not wanting to suggest the worst.

"She's resting comfortably," the nurse assured me. "You may go in." I pried open the door and was greeted by a gentle breeze. Soft Celtic music played on a radio and the mesh curtains moved gently with the summer air. The walls were covered with pictures of friends, all of whom had only recently come to celebrate her ninety-fifth birthday. There was Joan, small frame tucked beneath crisp white sheets, her shrunken body so still, eyes welded shut. It was strange to see her so still. She had inspired me so-breathed life into me, as the Latin root says. How I yearned to be able to do that for her now.

I inched closer and sank down on the edge of the bed, not sure what to do next. "It's all in the touch," she used to say. "That's where you find the most in life." So I took hold of her paper-thin hand, gently rubbed her wrist and arm, and whispered, "I love you. Joanie, can you hear me? It's me. I'm here and I love you so very, very much." I paused after a few moments, hoping for some indication that she was aware of my presence-a wink, a nod, a squeezing of my hand would do, but nothing came. Nevertheless, as I gazed at the flickering candle on her bedside table, I couldn't help but smile, thinking back to our accidental meeting and realizing that from the beginning, her flame had lit the way.

It was a dank, eerie February afternoon. The white world left behind by last week's snowstorm had turned to gray mush as the Gulf Stream blew its warm breath over the land. Even my hearty shell path was washing away as the piles of snow turned to water. I had been marooned in my little summer cottage all week with too many empty hours to dwell on feeling sorry for myself. My father was dead, my mother was losing her mind, my husband had started a new job far away, my sons were grown and gone, and where was I? A woman adrift-with unhealed wounds to prove it-a body forsaken, most daily functions given over to others, and a will detoured. I had retreated to Cape Cod to find some answers. Alone, in a warm and forgiving setting, I was convinced that I could right myself. But months had gone by, and I was still at a crossroads. Did I want to stay married or not? Should I continue writing children's books or do something else? What was the meaning of my life? Was all this soul-searching simply an exercise in narcissism? The only clear thought I had was that I didn't want merely to age . . . I wanted to compile experiences, lots of them.

As I gazed out the window, I saw that the thaw had created a formless fog that obscured all but the closest landmarks, not unlike my unfocused life. I strained to hear some sound other than the dripping of icicles. Coming through behind the silence, I heard a foghorn. Its steady drone called me out of my torpor and into the outside world.

I donned a yellow slicker, hopped into the car, plowed through the slush, and followed the horn to the shore as if it were a mother calling me home. Once at the beach, I walked gingerly, barely able to see my hand in front of my face. The sound of the lapping surf beckoned me toward the water's edge and helped me get my bearings. Suddenly, I knew that my goal was the jetty, a huge arm of rocks that defined the harbor at the end of this beach.

In fifteen minutes or so, I scrambled up onto the mighty boulders and began stepping from one to the next, intent on going all the way out to the invisible tip. Utterly alone, I felt a wild abandon and realized that I was enjoying the solitariness of my adventure as much as anything else. But then I took a few more steps and found myself inches away from the chiseled profile of an old woman. She stood tall, a black cape flowing behind her, and looked out beyond the rocks almost as if she were a figurehead on the bow of a boat. It took me a minute or two to decide if she was real; then she turned her sparkling blue eyes on me. "Well, hello there. Are we the only ones in this town in a fog?" she quipped.

I chuckled at her play on words. "I hadn't thought of it that way. How do you do," I said, extending my hand. "I'm Joan Anderson."

"Really," she replied. "How curious. I'm Joan as well!"

I was still startled by her presence and momentarily at a loss for words.

"I just moved here," she continued, filling in the void. "Wonderful town, isn't it? I can't get enough of this beach."

"Where did you move from?"

"Cambridge," she said. "And you?"

"We have a summer cottage at the edge of town," I replied. "It's my first winter here."

"Are you living alone?" she asked.

"Yes." And then I surprised myself by continuing. "It's been quite a challenge being solo after a lifetime of living with a husband."

"Where is he?" she asked. I hadn't intended to spill out my story to a stranger, but my own honesty had prompted her question, so I attempted an answer.

"On Long Island. He took a new job and I decided not to go with him." I had never recounted that momentous decision quite so succinctly and was relieved to be met with a warm smile. As if sensing my embarrassment, she began to move.

"Would you care to join me?" she asked, even though I was already following her. Waves spilled over the tops of the rocks as we tiptoed around the slippery seaweed and puddles. Joan sped ahead with an agility that left me dumbfounded. How does she manage, I wondered. She must be eighty-five at least. "How come you're so nimble?" I asked out loud.

"Dance, my dear . . . it's been my passion forever."

"Do you still dance?"

"Whenever I get the chance," she said with a backward glance, as she extended one arm and pirouetted on her toes like a ballerina. Although I noticed that she grasped a gnarly cane, it seemed like a prop and simply added to her extraordinary gracefulness.

"What brought you out here on a afternoon like this?" I asked, my curiosity getting the best of me.

"Oh, I don't know. I suppose I was drawn to the grayness of the day," she said. "The mist sort of wraps around my thoughts and allows them to take hold. And you? What are you doing here?"

"Cabin fever," I replied somewhat more mundanely. "Last week's storm held me captive. My cottage is at the end of a very long road and there was no one to plow me out." Since she didn't respond to my explanation, I felt compelled to elaborate. "I feel a bit like that little boat smacking against the jetty," I continued, pointing one out a few feet away.

For a moment she stopped and let me catch up to her.

"How's that?" she asked.

"Oh, I don't know. I suppose I feel loosened, even free, now that I've eliminated all the responsibilities of my former life. But unfortunately, I also feel at sea, left without an oar or any idea of where I'm meant to row." Why was I babbling on-chatting so intimately to a virtual stranger?

"Funny you should describe your situation that way, dear, because I'm at sea as well," she admitted.

"You are?" I answered. "How so?"

"My husband isn't well," she said, all melody draining out of her voice. "I couldn't manage the two of us on my own any longer. Now that I'm here, we'll see what happens."

"Did you move him into a facility of some sort?"

"Oh, yes, a little nursing home in town," she said, pulling herself up and glaring out into the nothingness as if to defy a sense of resignation.

"How is it working?" I inquired cautiously.

"Nicely enough. A small town makes all the difference. But most importantly, I was able to buy a house just up the street," she said with a chuckle, utterly delighted with her accomplishment. "I detest being confined, especially in a place with schedules and rules."

I was impressed. How did someone her age manage to rearrange her life so well? I was barely coping and I had only myself to think about. Before I could ask another question, she turned and squinted as if she had caught sight of something off in the distance. "It's important to always look out, not back," she said in a faraway voice. "I've left lots of luggage onshore, hoping I'll find some new things out here."

"The fishermen think like that," I said. "They go out, day after day, trusting the voyage and casting their nets on a whim. They always seem to come up with something."

"I'm not surprised." She nodded. "As far as I'm concerned vital living is all about action and touch. That's where you find the wisdom-in what you're doing and feeling. Stepping out on a gray day, immersing oneself in the elements, daring to be different, that's the way to go. Thank goodness, there's no one as foolish as us right now. We can be in a fog all by ourselves!" And with that, she dropped her hood to let the air blow through her hair, increased her pace, and seemed intent on skipping the rest of the way.

"Sometimes I think women are like the fog."

"How do you mean?" she asked, stopping on a dime and turning toward me.

"We have a knowledge of what is underneath, but our real selves are obscured by what others think of us."

"Well, I suppose that's so. The mysterious female," she said with a hint of drama in her voice. "We'd best keep it that way."

I laughed at her gentle feminism. "I've been out here a hundred times and have never come across the likes of you." I stepped ahead and extended a hand to help her across the gaps in the rocks.

"It's all right, Mommy," she said, rejecting my help. "This old body hasn't failed me yet."

Eventually we arrived at the tip of the jetty and leaned against the base of the channel marker, yielding now to the wildness. As the bell clanged with the shifting wind, a gray-and-white gull swooped in and circled around us several times, flying so close we could see the intricate pattern of its feathers wrapped around its delicate cartilage. "What a beautiful creature," she exclaimed. "I bet it feels free, just like us right now."

"That's why I come here. It's a great place just to be and to think," I said, recalling the many times I'd sought out this place in the past couple of months, always leaving feeling uplifted somehow.

"There's more to life than thinking," she said gently, not meaning to contradict but wanting to make a point. "Everyone is soooo serious, don't you think?"

OUT OF THE FOG

The call came as I was dressing to go out for dinner. "Joan's dying," her caretaker announced without preamble.

"What?" I was stunned and held the phone in silence as my heart began pumping. "How could that possibly be?" I asked, trying to push away the stark finality of Karen's statement. "She was perfectly fine just a week ago, and so full of herself at her birthday party." I could hear my voice pleading.

"I know," Karen continued, "but sometime last week she took to bed, her will broken somehow. These last few months have been such a struggle. She so detested the nursing home."

That was an understatement. Joan once told me that she thought putting an elder in a nursing home was a bit like taking the person to the dump. "The facilities are usually so far out of town," she said, "and the poor inmates are estranged from everything real about life." But as her fainting spells and frailty increased, her family and doctors felt that she needed the supervision, especially since she had a habit of firing the nurses hired to watch over her at home. Ever since she had been moved, though, I had watched her energy and determination slowly fade.

"Is she allowed visitors?" I asked.

"Yes, you could go over now, if you like. The family is having dinner."

I hung up the phone and sank into a nearby chair. A routine day had suddenly taken on immense implications. For the past several years Joan had been my mainstay. Although in many ways she appeared to be the antithesis of me-tall, patrician, at home in her body, overflowing with thought-provoking ideals-we quickly saw that we were both seekers. She was searching for ways to stay involved and vital until the end, and I, to depart from a structured life and all the roles I had been playing.

When Joan first appeared, I was in dire need of someone to help me jump-start my staid life, and she was the perfect coach. I had always gravitated to older people, especially those who distinguished themselves. Joan was wise, a bohemian by nature, who had routinely defied society's rules. Even more important, she made it clear that whatever we did together, we were going to have fun. Since she was full of surprises, I suppose I shouldn't have been shocked that she would depart from this world without warning. Still, to hear that her death was imminent was too much to grasp. I needed to get to her bedside and see for myself.

Stifling my tears, I grabbed my car keys and drove off, harboring the hope that Karen was simply being dramatic and that Joan would soon be returning to her puckish self. The fifteen-minute drive passed quickly as visions flooded my mind-Joan at the beach, plopping seaweed on top of her head to look like a mermaid; Joan dancing around my kitchen on a cold winter's evening to the Beatles' "Hard Day's Night"; Joan riding in the back of a pickup truck, holding on tight while we skidded through thick sand on the way to the tip of North Beach.

I pulled into Brewster Manor's parking lot and headed for the nurse's station. At her own home, Joan would greet me on her deck, waving with both arms extended in a grand gesture. But away from her beloved small-town sounds-clanging church bells, chirping birds, and neighborhood children at play-her enthusiasm for grand salutations had waned.

I made my way down the antiseptic hallway, dreary on most days but especially cheerless in the evening, and as I turned the corner, I saw a nurse exiting her room. "Is she . . ." I stumbled over my words, not wanting to suggest the worst.

"She's resting comfortably," the nurse assured me. "You may go in." I pried open the door and was greeted by a gentle breeze. Soft Celtic music played on a radio and the mesh curtains moved gently with the summer air. The walls were covered with pictures of friends, all of whom had only recently come to celebrate her ninety-fifth birthday. There was Joan, small frame tucked beneath crisp white sheets, her shrunken body so still, eyes welded shut. It was strange to see her so still. She had inspired me so-breathed life into me, as the Latin root says. How I yearned to be able to do that for her now.

I inched closer and sank down on the edge of the bed, not sure what to do next. "It's all in the touch," she used to say. "That's where you find the most in life." So I took hold of her paper-thin hand, gently rubbed her wrist and arm, and whispered, "I love you. Joanie, can you hear me? It's me. I'm here and I love you so very, very much." I paused after a few moments, hoping for some indication that she was aware of my presence-a wink, a nod, a squeezing of my hand would do, but nothing came. Nevertheless, as I gazed at the flickering candle on her bedside table, I couldn't help but smile, thinking back to our accidental meeting and realizing that from the beginning, her flame had lit the way.

It was a dank, eerie February afternoon. The white world left behind by last week's snowstorm had turned to gray mush as the Gulf Stream blew its warm breath over the land. Even my hearty shell path was washing away as the piles of snow turned to water. I had been marooned in my little summer cottage all week with too many empty hours to dwell on feeling sorry for myself. My father was dead, my mother was losing her mind, my husband had started a new job far away, my sons were grown and gone, and where was I? A woman adrift-with unhealed wounds to prove it-a body forsaken, most daily functions given over to others, and a will detoured. I had retreated to Cape Cod to find some answers. Alone, in a warm and forgiving setting, I was convinced that I could right myself. But months had gone by, and I was still at a crossroads. Did I want to stay married or not? Should I continue writing children's books or do something else? What was the meaning of my life? Was all this soul-searching simply an exercise in narcissism? The only clear thought I had was that I didn't want merely to age . . . I wanted to compile experiences, lots of them.

As I gazed out the window, I saw that the thaw had created a formless fog that obscured all but the closest landmarks, not unlike my unfocused life. I strained to hear some sound other than the dripping of icicles. Coming through behind the silence, I heard a foghorn. Its steady drone called me out of my torpor and into the outside world.

I donned a yellow slicker, hopped into the car, plowed through the slush, and followed the horn to the shore as if it were a mother calling me home. Once at the beach, I walked gingerly, barely able to see my hand in front of my face. The sound of the lapping surf beckoned me toward the water's edge and helped me get my bearings. Suddenly, I knew that my goal was the jetty, a huge arm of rocks that defined the harbor at the end of this beach.

In fifteen minutes or so, I scrambled up onto the mighty boulders and began stepping from one to the next, intent on going all the way out to the invisible tip. Utterly alone, I felt a wild abandon and realized that I was enjoying the solitariness of my adventure as much as anything else. But then I took a few more steps and found myself inches away from the chiseled profile of an old woman. She stood tall, a black cape flowing behind her, and looked out beyond the rocks almost as if she were a figurehead on the bow of a boat. It took me a minute or two to decide if she was real; then she turned her sparkling blue eyes on me. "Well, hello there. Are we the only ones in this town in a fog?" she quipped.

I chuckled at her play on words. "I hadn't thought of it that way. How do you do," I said, extending my hand. "I'm Joan Anderson."

"Really," she replied. "How curious. I'm Joan as well!"

I was still startled by her presence and momentarily at a loss for words.

"I just moved here," she continued, filling in the void. "Wonderful town, isn't it? I can't get enough of this beach."

"Where did you move from?"

"Cambridge," she said. "And you?"

"We have a summer cottage at the edge of town," I replied. "It's my first winter here."

"Are you living alone?" she asked.

"Yes." And then I surprised myself by continuing. "It's been quite a challenge being solo after a lifetime of living with a husband."

"Where is he?" she asked. I hadn't intended to spill out my story to a stranger, but my own honesty had prompted her question, so I attempted an answer.

"On Long Island. He took a new job and I decided not to go with him." I had never recounted that momentous decision quite so succinctly and was relieved to be met with a warm smile. As if sensing my embarrassment, she began to move.

"Would you care to join me?" she asked, even though I was already following her. Waves spilled over the tops of the rocks as we tiptoed around the slippery seaweed and puddles. Joan sped ahead with an agility that left me dumbfounded. How does she manage, I wondered. She must be eighty-five at least. "How come you're so nimble?" I asked out loud.

"Dance, my dear . . . it's been my passion forever."

"Do you still dance?"

"Whenever I get the chance," she said with a backward glance, as she extended one arm and pirouetted on her toes like a ballerina. Although I noticed that she grasped a gnarly cane, it seemed like a prop and simply added to her extraordinary gracefulness.

"What brought you out here on a afternoon like this?" I asked, my curiosity getting the best of me.

"Oh, I don't know. I suppose I was drawn to the grayness of the day," she said. "The mist sort of wraps around my thoughts and allows them to take hold. And you? What are you doing here?"

"Cabin fever," I replied somewhat more mundanely. "Last week's storm held me captive. My cottage is at the end of a very long road and there was no one to plow me out." Since she didn't respond to my explanation, I felt compelled to elaborate. "I feel a bit like that little boat smacking against the jetty," I continued, pointing one out a few feet away.

For a moment she stopped and let me catch up to her.

"How's that?" she asked.

"Oh, I don't know. I suppose I feel loosened, even free, now that I've eliminated all the responsibilities of my former life. But unfortunately, I also feel at sea, left without an oar or any idea of where I'm meant to row." Why was I babbling on-chatting so intimately to a virtual stranger?

"Funny you should describe your situation that way, dear, because I'm at sea as well," she admitted.

"You are?" I answered. "How so?"

"My husband isn't well," she said, all melody draining out of her voice. "I couldn't manage the two of us on my own any longer. Now that I'm here, we'll see what happens."

"Did you move him into a facility of some sort?"

"Oh, yes, a little nursing home in town," she said, pulling herself up and glaring out into the nothingness as if to defy a sense of resignation.

"How is it working?" I inquired cautiously.

"Nicely enough. A small town makes all the difference. But most importantly, I was able to buy a house just up the street," she said with a chuckle, utterly delighted with her accomplishment. "I detest being confined, especially in a place with schedules and rules."

I was impressed. How did someone her age manage to rearrange her life so well? I was barely coping and I had only myself to think about. Before I could ask another question, she turned and squinted as if she had caught sight of something off in the distance. "It's important to always look out, not back," she said in a faraway voice. "I've left lots of luggage onshore, hoping I'll find some new things out here."

"The fishermen think like that," I said. "They go out, day after day, trusting the voyage and casting their nets on a whim. They always seem to come up with something."

"I'm not surprised." She nodded. "As far as I'm concerned vital living is all about action and touch. That's where you find the wisdom-in what you're doing and feeling. Stepping out on a gray day, immersing oneself in the elements, daring to be different, that's the way to go. Thank goodness, there's no one as foolish as us right now. We can be in a fog all by ourselves!" And with that, she dropped her hood to let the air blow through her hair, increased her pace, and seemed intent on skipping the rest of the way.

"Sometimes I think women are like the fog."

"How do you mean?" she asked, stopping on a dime and turning toward me.

"We have a knowledge of what is underneath, but our real selves are obscured by what others think of us."

"Well, I suppose that's so. The mysterious female," she said with a hint of drama in her voice. "We'd best keep it that way."

I laughed at her gentle feminism. "I've been out here a hundred times and have never come across the likes of you." I stepped ahead and extended a hand to help her across the gaps in the rocks.

"It's all right, Mommy," she said, rejecting my help. "This old body hasn't failed me yet."

Eventually we arrived at the tip of the jetty and leaned against the base of the channel marker, yielding now to the wildness. As the bell clanged with the shifting wind, a gray-and-white gull swooped in and circled around us several times, flying so close we could see the intricate pattern of its feathers wrapped around its delicate cartilage. "What a beautiful creature," she exclaimed. "I bet it feels free, just like us right now."

"That's why I come here. It's a great place just to be and to think," I said, recalling the many times I'd sought out this place in the past couple of months, always leaving feeling uplifted somehow.

"There's more to life than thinking," she said gently, not meaning to contradict but wanting to make a point. "Everyone is soooo serious, don't you think?"

Descriere

"In "A Year by the Sea" and "An Unfinished Marriage," Anderson shared her account of taking a break from her marriage and spending a year of solitude at the beach. Now, she introduces the inspiring woman she befriended during that time: Joan Erikson, wife of psychoanalyst Erik Erikson."--"Publishers Weekly."

Premii

- Nautilus Award Finalist, 2005