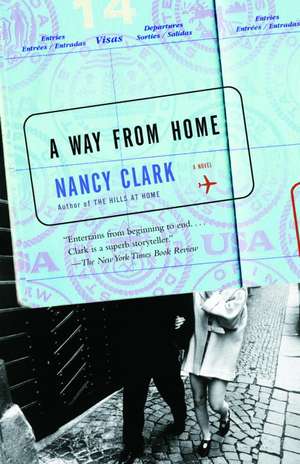

A Way from Home

Autor Nancy Clarken Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2006

In its tale of Americans living abroad and the social reconfigurations that ensue, the captivating A Way from Home is reminiscent of the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James--with a delicious satiric tang all its own.

Preț: 83.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 125

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.94€ • 16.68$ • 13.19£

15.94€ • 16.68$ • 13.19£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400078714

ISBN-10: 1400078717

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400078717

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 134 x 207 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Nancy Clark lives in West Wilton, New Hampshire, where she is at work on her third novel, July and August.

Extras

“Becky? Where are you? Well, don’t move. Just stay where you are or we’ll lose one another,” Alden called out.

But Becky, wherever she had settled with an English magazine or her tapestry frame or the briefcase full of paperwork she had brought home for the weekend, would never hear him through the thick stone walls of the some-centuries-old castle in which they had been living for the past two years. Alden spoke aloud to keep his spirits up, or, as he scarcely admitted to himself, to keep the spirits at bay as he paced the Great Hall through the darkness the wan beam thrown by his flash- light only cleaved into blacker halves. So halved, the deepened gloom pressed twice as tenebrous on the left and on the right as Alden formed a sort of certainty that whatever lurked in the murk to his left lowered even more banefully than the second secret horror eeling through the utter inkiness to his right.

He really hadn’t much good to say for Czech electricity. These power cuts happened too frequently and too mysteriously on perfect summer evenings when the air was so stilly composed that the ruffle-edged moths could not catch and heave themselves aloft on the least breath of air. This summer of 1992 in Prague was running so dry that the dependent wings of the wandering moths scritched across the parched earth and pavement. Alden had heard them as he lay upon his deck chair out in the lightless belvedere and slowly determined what the so-quiet creep and onward scrabble must be, aided by the brief flare and flame of a new and antique Cartier, or Cartier-style, lighter. He was sorry to say he had taken up smoking again. Tobacco was freely offered and enjoyed in this city and in this culture, although not within the culture and the keep of Castle Fortune, and so he smoked his Silk Cuts outside on a belvedere chaise as a conflux of grounded moths crept past him heading straight, he didn’t doubt, for the dressing room wardrobe and his camel-hair blazer’s slim and tender lapels.

“Rats.” Svatopluk, Alden’s right-hand man down at the Ministry of Finances outpost office, had offered this explanation for the power failures after Alden complained he had been prevented from toasting a too-hard bagel the night before. He had been given a globe-shaped jar of spreading honey by a supplicant speculator which may or may not have been intended as a bribe. If so, Alden was touched but not in the least suborned by the delicacy of the gesture. It was basswood honey, the supplicant said, which was said to taste of mint, but Alden, assessing a flavor conveyed by a sticky fingertip, privately thought, Bitter.

“Rats?” Alden had asked. “Do you mean those wretched rats you people keep running round inside revolving drums down at the generating station have all keeled over from fatal heart attacks?”

“Sir? No, no sir, no. Ha-ha, sir. I refer to the rodents gnawing on the cable wires, which taste of salt because of a galvanizing technique once in vogue. It is a problem. In fact, it is a scandal. No, our generators are, for the most part, coal powered,” Alden had been patiently reminded by Svatopluk, to whom the task too often fell of reminding Mr. Lowe patiently or tactfully or preventively.

Ah yes, thought Alden, they burn that spongy, crumbling, pallid Bohemian coal they can’t give away to the rest of the world free with magic beans, for he knew all about the fledgling Republic’s production deficiencies and trade imbalances. Few in Prague knew, or needed to know, better than he about such matters. Alden had hardly had to invent the notion of rodent dynamos on his own. He wasn’t sure he hadn’t come across their like in some wretchedly reproduced précis of yet another hopeful, pleading prospectus.

And as for Svatopluk, what sort of a name was Svatopluk? Alden wondered. Was it the equivalent of having an assistant named Jethro or Clem, or Julian or Byron, or Bill or Bob? Ought he to speak of Svatopluk naturally or with a voice freighted with irony? Was a Svatopluk, in the language of the Ministry, to be listed among one’s assets?

Furthermore, Alden minded these spontaneous blackouts because they caused him to misstep, as he misstepped now, off the edge of the thick-as-curbstone carpet laid down the span of the Long Gallery. He lurched and cracked himself against great carved objects. Very superior cupboards, Becky said they were, whose very superior contents had long since vanished along with the last Family in residence; to Paris and to Toronto, the Field Marshal and the porcelain had gotten away. Alden reminded himself that these obstacles could not possibly have been shoved out of position during the day to sabotage his blind progress. An army would have to be summoned to shift the towering chests and to lift the vast rugs. Any coin lost once and found now beneath the taken-up carpet would bear the image of one Habsburg or another turned to display a nonpareil profile to the least possessor of the merest haler. No, Alden’s sense of displacement was existential.

He hoped Svatopluk wasn’t Czech for Marmaduke.

Besides, Alden ventured less frequently into this part of the castle, crossing the Long Gallery toward the doors to the Pastels Room and the Music Chamber and the Southerly Conservatory, which constituted Becky’s particular apartment. We must live in a castle as a castle is meant to be lived in, Becky had grandly pronounced at the start. They had all played at being grand in those early days. Becky was the Comtesse and Alden her Comte, and even Julie had consented to answer to Milady with fairly good grace since her folks had been so obliging about calling her Julie—when they weren’t calling her Milady. Becky, after a considering stroll through their new domain while consulting an ancient floor plan printed on the heavy sheet of paper that the leasing agent had folded around the castle’s several dozen tremendous and unmarked keys suspended from a chain, had assigned Alden the Great Hall and the Armaments Chamber and the library as his private suite of rooms. All the chilly, antlered places were to be his portion. Male and female, she created them, as Alden had tolerantly thought at the time but did not, of course, speak aloud. Julie, as maiden, was sent uncomplainingly to the Tower, where she could play her stereo as loudly as she had ever wished to until she annoyed even herself.

Becky had been so vital reinventing their world for them those early amazing weeks in Prague, when they had all been unfailingly charmed by every aspect of the My Bookhouse scenery on offer and by the magnificent accommodations and by the welcoming locals who were delighted in turn to greet such exotic yet reassuringly true-to-type Americans. Alden and Becky and Julie smiled with such beautiful teeth and took such long, confident strides with their long, confident legs. They glowed; their healthy skin, their cared-for hair, their precious metal watch faces and rings caught the sunlight and captured the eye. Every occasion, every new face, every attempt at conversation, seemed to call for generous outpourings of Alden’s Scotch or an ice-cold Coca-Cola. The man who came to prod and prove the castle’s several mysterious boilers became cordially drunk and had to return with his several supervisors and their several apprentices on another day. The Lowes had had no problem summoning workmen to puzzle over, on successive visits, the kitchen stove that shuddered and sparked but would not light; the pull-chain apparatus, which was meant to open and close a glass panel in the conservatory roof but had come crashing down when tugged; and the drains of every bathtub in every bathroom that, when the plugs were raised, caused the level of water standing in the tub to rise as a swampish and sedimented liquid swirled upward from the waste pipes. Even though they were raw newcomers to such a foreign land, the Lowes were quite sure this was not correct. These were not the antipodes, where the drains twirled wrong way round, and nowhere on earth did water flow upward.

But the Lowes had stood on their heads in order not to come across as conquerors, for they felt like conquerors, and how could they not be perceived as conquerors in Prague in the autumn of 1990? They handed round filled glasses as if to old friends as they presided with those wide-open smiles well fixed to the faces, and they listened to the elaborate explanations of why repairs could not easily or ever entirely successfully be effected. Alden and Becky nodded along, not really comprehending but coming to recognize the tone, or the tune, the strains of Czech bel can’t -o, as Alden allowed. Technicians never said, You’re all set, as they did in the States, those three little words that made his heart sing. Becky had failed to smile (her smiles favored other people, these days) at Alden’s little joke. Besides, her bathtub now drained if a lever was jiggled, and her conservatory window could be pushed open and nudged shut by a telescoping pole and hook contraption, and the spark-spitting oven had been superseded by a gleaming La Cornue work of highly functional kitchen art that Alden was not allowed to use. He clattered and spattered the surfaces on the cook’s day off, Becky said, and she had chosen the snow-white model, which particularly showed spills.

Alden had had no clue back then in the early days that Becky had begun as she meant to go on. Her pronouncements and crotchets, to which he had at first lightheartedly ascribed, as if to the evolving outlines of some new, diverting game being played out between them, had become, over time, codified into the strictures of a regime. The game had engaged him; the regime had removed, in turn, the die, the tiles, the recent run of aces from his hand. The particular moment when he ought to have spoken up had passed, recognized only too late among the shapes and shadows inhabiting the becloudments of subsequent developments. Alden believed President Havel, back when he was Provocateur and sometimes Prisoner Havel, had explained in a seminal essay how this sort of darkness could fall over an unvigilant people, how they allowed such a thing to happen to themselves, indeed, how they were enlisted to facilitate their oppressors in the act of their own suppression. This was the best established method, known to be so in the very bones of all the hard-line bosses of old. Perhaps Becky had been infected by the germ of the idea, which survived as a mutating virus being breathed in and out on the not very clean air of the frail and infant Republic they had been sent to nurture. Alden guessed Becky would recover presently, and he would reassure her then that he had understood what she was going through. But now was not the moment to remind Becky that he knew her better than she knew herself. She might become strongly motivated to surprise him, and at this point in their long marriage, he reckoned, all the good surprises had been sprung. Heights of passion, delights in children—those sorts of surprises, Alden wagered, were over.

Thus, Alden spent most of his evenings at home alone in the library chamber. He sat at a long central table. His legs pressed against one or another of the table’s dozen legs, each table leg carved in the shape of the limbs of some manner of legendary beast, bescaled and hooved and muscular and woolly, the very beast which, for all Alden knew, had roamed Central Europe back in the days when England contained dragons and Ireland still had its snakes. Alden’s inner imagination was not well stocked with Central European mythic images. Last Christmas, the Prague street-corner Santa Clauses had struck him as clerical and stern-looking beings, and Alden had asked Svatopluk not just to explain the attenuated Father Christmases with their wispy beards and poignantly underfilled sacks but also to direct him to some primary source that would enlighten him and generally illuminate the native scene. Svatopluk had considered, and then consulted a known authority at Charles University who produced a fusty English translation of an allegorical work by a seventeenth-century local divine, The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, by one Johan Comenius. Exactly, Alden had said to himself, as he studied the title. He instantly accepted its premise: the world was a place of twists and turns, and of blocked and falling-open passageways, and, more often than not, of finding oneself back at the beginning, retracing one’s first too tentative or too trusting steps—whereas the human heart remained the secret, centered chamber where life and love were lodged and whose attendant sensations a seventeenth century might very well call paradisaical and which modern man would less extravagantly characterize but be no less thankful for. And reading further, pen in hand, Alden underlined and asterisked passages that struck him as sounding wise and true down to this very day.

He had set his long library table with a sequence of workstations. Feeling Mad Hatterish most evenings, he progressed from chair to massive chair, first to read his papers, next relocating to write up his notes, shifting himself to tap on his keyboard, and moving on then to telephone, after which he got up and sat down again to fax contracts to the as-yet-wide-awake West. He returned to his reading chair to study documents faxed to him in reply or in query. His days never quite seemed to end. They blurred one into the next, from the drifting-off West to the arising East, for he was casting his net wide on the fledgling Republic’s behalf to entice investors into taking a chance on a hundred dozen nascent privatization schemes. The Czechs had long manufactured very good steel and glass. Their small appliances enjoyed a fair reputation in the Third World. They produced cement and textiles and chemicals and potatoes and beets. In 1938, Czechoslovakia had boasted the fifteenth-best economy in the world. It had been, once upon a time, really a rather nice little country.

But Becky, wherever she had settled with an English magazine or her tapestry frame or the briefcase full of paperwork she had brought home for the weekend, would never hear him through the thick stone walls of the some-centuries-old castle in which they had been living for the past two years. Alden spoke aloud to keep his spirits up, or, as he scarcely admitted to himself, to keep the spirits at bay as he paced the Great Hall through the darkness the wan beam thrown by his flash- light only cleaved into blacker halves. So halved, the deepened gloom pressed twice as tenebrous on the left and on the right as Alden formed a sort of certainty that whatever lurked in the murk to his left lowered even more banefully than the second secret horror eeling through the utter inkiness to his right.

He really hadn’t much good to say for Czech electricity. These power cuts happened too frequently and too mysteriously on perfect summer evenings when the air was so stilly composed that the ruffle-edged moths could not catch and heave themselves aloft on the least breath of air. This summer of 1992 in Prague was running so dry that the dependent wings of the wandering moths scritched across the parched earth and pavement. Alden had heard them as he lay upon his deck chair out in the lightless belvedere and slowly determined what the so-quiet creep and onward scrabble must be, aided by the brief flare and flame of a new and antique Cartier, or Cartier-style, lighter. He was sorry to say he had taken up smoking again. Tobacco was freely offered and enjoyed in this city and in this culture, although not within the culture and the keep of Castle Fortune, and so he smoked his Silk Cuts outside on a belvedere chaise as a conflux of grounded moths crept past him heading straight, he didn’t doubt, for the dressing room wardrobe and his camel-hair blazer’s slim and tender lapels.

“Rats.” Svatopluk, Alden’s right-hand man down at the Ministry of Finances outpost office, had offered this explanation for the power failures after Alden complained he had been prevented from toasting a too-hard bagel the night before. He had been given a globe-shaped jar of spreading honey by a supplicant speculator which may or may not have been intended as a bribe. If so, Alden was touched but not in the least suborned by the delicacy of the gesture. It was basswood honey, the supplicant said, which was said to taste of mint, but Alden, assessing a flavor conveyed by a sticky fingertip, privately thought, Bitter.

“Rats?” Alden had asked. “Do you mean those wretched rats you people keep running round inside revolving drums down at the generating station have all keeled over from fatal heart attacks?”

“Sir? No, no sir, no. Ha-ha, sir. I refer to the rodents gnawing on the cable wires, which taste of salt because of a galvanizing technique once in vogue. It is a problem. In fact, it is a scandal. No, our generators are, for the most part, coal powered,” Alden had been patiently reminded by Svatopluk, to whom the task too often fell of reminding Mr. Lowe patiently or tactfully or preventively.

Ah yes, thought Alden, they burn that spongy, crumbling, pallid Bohemian coal they can’t give away to the rest of the world free with magic beans, for he knew all about the fledgling Republic’s production deficiencies and trade imbalances. Few in Prague knew, or needed to know, better than he about such matters. Alden had hardly had to invent the notion of rodent dynamos on his own. He wasn’t sure he hadn’t come across their like in some wretchedly reproduced précis of yet another hopeful, pleading prospectus.

And as for Svatopluk, what sort of a name was Svatopluk? Alden wondered. Was it the equivalent of having an assistant named Jethro or Clem, or Julian or Byron, or Bill or Bob? Ought he to speak of Svatopluk naturally or with a voice freighted with irony? Was a Svatopluk, in the language of the Ministry, to be listed among one’s assets?

Furthermore, Alden minded these spontaneous blackouts because they caused him to misstep, as he misstepped now, off the edge of the thick-as-curbstone carpet laid down the span of the Long Gallery. He lurched and cracked himself against great carved objects. Very superior cupboards, Becky said they were, whose very superior contents had long since vanished along with the last Family in residence; to Paris and to Toronto, the Field Marshal and the porcelain had gotten away. Alden reminded himself that these obstacles could not possibly have been shoved out of position during the day to sabotage his blind progress. An army would have to be summoned to shift the towering chests and to lift the vast rugs. Any coin lost once and found now beneath the taken-up carpet would bear the image of one Habsburg or another turned to display a nonpareil profile to the least possessor of the merest haler. No, Alden’s sense of displacement was existential.

He hoped Svatopluk wasn’t Czech for Marmaduke.

Besides, Alden ventured less frequently into this part of the castle, crossing the Long Gallery toward the doors to the Pastels Room and the Music Chamber and the Southerly Conservatory, which constituted Becky’s particular apartment. We must live in a castle as a castle is meant to be lived in, Becky had grandly pronounced at the start. They had all played at being grand in those early days. Becky was the Comtesse and Alden her Comte, and even Julie had consented to answer to Milady with fairly good grace since her folks had been so obliging about calling her Julie—when they weren’t calling her Milady. Becky, after a considering stroll through their new domain while consulting an ancient floor plan printed on the heavy sheet of paper that the leasing agent had folded around the castle’s several dozen tremendous and unmarked keys suspended from a chain, had assigned Alden the Great Hall and the Armaments Chamber and the library as his private suite of rooms. All the chilly, antlered places were to be his portion. Male and female, she created them, as Alden had tolerantly thought at the time but did not, of course, speak aloud. Julie, as maiden, was sent uncomplainingly to the Tower, where she could play her stereo as loudly as she had ever wished to until she annoyed even herself.

Becky had been so vital reinventing their world for them those early amazing weeks in Prague, when they had all been unfailingly charmed by every aspect of the My Bookhouse scenery on offer and by the magnificent accommodations and by the welcoming locals who were delighted in turn to greet such exotic yet reassuringly true-to-type Americans. Alden and Becky and Julie smiled with such beautiful teeth and took such long, confident strides with their long, confident legs. They glowed; their healthy skin, their cared-for hair, their precious metal watch faces and rings caught the sunlight and captured the eye. Every occasion, every new face, every attempt at conversation, seemed to call for generous outpourings of Alden’s Scotch or an ice-cold Coca-Cola. The man who came to prod and prove the castle’s several mysterious boilers became cordially drunk and had to return with his several supervisors and their several apprentices on another day. The Lowes had had no problem summoning workmen to puzzle over, on successive visits, the kitchen stove that shuddered and sparked but would not light; the pull-chain apparatus, which was meant to open and close a glass panel in the conservatory roof but had come crashing down when tugged; and the drains of every bathtub in every bathroom that, when the plugs were raised, caused the level of water standing in the tub to rise as a swampish and sedimented liquid swirled upward from the waste pipes. Even though they were raw newcomers to such a foreign land, the Lowes were quite sure this was not correct. These were not the antipodes, where the drains twirled wrong way round, and nowhere on earth did water flow upward.

But the Lowes had stood on their heads in order not to come across as conquerors, for they felt like conquerors, and how could they not be perceived as conquerors in Prague in the autumn of 1990? They handed round filled glasses as if to old friends as they presided with those wide-open smiles well fixed to the faces, and they listened to the elaborate explanations of why repairs could not easily or ever entirely successfully be effected. Alden and Becky nodded along, not really comprehending but coming to recognize the tone, or the tune, the strains of Czech bel can’t -o, as Alden allowed. Technicians never said, You’re all set, as they did in the States, those three little words that made his heart sing. Becky had failed to smile (her smiles favored other people, these days) at Alden’s little joke. Besides, her bathtub now drained if a lever was jiggled, and her conservatory window could be pushed open and nudged shut by a telescoping pole and hook contraption, and the spark-spitting oven had been superseded by a gleaming La Cornue work of highly functional kitchen art that Alden was not allowed to use. He clattered and spattered the surfaces on the cook’s day off, Becky said, and she had chosen the snow-white model, which particularly showed spills.

Alden had had no clue back then in the early days that Becky had begun as she meant to go on. Her pronouncements and crotchets, to which he had at first lightheartedly ascribed, as if to the evolving outlines of some new, diverting game being played out between them, had become, over time, codified into the strictures of a regime. The game had engaged him; the regime had removed, in turn, the die, the tiles, the recent run of aces from his hand. The particular moment when he ought to have spoken up had passed, recognized only too late among the shapes and shadows inhabiting the becloudments of subsequent developments. Alden believed President Havel, back when he was Provocateur and sometimes Prisoner Havel, had explained in a seminal essay how this sort of darkness could fall over an unvigilant people, how they allowed such a thing to happen to themselves, indeed, how they were enlisted to facilitate their oppressors in the act of their own suppression. This was the best established method, known to be so in the very bones of all the hard-line bosses of old. Perhaps Becky had been infected by the germ of the idea, which survived as a mutating virus being breathed in and out on the not very clean air of the frail and infant Republic they had been sent to nurture. Alden guessed Becky would recover presently, and he would reassure her then that he had understood what she was going through. But now was not the moment to remind Becky that he knew her better than she knew herself. She might become strongly motivated to surprise him, and at this point in their long marriage, he reckoned, all the good surprises had been sprung. Heights of passion, delights in children—those sorts of surprises, Alden wagered, were over.

Thus, Alden spent most of his evenings at home alone in the library chamber. He sat at a long central table. His legs pressed against one or another of the table’s dozen legs, each table leg carved in the shape of the limbs of some manner of legendary beast, bescaled and hooved and muscular and woolly, the very beast which, for all Alden knew, had roamed Central Europe back in the days when England contained dragons and Ireland still had its snakes. Alden’s inner imagination was not well stocked with Central European mythic images. Last Christmas, the Prague street-corner Santa Clauses had struck him as clerical and stern-looking beings, and Alden had asked Svatopluk not just to explain the attenuated Father Christmases with their wispy beards and poignantly underfilled sacks but also to direct him to some primary source that would enlighten him and generally illuminate the native scene. Svatopluk had considered, and then consulted a known authority at Charles University who produced a fusty English translation of an allegorical work by a seventeenth-century local divine, The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, by one Johan Comenius. Exactly, Alden had said to himself, as he studied the title. He instantly accepted its premise: the world was a place of twists and turns, and of blocked and falling-open passageways, and, more often than not, of finding oneself back at the beginning, retracing one’s first too tentative or too trusting steps—whereas the human heart remained the secret, centered chamber where life and love were lodged and whose attendant sensations a seventeenth century might very well call paradisaical and which modern man would less extravagantly characterize but be no less thankful for. And reading further, pen in hand, Alden underlined and asterisked passages that struck him as sounding wise and true down to this very day.

He had set his long library table with a sequence of workstations. Feeling Mad Hatterish most evenings, he progressed from chair to massive chair, first to read his papers, next relocating to write up his notes, shifting himself to tap on his keyboard, and moving on then to telephone, after which he got up and sat down again to fax contracts to the as-yet-wide-awake West. He returned to his reading chair to study documents faxed to him in reply or in query. His days never quite seemed to end. They blurred one into the next, from the drifting-off West to the arising East, for he was casting his net wide on the fledgling Republic’s behalf to entice investors into taking a chance on a hundred dozen nascent privatization schemes. The Czechs had long manufactured very good steel and glass. Their small appliances enjoyed a fair reputation in the Third World. They produced cement and textiles and chemicals and potatoes and beets. In 1938, Czechoslovakia had boasted the fifteenth-best economy in the world. It had been, once upon a time, really a rather nice little country.

Recenzii

"Entertains from beginning to end. . . . Clark is a superb storyteller" —The New York Times Book Review

“Brilliant, from the weekend idyll when a young Becky and William first fall in love to William's Libyan retreat ” —The Boston Globe

"Diamond-sharp social observations inspirit a literary romance. . . . Erudite evocations of time, people and place, all delivered in a dry, old-world voice." —Kirkus Reviews

“With great good humor and empathy, Nancy Clark creates a remarkable group of characters and conveys their real longing for home with all of its multiple meanings. . . . An exuberant romp.”—Roanoke Times

“Once again Clark demonstrates her consummate talent for yeasty prose that rises to every occasion . . . loaded with original takes on universal human experiences.” —Bookpage

“Brilliant, from the weekend idyll when a young Becky and William first fall in love to William's Libyan retreat ” —The Boston Globe

"Diamond-sharp social observations inspirit a literary romance. . . . Erudite evocations of time, people and place, all delivered in a dry, old-world voice." —Kirkus Reviews

“With great good humor and empathy, Nancy Clark creates a remarkable group of characters and conveys their real longing for home with all of its multiple meanings. . . . An exuberant romp.”—Roanoke Times

“Once again Clark demonstrates her consummate talent for yeasty prose that rises to every occasion . . . loaded with original takes on universal human experiences.” —Bookpage