Abayudaya: The Jews of Uganda

Autor Richard Sobol, Jeffrey A. Summiten Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 iul 2002

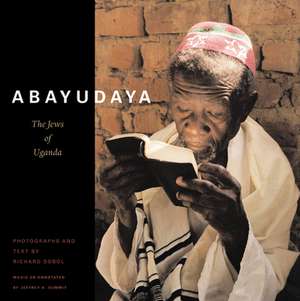

Told with captivating images and haunting music, here is the remarkable story of a group of rural African people who converted to Judaism eighty years ago and, despite ensuing hardships, have stuck by their faith. Abayudaya features 100 full–color photographs and a CD filled with powerful music and songs.

The 600 members of the Abayudaya (Children of Judah) community living in a remote area of eastern Uganda lead a life devoted to traditional Jewish practices. They observe the Sabbath and holidays, attend services, follow dietary laws, and cling tightly to traditions in their small mud and brick synagogues. Surrounded by Muslims and Christians, facing poverty and isolation, these people have maintained their Jewish way of life for four generations since the initial conversion of their tribal chief Semei Kukungulu in 1917. Even during Idi Amin's reign of terror, when synagogues were closed and prayers had to be held in secret, the Abayudaya did not abandon their beliefs.

Richard Sobol is the first photojournalist to document this newly discovered Jewish community's way of life and to relate their heroic story. His sensitive portraits and moving landscapes depict everyday life. He shows their day of rest on the Jewish Sabbath, as well as their religious celebrations and rituals. His intriguing text chronicles the story of this community from its conception to the present. The book includes a CD filled with powerful music and songs from services recorded by ethnomusicologist Jeffrey A. Summit, who has also provided an essay examining this unique mix of African and Jewish sounds.

The 600 members of the Abayudaya (Children of Judah) community living in a remote area of eastern Uganda lead a life devoted to traditional Jewish practices. They observe the Sabbath and holidays, attend services, follow dietary laws, and cling tightly to traditions in their small mud and brick synagogues. Surrounded by Muslims and Christians, facing poverty and isolation, these people have maintained their Jewish way of life for four generations since the initial conversion of their tribal chief Semei Kukungulu in 1917. Even during Idi Amin's reign of terror, when synagogues were closed and prayers had to be held in secret, the Abayudaya did not abandon their beliefs.

Richard Sobol is the first photojournalist to document this newly discovered Jewish community's way of life and to relate their heroic story. His sensitive portraits and moving landscapes depict everyday life. He shows their day of rest on the Jewish Sabbath, as well as their religious celebrations and rituals. His intriguing text chronicles the story of this community from its conception to the present. The book includes a CD filled with powerful music and songs from services recorded by ethnomusicologist Jeffrey A. Summit, who has also provided an essay examining this unique mix of African and Jewish sounds.

Preț: 340.38 lei

Preț vechi: 369.98 lei

-8% Nou

Puncte Express: 511

Preț estimativ în valută:

65.13€ • 68.17$ • 54.21£

65.13€ • 68.17$ • 54.21£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789207760

ISBN-10: 0789207761

Pagini: 168

Dimensiuni: 251 x 251 x 26 mm

Greutate: 1.24 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 0789207761

Pagini: 168

Dimensiuni: 251 x 251 x 26 mm

Greutate: 1.24 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Cuprins

Table of Contents from: Abayudaya

Foreword

Uganda's Jewish Community by Richard Sobol

Music and Songs from Services by Jeffrey A. Summit

Abayudaya Images

Index

MUSIC CD BOUND IN BACK ENDPAPERS

Foreword

Uganda's Jewish Community by Richard Sobol

Music and Songs from Services by Jeffrey A. Summit

Abayudaya Images

Index

MUSIC CD BOUND IN BACK ENDPAPERS

Recenzii

Praise for Abayudaya:

"Richard Sobol has a unique story to tell—the story of Abayudaya—a community of Bantu Jews from a remote region of Uganda. I have seen the photographs and was deeply moved by the work that he has created." — Elie Wiesel, winner of the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize

"A fascinating study of one of the world's most exotic Jewish communities in the fullness of their humanity and authenticity." — Rabbi Harold S. Kushner, author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People

"A beautiful coffee-table book…" — The Jewish Press

"Richard Sobol has a unique story to tell—the story of Abayudaya—a community of Bantu Jews from a remote region of Uganda. I have seen the photographs and was deeply moved by the work that he has created." — Elie Wiesel, winner of the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize

"A fascinating study of one of the world's most exotic Jewish communities in the fullness of their humanity and authenticity." — Rabbi Harold S. Kushner, author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People

"A beautiful coffee-table book…" — The Jewish Press

Notă biografică

Richard Sobol has contributed photoessays to such leading publications as National Geographic, Time, Newsweek, and The New York Times Magazine. He lives in Lexington, Massachusetts.

Rabbi Jeffrey A. Summit is the Neubauer Executive Director of Tufts Hillel at Tufts University, where he also teaches Music and Judaic Studies.

Rabbi Jeffrey A. Summit is the Neubauer Executive Director of Tufts Hillel at Tufts University, where he also teaches Music and Judaic Studies.

Extras

Excerpt from Abayudaya

The Hidden Tribe: The Story of the Jews of Uganda

In August 1999 a graduate student in anthropology at Boston University gave me a recording of Hebrew prayers chanted by the Abayudaya, a community of Bantu Jews from a remote region of Uganda. The melodies were a haunting blend of traditional Hebrew songs and rich African harmonies. I play this recording again and again, puzzling over its origins. How could this group of African Jews come to be? And how could an isolated community without recognition or support, infuse these prayers with such depth and passion? Were they perhaps an offshoot of the Lemba, a group in southern Africa who carry a genetic link that ties them to Aaron, the brother of Moses? I couldn't make sense of this. I could not place this music coming from the Uganda that I have visited in the 1990s, when I spent two weeks there taking photographs for a book on conservation work in Queen Elizabeth National Park. Living with rangers and local villagers and sharing communal meals and long walks together, I thought that I had a fairly good sense of Uganda and its people. That music, and those questions, inspired me to undertake another journey, this time to the rolling hills of eastern Uganda.

During my previous visits, I had found Uganda's people to be friendly and open. On buses or in restaurants I observed that they easily made casual conversation. They were particularly eager to chat with foreign visitors and inquire into their health and well-being. Once a comfortable rapport was established, eventually the topic of religion would come up. For me this turned into a little game. Here is how it would go. “Jewish,” I would respond, looking straight back into his open eyes, waiting as I watched him think—but the only answer would be a blank stare. I would prolong the silence for several minutes and then say, “the Hebrews” Still, there would be no response until, inevitably the Ugandan would say something like, “I am not familiar with that one. You mean, like with Buddha?”

“No,” I would reply. “No Buddhas here.” Now, hoping to move things along, I would say, “Like in Israel. The children of Abraham,” and finally there would be a nod of understanding because of my reference to the Bible. Each time the conversation ended there, and the subject was changed. Jews seemed to be too foreign or exotic, certainly not part of mainstream Ugandan Society.

And yet, just four hours after leaving Kampala on my journey to eastern Uganda, my insides still reeling from being tossed about on mud-slide roads, I discovered five tiny enclaves, each with its own mud-walled synagogue nestled amid banana and bean fields.

Discovering the Abayudaya

Rural Africa has a remarkably consistent look and feel. From region to region, whether in the Congo or Cameroon, Zambia or South Africa, Kenya or Uganda, one can see the same mud huts, the same golden light and dusty haze, the same barefoot children and scrawny chickens running into each other's tracks. Settlement after settlement dominates the landscape. Women and children with water jugs on their heads walk along the narrow dirt tracks, passing by well-built men carrying garden hoes or machetes. The wild animals that once roamed free have long since retreated to the national parks and game reserves. Few local tribal customs remain intact. Lulled into a sense of sameness on my long journey from the bush, I found it all the more remarkable to behold, standing in the shadow of Mount Elgon in eastern Uganda, the villages of the Abayudaya, the Jews of Uganda. (Literally, Abayudaya means “the Jews” in Luganda, the local language.) Here, this tight community continues to practice a set of traditions that date back three thousand years, traditions once observed by followers of Moses in North Africa. In effect, the Abayudaya have reconnected Judaism with its African roots.

The 600-plus members of the Abayudaya community in Uganda lead a life devoted to Jewish observance. Like observant Jews around the world, they keep kosher households. Each week they read from scriptures in the Torah (the five books of Moses), and they follow the strict laws of the Shabbat (the Sabbath). They circumcise their sons on the eighth day after birth. Abayudaya women obey traditional laws concerning purity and abstinence during their menstrual period. The Abayudaya observe the same holidays, rules, and commandments as Jews in other communities. In fact, having created their religious identity in virtual isolation and remaining steadfast to their beliefs through Idi Amin’s reign of terror, when synagogues were closed and prayers has to be held in secret, they are even more observant than most Jews.

The Hidden Tribe: The Story of the Jews of Uganda

In August 1999 a graduate student in anthropology at Boston University gave me a recording of Hebrew prayers chanted by the Abayudaya, a community of Bantu Jews from a remote region of Uganda. The melodies were a haunting blend of traditional Hebrew songs and rich African harmonies. I play this recording again and again, puzzling over its origins. How could this group of African Jews come to be? And how could an isolated community without recognition or support, infuse these prayers with such depth and passion? Were they perhaps an offshoot of the Lemba, a group in southern Africa who carry a genetic link that ties them to Aaron, the brother of Moses? I couldn't make sense of this. I could not place this music coming from the Uganda that I have visited in the 1990s, when I spent two weeks there taking photographs for a book on conservation work in Queen Elizabeth National Park. Living with rangers and local villagers and sharing communal meals and long walks together, I thought that I had a fairly good sense of Uganda and its people. That music, and those questions, inspired me to undertake another journey, this time to the rolling hills of eastern Uganda.

During my previous visits, I had found Uganda's people to be friendly and open. On buses or in restaurants I observed that they easily made casual conversation. They were particularly eager to chat with foreign visitors and inquire into their health and well-being. Once a comfortable rapport was established, eventually the topic of religion would come up. For me this turned into a little game. Here is how it would go. “Jewish,” I would respond, looking straight back into his open eyes, waiting as I watched him think—but the only answer would be a blank stare. I would prolong the silence for several minutes and then say, “the Hebrews” Still, there would be no response until, inevitably the Ugandan would say something like, “I am not familiar with that one. You mean, like with Buddha?”

“No,” I would reply. “No Buddhas here.” Now, hoping to move things along, I would say, “Like in Israel. The children of Abraham,” and finally there would be a nod of understanding because of my reference to the Bible. Each time the conversation ended there, and the subject was changed. Jews seemed to be too foreign or exotic, certainly not part of mainstream Ugandan Society.

And yet, just four hours after leaving Kampala on my journey to eastern Uganda, my insides still reeling from being tossed about on mud-slide roads, I discovered five tiny enclaves, each with its own mud-walled synagogue nestled amid banana and bean fields.

Discovering the Abayudaya

Rural Africa has a remarkably consistent look and feel. From region to region, whether in the Congo or Cameroon, Zambia or South Africa, Kenya or Uganda, one can see the same mud huts, the same golden light and dusty haze, the same barefoot children and scrawny chickens running into each other's tracks. Settlement after settlement dominates the landscape. Women and children with water jugs on their heads walk along the narrow dirt tracks, passing by well-built men carrying garden hoes or machetes. The wild animals that once roamed free have long since retreated to the national parks and game reserves. Few local tribal customs remain intact. Lulled into a sense of sameness on my long journey from the bush, I found it all the more remarkable to behold, standing in the shadow of Mount Elgon in eastern Uganda, the villages of the Abayudaya, the Jews of Uganda. (Literally, Abayudaya means “the Jews” in Luganda, the local language.) Here, this tight community continues to practice a set of traditions that date back three thousand years, traditions once observed by followers of Moses in North Africa. In effect, the Abayudaya have reconnected Judaism with its African roots.

The 600-plus members of the Abayudaya community in Uganda lead a life devoted to Jewish observance. Like observant Jews around the world, they keep kosher households. Each week they read from scriptures in the Torah (the five books of Moses), and they follow the strict laws of the Shabbat (the Sabbath). They circumcise their sons on the eighth day after birth. Abayudaya women obey traditional laws concerning purity and abstinence during their menstrual period. The Abayudaya observe the same holidays, rules, and commandments as Jews in other communities. In fact, having created their religious identity in virtual isolation and remaining steadfast to their beliefs through Idi Amin’s reign of terror, when synagogues were closed and prayers has to be held in secret, they are even more observant than most Jews.