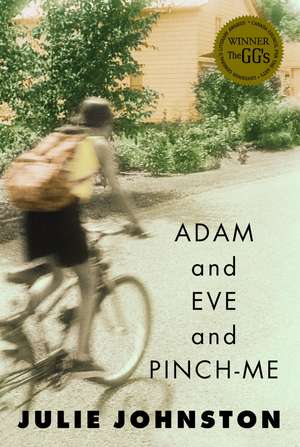

Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me

Autor John Ed. Johnston, Julie Johnstonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2003 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Sara Moone is an expert on broken hearts. She is a foster child who has been bounced from home to home, but now she is almost sixteen and can not live in the system forever. She vows that she will live in a cold, white place where nobody can hurt her again.

But there is one more placement in store for Sara. She is sent to live with the Huddlestons on their sheep farm. There, despite herself, Sara learns that there is no escape from love. It has a way of catching you off guard, even when you try to turn your back.

When it was published in 1994, Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me won every major children’s book award in Canada. Since then it has appeared in countries around the world. Its story of love and longing strikes a universal chord.

Preț: 57.40 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 86

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.98€ • 11.45$ • 9.13£

10.98€ • 11.45$ • 9.13£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780887766480

ISBN-10: 088776648X

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 133 x 195 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

ISBN-10: 088776648X

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 133 x 195 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

Notă biografică

Julie Johnston received the Governor General’s Award for these her first two books. Her third novel, The Only Outcast, was short-listed for the Governor General’s Award, as was her most recent book, In Spite of Killer Bees. Julie Johnston lives in Peterborough, Ontario.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

Just shut up. I’d like to tell my brain to just shut up. Have you ever noticed how you can’t make your mind stop thinking even though you try to think about absolutely nothing? You still keep on thinking about how you’re trying to think about nothing because you want to avoid thinking about the thing you don’t want to think about? Oh, shut up.

I appear to be talking to a machine.

I can blank out people. Wipe them right off the board. Paint over them. Close the book on them. Click, erase, gone. It’s me I’m having trouble escaping. A computer is very close to perfection. I love the way you can press cancel or delete and it actually happens. To the printed word, that is.

I’m leaving this place. Mrs. K. and Frank are past tense. It’s not breaking my heart to leave because as a ward of the Children’s Aid I’m used to it. Any idea what that means? Not bloody likely.

Here’s a hint. What do you do with something you don’t want? Throw it out, of course. And what do you call the junk you throw out? You got it.

I’m losing it, obviously. Do I expect this machine to give answers?

My new address will be: Sara Moone, c/o E. Huddleston, RR 3, Ambrose, Ontario. An easy address compared to this one: c/o Mrs. Avartha Koscyzstin, 319 Campagnola Street East, North Malverington, Ontario. And let’s see, what was the one before that? Station Road. No number. That was the Lomers, I think. The only thing I remember about that place was, Arn never laid a hand on us kids. He made us memorize that statement. Sonia, his wife, got slapped around on a regular basis, however.

I have no idea exactly how many foster homes I’ve been in. I was in a group home once and hated it more than anything. Kids kept stealing my stuff. I hide everything now, money especially. Having my own money is very important to me.

A lot of cruelty went on in that place. One of the older kids broke my finger by tricking me. “Put your finger in the crow’s nest,” he said, “the crow’s not at home.” So, like a sucker, I stuck my finger into his big, crunching fist. My finger’s still crooked. I used to get sucked in by Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, too. Until I found out the right answer.

Don’t plan on digesting my whole life story here, because I’ve forgotten most of it. And what I remember would bore the brains out of a dead cow. I came to stay with Mrs. K. (everybody calls her Mrs. K., including Frank, her elderly husband) when I was about thirteen. I’m fifteen now. That’s the longest I’ve stayed anywhere. I’ll be sixteen at the end of August and then kaboom. I start living. No more social workers. No more foster parents. No more school. I will be me, alone, untouchable.

I’d better start packing. They took Mrs. K. off to the hospital about an hour ago, although she wasn’t supposed to have her operation until next month. “I’m a bit sickly,” she always said to me. Sickly! She’s been at death’s door since day one. There were times when I wouldn’t have minded nudging her right through it. I’ve been playing nursemaid here for the past year and a half, almost. Oh well, so what? It’s February, which means only six months left in limbo. I can hardly wait to start my life.

I’ve got everything packed except this machine. One suitcase and one cardboard box hold the contents of my socalled existence. Another cardboard box contains my books. My other existences. I’ve got my money pinned to my underwear. Frank said he’d carry down my stuff. I said forget it. The stuff weighs more than he does. Especially the books. Frail old Frank, sitting down there by the window in his LaZBoy, waiting for Ruth to pick me up so he can go and sit in a chair at the hospital and listen to Mrs. K. belch and moan about how sickly she is. “I’ll be along later, love,” he said to her. Love! How pathetic!

However, I will say this about old Frank, he’s generous.

“Take the computer with you,” he said.

I said, “You’re kidding!”

“Why would I be kidding?” he said. He’s just retired and the place where he used to work bought all new computers so he got a deal on this old one. “Maybe you’ll relate to it, because, God knows, you don’t relate to people.” Suddenly he’s a psychologist. Frank Freud. I hate that. I hate when people think they have you figured out. Of course I don’t relate to people. Why would I? I’m not related to anybody and nobody’s related to me.

Ruth insists this is not true. ShutupshutupshutUP.

Forget it. That’s what I don’t want to think about. Ruth’s here. I have to unplug this thing and lug it out to her car. She’s my case worker and will be driving me to my new foster home. I’m pressing exit. Yes I’ll save this. Temporarily.

***

O give me a home where the imbeciles roam – I can’t believe this place. A farm! They’ve placed me at some kind of a farm. Am I being punished? Do they think I have animalistic tendencies? I mean, look! I’ve never done anything wrong in my life. I obey every rule in the book. The way to get along in this world is be invisible. Flatten yourself out and wait. That’s what I thought I was doing. Just hanging around blending in with the wallpaper, waiting until my sixteenth birthday. I thought it was my darkest hour when I ended up with Mrs. K. and Frank exuding compassion for the homeless in their house haunted by every cabbage they’d ever boiled in their lives. They went in for boiled fish, too, and deeply waxed floors and they were death on open windows. But this place!

Actually the house smells okay. It smells like the inside of a bakery, which is not too hard to take. Outside is a different story. They insisted on showing me a bunch of beadyeyed chickens and a barn full of decaying sheep. When I held my nose, they laughed and said I’d get used to it. I said, “Don’t bet on it,” but they didn’t hear me. I have this affliction. When I talk to strangers, I sound as though I’m trying out my voice for the first time.

These people have some kind of a mangy old dog that sidled up to me and put its head under my hand. I mean, what was I supposed to do? I’m no great lover of animals, but it seems a natural reaction to pat a dog’s head if it’s right there under your hand. “Don’t pat the dog!” somebody yelled at me. “Is this a nnnnut house?” I tried to ask them, my other affliction making its presence known.

“Nnno, it’s the loony bbbin!” shrieked this jerkass kid, who ran before I could grab him and tear the living mouth right off his face.

But wait. I’ll go back to this afternoon. Ruth and I clunking along in her car heading out of town. No heater. Weather cold as a witch’s tit. Slithering around icy corners. No treads on the tires. Me, minding my own business, not saying anything, even though Ruth is one of the few people I can talk to without sounding as though cracker crumbs are stuck in my throat, and looking out through a little patch on my window I’d defrosted with my bare fist. I was watching the houses peter out until there was nothing left but field after snowy field of nothingness. Ruth said, “How do you feel about moving to a new place?”

“Okay,” I said. She tried to give me one of those indepth eyecontact looks but gave it up when we started to go into a skid. She was managing to get enough warm air blowing onto the windshield to give her an eggshaped view. She decided to look at the road.

“How do you feel about leaving the Koscyzstin’s?”

“Okay,” I said.

“It’s too bad about Mrs. K. If we could have avoided this move we would have, but the situation looked pretty hopeless. I’m sorry about your friends.”

“Friends?”

“You’ll miss your school buddies.”

“Oh. Right.” The best way to handle Ruth is tell her what she wants to hear. She’s spent her entire adult life picking over misery, sorting out disasters, trying to bring a little joy into people’s lives. Why burden her with my lack of friends?

“Are you happy, Sara?”

“Intensely.” She was trying to look at me again, so I gave her my LittleOrphanAnnie look. Like the comic strip character with zeros for eyes?

We drove along, leaving the flat fields behind, and started chugging up and down some serious hills. The road narrowed and became lined with trees. A wall of trees. We were surrounded, boxed in, by some kind of primeval forest. Deep, impenetrable, hostile. Ruth was still going on about my friends and wanting me to talk about myself. I told her I thought I was coming down with laryngitis. What’s there to tell, anyway? She must have a file describing the vital statistics of Sara Moone, height, weight, etcetera. All she has to do is look me up on her computer if she wants to know what I’m like. What she sees is what I am. Tallish. Thinnish. Reddish of hair. Distinguishing features? None. No, maybe they keyed in burn scars, left leg. That sums up Sara Moone.

Ruth didn’t believe I was coming down with laryngitis. “Tell me about your school friends,” she said.

If I’ve learned one thing in my life it’s this: if you don’t want your heart broken, don’t let on you have one. It’s the motto I live by. It allows me to keep my personality flat. No heart, no brains, no guts. At school this girl who sat in front of me in computer class asked me over to her house one day. At first my insides started knotting up, and I thought I’d puke right in front of her until I remembered I had no guts. “C-can’t,” I said and walked away. How could I? What would be the point? The girl would find out that I had about as much substance as a dropped ice cube, that I wasn’t based on anything, and that would be the end of it. I’m disposable. “Can’t make it,” I always say. I don’t make excuses; I never aim for a soft little smile of regret. I am so incredibly cool it’s becoming my trademark. I only have one problem. After I say no, after I turn people down, just seconds later, I sometimes think I have become solidified, fixed. One of my foster things once yelled at me, “Your face is gonna freeze like that!” I think I was trying to look like an attack dog with rabies. Frozen. That’s the way I feel after I say no. I’ve become frozen – in a negative position. Then the feeling goes and I can move.

Ruth was still waiting for me to tell her about my friends. “A fun-loving and loyal group,” I said. She shook her head and frowned into the darkening afternoon. It was starting to snow. Sherwood forest was easing up a bit. The road ran crookedly between pink slabs of rock. It could have been chiseled piece by piece out of the hill by some sculptor obsessed by a single idea: Get to the other side! Find a way through!

“I’m not trying to pry, you know,” Ruth said. “I just want to get to know you a little bit better. What do you do when you’re not in school?”

“Drugs.” I was making another peephole with the palm of my hand, but I sensed by the way we slid into another skid that she was looking at me instead of the road. “Kidding,” I said. I was, too. Only dimwits and emotional screwups do drugs. Fortunately, I am neither.

I could see a few scrubby farms, now, poked into the frosty hills, some with lights on as if they were expecting someone to drop in. Or hoping.

“Seriously,” she said, “do you have any hobbies?”

“A little embroidery now and then. Paint-by-numbers. Candy striping.”

“I said seriously.”

“Teaching Sunday school.”

“Sara!”

“Of course I don’t have any hobbies. What do you take me for?”

At the Koscyzstin’s, I used to spend weekend after blank weekend just sitting around listening for Mrs. K.’s next feeble request and waiting for time to pass. I admit I did a lot of reading – everything I could lay my hands on, novels, magazines, newspapers, cereal boxes. I get involved in books to the point where it becomes embarrassing. When I read The Secret Garden, I began to sound quite snotty. When I read The Color Purple, I developed a southern drawl. I’m not safe around books.

Sometimes I spend time studying, not to pull off high marks, which I get whether I study or not, but because I like knowing things. Knowing things will allow me to survive when I start my life. That and money.

Mrs. K. was never what you’d call a robust woman, up and down with one ailment or another over most of those two years. “Do you think you could come straight home after school?” she’d say with her voice one notch away from a whine. “I couldn’t get up the steam to start hoovering the rugs at all yesterday, and they’re just thick.” Or she’d say, “Don’t make any plans for Saturday, I’ve a list for you a mile long. It just gives me the pip thinking about it.” She’d sit there casting her gloomy eye on me, rubbing her belly. And then she’d ease out these long and mournful belches. “Now stay within earshot, Sara,” she used to say. “You never know when I might need something from the drug store.”

But big deal, so what? Being bogged down with household chores didn’t kill me. I got kind of used to running errands and carrying bowls of pale soup and plates of dry toast to her. I’m not complaining. I didn’t exactly feel sorry for the old girl. I felt sort of … responsible. Who else did she have? Frail Frank? Anyway, why would I need friends cluttering up my present life? Reality starts at sixteen.

Picture me as something like a little hyphen on a blank screen. A cursor. Unattached to anything before or after. I move along and down, along and down, until finally I get to page sixteen. That’s when the story starts. Me, alone, in a very sturdy, very compact, glass fortress where I can see out but no one can see beyond the surface. Queen of cool. Of course I’ll need a job because I haven’t been able to save much money, but I’m not fussy. Night watchman at the morgue would suit me fine.

My real dream is this: I’m going up north, as far north as I can go and still get a job, some remote outpost where I’ll have my own space unshared by any other human being. I might have a dog. One of those Huskies, intelligent and loyal. I would like to be a pilot who flies supplies into even more remote places.

“I think you’ll like the Huddlestons’,” Ruth said. “There are other kids there. A ready-made family for you.”

No clutter. No noise. No responsibilities.

“Two boys younger than you.”

“O joy divine.” I took off my glove again and pressed my hand against my side of the windshield to broaden my horizons. Nothing to see except angry snowflakes attacking horizontally and disappearing. The road was becoming narrower and more twisted. We were beyond the boonies. Way beyond. “Turn on your headlights,” I said.

“They’re on.”

I’ve never driven a car, but I know I could do it. Ruth, on the other hand, seems to have skipped driver’s ed. She was intent on putting us in the ditch. She kept turning the wheel too far coming out of a skid, which any damn fool knows – But who cares? I didn’t.

Ruth glanced at me a couple of times as if she had something important to say but didn’t know how to start. Finally, she said, “I’m not trying to pressure you, but couldn’t you agree to read one letter from your mother? It’s been over a year now since she contacted us, looking for you. You’re under no obligation to answer it. But maybe you should give her half a chance to prove herself. You’re prejudging her.”

“She prejudged me.”

“Oh, stop. You know as well as I do how many reasons there are for a woman to give up a baby.”

“None of them good, if you happen to be the baby. Ex-baby.”

“You were adopted immediately. You know that.”

“I don’t remember. Anyway, big deal. They died.”

“Sara. They didn’t do it on purpose.”

“I didn’t say they did.”

“Well, you sound so – The fire was a tragic accident. It wasn’t anyone’s fault. No one set out to deprive you, personally, of a home and a family. It was one of those things.”

“I’m not really interested in pursuing this any further.”

Ruth heaved one of her big, dramatic sighs as if she were going to let the subject drop. But no. “I really should confess,” she said, “that your mother knows you are moving to the Ambrose area.”

“How come? Is there some sort of conspiracy against me? Why are you trying to spoil my life?”

“I didn’t do it,” Ruth said. “But I’m afraid the information got leaked out by mistake. We had temporary help for a while – and the woman is persistent. The last time she contacted me she said she intended to ask everyone in the whole county, if necessary, to track down the family who had adopted her daughter.”

“What’s her point?”

“Your well-being, I gather. She wants to see if you’re happy, and to let you know she’s out there. Seems harmless enough.”

I stared into the ranks of snowflakes driving against the windshield and tried to make out a formation, some pattern, but it only made me dizzy. “Wait a minute,” I said. “I’m not adopted. She’s looking for some kid who’s adopted, and that ain’t me.” I smiled. Safe. Anonymous. “Right?”

Ruth glanced at me and we narrowly missed a snowbank. “You might want a mother someday.”

“I’ll be the judge of that. What does this woman look like?” If I was going to be involved in some kind of cloak-and-dagger chase, I needed a running start. Ruth didn’t know, as it turned out, nor did the woman have a picture of me.

I do have one thing, however, which I’ve never told anyone about. The ad.

Sitting beside Ruth, I returned to my dream of being sixteen, of splitting off, separating myself from people. All people. What I want is sole control of Sara Moone, because up to now my life has had no more importance to anyone than a scrap of paper, scribbled on, torn up, thrown away, burned to an ash. I have never had a say in what happens to me. When I was eight, my foster mother at the time became pregnant with twins. She sat me down for a heart-to-heart talk about this. I was so excited about the twin babies we were going to have that I didn’t hear her tell me that she was giving me back to the Children’s Aid. I was grinning away like an idiot, thinking about how I’d get to feed the babies their bottles, and she was saying, “I’m very sorry, I don’t know what else I can do.” And things like that. And I just stood there when it finally sank in, my lips frozen in a wide stretch across my face and my eyes turning into round empty circles. In my next home, my foster mother was ruled unfit and the family fell apart. Then there was another one, and another, until I stopped being able to sort them out. I’ve been plucked up, plunked down, shuffled and re-dealt so many times my mind refuses to remember it all.

However, sixteen is the magic age. That’s when I can legally drop out of school, legally drop out of foster homes … and legally drop off the edge of the world, I guess, for all anyone would care.

“I really care what happens to you, you know,” Ruth said. She looked at me quickly and then back at the road. We were at the top of a long, slow grade lightly dusted with snow. “You could write to me.”

“And say what?”

“Tell me how you feel about things, about what your life is like. You have that computer; you might as well put it to good use.”

“Can’t. I don’t have a printer. Even if I did, it wouldn’t do you any good. I don’t feel anything about anything, so you’d get nothing but blank pages.” Actually I was beginning to feel us going into a slide down this hill. Ruth felt it, too, and hit the brakes. We did a slow-motion, complete spin and drifted off the road nose-first into the ditch.

“Oh, great,” Ruth said.

“Any survivors?” I said.

She tried gunning the engine. The wheels spun uselessly. “What are we going to do? We’re miles from anywhere.” Her purse was on the seat between us. She opened it and started rummaging around. She took out a package of cigarettes and a lighter.

The inside of the car seemed incredibly small all of a sudden. “What are you doing?”

She started lighting her cigarette. “Do you mind?”

The lighter was turned up too high. I could see her face, her eyes questioning mine, wondering if I minded her smoking, but hoping I didn’t because she needed to smoke, and her hair, pale brown, like dried grass, wisping out from under her green knitted hat toward the flame. The way the flame flared up, I don’t know, I guess it made me panic. I may have screamed. I yelled, anyway, because Ruth jumped and her cigarette flipped out from between her fingers. I saw a rain of sparks in front of the flare from the lighter and I – Forget it.

I got out of the car. Smoke inside a car is sickening.

I remember Ruth running after me. The two of us standing in the middle of snowy nowhere shouting at each other. She tried to put her arm around me, but I gave her a shove and then the bus came along. Out of the white screen of blowing snow, headlights. And Ruth sprawled on the road in its path. One instant Ruth was lit up and the next she was in semi-darkness as the bus’s headlights swerved from side to side down that glassy hill with the tortured sound diesel brakes have drowning out everything else. I grabbed her arm and yanked her into the ditch as the bus crunched past and came to a stop a little farther along the road.

***

It’s fairly quiet here, now, at Château Huddleston, except for me clicking away on this machine. Supper was a major ordeal. Food has never been a big item in my life. Here, however, quantity is everything. God knows what the quality is like. I didn’t eat enough of whatever was being served to tell. After they’d all sucked back about forty tons of unidentifiable, gravy-covered, cooked objects, they paused long enough to breathe and looked at my plate, still brimful. “Edith-Ann will like it,” someone said. Whoever that is. Probably some idiot daughter locked in the attic. This would not be entirely out of the question.

The lord of the manor has retired as has his charming wife. The two delightful foster sons have gone beddy-bye in the room next to mine after surgically removing each other’s windpipes, I gather. They were fighting over a jackknife and then one of them started choking and coughing until Ma (can you dig it?) Huddleston put a stop to it. “And no dessert for three days,” she said. I can’t believe this place.

I see I left off when the bus came along. I was interrupted. No such thing as privacy around here.

To go back: It was the Ottawa bus and we got on. Ruth told the driver where we were going and he said that was his next stop. Sitting beside each other in the last two seats on the bus, we didn’t have a whole lot to say. Pressed close to the window, I looked out. The snow had stopped coming down and was just blowing around now. I’d already told Ruth I was sorry. I was, too. I hadn’t meant to shove her under a bus. I’m cool, but I’m no murderer. “I’m sorry, too,” she’d said. “I should have remembered that you don’t like to be touched.”

Elbows tucked into my rib cage, legs tight against the bus heater, I ignored her remark. Through the bus window I watched the clouds part, revealing the moon, a mean little curved blade slung low in the darkening sky. It was following us.

Fifteen minutes later the bus pulled into the Elite Cafe and Bus Terminal on the edge of the town of Ambrose. “You go inside there,” the bus driver said to Ruth as we stepped down out of the bus into the snowy bluster. “They’ll call you a tow truck and you can get a coffee while you wait.” The bus door eased to, then snapped closed, and the bus disappeared into a turmoil of exhaust and snow.

We looked at each other and shrugged. You could hardly see in through the windows, they were so fogged up. Inside, the warmth of the place almost wrapped itself around us with steam coming up from pots of coffee behind the counter and a frazzle-haired waitress filling the cups of a few old geezers sitting on stools gabbing their heads off, their big coats hanging open. Fluorescent lights beat down on them like a sunny day. A couple of tables stood empty under the windows. I slid into a chair beside one and waited for Ruth to ask the waitress about a tow truck.

Everybody stopped talking to listen in. “Where am I phoning from?” Ruth called to the waitress from the pay phone on the wall. “Ee-lite Cafe out on the number seven. He knows where it is.”

“Not a night to be out on the road,” one of the patrons of the Ee-lite Cafe said to no one in particular.

“That skiffle o’ snow on top o’ the glare ice just slicks her down good,” someone else said.

“D’y’ mind the time we froze up after a long thaw and we were froze up so good there wasn’t hardly a toilet’d flush in the entire county? Two year ago now, it was.”

“It wasn’t neither. It was last spring.”

Ruth went back to the counter to get change for another call and they all shut up again.

“Mr. Huddleston?” Ruth was saying into the phone. “Ruth Petrie from the Children’s Aid. I wonder if you could come into the Elite, uh, Ee-lite Cafe to pick up Sara. I’ve put my car in the ditch.” A pause. “Your foster daughter. Sara Moone.”

Meanwhile I was cringing, trying to disappear into the furniture. Obviously I hadn’t been programmed into Mr. Huddleston’s memory. When I looked up all I could see was a row of eyes staring at me from the mirror above the counter. I turned to the window but I couldn’t see out.

“Yes.” Relief in her voice. “Yes, that’s right.”

The software must have kicked in.

After she hung up, Ruth got us both coffee and then she went to the washroom. There was a general buzz of conversation, some of which I caught.

“Bears for punishment, aren’t they.”

“Oh, I don’t know. Hud, he’s got a firm hand there.”

“Missus is a bit soft.”

“A bit soft. Salt o’ the earth, though.”

“Oh, salt o’ the earth, no question. But why they keep takin’ in them kids, I’ll never tell y’.”

“Bears for punishment.”

Just shut up. I’d like to tell my brain to just shut up. Have you ever noticed how you can’t make your mind stop thinking even though you try to think about absolutely nothing? You still keep on thinking about how you’re trying to think about nothing because you want to avoid thinking about the thing you don’t want to think about? Oh, shut up.

I appear to be talking to a machine.

I can blank out people. Wipe them right off the board. Paint over them. Close the book on them. Click, erase, gone. It’s me I’m having trouble escaping. A computer is very close to perfection. I love the way you can press cancel or delete and it actually happens. To the printed word, that is.

I’m leaving this place. Mrs. K. and Frank are past tense. It’s not breaking my heart to leave because as a ward of the Children’s Aid I’m used to it. Any idea what that means? Not bloody likely.

Here’s a hint. What do you do with something you don’t want? Throw it out, of course. And what do you call the junk you throw out? You got it.

I’m losing it, obviously. Do I expect this machine to give answers?

My new address will be: Sara Moone, c/o E. Huddleston, RR 3, Ambrose, Ontario. An easy address compared to this one: c/o Mrs. Avartha Koscyzstin, 319 Campagnola Street East, North Malverington, Ontario. And let’s see, what was the one before that? Station Road. No number. That was the Lomers, I think. The only thing I remember about that place was, Arn never laid a hand on us kids. He made us memorize that statement. Sonia, his wife, got slapped around on a regular basis, however.

I have no idea exactly how many foster homes I’ve been in. I was in a group home once and hated it more than anything. Kids kept stealing my stuff. I hide everything now, money especially. Having my own money is very important to me.

A lot of cruelty went on in that place. One of the older kids broke my finger by tricking me. “Put your finger in the crow’s nest,” he said, “the crow’s not at home.” So, like a sucker, I stuck my finger into his big, crunching fist. My finger’s still crooked. I used to get sucked in by Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, too. Until I found out the right answer.

Don’t plan on digesting my whole life story here, because I’ve forgotten most of it. And what I remember would bore the brains out of a dead cow. I came to stay with Mrs. K. (everybody calls her Mrs. K., including Frank, her elderly husband) when I was about thirteen. I’m fifteen now. That’s the longest I’ve stayed anywhere. I’ll be sixteen at the end of August and then kaboom. I start living. No more social workers. No more foster parents. No more school. I will be me, alone, untouchable.

I’d better start packing. They took Mrs. K. off to the hospital about an hour ago, although she wasn’t supposed to have her operation until next month. “I’m a bit sickly,” she always said to me. Sickly! She’s been at death’s door since day one. There were times when I wouldn’t have minded nudging her right through it. I’ve been playing nursemaid here for the past year and a half, almost. Oh well, so what? It’s February, which means only six months left in limbo. I can hardly wait to start my life.

I’ve got everything packed except this machine. One suitcase and one cardboard box hold the contents of my socalled existence. Another cardboard box contains my books. My other existences. I’ve got my money pinned to my underwear. Frank said he’d carry down my stuff. I said forget it. The stuff weighs more than he does. Especially the books. Frail old Frank, sitting down there by the window in his LaZBoy, waiting for Ruth to pick me up so he can go and sit in a chair at the hospital and listen to Mrs. K. belch and moan about how sickly she is. “I’ll be along later, love,” he said to her. Love! How pathetic!

However, I will say this about old Frank, he’s generous.

“Take the computer with you,” he said.

I said, “You’re kidding!”

“Why would I be kidding?” he said. He’s just retired and the place where he used to work bought all new computers so he got a deal on this old one. “Maybe you’ll relate to it, because, God knows, you don’t relate to people.” Suddenly he’s a psychologist. Frank Freud. I hate that. I hate when people think they have you figured out. Of course I don’t relate to people. Why would I? I’m not related to anybody and nobody’s related to me.

Ruth insists this is not true. ShutupshutupshutUP.

Forget it. That’s what I don’t want to think about. Ruth’s here. I have to unplug this thing and lug it out to her car. She’s my case worker and will be driving me to my new foster home. I’m pressing exit. Yes I’ll save this. Temporarily.

***

O give me a home where the imbeciles roam – I can’t believe this place. A farm! They’ve placed me at some kind of a farm. Am I being punished? Do they think I have animalistic tendencies? I mean, look! I’ve never done anything wrong in my life. I obey every rule in the book. The way to get along in this world is be invisible. Flatten yourself out and wait. That’s what I thought I was doing. Just hanging around blending in with the wallpaper, waiting until my sixteenth birthday. I thought it was my darkest hour when I ended up with Mrs. K. and Frank exuding compassion for the homeless in their house haunted by every cabbage they’d ever boiled in their lives. They went in for boiled fish, too, and deeply waxed floors and they were death on open windows. But this place!

Actually the house smells okay. It smells like the inside of a bakery, which is not too hard to take. Outside is a different story. They insisted on showing me a bunch of beadyeyed chickens and a barn full of decaying sheep. When I held my nose, they laughed and said I’d get used to it. I said, “Don’t bet on it,” but they didn’t hear me. I have this affliction. When I talk to strangers, I sound as though I’m trying out my voice for the first time.

These people have some kind of a mangy old dog that sidled up to me and put its head under my hand. I mean, what was I supposed to do? I’m no great lover of animals, but it seems a natural reaction to pat a dog’s head if it’s right there under your hand. “Don’t pat the dog!” somebody yelled at me. “Is this a nnnnut house?” I tried to ask them, my other affliction making its presence known.

“Nnno, it’s the loony bbbin!” shrieked this jerkass kid, who ran before I could grab him and tear the living mouth right off his face.

But wait. I’ll go back to this afternoon. Ruth and I clunking along in her car heading out of town. No heater. Weather cold as a witch’s tit. Slithering around icy corners. No treads on the tires. Me, minding my own business, not saying anything, even though Ruth is one of the few people I can talk to without sounding as though cracker crumbs are stuck in my throat, and looking out through a little patch on my window I’d defrosted with my bare fist. I was watching the houses peter out until there was nothing left but field after snowy field of nothingness. Ruth said, “How do you feel about moving to a new place?”

“Okay,” I said. She tried to give me one of those indepth eyecontact looks but gave it up when we started to go into a skid. She was managing to get enough warm air blowing onto the windshield to give her an eggshaped view. She decided to look at the road.

“How do you feel about leaving the Koscyzstin’s?”

“Okay,” I said.

“It’s too bad about Mrs. K. If we could have avoided this move we would have, but the situation looked pretty hopeless. I’m sorry about your friends.”

“Friends?”

“You’ll miss your school buddies.”

“Oh. Right.” The best way to handle Ruth is tell her what she wants to hear. She’s spent her entire adult life picking over misery, sorting out disasters, trying to bring a little joy into people’s lives. Why burden her with my lack of friends?

“Are you happy, Sara?”

“Intensely.” She was trying to look at me again, so I gave her my LittleOrphanAnnie look. Like the comic strip character with zeros for eyes?

We drove along, leaving the flat fields behind, and started chugging up and down some serious hills. The road narrowed and became lined with trees. A wall of trees. We were surrounded, boxed in, by some kind of primeval forest. Deep, impenetrable, hostile. Ruth was still going on about my friends and wanting me to talk about myself. I told her I thought I was coming down with laryngitis. What’s there to tell, anyway? She must have a file describing the vital statistics of Sara Moone, height, weight, etcetera. All she has to do is look me up on her computer if she wants to know what I’m like. What she sees is what I am. Tallish. Thinnish. Reddish of hair. Distinguishing features? None. No, maybe they keyed in burn scars, left leg. That sums up Sara Moone.

Ruth didn’t believe I was coming down with laryngitis. “Tell me about your school friends,” she said.

If I’ve learned one thing in my life it’s this: if you don’t want your heart broken, don’t let on you have one. It’s the motto I live by. It allows me to keep my personality flat. No heart, no brains, no guts. At school this girl who sat in front of me in computer class asked me over to her house one day. At first my insides started knotting up, and I thought I’d puke right in front of her until I remembered I had no guts. “C-can’t,” I said and walked away. How could I? What would be the point? The girl would find out that I had about as much substance as a dropped ice cube, that I wasn’t based on anything, and that would be the end of it. I’m disposable. “Can’t make it,” I always say. I don’t make excuses; I never aim for a soft little smile of regret. I am so incredibly cool it’s becoming my trademark. I only have one problem. After I say no, after I turn people down, just seconds later, I sometimes think I have become solidified, fixed. One of my foster things once yelled at me, “Your face is gonna freeze like that!” I think I was trying to look like an attack dog with rabies. Frozen. That’s the way I feel after I say no. I’ve become frozen – in a negative position. Then the feeling goes and I can move.

Ruth was still waiting for me to tell her about my friends. “A fun-loving and loyal group,” I said. She shook her head and frowned into the darkening afternoon. It was starting to snow. Sherwood forest was easing up a bit. The road ran crookedly between pink slabs of rock. It could have been chiseled piece by piece out of the hill by some sculptor obsessed by a single idea: Get to the other side! Find a way through!

“I’m not trying to pry, you know,” Ruth said. “I just want to get to know you a little bit better. What do you do when you’re not in school?”

“Drugs.” I was making another peephole with the palm of my hand, but I sensed by the way we slid into another skid that she was looking at me instead of the road. “Kidding,” I said. I was, too. Only dimwits and emotional screwups do drugs. Fortunately, I am neither.

I could see a few scrubby farms, now, poked into the frosty hills, some with lights on as if they were expecting someone to drop in. Or hoping.

“Seriously,” she said, “do you have any hobbies?”

“A little embroidery now and then. Paint-by-numbers. Candy striping.”

“I said seriously.”

“Teaching Sunday school.”

“Sara!”

“Of course I don’t have any hobbies. What do you take me for?”

At the Koscyzstin’s, I used to spend weekend after blank weekend just sitting around listening for Mrs. K.’s next feeble request and waiting for time to pass. I admit I did a lot of reading – everything I could lay my hands on, novels, magazines, newspapers, cereal boxes. I get involved in books to the point where it becomes embarrassing. When I read The Secret Garden, I began to sound quite snotty. When I read The Color Purple, I developed a southern drawl. I’m not safe around books.

Sometimes I spend time studying, not to pull off high marks, which I get whether I study or not, but because I like knowing things. Knowing things will allow me to survive when I start my life. That and money.

Mrs. K. was never what you’d call a robust woman, up and down with one ailment or another over most of those two years. “Do you think you could come straight home after school?” she’d say with her voice one notch away from a whine. “I couldn’t get up the steam to start hoovering the rugs at all yesterday, and they’re just thick.” Or she’d say, “Don’t make any plans for Saturday, I’ve a list for you a mile long. It just gives me the pip thinking about it.” She’d sit there casting her gloomy eye on me, rubbing her belly. And then she’d ease out these long and mournful belches. “Now stay within earshot, Sara,” she used to say. “You never know when I might need something from the drug store.”

But big deal, so what? Being bogged down with household chores didn’t kill me. I got kind of used to running errands and carrying bowls of pale soup and plates of dry toast to her. I’m not complaining. I didn’t exactly feel sorry for the old girl. I felt sort of … responsible. Who else did she have? Frail Frank? Anyway, why would I need friends cluttering up my present life? Reality starts at sixteen.

Picture me as something like a little hyphen on a blank screen. A cursor. Unattached to anything before or after. I move along and down, along and down, until finally I get to page sixteen. That’s when the story starts. Me, alone, in a very sturdy, very compact, glass fortress where I can see out but no one can see beyond the surface. Queen of cool. Of course I’ll need a job because I haven’t been able to save much money, but I’m not fussy. Night watchman at the morgue would suit me fine.

My real dream is this: I’m going up north, as far north as I can go and still get a job, some remote outpost where I’ll have my own space unshared by any other human being. I might have a dog. One of those Huskies, intelligent and loyal. I would like to be a pilot who flies supplies into even more remote places.

“I think you’ll like the Huddlestons’,” Ruth said. “There are other kids there. A ready-made family for you.”

No clutter. No noise. No responsibilities.

“Two boys younger than you.”

“O joy divine.” I took off my glove again and pressed my hand against my side of the windshield to broaden my horizons. Nothing to see except angry snowflakes attacking horizontally and disappearing. The road was becoming narrower and more twisted. We were beyond the boonies. Way beyond. “Turn on your headlights,” I said.

“They’re on.”

I’ve never driven a car, but I know I could do it. Ruth, on the other hand, seems to have skipped driver’s ed. She was intent on putting us in the ditch. She kept turning the wheel too far coming out of a skid, which any damn fool knows – But who cares? I didn’t.

Ruth glanced at me a couple of times as if she had something important to say but didn’t know how to start. Finally, she said, “I’m not trying to pressure you, but couldn’t you agree to read one letter from your mother? It’s been over a year now since she contacted us, looking for you. You’re under no obligation to answer it. But maybe you should give her half a chance to prove herself. You’re prejudging her.”

“She prejudged me.”

“Oh, stop. You know as well as I do how many reasons there are for a woman to give up a baby.”

“None of them good, if you happen to be the baby. Ex-baby.”

“You were adopted immediately. You know that.”

“I don’t remember. Anyway, big deal. They died.”

“Sara. They didn’t do it on purpose.”

“I didn’t say they did.”

“Well, you sound so – The fire was a tragic accident. It wasn’t anyone’s fault. No one set out to deprive you, personally, of a home and a family. It was one of those things.”

“I’m not really interested in pursuing this any further.”

Ruth heaved one of her big, dramatic sighs as if she were going to let the subject drop. But no. “I really should confess,” she said, “that your mother knows you are moving to the Ambrose area.”

“How come? Is there some sort of conspiracy against me? Why are you trying to spoil my life?”

“I didn’t do it,” Ruth said. “But I’m afraid the information got leaked out by mistake. We had temporary help for a while – and the woman is persistent. The last time she contacted me she said she intended to ask everyone in the whole county, if necessary, to track down the family who had adopted her daughter.”

“What’s her point?”

“Your well-being, I gather. She wants to see if you’re happy, and to let you know she’s out there. Seems harmless enough.”

I stared into the ranks of snowflakes driving against the windshield and tried to make out a formation, some pattern, but it only made me dizzy. “Wait a minute,” I said. “I’m not adopted. She’s looking for some kid who’s adopted, and that ain’t me.” I smiled. Safe. Anonymous. “Right?”

Ruth glanced at me and we narrowly missed a snowbank. “You might want a mother someday.”

“I’ll be the judge of that. What does this woman look like?” If I was going to be involved in some kind of cloak-and-dagger chase, I needed a running start. Ruth didn’t know, as it turned out, nor did the woman have a picture of me.

I do have one thing, however, which I’ve never told anyone about. The ad.

Sitting beside Ruth, I returned to my dream of being sixteen, of splitting off, separating myself from people. All people. What I want is sole control of Sara Moone, because up to now my life has had no more importance to anyone than a scrap of paper, scribbled on, torn up, thrown away, burned to an ash. I have never had a say in what happens to me. When I was eight, my foster mother at the time became pregnant with twins. She sat me down for a heart-to-heart talk about this. I was so excited about the twin babies we were going to have that I didn’t hear her tell me that she was giving me back to the Children’s Aid. I was grinning away like an idiot, thinking about how I’d get to feed the babies their bottles, and she was saying, “I’m very sorry, I don’t know what else I can do.” And things like that. And I just stood there when it finally sank in, my lips frozen in a wide stretch across my face and my eyes turning into round empty circles. In my next home, my foster mother was ruled unfit and the family fell apart. Then there was another one, and another, until I stopped being able to sort them out. I’ve been plucked up, plunked down, shuffled and re-dealt so many times my mind refuses to remember it all.

However, sixteen is the magic age. That’s when I can legally drop out of school, legally drop out of foster homes … and legally drop off the edge of the world, I guess, for all anyone would care.

“I really care what happens to you, you know,” Ruth said. She looked at me quickly and then back at the road. We were at the top of a long, slow grade lightly dusted with snow. “You could write to me.”

“And say what?”

“Tell me how you feel about things, about what your life is like. You have that computer; you might as well put it to good use.”

“Can’t. I don’t have a printer. Even if I did, it wouldn’t do you any good. I don’t feel anything about anything, so you’d get nothing but blank pages.” Actually I was beginning to feel us going into a slide down this hill. Ruth felt it, too, and hit the brakes. We did a slow-motion, complete spin and drifted off the road nose-first into the ditch.

“Oh, great,” Ruth said.

“Any survivors?” I said.

She tried gunning the engine. The wheels spun uselessly. “What are we going to do? We’re miles from anywhere.” Her purse was on the seat between us. She opened it and started rummaging around. She took out a package of cigarettes and a lighter.

The inside of the car seemed incredibly small all of a sudden. “What are you doing?”

She started lighting her cigarette. “Do you mind?”

The lighter was turned up too high. I could see her face, her eyes questioning mine, wondering if I minded her smoking, but hoping I didn’t because she needed to smoke, and her hair, pale brown, like dried grass, wisping out from under her green knitted hat toward the flame. The way the flame flared up, I don’t know, I guess it made me panic. I may have screamed. I yelled, anyway, because Ruth jumped and her cigarette flipped out from between her fingers. I saw a rain of sparks in front of the flare from the lighter and I – Forget it.

I got out of the car. Smoke inside a car is sickening.

I remember Ruth running after me. The two of us standing in the middle of snowy nowhere shouting at each other. She tried to put her arm around me, but I gave her a shove and then the bus came along. Out of the white screen of blowing snow, headlights. And Ruth sprawled on the road in its path. One instant Ruth was lit up and the next she was in semi-darkness as the bus’s headlights swerved from side to side down that glassy hill with the tortured sound diesel brakes have drowning out everything else. I grabbed her arm and yanked her into the ditch as the bus crunched past and came to a stop a little farther along the road.

***

It’s fairly quiet here, now, at Château Huddleston, except for me clicking away on this machine. Supper was a major ordeal. Food has never been a big item in my life. Here, however, quantity is everything. God knows what the quality is like. I didn’t eat enough of whatever was being served to tell. After they’d all sucked back about forty tons of unidentifiable, gravy-covered, cooked objects, they paused long enough to breathe and looked at my plate, still brimful. “Edith-Ann will like it,” someone said. Whoever that is. Probably some idiot daughter locked in the attic. This would not be entirely out of the question.

The lord of the manor has retired as has his charming wife. The two delightful foster sons have gone beddy-bye in the room next to mine after surgically removing each other’s windpipes, I gather. They were fighting over a jackknife and then one of them started choking and coughing until Ma (can you dig it?) Huddleston put a stop to it. “And no dessert for three days,” she said. I can’t believe this place.

I see I left off when the bus came along. I was interrupted. No such thing as privacy around here.

To go back: It was the Ottawa bus and we got on. Ruth told the driver where we were going and he said that was his next stop. Sitting beside each other in the last two seats on the bus, we didn’t have a whole lot to say. Pressed close to the window, I looked out. The snow had stopped coming down and was just blowing around now. I’d already told Ruth I was sorry. I was, too. I hadn’t meant to shove her under a bus. I’m cool, but I’m no murderer. “I’m sorry, too,” she’d said. “I should have remembered that you don’t like to be touched.”

Elbows tucked into my rib cage, legs tight against the bus heater, I ignored her remark. Through the bus window I watched the clouds part, revealing the moon, a mean little curved blade slung low in the darkening sky. It was following us.

Fifteen minutes later the bus pulled into the Elite Cafe and Bus Terminal on the edge of the town of Ambrose. “You go inside there,” the bus driver said to Ruth as we stepped down out of the bus into the snowy bluster. “They’ll call you a tow truck and you can get a coffee while you wait.” The bus door eased to, then snapped closed, and the bus disappeared into a turmoil of exhaust and snow.

We looked at each other and shrugged. You could hardly see in through the windows, they were so fogged up. Inside, the warmth of the place almost wrapped itself around us with steam coming up from pots of coffee behind the counter and a frazzle-haired waitress filling the cups of a few old geezers sitting on stools gabbing their heads off, their big coats hanging open. Fluorescent lights beat down on them like a sunny day. A couple of tables stood empty under the windows. I slid into a chair beside one and waited for Ruth to ask the waitress about a tow truck.

Everybody stopped talking to listen in. “Where am I phoning from?” Ruth called to the waitress from the pay phone on the wall. “Ee-lite Cafe out on the number seven. He knows where it is.”

“Not a night to be out on the road,” one of the patrons of the Ee-lite Cafe said to no one in particular.

“That skiffle o’ snow on top o’ the glare ice just slicks her down good,” someone else said.

“D’y’ mind the time we froze up after a long thaw and we were froze up so good there wasn’t hardly a toilet’d flush in the entire county? Two year ago now, it was.”

“It wasn’t neither. It was last spring.”

Ruth went back to the counter to get change for another call and they all shut up again.

“Mr. Huddleston?” Ruth was saying into the phone. “Ruth Petrie from the Children’s Aid. I wonder if you could come into the Elite, uh, Ee-lite Cafe to pick up Sara. I’ve put my car in the ditch.” A pause. “Your foster daughter. Sara Moone.”

Meanwhile I was cringing, trying to disappear into the furniture. Obviously I hadn’t been programmed into Mr. Huddleston’s memory. When I looked up all I could see was a row of eyes staring at me from the mirror above the counter. I turned to the window but I couldn’t see out.

“Yes.” Relief in her voice. “Yes, that’s right.”

The software must have kicked in.

After she hung up, Ruth got us both coffee and then she went to the washroom. There was a general buzz of conversation, some of which I caught.

“Bears for punishment, aren’t they.”

“Oh, I don’t know. Hud, he’s got a firm hand there.”

“Missus is a bit soft.”

“A bit soft. Salt o’ the earth, though.”

“Oh, salt o’ the earth, no question. But why they keep takin’ in them kids, I’ll never tell y’.”

“Bears for punishment.”

Recenzii

“…the players are brilliantly etched…the novel is moving and memorable.”

–Publishers Weekly

“The best young reader novel to come out…this year…”

–The Toronto Star

–Publishers Weekly

“The best young reader novel to come out…this year…”

–The Toronto Star