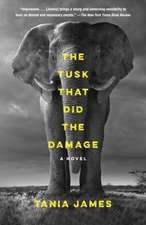

Aerogrammes: And Other Stories

Autor Tania Jamesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 mar 2013

In “Light & Luminous,” a gifted instructor of Indian dance falls victim to the vanity and insecurities that have followed her into middle age. In “The Scriptological Review: A Last Letter from the Editor,” a damaged young man obsessively studies his father’s handwriting in hopes of making sense of his suicide. And in “What to Do with Henry,” a white woman from Ohio takes in the illegitimate child her husband left behind in Sierra Leone, as well as an orphaned chimpanzee who comes to anchor this strange new family. With Aerogrammes, Tania James once again introduces us to a host of delicate, complicated, and beautifully realized characters who find themselves separated from their friends, families, and communities by race, pride, and grief.

Preț: 125.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 188

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.96€ • 25.02$ • 19.79£

23.96€ • 25.02$ • 19.79£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307389022

ISBN-10: 0307389022

Pagini: 180

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307389022

Pagini: 180

Dimensiuni: 134 x 208 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Recenzii

“Tania James’s stories are funny, deeply tender, and each-and-every-one memorable. Aerogrammes is a gift of a collection from a talent who only grows.” —Nathan Englander

“One of the best short story collections I have read in years. . . . funny, tender, and always full of humanity.” —Khaled Hosseini

“By turns rib-shakingly funny and poignant, pinwheeling and wise. . . . Proof that the short story is joyfully, promiscuously, thrillingly alive.” —Karen Russell

“Get ready for a collection of love stories that absolutely doesn’t include a variation on Cinderella-plus-Prince. . . . Every single story contains a . . . minute but luminous event, each a reminder that love entails a lot of wear and tear—but on a good day, lets us transcend the average with a little mystery called tenderness.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“Authentic and deftly drawn.” —The Washington Post

“Tania James is a warmhearted writer. . . . she treats her eclectic band of characters—several children, a chimpanzee, an obsessive analyzer of handwriting, two Indian wrestlers in Edwardian London, a former grocer, an aging dance teacher, a widower, a writer and a ghost—gently, almost parentally, pitying them while recognizing the humor in their predicaments. . . . Her jokes tighten scenes with styptic doses of reality. In these instants we are, as is so often the case, saved from embarrassment by a sense of humor.” —The New York Times Book Review

“James opens a window onto a world marked by loneliness, obsession and wild animals.” —Granta

“Multiculturalism in America. Think Zadie Smith, if Zadie Smith was raised in Kentucky.” —Harper’s Bazaar

“First-rate. . . . James’ prose is clean, deep, limpid; the stories she builds throw strange, beautiful light on completely unexpected places. . . . Always, her descriptions delight.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“These are stories that map out a fresh new world between America and South Asia with a rare blend of humor and sensitivity. Surprising and affecting.” —Romesh Gunesekera

“James’s stories are populated by lively, spectacularly fallible (yet persistently hopeful) characters that toil, mourn, dance, and play—sometimes in rapid succession. . . . To read Aerogrammes is to be transported back to adolescent (or pre-adolescent) days dominated by dance classes, playground politicking, and jumping off (or cowering before) the high dive.” —The Rumpus

“Like all great fiction, James’s stories emerge from a strange and beautiful source of inspiration, then proceed to transcend it.” —Huffington Post

“In her first short story collection, James, whose debut novel Atlas of Unknowns dazzled us, returns with a vengeance, with nine expertly crafted, beautifully set tales that careen from tender to funny to crisp, but always say exactly what they mean.” —Flavorwire

“These feats of emotional range and inventiveness require a precise clarity of vision. . . . Along with James’s compassion and wit, not to mention her crisp, luminous prose, that vision makes the stories in Aerogrammes a delight to read.” —Fiction Writers Review

“While it’s characteristic of writers to have stories to tell, Tania James positively bursts with them. . . . flawless in their execution and always turning our eye toward a new someone and somewhere at precisely the right time” —DBC Reads

“Immaculately crafted . . . brilliantly diverse. . . . James understands the nuances of emotional displacement.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A skilled storyteller. . . . James investigates with compassion and humor the indignities of aging, disability, and alienation at different stages of life. . . . a refreshingly authentic new voice.” —Library Journal

“One of the best short story collections I have read in years. . . . funny, tender, and always full of humanity.” —Khaled Hosseini

“By turns rib-shakingly funny and poignant, pinwheeling and wise. . . . Proof that the short story is joyfully, promiscuously, thrillingly alive.” —Karen Russell

“Get ready for a collection of love stories that absolutely doesn’t include a variation on Cinderella-plus-Prince. . . . Every single story contains a . . . minute but luminous event, each a reminder that love entails a lot of wear and tear—but on a good day, lets us transcend the average with a little mystery called tenderness.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“Authentic and deftly drawn.” —The Washington Post

“Tania James is a warmhearted writer. . . . she treats her eclectic band of characters—several children, a chimpanzee, an obsessive analyzer of handwriting, two Indian wrestlers in Edwardian London, a former grocer, an aging dance teacher, a widower, a writer and a ghost—gently, almost parentally, pitying them while recognizing the humor in their predicaments. . . . Her jokes tighten scenes with styptic doses of reality. In these instants we are, as is so often the case, saved from embarrassment by a sense of humor.” —The New York Times Book Review

“James opens a window onto a world marked by loneliness, obsession and wild animals.” —Granta

“Multiculturalism in America. Think Zadie Smith, if Zadie Smith was raised in Kentucky.” —Harper’s Bazaar

“First-rate. . . . James’ prose is clean, deep, limpid; the stories she builds throw strange, beautiful light on completely unexpected places. . . . Always, her descriptions delight.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“These are stories that map out a fresh new world between America and South Asia with a rare blend of humor and sensitivity. Surprising and affecting.” —Romesh Gunesekera

“James’s stories are populated by lively, spectacularly fallible (yet persistently hopeful) characters that toil, mourn, dance, and play—sometimes in rapid succession. . . . To read Aerogrammes is to be transported back to adolescent (or pre-adolescent) days dominated by dance classes, playground politicking, and jumping off (or cowering before) the high dive.” —The Rumpus

“Like all great fiction, James’s stories emerge from a strange and beautiful source of inspiration, then proceed to transcend it.” —Huffington Post

“In her first short story collection, James, whose debut novel Atlas of Unknowns dazzled us, returns with a vengeance, with nine expertly crafted, beautifully set tales that careen from tender to funny to crisp, but always say exactly what they mean.” —Flavorwire

“These feats of emotional range and inventiveness require a precise clarity of vision. . . . Along with James’s compassion and wit, not to mention her crisp, luminous prose, that vision makes the stories in Aerogrammes a delight to read.” —Fiction Writers Review

“While it’s characteristic of writers to have stories to tell, Tania James positively bursts with them. . . . flawless in their execution and always turning our eye toward a new someone and somewhere at precisely the right time” —DBC Reads

“Immaculately crafted . . . brilliantly diverse. . . . James understands the nuances of emotional displacement.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A skilled storyteller. . . . James investigates with compassion and humor the indignities of aging, disability, and alienation at different stages of life. . . . a refreshingly authentic new voice.” —Library Journal

Notă biografică

Tania James is the author of the novel Atlas of Unknowns. Her fiction has appeared in Boston Review, Granta, One Story, A Public Space, and The Kenyon Review. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Extras

Excerpted from the Hardcover Edition

Excerpt from Lion and Panther in London

•••

The Sensation of the Wrestling World Exclusive Engagement of India’s Catch-as-Catch-Can Champions. Genuine Challengers of the Universe. All Corners. Any Nationality. No One Barred.

GAMA, Champion undefeated wrestler of India, winner of over 200 legitimate matches.

IMAM, his brother, Champion of Lahore.

(These wrestlers are both British subjects.)

£5 will be presented to any competitor, no matter what nationality, whom any member of the team fails to throw in five minutes.

Gama, the Lion of the Punjab, will attempt to throw any three men, without restriction as to weight, in 30 minutes, any night during this engagement, and competitors are asked to present themselves, either publicly or through the management.

no one barred!! all champions cordially invited!! the bigger the better!!

Gama the Great is bored. Imam translates the newspaper notice as best he can while his brother slumps in the wingback chair. On the table between them rests a rose marble chessboard, frozen in play. Raindrops wriggle down the windowpane. It is a mild June in 1910 and their seventh day in London without a single challenge.

Their tour manager, Mr. Benjamin, lured them here from Lahore, promising furious bouts under calcium lights, their names in every newspaper that matters. But the very champions who used to thump their chests and flex their backs for photos are now staying indoors, as if they have ironing to do. Not a word from Benjamin “Doc” Roller or Strangler Lewis, not from the Swede Jon Lemm or the whole fleet of Japanese fresh from Tokyo.

Every year in London, a world champion is crowned anew, one white man after the next, none of whom have wrestled a pehlwan. They know nothing of Handsome Hasan or Kalloo or the giant Kikkar Singh, who once uprooted an acacia tree bare-handed, just because it was blocking the view from his window. Gama has defeated them all, and more, but how is he to be champion of the World if this half of the world is in hiding?

Mr. Benjamin went to great trouble to arrange the trip. He cozied up to the Mishra family and got the Bengali millionaires to finance the cause, printed up press releases, and rented them a small, gray-shingled house removed from the thick of the city, with space enough out back to carry on their training. The house is comfortable enough, if crowded with tables, standing lamps, settees, and armchairs. When it rains, they push the furniture to the walls and conduct their routines in the center of the sitting room.

Other adjustments are not so easy. Gama keeps tumbling out of bed four hours late, his mustache squashed on one side. Imam climbs upon the toilet bowl each morning, his feet on the rim, and engages in a bout with his bowels. Afterward, he inspects the results. If they are coiled like a snake ready to strike, his guru used to say, all is in good shape. There are no snakes in London.

These days, when Mr. Benjamin stops by, he has little more to offer than an elaborate salaam and any issues of Sporting Life and Health & Strength in which they have been mentioned, however briefly. He is baby-faced and bald, normally jovial, but Imam senses something remote about him, withheld, as though the face he gives them is only one of many. “You and your theories,” Gama says.

Left to themselves, Gama and Imam continue to hibernate in the melancholy house. They run three kilometers up and down the road, occasionally coughing in the fume and grumble of a motorcar. They wrestle. They do hundreds of bethaks and dands, lost in the calm that comes of repetition, and at the end of the day, they rest. They bathe. They smooth their skin with dry mustard, which conjures homeward thoughts of plains ablaze with yellow blooms. Sometimes, reluctantly, they play another game of chess.

On the eighth morning, Mr. Benjamin pays a visit. For the first time in their acquaintance, he looks agitated and fidgets with his hat. His handshake is damp. He follows the wrestlers into the sitting room, carrying with him the stink of a recently smoked cigar.

The cook brings milky yogurt and ghee for the wrestlers, tea for Mr. Benjamin. Gama and Imam brought their own cook from Lahore, old Ahmed, who is deaf in one ear but knows every nuance of the pehlwan diet. They were warned about English food: mushy potatoes, dense pies, gloomy puddings—the sort of fare that would render them leaden in body and mind.

When Mr. Benjamin has run out of small talk, he empties a sober sigh into his cup. “Right. Well, I suppose you’re wondering about the tour.”

“Yes, quite,” Imam says, unsure of his words but too anxious to care. It seems a bad sign when Mr. Benjamin sets his cup and saucer aside.

Wrestling in England, Mr. Benjamin explains, has become something of a business. Wrestlers are paid to take a fall once in a while, to pounce and pound and growl on cue, unbeknownst to the audience, which nevertheless seems to enjoy the drama. After the match, the wrestlers and their managers split the money. Occasionally these hoaxes are discovered, to great public outcry, the most recent being the face-off between Yousuf the Terrible Turk and Stanislaus Zbyszko. After Zbyszko’s calculated win, it was revealed that Yousuf the Terrible was actually a Bulgarian named Ivan with debts to pay off.

“And you know of this now only?” Imam asks.

“No—well, not entirely.” Mr. Benjamin pulls on a finger, absently cracks his knuckle. “I thought I could bring you fellows and turn things around. Show everyone what the sport bloody well should be.”

Imam glances at Gama, who is leaning forward, gazing at Mr. Benjamin’s miserable face with empathy.

“There would be challengers”—Mr. Benjamin shrugs—“if only you would agree to take a fall here and there.”

After receiving these words from Imam, Gama pulls back, as if bitten. “Fall how?” Gama says.

“On purpose,” Imam explains quietly.

Gama’s mouth becomes small and solemn. Imam tells Mr. Benjamin that they will have to decline the offer.

“But you came all this way.” Mr. Benjamin gives a flaccid laugh. “Why go back with empty pockets?”

For emphasis, Mr. Benjamin pulls his own lint-ridden pockets inside out and nods at Gama with the sort of encouragement one might show a thick-headed child.

Gama asks Imam why Mr. Benjamin is exposing the lining of his pants.

“The langot we wear, it does not have pockets,” Imam tells Mr. Benjamin, hoping the man might appreciate the poetry of his refusal. Mr. Benjamin blinks at him and explains, in even slower English, what he means by “empty pockets.”

So this is London, Imam thinks, nodding at Mr. Benjamin. A city where athletes are actors, where the ring is a stage.

In a final effort, Mr. Benjamin takes their story to the British press. Health & Strength publishes a piece entitled “Gama’s Hopeless Quest for an Opponent,” while Sporting Life runs his full-length photograph alongside large-lettered text: “GAMA, the great Indian Catch-Can Wrestler, whose Challenges to Meet all the Champions have been Unanswered.” The photographer encouraged Gama to strike a menacing pose, but in the photo, Gama appears flat-footed and blank, his fists feebly raised. “At least you look taller,” Imam says.

Finally, for an undisclosed sum, Doc Roller takes up Gama’s challenge. Mr. Benjamin says that Doc is a fully trained doctor and the busiest wrestler in England, a fortunate combination for him because he complains of cracked ribs after every defeat.

They meet at the Alhambra, a sprawling pavilion of arches and domes, its name studded in bulbs that blaze halos through the fog. Inside, golden foliage and gilded trees climb the walls. Men sit shoulder to shoulder around the roped-off ring, and behind them, more men in straw boaters and caps, standing on bleachers, making their assessments of Gama the Great, the dusky bulk of his chest, the sculpted sandstone of each thigh. Imam sits ringside next to Mr. Benjamin, in a marigold robe and turban. He is a vivid blotch in a sea of grumpy grays and browns. He feels slightly overdressed.

Gama warms his muscles by doing bethaks. He glances up but keeps squatting when Roller swings his long legs over the ropes, dauntingly tall, and whips off his white satin robe to reveal wrestling pants, his abdominal muscles like bricks stacked above the waistband.

They take turns on the scale. Doc is a full head taller and exceeds Gama by thirty-four pounds. Following the announcement of their weights, the emcee bellows, “No money in the world would ever buy the Great Gama for a fixed match!” To this, a joyful whooping from the audience.

Imam absently pinches the silk of his brother’s robe, which is draped across his lap. Every time he watches his brother in a match, a familiar disquiet spreads through his stomach, much like the first time he witnessed Gama in competition.

Imam was eight, Gama twelve, when their uncle brought them to Jodhpur for the national strong-man competition. Raja Jaswant Singh had gathered hundreds of men from all across India to see who could last the longest drilling bethaks. The competitors took their places on the square field of earth within the palace courtyard, and twelve turbaned royal guards stood sentinel around the grounds, their tall gold spears glinting in the sun. Spectators formed a border some meters away from the field, and when little Gama emerged from their ranks and joined the strong men, laughter trailed behind him. Gama was short for his age but hale and sturdy even then.

Excerpt from Lion and Panther in London

•••

The Sensation of the Wrestling World Exclusive Engagement of India’s Catch-as-Catch-Can Champions. Genuine Challengers of the Universe. All Corners. Any Nationality. No One Barred.

GAMA, Champion undefeated wrestler of India, winner of over 200 legitimate matches.

IMAM, his brother, Champion of Lahore.

(These wrestlers are both British subjects.)

£5 will be presented to any competitor, no matter what nationality, whom any member of the team fails to throw in five minutes.

Gama, the Lion of the Punjab, will attempt to throw any three men, without restriction as to weight, in 30 minutes, any night during this engagement, and competitors are asked to present themselves, either publicly or through the management.

no one barred!! all champions cordially invited!! the bigger the better!!

Gama the Great is bored. Imam translates the newspaper notice as best he can while his brother slumps in the wingback chair. On the table between them rests a rose marble chessboard, frozen in play. Raindrops wriggle down the windowpane. It is a mild June in 1910 and their seventh day in London without a single challenge.

Their tour manager, Mr. Benjamin, lured them here from Lahore, promising furious bouts under calcium lights, their names in every newspaper that matters. But the very champions who used to thump their chests and flex their backs for photos are now staying indoors, as if they have ironing to do. Not a word from Benjamin “Doc” Roller or Strangler Lewis, not from the Swede Jon Lemm or the whole fleet of Japanese fresh from Tokyo.

Every year in London, a world champion is crowned anew, one white man after the next, none of whom have wrestled a pehlwan. They know nothing of Handsome Hasan or Kalloo or the giant Kikkar Singh, who once uprooted an acacia tree bare-handed, just because it was blocking the view from his window. Gama has defeated them all, and more, but how is he to be champion of the World if this half of the world is in hiding?

Mr. Benjamin went to great trouble to arrange the trip. He cozied up to the Mishra family and got the Bengali millionaires to finance the cause, printed up press releases, and rented them a small, gray-shingled house removed from the thick of the city, with space enough out back to carry on their training. The house is comfortable enough, if crowded with tables, standing lamps, settees, and armchairs. When it rains, they push the furniture to the walls and conduct their routines in the center of the sitting room.

Other adjustments are not so easy. Gama keeps tumbling out of bed four hours late, his mustache squashed on one side. Imam climbs upon the toilet bowl each morning, his feet on the rim, and engages in a bout with his bowels. Afterward, he inspects the results. If they are coiled like a snake ready to strike, his guru used to say, all is in good shape. There are no snakes in London.

These days, when Mr. Benjamin stops by, he has little more to offer than an elaborate salaam and any issues of Sporting Life and Health & Strength in which they have been mentioned, however briefly. He is baby-faced and bald, normally jovial, but Imam senses something remote about him, withheld, as though the face he gives them is only one of many. “You and your theories,” Gama says.

Left to themselves, Gama and Imam continue to hibernate in the melancholy house. They run three kilometers up and down the road, occasionally coughing in the fume and grumble of a motorcar. They wrestle. They do hundreds of bethaks and dands, lost in the calm that comes of repetition, and at the end of the day, they rest. They bathe. They smooth their skin with dry mustard, which conjures homeward thoughts of plains ablaze with yellow blooms. Sometimes, reluctantly, they play another game of chess.

On the eighth morning, Mr. Benjamin pays a visit. For the first time in their acquaintance, he looks agitated and fidgets with his hat. His handshake is damp. He follows the wrestlers into the sitting room, carrying with him the stink of a recently smoked cigar.

The cook brings milky yogurt and ghee for the wrestlers, tea for Mr. Benjamin. Gama and Imam brought their own cook from Lahore, old Ahmed, who is deaf in one ear but knows every nuance of the pehlwan diet. They were warned about English food: mushy potatoes, dense pies, gloomy puddings—the sort of fare that would render them leaden in body and mind.

When Mr. Benjamin has run out of small talk, he empties a sober sigh into his cup. “Right. Well, I suppose you’re wondering about the tour.”

“Yes, quite,” Imam says, unsure of his words but too anxious to care. It seems a bad sign when Mr. Benjamin sets his cup and saucer aside.

Wrestling in England, Mr. Benjamin explains, has become something of a business. Wrestlers are paid to take a fall once in a while, to pounce and pound and growl on cue, unbeknownst to the audience, which nevertheless seems to enjoy the drama. After the match, the wrestlers and their managers split the money. Occasionally these hoaxes are discovered, to great public outcry, the most recent being the face-off between Yousuf the Terrible Turk and Stanislaus Zbyszko. After Zbyszko’s calculated win, it was revealed that Yousuf the Terrible was actually a Bulgarian named Ivan with debts to pay off.

“And you know of this now only?” Imam asks.

“No—well, not entirely.” Mr. Benjamin pulls on a finger, absently cracks his knuckle. “I thought I could bring you fellows and turn things around. Show everyone what the sport bloody well should be.”

Imam glances at Gama, who is leaning forward, gazing at Mr. Benjamin’s miserable face with empathy.

“There would be challengers”—Mr. Benjamin shrugs—“if only you would agree to take a fall here and there.”

After receiving these words from Imam, Gama pulls back, as if bitten. “Fall how?” Gama says.

“On purpose,” Imam explains quietly.

Gama’s mouth becomes small and solemn. Imam tells Mr. Benjamin that they will have to decline the offer.

“But you came all this way.” Mr. Benjamin gives a flaccid laugh. “Why go back with empty pockets?”

For emphasis, Mr. Benjamin pulls his own lint-ridden pockets inside out and nods at Gama with the sort of encouragement one might show a thick-headed child.

Gama asks Imam why Mr. Benjamin is exposing the lining of his pants.

“The langot we wear, it does not have pockets,” Imam tells Mr. Benjamin, hoping the man might appreciate the poetry of his refusal. Mr. Benjamin blinks at him and explains, in even slower English, what he means by “empty pockets.”

So this is London, Imam thinks, nodding at Mr. Benjamin. A city where athletes are actors, where the ring is a stage.

In a final effort, Mr. Benjamin takes their story to the British press. Health & Strength publishes a piece entitled “Gama’s Hopeless Quest for an Opponent,” while Sporting Life runs his full-length photograph alongside large-lettered text: “GAMA, the great Indian Catch-Can Wrestler, whose Challenges to Meet all the Champions have been Unanswered.” The photographer encouraged Gama to strike a menacing pose, but in the photo, Gama appears flat-footed and blank, his fists feebly raised. “At least you look taller,” Imam says.

Finally, for an undisclosed sum, Doc Roller takes up Gama’s challenge. Mr. Benjamin says that Doc is a fully trained doctor and the busiest wrestler in England, a fortunate combination for him because he complains of cracked ribs after every defeat.

They meet at the Alhambra, a sprawling pavilion of arches and domes, its name studded in bulbs that blaze halos through the fog. Inside, golden foliage and gilded trees climb the walls. Men sit shoulder to shoulder around the roped-off ring, and behind them, more men in straw boaters and caps, standing on bleachers, making their assessments of Gama the Great, the dusky bulk of his chest, the sculpted sandstone of each thigh. Imam sits ringside next to Mr. Benjamin, in a marigold robe and turban. He is a vivid blotch in a sea of grumpy grays and browns. He feels slightly overdressed.

Gama warms his muscles by doing bethaks. He glances up but keeps squatting when Roller swings his long legs over the ropes, dauntingly tall, and whips off his white satin robe to reveal wrestling pants, his abdominal muscles like bricks stacked above the waistband.

They take turns on the scale. Doc is a full head taller and exceeds Gama by thirty-four pounds. Following the announcement of their weights, the emcee bellows, “No money in the world would ever buy the Great Gama for a fixed match!” To this, a joyful whooping from the audience.

Imam absently pinches the silk of his brother’s robe, which is draped across his lap. Every time he watches his brother in a match, a familiar disquiet spreads through his stomach, much like the first time he witnessed Gama in competition.

Imam was eight, Gama twelve, when their uncle brought them to Jodhpur for the national strong-man competition. Raja Jaswant Singh had gathered hundreds of men from all across India to see who could last the longest drilling bethaks. The competitors took their places on the square field of earth within the palace courtyard, and twelve turbaned royal guards stood sentinel around the grounds, their tall gold spears glinting in the sun. Spectators formed a border some meters away from the field, and when little Gama emerged from their ranks and joined the strong men, laughter trailed behind him. Gama was short for his age but hale and sturdy even then.