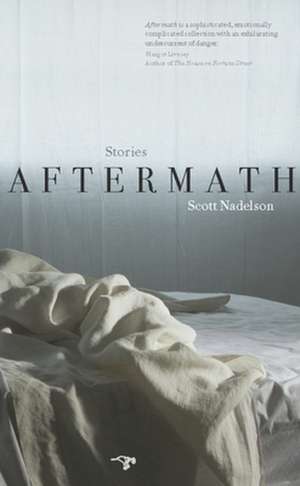

Aftermath: Stories

Autor Scott Nadelsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2011

Preț: 114.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.98€ • 22.70$ • 18.29£

21.98€ • 22.70$ • 18.29£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780979018862

ISBN-10: 0979018862

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 140 x 226 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: HAWTHORNE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0979018862

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 140 x 226 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: HAWTHORNE BOOKS

Cuprins

15 Dolph Schayes’s Broken Arm

27 Oslo

45 Aftermath

97 The Old Uniform

131 If You Needed Me

161 Backfill

187 Saab

207 West End

Recenzii

WHETHER HE'S DESCRIBING a married couple experimenting with trial

separation or a young woman dealing with her father's cancer, Scott

Nadelson writes brilliantly about the many forms of ambivalence that

love can take. His characters, of all ages, are wonderfully vivid.

Aftermath is a sophisticated, emotionally complicated collection with

an exhilarating undercurrent of danger. —MARGOT LIVESEY, author of The House on Fortune Street

SCOTT NADELSON'S STORIES begin with some rupture--a break-up, an accident--and explore the messy results. The relative (and often self-imposed) hell in which Nadelson's characters find themselves is more than counter-balanced by the heaven of the telling. There's so much to enjoy in the bluesy aftermath: the deftly drawn characters, the world replete with all-too-normal strangeness, and the sharp-eyed, clever perceptions. I emerged from the book, as if from a movie, so lost in and convinced by the vivid screen, that the world felt a little sun-bleached in comparison. —DEBRA SPARK, author of Good for the Jews

Extras

Oslo

Scott Nadelson

From Aftermath: Stories

Add Aftermath: Stor… to your shopping bag.

Oslo

Jerusalem—August, 1995

The orange soda was too gassy for Joel to gulp. He’d wanted orange juice but had made the mistake of letting his grandfather order for him. His grandmother had made the same mistake, and now the waitress brought out coffee in tiny ceramic cups. His grandfather took one sip, said, “Awful,” and pushed the entire saucer away.

His grandmother winced but managed to swallow. “It’s Turkish,” she said. “If we want regular, I think we have to order ‘filtered.’”

“Awful,” his grandfather repeated. His white hair stuck up an inch from his scalp all around, so thick it was hard to see how a brush could make its way through. His skin seemed thick, too, but darker and leathery from the Florida sun, the wrinkles circling his eyes like cracks in a punctured windshield. Joel knew something about windshield cracks, having shot a BB at his mother’s boyfriend’s Mustang a week before they’d left on this trip. His grandfather wore a white golf shirt, white linen slacks, white socks and tennis shoes, and in his back pocket was a white cloth hat he’d put on when he started to overheat. He flipped through the guidebook he hadn’t let go of once in the last two days, holding it at arm’s length to read. “The tour starts at ten-thirty.”

“You told us already,” Joel said. “You told us yesterday.”

“Why don’t you put your glasses on,” his grandmother said. “You’ll strain your eyes.”

“We should get going,” his grandfather said.

“We’ve got half an hour,” his grandmother said.

“We’re always early,” Joel said.

His grandmother lifted her cup to her lips, balancing it between both thumbs and forefingers. “I’d like to finish my coffee. It’s lovely once you get used to the grit.”

The café was on Ben Yehuda Street, their table so far out into the pedestrian lane that twice now, a passing tourist had bumped Joel’s arm. “Good for people watching,” his grandmother had said, but Joel watched only his fingers in the mesh of the wrought iron table top, his pinkie able to wriggle through one of the holes. He was thirteen, three months past his bar mitzvah, a sunken-chested boy with long twig arms that suggested he might, one day, grow taller than his grandfather, who claimed to be five-foot-nine but couldn’t have been more than five-seven, Joel was sure. Joel’s father was five-nine, but since Joel hadn’t seen him since his bar mitzvah reception three months ago, it was hard to remember exactly how tall that looked. His mother’s boyfriend was six-three, too tall for his mother, Joel thought. Too loud for his mother, too, with a booming voice that bubbled up from his round belly. His mother had been going out with Dennis for nearly a year now, her soft words drowned out by Dennis’s constant yammering, his snorting laugh. Dennis knew something about everything and didn’t let anyone else talk, ever. You could say, “I ate a yeti for lunch today,” and Dennis would twist the end of his mustache and answer, “Funny story about yetis. When I was backpacking through Nepal and Pakistan—” And then he’d be off, talking for an hour straight about climbing to base camp at K2, about how he thought his ear was frostbitten and ready to fall off, about his friend who went snowblind and nearly dropped into a crevasse, but not another word about yetis.

It was impossible not to hate him, and all summer Joel had tried to make Dennis hate him back. He’d hidden his wallet for a whole week, returning it only when Dennis said, “Look, pal, I’m about to run out of gas. You let me have my Visa, I’ll buy you a guitar. I started playing when I was about your age. First guitar I had was a beat-up Les Paul—” Then he was off again, talking about his band, the time he’d gotten thrown off the stage at the Fillmore, and to shut him up, Joel brought him his wallet. Later, he let the air out of all the Mustang’s tires. After his mother lectured him for half an hour, Joel shook Dennis’s hand and muttered an apology. “A truce, huh?” Dennis said. “Just like Grant and Lee at Appomattox. ‘The Gentlemen’s Agreement.’ Most people think that was the end of the war, but it wasn’t. Did you know the last Confederate general to surrender was the Cherokee Stand White—”

Truces were made to be broken, though he knew the BB had been going too far. He’d borrowed the gun from a neighbor kid and then swore he’d had nothing to do with the hole in the windshield. His mother had promised to punish him as soon as she had enough evidence. It was only a matter of time before she found out where he’d gotten the gun, one of the few things that made him thankful to be spending the next three weeks halfway around the world. The windshield would be fixed by the time he got home, the whole thing, with luck, forgotten.

This trip was his bar mitzvah present from his grandparents, though he’d asked for a computer or cash. His grandmother had kept it secret until after the reception, when only a few family members were left at his mother’s house. Joel had already been in a lousy mood by then, because his father had just left, on his way back to Seattle, where he sold medical equipment and lived in a converted warehouse. Joel hadn’t been out to see him yet, and could only imagine him walking around in an open, echoing space, cardboard boxes stacked in one corner, a forklift in another. Before he drove to the airport, his father had clapped him on the back and said, “Way to go, kiddo. You really nailed that haftarah.” But Dennis had been close by, and though he wasn’t even Jewish, started talking about the origins of the Kabbalah. Joel wanted to pull his father away, talk to him in private, ask him about the warehouse and when he might visit, but his father seemed interested in what Dennis was saying, nodding often and encouraging him with a mumbled, “Is that so?” and “I had no idea.” Didn’t he know better than to humor the guy? Didn’t he want to knock him on his ass for the nerve of dating his ex-wife? Soon his father checked his watch and said, “I’d love to hear more, but it’ll have to wait till next time. Come give me a hug, JoJo. Have fun opening your presents.”

Then his grandmother came to him with an envelope, smiling in a tense, close-lipped way that tried to hide her excitement but couldn’t. She looked much younger than his grandfather, partly because she dyed her hair a reddish brown and kept it up in a wispy sort of perm, partly because her skin, though slack over cheeks and chin, was the softest he’d ever felt. When she kissed him he smelled baby oil. The envelope wasn’t heavy, which meant most likely there was a check inside, not cash. A check would go straight into his bank account, not to be seen again until college, but he’d already pocketed three hundred-dollar bills his Uncle Ron, a dentist, had slipped him on the sly. But now, instead of a check, he pulled out a plane ticket. Seattle, he thought, and got ready to hug his grandmother. But then he saw the airline: El Al. “We leave on August first!” his grandmother squealed, and his grandfather said to people around him, “It nearly killed the woman to keep a secret this long. It’s all I’ve heard about for six months.” Joel missed his father already and wanted to cry, but his grandmother was smiling so brightly, the relatives saying what a wonderful gift it was, especially now with all the recent developments, peace finally within reach, that he did hug her and said thanks to his grandfather, who took the ticket from him, saying he’d keep it safe until they left. “The thing about Israel,” Dennis said. “It’s not just the history that’s complicated, or the politics, but the people who live there—”

And that’s when Joel had had it, heading up to his room, leaving the rest of his presents for another day.

Now he finished his orange soda and tried to belch, but the gas just rattled around his chest and leaked out silently. His grandmother smiled at him, black grounds caught between her front teeth, top and bottom. It was still morning and already too hot, hotter even than Fort Lauderdale, where his grandparents lived between a golf course and a pond shared by exotic birds and an alligator. Already his grandfather had the scowling, impatient look that for the past three days hadn’t shown up until afternoon. All around them were air-conditioned buildings, but here they were, sitting under the broiling sun like morons. Across the street was McDavid’s, a name Joel found less funny than curious, wondering what the Jewish version of the Big Mac would taste like, whether there was a Ronald McDavid with a beard and sidelocks. Twice so far he’d asked if they could eat there, but his grandfather said fast food would clog your arteries whether it was kosher or not.

Joel had never thought much about coming to Israel, though his Hebrew school teacher, Mrs. Nachman, had talked about it constantly, closing her eyes and saying wistfully, “Next year in Jerusalem,” even when it was six months until Passover. The walls of her classrooms were covered in maps made between 1967 and 1978, none with the Green Line printed in, just a solid mass from the Golan to Sinai. “If we give up land for peace, the six million die in vain,” she told the class. “When the next Holocaust comes, you’ll be glad there’s enough room for all of us.” Another time she said, “The Arabs, they breed like vermin. That’s why you have to have as many children as you can.” She called Rabin a traitor, Clinton a fool, Arafat the spawn of demons. Joel didn’t question what she said, didn’t care one way or another, until she started talking about intermarriage. “If you want to get divorced, go ahead, marry a gentile. If you want to destroy three thousand years of history. If you want to spit on the graves of the six million.” The Jewish girls Joel knew were all flat-chested and loudmouthed, and he had no intention of marrying any of them. At his bar mitzvah he’d danced with three girls from his middle school, all blonde, all Christian, all giggling at the blessings over the wine and bread. Afterward, Dennis said, “You’ve got an eye for the shiksas, huh, pal? You know about Portnoy’s complaint?” Before he could go on, Joel said, “I’m not complaining,” and all the adults around him laughed.

He knew he should be grateful to his grandparents for bringing him here, knew he should feel a connection to the land Mrs. Nachman called his birthright. But all they did was take tours of one part of the city or another, and it was like being around Dennis for hours on end, getting piled with dates and details when all he wanted was to let his head be empty for a change. It was a hundred degrees and he had to wear long pants everywhere or else get turned away from the churches and synagogues and mosques. They had three weeks of tours planned, to the Galilee, to the Negev, to the Mediterranean coast, and he thought he’d go crazy. The only place he wanted to go was the Dead Sea, to find out if he really could float because of all the salt, but that trip wasn’t planned until their last week, and by then he’d just want to stay at the hotel, floating in the pool.

All he liked so far were the shops, the ones here on Ben Yehuda Street with silver

Notă biografică

Descriere

THE CHARACTERS IN SCOTT NADELSON’S third collection are living in the wake of momentous events-- the rupture of relationships, the loss of loved ones, the dissolution of dreams, and yet they find new ways of forging on with their lives, making accommodations that are sometimes delusional, sometimes destructive, sometimes even healthy. In “Oslo,” a thirteen-year-old boy on a trip to Israel with his grandparents grapples with his father’s abandonment and his own rocky coming-of-age. In “The Old Uniform,” a young man left by his fiancée revisits the haunts of his single days, and on a drunken march through nighttime Brooklyn, begins to shed the false selves that have kept him from fully living. And in the title story, a couple testing out the waters of trial separation quickly discover how deeply the fault lines of their marriage run and how desperately they want to hang onto what remains. Mining Nadelson’s familiar territory of Jewish suburban New Jersey, these fearless, funny, and quietly moving stories explore the treacherous crossroads where disappointments meet unfulfilled desire.