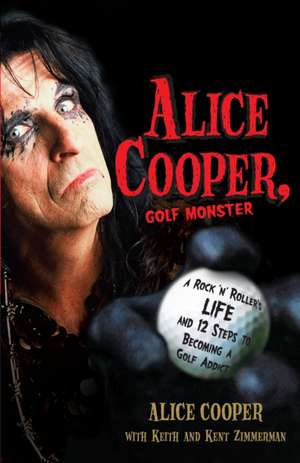

Alice Cooper, Golf Monster: A Rock 'n' Roller's Life and 12 Steps to Becoming a Golf Addict

Autor Alice Cooper Keith Zimmerman, Kent Zimmermanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2008

In this tell-all memoir, Alice Cooper speaks candidly about his life and career, including all the years of rock ’n’ roll history he’s been a part of, the addictions he faced, and the surprising ways he found redemption.

From a childhood spent as a minister’s son worshiping baseball and rock ’n’ roll; to days on the road with his band, working to make a name for themselves; to stardom and the insanity that came with it, including a quart-of-whiskey-a-day habit; to drying out at a sanitarium back in the late ’70s, Alice Cooper paints a rich and rockin’ portrait of his life and his battle against addiction—fought by getting up daily at 7 a.m. to play 36 holes of golf.

Alice tells hilarious, touching, and sometimes astounding stories about Led Zeppelin and the Doors, George Burns and Groucho Marx, John Daly and Tiger Woods . . . everyone is here from Dalí to Elvis to Arnold Palmer.

Alice Cooper, Golf Monster is the incredible story of someone who rose through the rock ’n’ roll ranks releasing platinum albums and selling out arenas with his legendary act—all while becoming one of the best celebrity golfers around.

Preț: 85.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 128

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.37€ • 17.09$ • 13.55£

16.37€ • 17.09$ • 13.55£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307382917

ISBN-10: 0307382915

Pagini: 260

Ilustrații: 50 B&W PHOTOS; 18 4-C PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 131 x 205 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307382915

Pagini: 260

Ilustrații: 50 B&W PHOTOS; 18 4-C PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 131 x 205 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Alice Cooper is a legendary rock icon, his name a household word. He tours around the world every year and continues to release albums. He also participates in many celebrity charity events and has hosted ten of his own annual Alice Cooper Celebrity Golf Tournaments. He is a comfortable five handicap.

Keith and Kent Zimmerman are a unique writing team of twin brothers. They are the coauthors of twelve books, including Rotten with John Lydon of the Sex Pistols, Orange County Choppers™: The Tale of the Teutuls, and the New York Times bestseller Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club.

From the Hardcover edition.

Keith and Kent Zimmerman are a unique writing team of twin brothers. They are the coauthors of twelve books, including Rotten with John Lydon of the Sex Pistols, Orange County Choppers™: The Tale of the Teutuls, and the New York Times bestseller Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

The Fabulous Furniers

I was born Vincent Damon Furnier, named after one of my uncles and Damon Runyon. From the age of ten, I grew up in a religious home; my grandfather was an evangelist and my parents joined his church too. Before then, though, we lived in East Detroit and worshiped baseball. I was the happiest kid in the world.

The Furniers were Huguenots, part French-Canadian people who came over to the New World with the French Protestants in the seventeenth century. They eventually married into some Sioux Indians and a lot of Irish. As a result, two out of three parts of my ethnic background are very alcohol prone. My seventh cousin was the Marquis de Lafayette, the same Lafayette who secured the support of the French during the American Revolution and fought alongside George Washington at Valley Forge. Look at a portrait of Lafayette and you’ll notice the same high cheekbones and long black hair as me. Some say I look just like him, especially when I’m on stage with my sword. I can feel my bloodlines, since swashbuckling comes naturally to me—that’s the French part of me, I guess.

My grandfather, Thurman Sylvester Furnier, was the president of what was called the Church of Jesus Christ. It wasn’t the Church of Latter- day Saints—it wasn’t a Mormon church. In fact, their biggest religious rivals were the Mormons. If you called one of his church members a Mormon, that was like stabbing them in the heart.

My mother was born Ella McCartt in Glenmary, Tennessee. You can’t find Glenmary on a map. It was a whistle-stop. Her mother died when she was very young. She has childhood memories of putting clear liquid into Ball jars for her dad, who was a moonshiner in Glenmary. She had six brothers and sisters, and all of them helped out with the “family business”—and meanwhile the old man kept about forty or fifty thousand dollars in cash buried in the yard. This was in 1946, and at that time, fifty grand was equivalent to about half a million dollars. My grandfather didn’t trust banks.

At age sixteen, around the end of World War II, my mother ran away from home and found her way up to Detroit to work in the factories. That’s where she met my dad, whom people called Mick, though his real name was Ether Maroni Furnier (another Mormon-sounding name). He had just been discharged from the Navy. They were soon married.

I was born in Detroit on February 4, 1948. My first memory of growing up in working-class East Detroit is sitting in a smoke-filled living room with my dad and his brothers, watching Friday-night boxing. There was lots of Carling’s Black Label beer and Lucky Strike cigarettes; I would drink Vernor’s ginger ale. There was always so much smoke in the room, I’m surprised I didn’t contract lung cancer. All the girls stayed in the other room while I sat with the men, my uncles and their buddies, watching the fights on a tiny black-and- white TV set.

Growing up in Detroit was great. I loved my life because my dad and my uncles were so cool. I was the only boy in our family. There was me (Vince) and my sister Nickie, then thirteen cousins, mostly girls. I was the only male left to carry on the Furnier name. So, of course, I ended up legally changing my name to Alice Cooper.

My uncles were Damon Runyon–type characters—tough guys with colorful speech and fascinating stories. Uncle Jocko ran a crooked pool hall in East Detroit. He was my dad’s oldest brother, a spry lightweight prizefighter with a broken nose and not an ounce of fat on him. We all called him Jocko, but his real name was Vincent Collier Furnier. I was named after him. If you wanted to buy anything hot, you went to Jocko’s pool hall. Or if Fast Eddie Felson came in to play Minnesota Fats, that happened at Jocko’s too. It was a famous Detroit dump. During a hot game, the doors would close and lock for hours, sometimes days. My uncle would bring in food and drinks and host the game in exchange for a small cut of the winnings.

Jocko was a swell guy. He used to come over and poke me in the ribs, saying, “Watch that right hook!”

My uncle Lefty, whose real name was Lonson Thurman Furnier, was a whole different deal. He was what you would refer to as a playboy. I never saw Uncle Lefty without a tuxedo, his shirt half-buttoned. He had left Detroit and moved west to Los Angeles, and he worked for Jet Propulsion Labs there. He was the guy who wined and dined the company’s biggest accounts, which is why he was always dressed to the nines. He was part James Bond, part wheeler-dealer—a total Rat Pack– type guy. He would have fit in well with Sinatra and Martin. In fact, he actually hung out with Lana Turner and Ava Gardner, some of the same girls the Rat Pack dated (without my aunt knowing about it, of course).

The great industrial car town of Detroit has always been your classic sports city. The Red Wings were unbeatable. The Pistons were great. Even the Detroit Lions were a really good team at one time. But the Tigers were a religion in our household. They had Ty Cobb, the greatest player of all time, on their team, plus Al Kaline, Mickey Cochrane, Hank Greenberg, and Denny McLain. These were legendary players playing on mythical teams. It was all my dad and I talked about: “What did the Tigers do last night?” I was transfixed with Ernie Harwell’s colorful play-by-play commentary on the radio.

I lived for baseball. When the sun came up, I grabbed my glove and I was ready to play until the sun went down, when you couldn’t see the ball anymore and it was time to rush home for dinner.

East Detroit was a real American melting pot. Each street had their crew—not so much gangs, but characters who banded together as teams. One street over might be all-Italian, while the street after that could be all-black. And next to the blacks were the Irish. Lincoln Street, where I grew up, was principally Polish. People’s names ended in “ski.” Kowalski, Jankowski, Adamski . . . Furnier. We were practically the only non-Polish family on Lincoln. So we were the Polish team. Mornings during baseball season, someone would invariably ask, “Who are we playing today?”

“We’re playing the Irish.”

So we’d walk over to Corktown, the old Irish district. The Irish were cool enough guys. The next day, we’d play the Italians. Hopefully, Bruno wasn’t pitching, because that guy threw hard. We all knew each other, and there weren’t any ethnic or racial problems. Every day a different team, every day a different ethnic nationality. Sandlot rules. No grass. A brand-new baseball was just unheard of. Our baseball had a great big flap coming out of it until it was eventually taped up. Then we batted around a ball wrapped tight in black electrician’s tape. We did whatever we could do, just to play.

I went on to become a pretty good baseball player. One of my best skills was hand-to-eye coordination. I could put the bat on the ball inside or outside the strike zone. If somebody threw a pitch two feet out of the strike zone, low and outside, I could put my bat out and hit it. And I had good rhythm.

My room was a shrine to the Detroit Tigers. No posters, just pictures. A dozen shoe boxes stuffed with baseball cards, cards from packages bought for a nickel apiece, that came with flat squares of bubble gum that congealed into one giant gum brick. I’m sure I had a Mickey Mantle rookie card stashed in there somewhere, along with other cards that could have been worth hundreds or thousands of dollars today if my mother hadn’t thrown them out after I left home. That’s where my allowance went. We traded our cards and flipped doubles. Played tops. When I wasn’t playing baseball or trading cards, I was lying on my bed in my room memorizing batting averages and ERAs. Music wasn’t such a big deal to me. Elvis was out there, and yeah he was cool, but I was addicted to baseball.

On my seventh birthday, my dad got us tickets to a Tigers game at Briggs Stadium. It would be the first time I had seen my heroes play in person. With the game still two months away, I couldn’t sleep. I was a basket case. I was going to see Al Kaline, Harvey Kuenn, Charlie Maxwell, Rocky Colavito, and Jim Bunning.

I remember it distinctly. It was the Tigers vs. the Cleveland Indians, a doubleheader. I remember walking up the ramp of Briggs Stadium and the smell of freshly mowed grass and hot dogs. I remember hearing the cracking sound of batting practice, the sock of a baseball soaring into the outfield. I sat there dumbfounded throughout both games, not moving. I didn’t want a Coke. I didn’t want a hot dog. I didn’t ask for anything. I was afraid if I moved, it was all going to be over. Jim Bunning vs. Herb Score. Charlie Maxwell hit four home runs in two games. We won 7–0 and 8–2 and swept the doubleheader. I went home that night exhausted but in heaven. It was the best day I could ever have imagined. If someone had offered me a choice, Disneyland or a Tigers doubleheader, it would have been a no-brainer: Tigers all the way. To this day, when ESPN flashes MLB scores, I still check to see whether the Tigers won or lost. The Tigers run deep in my psyche.

In our family, there were three basic rules:

1. You had to be a Democrat.

2. You had to pull for the Tigers and the Michigan Wolverines.

3. You had to be American League.

The All-American Detroit family. If you strayed outside any of those rules, it was “What’s wrong with that kid of yours?” While Catholicism was very common and a lot of my friends were Catholic, we didn’t fuss over who was Catholic or who was Protestant. Nobody cared. The black and white thing didn’t exist in my home, nor did we see any difference between the Italians and the Irish. Honestly, if a black guy played baseball, especially if he was a shortstop (a rare commodity), or if he could hit, we simply didn’t see color. The only question was, Is he a power hitter, a singles hitter, or a strikeout pitcher? Was he a good basketball player? Sports was the measuring stick of a person’s worth during my childhood.

Music and sports never mixed back in the neighborhood. Only later did we find out that Rod Stewart could have been a pro soccer player, or that Elton John was a great tennis player. Just recently, in Britain, they listed the top rock-star athletes. For instance, Bruce Dickinson, the lead singer of Iron Maiden, is a highly ranked fencing champion. (I was the only American in their top ten, and rated number two as the golfer on the list.)

And nobody played a game like golf when I was a kid in Detroit. Nobody played tennis, either. A sport in Detroit was considered any activity where you hit somebody or knocked them down. Only five sports existed in our world: baseball, football, hockey, basketball . . . and grand-theft auto. Golf and tennis weren’t even considered sports. They ranked right down there with badminton or girls’ field hockey. Bowling was big, but it wasn’t considered a sport as much as just an excuse to drink on a Saturday night.

Over the years, my dad did many things for a living, things like driving a cab and selling used cars. At the car lot, he worked for a couple of nefarious characters and unfortunately my dad couldn’t sell a used car to save his life! He wasn’t corrupt enough. My dad would be almost through a sale, and just as the poor sucker would be driving away, he would run out across the lot and yell out, “Stop! We turned the odometer back and the whole left side of the car is Bondo!” His bosses would warn him that he had to get out of the business. He was just too honest.

My dad worked strictly on commission, so if he sold a car for $300, he only got about thirty bucks, maximum. I remember going to work with my dad. He would put all his spare change in a cup on top of the icebox, and whatever was in the change cup was our lunch money. If there wasn’t much, then lunch might be just a candy bar. It was cool with me. I was in hog heaven, working alongside my dad and eating a candy bar for lunch.

Although I was a fairly normal, fun-loving kid, I had one nagging health problem. I had constant bouts with asthma. Every time the leaves fell in Michigan, my asthma would kick up and I had real problems trying to breathe. I spent hours leaning over a pail of Vicks VapoRub and hot water gasping for breath. I hated being cooped up inside when that happened. I couldn’t go out and throw snowballs or play hockey, all the stuff my friends were doing. The doctor took one look at me and told my parents that I needed a change of scenery.

“You’ve got to get this kid out of here,” he said, “to a hotter climate, maybe California.”

As much as Detroit was an integral part of my childhood and while as a family we were very close to our relatives in Michigan, my father and mother had to make a move to greener and sunnier pastures. My parents would look to my Uncle Lefty to help us make the smooth transition. Just like him we decided to make the move to the West Coast and resettle in Southern California.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Fabulous Furniers

I was born Vincent Damon Furnier, named after one of my uncles and Damon Runyon. From the age of ten, I grew up in a religious home; my grandfather was an evangelist and my parents joined his church too. Before then, though, we lived in East Detroit and worshiped baseball. I was the happiest kid in the world.

The Furniers were Huguenots, part French-Canadian people who came over to the New World with the French Protestants in the seventeenth century. They eventually married into some Sioux Indians and a lot of Irish. As a result, two out of three parts of my ethnic background are very alcohol prone. My seventh cousin was the Marquis de Lafayette, the same Lafayette who secured the support of the French during the American Revolution and fought alongside George Washington at Valley Forge. Look at a portrait of Lafayette and you’ll notice the same high cheekbones and long black hair as me. Some say I look just like him, especially when I’m on stage with my sword. I can feel my bloodlines, since swashbuckling comes naturally to me—that’s the French part of me, I guess.

My grandfather, Thurman Sylvester Furnier, was the president of what was called the Church of Jesus Christ. It wasn’t the Church of Latter- day Saints—it wasn’t a Mormon church. In fact, their biggest religious rivals were the Mormons. If you called one of his church members a Mormon, that was like stabbing them in the heart.

My mother was born Ella McCartt in Glenmary, Tennessee. You can’t find Glenmary on a map. It was a whistle-stop. Her mother died when she was very young. She has childhood memories of putting clear liquid into Ball jars for her dad, who was a moonshiner in Glenmary. She had six brothers and sisters, and all of them helped out with the “family business”—and meanwhile the old man kept about forty or fifty thousand dollars in cash buried in the yard. This was in 1946, and at that time, fifty grand was equivalent to about half a million dollars. My grandfather didn’t trust banks.

At age sixteen, around the end of World War II, my mother ran away from home and found her way up to Detroit to work in the factories. That’s where she met my dad, whom people called Mick, though his real name was Ether Maroni Furnier (another Mormon-sounding name). He had just been discharged from the Navy. They were soon married.

I was born in Detroit on February 4, 1948. My first memory of growing up in working-class East Detroit is sitting in a smoke-filled living room with my dad and his brothers, watching Friday-night boxing. There was lots of Carling’s Black Label beer and Lucky Strike cigarettes; I would drink Vernor’s ginger ale. There was always so much smoke in the room, I’m surprised I didn’t contract lung cancer. All the girls stayed in the other room while I sat with the men, my uncles and their buddies, watching the fights on a tiny black-and- white TV set.

Growing up in Detroit was great. I loved my life because my dad and my uncles were so cool. I was the only boy in our family. There was me (Vince) and my sister Nickie, then thirteen cousins, mostly girls. I was the only male left to carry on the Furnier name. So, of course, I ended up legally changing my name to Alice Cooper.

My uncles were Damon Runyon–type characters—tough guys with colorful speech and fascinating stories. Uncle Jocko ran a crooked pool hall in East Detroit. He was my dad’s oldest brother, a spry lightweight prizefighter with a broken nose and not an ounce of fat on him. We all called him Jocko, but his real name was Vincent Collier Furnier. I was named after him. If you wanted to buy anything hot, you went to Jocko’s pool hall. Or if Fast Eddie Felson came in to play Minnesota Fats, that happened at Jocko’s too. It was a famous Detroit dump. During a hot game, the doors would close and lock for hours, sometimes days. My uncle would bring in food and drinks and host the game in exchange for a small cut of the winnings.

Jocko was a swell guy. He used to come over and poke me in the ribs, saying, “Watch that right hook!”

My uncle Lefty, whose real name was Lonson Thurman Furnier, was a whole different deal. He was what you would refer to as a playboy. I never saw Uncle Lefty without a tuxedo, his shirt half-buttoned. He had left Detroit and moved west to Los Angeles, and he worked for Jet Propulsion Labs there. He was the guy who wined and dined the company’s biggest accounts, which is why he was always dressed to the nines. He was part James Bond, part wheeler-dealer—a total Rat Pack– type guy. He would have fit in well with Sinatra and Martin. In fact, he actually hung out with Lana Turner and Ava Gardner, some of the same girls the Rat Pack dated (without my aunt knowing about it, of course).

The great industrial car town of Detroit has always been your classic sports city. The Red Wings were unbeatable. The Pistons were great. Even the Detroit Lions were a really good team at one time. But the Tigers were a religion in our household. They had Ty Cobb, the greatest player of all time, on their team, plus Al Kaline, Mickey Cochrane, Hank Greenberg, and Denny McLain. These were legendary players playing on mythical teams. It was all my dad and I talked about: “What did the Tigers do last night?” I was transfixed with Ernie Harwell’s colorful play-by-play commentary on the radio.

I lived for baseball. When the sun came up, I grabbed my glove and I was ready to play until the sun went down, when you couldn’t see the ball anymore and it was time to rush home for dinner.

East Detroit was a real American melting pot. Each street had their crew—not so much gangs, but characters who banded together as teams. One street over might be all-Italian, while the street after that could be all-black. And next to the blacks were the Irish. Lincoln Street, where I grew up, was principally Polish. People’s names ended in “ski.” Kowalski, Jankowski, Adamski . . . Furnier. We were practically the only non-Polish family on Lincoln. So we were the Polish team. Mornings during baseball season, someone would invariably ask, “Who are we playing today?”

“We’re playing the Irish.”

So we’d walk over to Corktown, the old Irish district. The Irish were cool enough guys. The next day, we’d play the Italians. Hopefully, Bruno wasn’t pitching, because that guy threw hard. We all knew each other, and there weren’t any ethnic or racial problems. Every day a different team, every day a different ethnic nationality. Sandlot rules. No grass. A brand-new baseball was just unheard of. Our baseball had a great big flap coming out of it until it was eventually taped up. Then we batted around a ball wrapped tight in black electrician’s tape. We did whatever we could do, just to play.

I went on to become a pretty good baseball player. One of my best skills was hand-to-eye coordination. I could put the bat on the ball inside or outside the strike zone. If somebody threw a pitch two feet out of the strike zone, low and outside, I could put my bat out and hit it. And I had good rhythm.

My room was a shrine to the Detroit Tigers. No posters, just pictures. A dozen shoe boxes stuffed with baseball cards, cards from packages bought for a nickel apiece, that came with flat squares of bubble gum that congealed into one giant gum brick. I’m sure I had a Mickey Mantle rookie card stashed in there somewhere, along with other cards that could have been worth hundreds or thousands of dollars today if my mother hadn’t thrown them out after I left home. That’s where my allowance went. We traded our cards and flipped doubles. Played tops. When I wasn’t playing baseball or trading cards, I was lying on my bed in my room memorizing batting averages and ERAs. Music wasn’t such a big deal to me. Elvis was out there, and yeah he was cool, but I was addicted to baseball.

On my seventh birthday, my dad got us tickets to a Tigers game at Briggs Stadium. It would be the first time I had seen my heroes play in person. With the game still two months away, I couldn’t sleep. I was a basket case. I was going to see Al Kaline, Harvey Kuenn, Charlie Maxwell, Rocky Colavito, and Jim Bunning.

I remember it distinctly. It was the Tigers vs. the Cleveland Indians, a doubleheader. I remember walking up the ramp of Briggs Stadium and the smell of freshly mowed grass and hot dogs. I remember hearing the cracking sound of batting practice, the sock of a baseball soaring into the outfield. I sat there dumbfounded throughout both games, not moving. I didn’t want a Coke. I didn’t want a hot dog. I didn’t ask for anything. I was afraid if I moved, it was all going to be over. Jim Bunning vs. Herb Score. Charlie Maxwell hit four home runs in two games. We won 7–0 and 8–2 and swept the doubleheader. I went home that night exhausted but in heaven. It was the best day I could ever have imagined. If someone had offered me a choice, Disneyland or a Tigers doubleheader, it would have been a no-brainer: Tigers all the way. To this day, when ESPN flashes MLB scores, I still check to see whether the Tigers won or lost. The Tigers run deep in my psyche.

In our family, there were three basic rules:

1. You had to be a Democrat.

2. You had to pull for the Tigers and the Michigan Wolverines.

3. You had to be American League.

The All-American Detroit family. If you strayed outside any of those rules, it was “What’s wrong with that kid of yours?” While Catholicism was very common and a lot of my friends were Catholic, we didn’t fuss over who was Catholic or who was Protestant. Nobody cared. The black and white thing didn’t exist in my home, nor did we see any difference between the Italians and the Irish. Honestly, if a black guy played baseball, especially if he was a shortstop (a rare commodity), or if he could hit, we simply didn’t see color. The only question was, Is he a power hitter, a singles hitter, or a strikeout pitcher? Was he a good basketball player? Sports was the measuring stick of a person’s worth during my childhood.

Music and sports never mixed back in the neighborhood. Only later did we find out that Rod Stewart could have been a pro soccer player, or that Elton John was a great tennis player. Just recently, in Britain, they listed the top rock-star athletes. For instance, Bruce Dickinson, the lead singer of Iron Maiden, is a highly ranked fencing champion. (I was the only American in their top ten, and rated number two as the golfer on the list.)

And nobody played a game like golf when I was a kid in Detroit. Nobody played tennis, either. A sport in Detroit was considered any activity where you hit somebody or knocked them down. Only five sports existed in our world: baseball, football, hockey, basketball . . . and grand-theft auto. Golf and tennis weren’t even considered sports. They ranked right down there with badminton or girls’ field hockey. Bowling was big, but it wasn’t considered a sport as much as just an excuse to drink on a Saturday night.

Over the years, my dad did many things for a living, things like driving a cab and selling used cars. At the car lot, he worked for a couple of nefarious characters and unfortunately my dad couldn’t sell a used car to save his life! He wasn’t corrupt enough. My dad would be almost through a sale, and just as the poor sucker would be driving away, he would run out across the lot and yell out, “Stop! We turned the odometer back and the whole left side of the car is Bondo!” His bosses would warn him that he had to get out of the business. He was just too honest.

My dad worked strictly on commission, so if he sold a car for $300, he only got about thirty bucks, maximum. I remember going to work with my dad. He would put all his spare change in a cup on top of the icebox, and whatever was in the change cup was our lunch money. If there wasn’t much, then lunch might be just a candy bar. It was cool with me. I was in hog heaven, working alongside my dad and eating a candy bar for lunch.

Although I was a fairly normal, fun-loving kid, I had one nagging health problem. I had constant bouts with asthma. Every time the leaves fell in Michigan, my asthma would kick up and I had real problems trying to breathe. I spent hours leaning over a pail of Vicks VapoRub and hot water gasping for breath. I hated being cooped up inside when that happened. I couldn’t go out and throw snowballs or play hockey, all the stuff my friends were doing. The doctor took one look at me and told my parents that I needed a change of scenery.

“You’ve got to get this kid out of here,” he said, “to a hotter climate, maybe California.”

As much as Detroit was an integral part of my childhood and while as a family we were very close to our relatives in Michigan, my father and mother had to make a move to greener and sunnier pastures. My parents would look to my Uncle Lefty to help us make the smooth transition. Just like him we decided to make the move to the West Coast and resettle in Southern California.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Alice writes like he golfs: straight and right down the middle. Like a lot of us golf addicts, he's spent his fair share of his life getting out of the rough and back onto the green. If you're like me and only read like a book a year (OK, like every decade), this should be the one.”

—John Daly

“What a blast from the past, and such insight to the future! Alice Cooper, Golf Monster shares Alice's personal life mission, interwoven with great stories and characters from the 60's through the present in Rock and Roll. Not to mention some wonderful golf tips and experiences, humorously presented. Thank you Alice, for a nice ride!”

—Michael Douglas, actor and creator of the Michael Douglas & Friends Charity Golf Tournament

“Few things are more surreal than playing golf with a guy named Alice. But by the time you reach the second tee, you realize that No More Mr. Nice Guy is one of the wittiest and engaging playing partners you've ever had. Plus, the guy can play! For those who aren't likely to experience the pleasure of a quiet, leisurely round with the man who spends his nights singing "School's been blown to pieces," this book provides the next best thing.”

—Steve Eubanks, author of Golf Freek

“Debauchery, demons and divots! This is the only book I've ever read that should come in 3-D; the crazy stories come right at you from Sinatra to KISS to the Moscow Golf Club.”

—Gary McCord, author of Golf for Dummies

From the Hardcover edition.

—John Daly

“What a blast from the past, and such insight to the future! Alice Cooper, Golf Monster shares Alice's personal life mission, interwoven with great stories and characters from the 60's through the present in Rock and Roll. Not to mention some wonderful golf tips and experiences, humorously presented. Thank you Alice, for a nice ride!”

—Michael Douglas, actor and creator of the Michael Douglas & Friends Charity Golf Tournament

“Few things are more surreal than playing golf with a guy named Alice. But by the time you reach the second tee, you realize that No More Mr. Nice Guy is one of the wittiest and engaging playing partners you've ever had. Plus, the guy can play! For those who aren't likely to experience the pleasure of a quiet, leisurely round with the man who spends his nights singing "School's been blown to pieces," this book provides the next best thing.”

—Steve Eubanks, author of Golf Freek

“Debauchery, demons and divots! This is the only book I've ever read that should come in 3-D; the crazy stories come right at you from Sinatra to KISS to the Moscow Golf Club.”

—Gary McCord, author of Golf for Dummies

From the Hardcover edition.