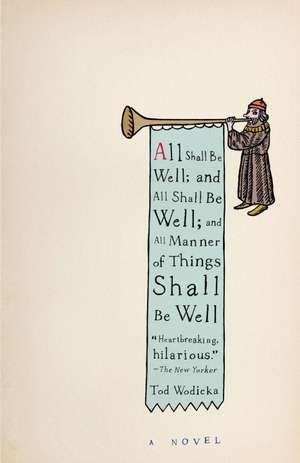

All Shall Be Well; And All Shall Be Well; And All Manner of Things Shall Be Well: Un Programa Probado Para Aprovechar al Maximo el Poder Curativo Natural de su Cuerpo

Autor Tod Wodickaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2008

Preț: 80.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 120

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.35€ • 16.68$ • 12.90£

15.35€ • 16.68$ • 12.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307278876

ISBN-10: 0307278875

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 139 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage

ISBN-10: 0307278875

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 139 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage

Notă biografică

Tod Wodicka was born in Glen Falls, NY, in 1976. He was educated at Manchester University, UK. He lives in Berlin.

Extras

Chapter One

Dawn, or its German equivalent, cannot be far off. But here, at the top of the hill, night still clogs the forest. Being sixty-three years old and sleepy, I find it nearly impossible to differentiate now between the stray grapevines, the trees, and the waist-high shrubs that I know surround me. They could all be wild animals.

'Is everyone awake?'

Three days ago I imprisoned six middle-aged women and one pre-pubescent girl in a tent on this hilltop. The time has come to set them free.

'Pray undo the lock,' an anchorite whispers. Then, sensing my hesitation, 'Did thou forget the key?'

There is no key because there is no lock. My hand waits on the zipper. I stand there in my dagged-edged taffeta tunic, my sandaled feet wet from dew. My bald little head. My nose. Somewhere behind me sleeps the great stone Benedictine Abbey St Hildegard, its vineyards cascading down the hill over Eibingen, over Rudesheim, and into the river Rhine.

Zipper down, the tent gives us Tivona Henry. Forty years old and not unlovely, Tivona is skinny in a way that suggests intense concentration; more simian, maybe, than outright undernourished. Her head feeds a nest of gray-streaked frizz. It's Tivona's medieval chant workshop that I've accompanied on this German vacation. She smiles.

I have only myself to blame. Weeks prior to the journey I'd sowed the idea of re-enacting Hildegard von Bingen's first days in the anchorage, more or less on a lark, knowing full well these women's anchorite longings and their propensity for outlandish re-enactment schemes. I expected nothing to come of it. Then, a day before departure, it was announced that several of the women would be enduring three days in the tent; three entire days and nights atop the hill overlooking the Abbey, reliving Hildegard's girlhood. One meal a day, only wine to drink, no idle chatter, absolutely no grumbling; just chanting and the occasional prayer. I have never had a problem with the concept of medieval re-enactment. In fact, many believe that I actually invented it. The world is riddled with far worse activities and I altogether refuse to even feign embarrassment, especially at my age. Dressing up in period-specific costume? The re-creation of history through practical workshops and group scholarship? For some, in this day and age, there's simply no place left to retreat.

Tivona steps free from the tent. Others follow, one by one. Blinking, grinning heads, then arms, then bodies. Tivona leading her cortege of part-time anchorites back into the twentieth century. Each holds a candle made by the nuns here at the Abbey St Hildegard, most ennobled with now-grotesque melting effigies of their patron saint. White tunics glow in what is left of the moon.

Some stumble, others laugh; they are very obviously inebriated. They sing. Soon I am surrounded, my flame-flickered face a mask of potent infirmities, adhering, so I've been told, to the long tradition of Christian mysticism insisting that those impaired in body are somehow healthier in spirit. Which is another way of saying that because I am ugly I am going to get a reward. Specifically, I have a misshapen nose.

There is a deep silence despite the amateur medieval plainchant which clouds behind me. It's nearing lauds, first light. Single file, we begin our descent back towards the Abbey and the event of our first public performance.

'Burt?' Tivona asks.

In three days the women will return home to Queens Falls, New York. They do not yet know that I have no intention of accompanying them.

'Are you well, m'lord?' Tivona continues.

'No,' I say. 'I am not.'

Two years ago I joined Tivona Henry's medieval chant workshop as a way to better manage the anger that New York State's Board of Parole believed they had good reason to be wary of. Following a late-night Confraternity of Times Lost Regained revel, I'd been apprehended while attempting to transport myself home in a borrowed Saab. I didn't have a license to operate such a vehicle, or any vehicle, or the requisite skills; and, worse, I'd consumed much homemade mead. I really don't remember the specifics. It's a matter of public record, however, that I altogether refused to walk in a straight line or touch my nose with my finger. They'd never detained anybody dressed in period-specific, historically accurate costume before, and once installed in the Queens Falls police depot I was treated genially, like a time traveler who couldn't comprehend the vigorous modernity which had enveloped him. Because I was old they supposed I was demented.

For one thing, they refused to immediately imprison me. This I found offensive. I was made to sit on something aluminum, and handed beverages I could not possibly drink. (Coffee, I did my best to explain, was OOP. Out of Period. Such beans did not exist in medieval Europe, so I assiduously avoided them.) My portrait was snapped, the air from my lungs scientifically tested. To the best of my memory, I was wearing a simple woolen tunic, nothing extravagant or untoward.

'Let's do this one more time. Just for the record, what year is this again?'

I liked the police officer charged with interrogating me. In him I noted the same pious dreaminess that often overtakes a medieval re-enactor after a long, involving Confraternity of Times Lost Regained weekend.

'AD 1256,' I answered. I was inebriated enough to imagine that he would see in me what I saw in him, and that he would not only recognize but applaud our similar life choices. Our costumes.

'Your name?'

'Eckbert Attquiet.'

'Right. This your wallet, Eckbert?'

'It is my pouch.'

The police officer removed some cards from my leather pouch. The first was a wallet-sized, laminated reproduction of a painting of my son, Tristan, and me. Domenico Ghirlandaio's Portrait of an Elderly Man with His Son.

I raised my voice and rose to my feet. I did something which required another police officer to restrain my hands in metal cuffs.

'Take it easy, old man. Nobody is going to steal your library card.' The officer looked at me carefully. Slowly, he placed my Ghirlandaio back inside the pouch. He held another card. 'Burt Hecker,' he read. 'Well, and here's another, also says Burt Hecker. Confraternity of Times Lost Regained. That your thing, Mr Hecker? Medieval re-enactment?'

History, when you devote your life to it, can be either a weight into a premature old age or a release from the troublesome, promiscuous present: eternal immaturity as an occupational boon. Since I was thirty, most have considered me retired, unemployed, or fundamentally unemployable. I have devoted my adult life to amateur scholarship and the Confraternity of Times Lost Regained, the re-enactment society I founded. I've since been left a considerable fortune.

'Mr Hecker?'

The fluorescence made me sneeze. 'I'm just an old man,' I said. 'Do with me what you will.' Telephones trilled and voices barked from small boxes full of static. Flags, bowls of peanuts, guns, computer screens imitating aquariums—lunacy, plain and simple. Me in my tunic and homemade sandals.

'You do not have a New York State driver's license.'

'Correct.'

The CTLR revel had not yet ended when I had absconded, stealing the automobile. It was the first time in my life that I had ever been behind the wheel of such a vehicle. I had had much mead. The last image I recall was of dozens of men, women, and children dressed in all manner of medieval garb—princesses, squires, knights, blacksmiths, peasants, and monks—my twentieth-century secessionists arm in arm around a bonfire, dancing, leaping, singing, with all that desperate blackness surrounding them, pulling at them, devouring the edges of their perfect, historically accurate illusion. Way too much night, I thought. They don't stand a chance. In any event, the idea with the Saab had not been to transport myself to any physical realm.

'Who is Lonna Katsav?'

'What?' Lonna Katsav was my best friend and my lawyer. 'She has nothing to do with this,' I added, finally shocked back into AD 1996. It was Lonna's Saab that I had stolen. On the wall was a framed photograph of the Governor of New York State, and one of the President of the United States. Since when, I wondered, did those wielding great authority begin smiling like nineteenth-century barkers? How could anyone take these men seriously? If everyone loses their mind at the same time does anyone really notice? I looked around me at the game being played, the idea of order and duty and society and justice being re-enacted, that stern idiotic bustle, and I knew, suddenly, that it was all over. I had crashed my best friend's car into a point of no return.

'Well, Lonna Katsav is coming to pick you up.' The police officer offered me a stick of chewing gum. 'She's not going to press charges, you'll be happy to know. Though she thought about it.'

I held up my shackles. I sighed. 'Make sure that she sees me in these at least, would you?'

It should be said that throughout the whole ordeal my officer did an admirable job of not once gawping at my nose. The first fellow I encountered at the station had demanded that I actually remove it, thinking it was part of my medieval garb.

The punishment for drunk driving without a license in a stolen car consisted of a fine and the recommendation that I serve my parole in thrice-weekly Anger Management & Self-Betterment Workshops. However, because my late wife knew some people who knew some people who knew the judge, I was allowed a unique alternative. Thus, I became the first male member of Tivona's medieval music therapy workshop. Truth is, nobody was particularly worried that I'd anger. I rarely did. They simply knew that I would, on principle, risk six months in the threatened cage rather than submit myself to the group hugs with mountain people I was certain such Self-Bettermenting entailed. Better, finally, to chant. Better eighteen months of intuitive healing with Tivona Henry.

From the Hardcover edition.

Dawn, or its German equivalent, cannot be far off. But here, at the top of the hill, night still clogs the forest. Being sixty-three years old and sleepy, I find it nearly impossible to differentiate now between the stray grapevines, the trees, and the waist-high shrubs that I know surround me. They could all be wild animals.

'Is everyone awake?'

Three days ago I imprisoned six middle-aged women and one pre-pubescent girl in a tent on this hilltop. The time has come to set them free.

'Pray undo the lock,' an anchorite whispers. Then, sensing my hesitation, 'Did thou forget the key?'

There is no key because there is no lock. My hand waits on the zipper. I stand there in my dagged-edged taffeta tunic, my sandaled feet wet from dew. My bald little head. My nose. Somewhere behind me sleeps the great stone Benedictine Abbey St Hildegard, its vineyards cascading down the hill over Eibingen, over Rudesheim, and into the river Rhine.

Zipper down, the tent gives us Tivona Henry. Forty years old and not unlovely, Tivona is skinny in a way that suggests intense concentration; more simian, maybe, than outright undernourished. Her head feeds a nest of gray-streaked frizz. It's Tivona's medieval chant workshop that I've accompanied on this German vacation. She smiles.

I have only myself to blame. Weeks prior to the journey I'd sowed the idea of re-enacting Hildegard von Bingen's first days in the anchorage, more or less on a lark, knowing full well these women's anchorite longings and their propensity for outlandish re-enactment schemes. I expected nothing to come of it. Then, a day before departure, it was announced that several of the women would be enduring three days in the tent; three entire days and nights atop the hill overlooking the Abbey, reliving Hildegard's girlhood. One meal a day, only wine to drink, no idle chatter, absolutely no grumbling; just chanting and the occasional prayer. I have never had a problem with the concept of medieval re-enactment. In fact, many believe that I actually invented it. The world is riddled with far worse activities and I altogether refuse to even feign embarrassment, especially at my age. Dressing up in period-specific costume? The re-creation of history through practical workshops and group scholarship? For some, in this day and age, there's simply no place left to retreat.

Tivona steps free from the tent. Others follow, one by one. Blinking, grinning heads, then arms, then bodies. Tivona leading her cortege of part-time anchorites back into the twentieth century. Each holds a candle made by the nuns here at the Abbey St Hildegard, most ennobled with now-grotesque melting effigies of their patron saint. White tunics glow in what is left of the moon.

Some stumble, others laugh; they are very obviously inebriated. They sing. Soon I am surrounded, my flame-flickered face a mask of potent infirmities, adhering, so I've been told, to the long tradition of Christian mysticism insisting that those impaired in body are somehow healthier in spirit. Which is another way of saying that because I am ugly I am going to get a reward. Specifically, I have a misshapen nose.

There is a deep silence despite the amateur medieval plainchant which clouds behind me. It's nearing lauds, first light. Single file, we begin our descent back towards the Abbey and the event of our first public performance.

'Burt?' Tivona asks.

In three days the women will return home to Queens Falls, New York. They do not yet know that I have no intention of accompanying them.

'Are you well, m'lord?' Tivona continues.

'No,' I say. 'I am not.'

Two years ago I joined Tivona Henry's medieval chant workshop as a way to better manage the anger that New York State's Board of Parole believed they had good reason to be wary of. Following a late-night Confraternity of Times Lost Regained revel, I'd been apprehended while attempting to transport myself home in a borrowed Saab. I didn't have a license to operate such a vehicle, or any vehicle, or the requisite skills; and, worse, I'd consumed much homemade mead. I really don't remember the specifics. It's a matter of public record, however, that I altogether refused to walk in a straight line or touch my nose with my finger. They'd never detained anybody dressed in period-specific, historically accurate costume before, and once installed in the Queens Falls police depot I was treated genially, like a time traveler who couldn't comprehend the vigorous modernity which had enveloped him. Because I was old they supposed I was demented.

For one thing, they refused to immediately imprison me. This I found offensive. I was made to sit on something aluminum, and handed beverages I could not possibly drink. (Coffee, I did my best to explain, was OOP. Out of Period. Such beans did not exist in medieval Europe, so I assiduously avoided them.) My portrait was snapped, the air from my lungs scientifically tested. To the best of my memory, I was wearing a simple woolen tunic, nothing extravagant or untoward.

'Let's do this one more time. Just for the record, what year is this again?'

I liked the police officer charged with interrogating me. In him I noted the same pious dreaminess that often overtakes a medieval re-enactor after a long, involving Confraternity of Times Lost Regained weekend.

'AD 1256,' I answered. I was inebriated enough to imagine that he would see in me what I saw in him, and that he would not only recognize but applaud our similar life choices. Our costumes.

'Your name?'

'Eckbert Attquiet.'

'Right. This your wallet, Eckbert?'

'It is my pouch.'

The police officer removed some cards from my leather pouch. The first was a wallet-sized, laminated reproduction of a painting of my son, Tristan, and me. Domenico Ghirlandaio's Portrait of an Elderly Man with His Son.

I raised my voice and rose to my feet. I did something which required another police officer to restrain my hands in metal cuffs.

'Take it easy, old man. Nobody is going to steal your library card.' The officer looked at me carefully. Slowly, he placed my Ghirlandaio back inside the pouch. He held another card. 'Burt Hecker,' he read. 'Well, and here's another, also says Burt Hecker. Confraternity of Times Lost Regained. That your thing, Mr Hecker? Medieval re-enactment?'

History, when you devote your life to it, can be either a weight into a premature old age or a release from the troublesome, promiscuous present: eternal immaturity as an occupational boon. Since I was thirty, most have considered me retired, unemployed, or fundamentally unemployable. I have devoted my adult life to amateur scholarship and the Confraternity of Times Lost Regained, the re-enactment society I founded. I've since been left a considerable fortune.

'Mr Hecker?'

The fluorescence made me sneeze. 'I'm just an old man,' I said. 'Do with me what you will.' Telephones trilled and voices barked from small boxes full of static. Flags, bowls of peanuts, guns, computer screens imitating aquariums—lunacy, plain and simple. Me in my tunic and homemade sandals.

'You do not have a New York State driver's license.'

'Correct.'

The CTLR revel had not yet ended when I had absconded, stealing the automobile. It was the first time in my life that I had ever been behind the wheel of such a vehicle. I had had much mead. The last image I recall was of dozens of men, women, and children dressed in all manner of medieval garb—princesses, squires, knights, blacksmiths, peasants, and monks—my twentieth-century secessionists arm in arm around a bonfire, dancing, leaping, singing, with all that desperate blackness surrounding them, pulling at them, devouring the edges of their perfect, historically accurate illusion. Way too much night, I thought. They don't stand a chance. In any event, the idea with the Saab had not been to transport myself to any physical realm.

'Who is Lonna Katsav?'

'What?' Lonna Katsav was my best friend and my lawyer. 'She has nothing to do with this,' I added, finally shocked back into AD 1996. It was Lonna's Saab that I had stolen. On the wall was a framed photograph of the Governor of New York State, and one of the President of the United States. Since when, I wondered, did those wielding great authority begin smiling like nineteenth-century barkers? How could anyone take these men seriously? If everyone loses their mind at the same time does anyone really notice? I looked around me at the game being played, the idea of order and duty and society and justice being re-enacted, that stern idiotic bustle, and I knew, suddenly, that it was all over. I had crashed my best friend's car into a point of no return.

'Well, Lonna Katsav is coming to pick you up.' The police officer offered me a stick of chewing gum. 'She's not going to press charges, you'll be happy to know. Though she thought about it.'

I held up my shackles. I sighed. 'Make sure that she sees me in these at least, would you?'

It should be said that throughout the whole ordeal my officer did an admirable job of not once gawping at my nose. The first fellow I encountered at the station had demanded that I actually remove it, thinking it was part of my medieval garb.

The punishment for drunk driving without a license in a stolen car consisted of a fine and the recommendation that I serve my parole in thrice-weekly Anger Management & Self-Betterment Workshops. However, because my late wife knew some people who knew some people who knew the judge, I was allowed a unique alternative. Thus, I became the first male member of Tivona's medieval music therapy workshop. Truth is, nobody was particularly worried that I'd anger. I rarely did. They simply knew that I would, on principle, risk six months in the threatened cage rather than submit myself to the group hugs with mountain people I was certain such Self-Bettermenting entailed. Better, finally, to chant. Better eighteen months of intuitive healing with Tivona Henry.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Heartbreaking, hilarious.” —The New Yorker“Disarming and brilliant. . . . A tour de force. . . . Wodicka's prose is a revelation.” —The Boston Globe“Elegant. . . . [Burt's] efforts to hurl himself into the present are chronicled with smart, casually poetic observations. . . . Even if Burt can't transcend time, Wodicka's novel can.” —Entertainment Weekly“This tender, oddball book . . . performs a deft balancing act as it hides love, yearning and regret behind the mouthful of medieval incantation in its title. . . . Startlingly poignant.” —The New York Times Book Review

Descriere

A wildly inventive, mesmerizing, and deeply moving debut novel that features one of the most winning, oddball characters to come along in years.