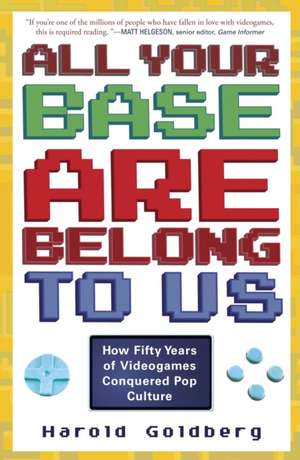

All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture

Autor Harold Goldbergen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2011

Over the last fifty years, video games have grown from curiosities to fads to trends to one of the world's most popular forms of mass entertainment. But as the gaming industry grows in numerous directions and everyone talks about the advance of the moment, few explore and seek to understand the forces behind this profound evolution. How did we get from Space Invaders to Grand Theft Auto? How exactly did gaming become a $50 billion industry and a dominant pop culture form? What are the stories, the people, the innovations, and the fascinations behind this incredible growth?

Through extensive interviews with gaming's greatest innovators, both its icons and those unfairly forgotten by history, All Your Base Are Belong To Us sets out to answer these questions, exposing the creativity, odd theories--and passion--behind the twenty-first century's fastest-growing medium.

Go inside the creation of:

Grand Theft Auto * World of Warcraft * Bioshock * Kings Quest * Bejeweled * Madden Football * Super Mario Brothers * Myst * Pong * Donkey Kong * Crash Bandicoot * The 7th Guest * Tetris * Shadow Complex * Everquest * The Sims * And many more!

Preț: 82.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.83€ • 16.42$ • 13.23£

15.83€ • 16.42$ • 13.23£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307463555

ISBN-10: 0307463559

Pagini: 327

Dimensiuni: 135 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307463559

Pagini: 327

Dimensiuni: 135 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

HAROLD GOLDBERG has reviewed video games for fifteen years for such publications as Wired, Entertainment Weekly, Boys' Life, The Village Voice, and Radar, and for three years penned a widely syndicated gaming column. He has also written on a variety of other subjects for the New York Times, Vanity Fair, Esquire, New York, and Rolling Stone. In addition to his journalism, Goldberg served as editor-in-chief of Sony Online Entertainment during the launch of EverQuest.

Extras

1.

A SPACE ODYSSEY

In 1966, Ralph Baer, a short, bespectacled man with a deep, radio-quality voice and a sharp wit, had been a successful engineer for thirty years, overseeing as many as five hundred employees at Sanders, a large New Hampshire manufacturer whose primary contract was with the United States Defense Department. Much of Baer’s work revolved around airborne radar and antisubmarine warfare electronics. In the late summer of that year, he was sitting on a step outside of the busy Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan, waiting patiently for a colleague and about to head to Madison Avenue for a meeting with a Sanders client. Manhattan’s traffic ebbed and flowed and taxis honked and the passing parade went by. Suddenly, Baer began furiously writing notes with a number 2 pencil on a spiral-bound yellow legal pad. It was like some spirit, some videogame ghost, was doing the writing. When he was done, he had a title page and four single-spaced pages of notes. His brainstorm produced a passel of ideas for an ingenious “game box” he initially called Channel Let’s Play! In that detailed outline, he described Action Games, Board Skill Games, Artistic Games, Instructional Games, Board Change Games, Card Games, and Sports Games, all of which could be played on any of the 40 million cathode-ray-tube TV sets that were ubiquitous in America at the time. He even detailed add-ons, like a pump controller that would allow players to become firemen and put out blazes around a virtual house displayed on-screen.

It wasn’t the first time Baer had come up with an idea for games on TV. Fifteen years earlier, in 1951, he worked at another defense contractor, the Loral Corporation, and suggested a rudimentary checkers game. But he didn’t think about games on TV again until that day in 1966, probably because his boss at Loral thought a game inside a TV was a ludicrous idea.

Let’s Play! was a much grander and more complex idea that would take a lot of time, manpower, and money to create properly. On that summer day in Manhattan, Baer didn’t know how much time or money. But Herb Campman, Sanders’s chief of research and development, believed in the concept and gave Baer a budget of $2,000 for research and $500 for materials. Baer, a complete work addict, would soon be on his way to becoming the father of videogames.

Little has been written about how Baer’s early life informed his later work. In fact, Baer was infected by the invention bug when young, not long after his family left Cologne in the 1930s. As a kid growing up in Germany, Baer didn’t realize the war was coming. He played with a stick and a hoop outdoors. At night, he and his sister performed puppet shows in their bedroom, laughing and laughing as they transported themselves into worlds of their own creation. The childish plays took Baer’s mind off the schoolkids who bullied him and hit him in the face for being a Jew. After packing their possessions into a half dozen three-by-four-foot wooden crates, in August 1938 the teenage Baer and his family fled Hitler’s Germany for New York City, via a ship that docked in Rotterdam. Many of his Jewish relatives weren’t so lucky and were killed. Baer was too young to comprehend the danger; as the ship steamed toward Ellis Island, he spent most of his time in a swimming pool or playing Monopoly with his sister in the game room. Even then, games intrigued him.

The family settled into a courtyard apartment near the Bronx Zoo, and Baer worked at a factory for $12 a week, putting buttons onto cosmetic cases. In the winter, the sixteen-year-old made his first invention: a machine that sped up the process of making leatherette goods. He got the engineering bug when he saw an ad for a correspondence course that read “Big Money Servicing Radios. Be a Genuine ‘Radiotrician.’ ” Baer was so excited about this new radio technology that he began to have dreams about resistors, coils, and capacitors. In a small store on Lexington Avenue, he listened to the radios he fixed, hearing the news of the Blitz on London and the invasion of Poland by the Germans.

By April 1942, Baer was an engineer in World War II as well, learning to prepare roads and bridges for infantry grunts and armored troops. He also laid and removed mines by gingerly digging around in the earth with a bayonet. Life as an engineer turned to life overseas in Bristol, England, teaching military intelligence courses, where he led classes for GIs on subjects such as recognizing German uniforms, ranks, organizational affiliations, and weapons handling. In Tidworth, he and his team created a military intelligence school that trained 120,000 Americans. Part of the school was an immense exhibit hall that included a huge cache of German weapons and vehicles. Ensconced in an industrial hangarlike edifice, the museum was featured in the November 3, 1944, issue of YANKS magazine. In his spare time, Baer secretly wrote a comprehensive manual on weaponry. He kept inventing, even fashioning AM radios from German mine detectors.

The organizational skills Baer learned in the military would serve him well as he began work on his videogame machine. Too, his experiences in the army imbued him with a self-confidence and talent for communication that helped him open up to those above him in rank. He may have been a nerd who cared more about technology than girls, but he was a surprisingly charismatic nerd who didn’t hide away a good idea when he truly believed he had one; he had chutzpah.

His design skills improved as he worked on radio equipment in college in Chicago, and on radar equipment and amplifiers at Transitron, a small company in what is now New York’s Tribeca neighborhood. Soon, Baer was chief engineer and then vice president at Transitron; he moved up the ranks because he was able to get things done quickly and accurately. By the time Sanders Associates made him a chief engineer, he was more of a manager than an inventor. Yet he yearned to get his hands dirty.

The $2,500 Baer received from his boss for developing Let’s Play! may not seem like much now. But in 1966, the sum was enough to purchase a new car, was one third of the amount most Americans earned yearly, and was more than half the cost of the average home. Baer had two men assigned to the project to do the hourly work. Bill Harrison, a hip-looking, conscientious engineering associate, built the prototypes. Bill Rusch, a cranky, temperamental powerhouse who had studied at MIT, came up with the idea of a “machine-controlled ball that would interact with player-controlled ‘paddles.’ ” Both men were already on Sanders’s payroll.

The project was top secret and time-consuming, so much so that Rusch brought a guitar to work so he could blow off steam--leading some curious wall-listeners in the company to believe that Baer was working on some sort of technologically advanced musical instrument, perhaps for the Beatles. But Baer’s boss, Herb Campman, didn’t care about rock ’n’ roll. He gave Baer the money for a sensible reason: He felt the company could eventually make games that would work well in training the military. He was not wrong.

Baer and his wife, Dena, would occasionally canoe in the Merrimack River and walk hand in hand through the Manchester, New Hampshire, snow as it fell. They loved the quaint town. But the weather could be as hostile as the tundra-like blizzards that fell in Capcom’s treacherous Lost Planet. The heavy snows just made Baer work harder. The game box became a consuming project that bordered on obsession. Inventors are like that: zealous to the exclusion of others. It was that way with surveyor George R. Carey, who had the idea for an early TV, the tectroscope, in 1877. It was that way, too, with the twenty-two inventors who tried to make a practical lightbulb after Humphry Davy created incandescent light in 1802, more than seventy-five years before the compulsive Thomas Edison and his team made a bulb that could last twelve hundred hours.

By the time Baer, Harrison, and Rusch were deep into it, the trio had tested many prototype machines, drably named TV Games #1 through #7. To the untrained eye, the inner workings seemed like a vision of chaos. The insides of even the later prototypes looked like a mass of angel hair pasta swirling in a pot of boiling hot water.

Yet the machine worked like magic. It hooked up to a TV’s antenna terminals and used the frequencies of channel 3 or channel 4. On the screen were what Baer called “spots,” little white squares that could be moved around smoothly like a puck on the ice. Attached were two metal boxes that had knobs for vertical and horizontal manipulation. TV Games #1 used four vacuum tubes. There were no circuitry chips; they were luxuries that were too expensive at the time. And there were no transistors. Although Higinbotham used them in his tests, Baer didn’t yet trust transistor technology. But when the box was switched on and that spot moved on-screen for the first time, it was quite the eureka moment. Baer didn’t jump up and down or wave his fist in the air. But inside, he was thrilled and amazed.

What the primitive contraption would do was extraordinary. It would make the television an extension of you, the player. It would let you interact with a square on a black-and-white screen, and if you had even the lamest imagination, it made you believe you were volleying at tennis, aiming carefully as a brave marksman, even playing hero to the innocent as you saved lives.

While the design work proceeded apace, there were continual roadblocks. Worker bees would be called off the project, assigned to work on some secret, pressing defense initiative. At the same time, Sanders executives sometimes seemed aloof and uninterested. In addition, the machine itself became unwieldy. One of the early prototypes was completely impractical, with a chassis that was as large as a kitchen sink. It also looked like something out of high school shop class.

On June 14, 1967, Baer showed Herb Campman a shooting game with a toy gun rigged up with a light mechanism, which interacted with the TV screen. Campman and Sanders’s patent lawyer was impressed enough to call a meeting with the company president and the stodgy board of directors--the next day. Baer had seven games he wanted to show on a color TV set: chess, steeple chase, a fox-and-hounds game, target shooting, a color wheel game, a bucket-filling game, and that firefighter game in which you’d whale on a pump handle like you were trying to get water from a well. If you did it right, water would get to a window in a house. If you failed, the house would go up in flames. On the night before the demo, Baer frantically searched for a script explaining the seven games that he’d recorded circus-barker-style on a sixty-minute Mercury cassette tape. Though he found the tape quickly, Baer was still apprehensive. He tossed and turned in his bed. But he was ready.

The big bosses filed into a dreary conference room on June 15. There was whispering and conferring and the raising of eyebrows during the demonstration. Bill Harrison noticed that Sanders himself was completely uninterested. He was gossiping about a competitor with another colleague. But, ultimately, the suits seemed impressed. Harold Pope, the affable company president who’d come up through the ranks as an engineer, didn’t quite know what to do with what he had seen. Pope’s command to Baer was “Build us something we can sell or license.”

“Build us something we can sell” was a grim declaration that would irk Baer during the next several years. Compared to figuring out how to sell it, getting the console to work properly was the least of his worries. Because gossip had begun among Sanders employees, Baer made sure the work in his ten-by-twenty-foot lab was treated as a top secret project. He told Harrison, “I don’t care if people in the company think we’re making some kind of guitar. I just want to get the job done without a lot of questions from people who aren’t involved.” It was like the first rule of Fight Club. Baer told his team in no uncertain terms, “You don’t talk about TV Games.”

In February 1967, the three created the Quiz Light Pen, which, when attached to TV Games, could be used for an educational instruction and game show-like experience. “Just point it at the screen and click a button to make it work,” announced Baer in impresario mode as he spoke to the camera in a primitive half-hour black-and-white instructional video, which showed how aiming the pen at small boxes on the screen could be used to answer multiple choice questions. Maybe it could even be used for a game show, thought Baer, like Jeopardy!

The inventiveness didn’t stop there. In a memo stamped “Company Private,” Baer also made plans for a steering wheel for racing games and a device that would let you make artistic drawings on the TV screen. There was a baseball game and a strange ESP-like number guessing game. There would be a peripheral for a golf game that included a putter. There was skeet shooting, soccer, and horse racing, too. And there was a cool, addictive version of a Ping-Pong game, the game that people would play the most. (It was also a game that would soon be ripped off, become more popular than Baer ever imagined, and herald a very nasty lawsuit.)

Admittedly, these games were all done with “spots,” not high-quality artwork. To make the games feel more real, the team designed plastic overlays that, through static electricity, stuck to the TV screen. They looked like Howard Johnson restaurant place mats but were somewhat transparent. There was no masterful artwork to the overlays, but the best of them resembled the most dramatic back glass art on pinball games of the day. The first joysticks included were two controllers that had horizontal and vertical abilities and knobs to add English to the ball, somewhat like Tennis for Two (which Baer said he never saw at the Brookhaven National Laboratory).

More ideas for technology and games spewed forth, and so did some manna from heaven: $8,000 more from Sanders’s Campman. The goal in early 1968 was to beef up the console’s circuitry to make it a leaner, meaner machine. Rusch was also able to make those all-important square spots circular, even star-shaped. Initially, Rusch preened, thinking he had done something as historic as translating the Dead Sea Scrolls. Baer was totally enthused, too, until they found a problem with the spots. They moved randomly when they weren’t supposed to. They ran up or down or to the side like feral animals. Sometimes, they’d even change their shapes. Baer decided to stick with the square spots, even though Rusch put up a fuss. This was a constant cycle between the two. Baer would try to mend fences with Rusch. He’d seem OK for a while. Then he’d go off the rails and get angry again.

A SPACE ODYSSEY

In 1966, Ralph Baer, a short, bespectacled man with a deep, radio-quality voice and a sharp wit, had been a successful engineer for thirty years, overseeing as many as five hundred employees at Sanders, a large New Hampshire manufacturer whose primary contract was with the United States Defense Department. Much of Baer’s work revolved around airborne radar and antisubmarine warfare electronics. In the late summer of that year, he was sitting on a step outside of the busy Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan, waiting patiently for a colleague and about to head to Madison Avenue for a meeting with a Sanders client. Manhattan’s traffic ebbed and flowed and taxis honked and the passing parade went by. Suddenly, Baer began furiously writing notes with a number 2 pencil on a spiral-bound yellow legal pad. It was like some spirit, some videogame ghost, was doing the writing. When he was done, he had a title page and four single-spaced pages of notes. His brainstorm produced a passel of ideas for an ingenious “game box” he initially called Channel Let’s Play! In that detailed outline, he described Action Games, Board Skill Games, Artistic Games, Instructional Games, Board Change Games, Card Games, and Sports Games, all of which could be played on any of the 40 million cathode-ray-tube TV sets that were ubiquitous in America at the time. He even detailed add-ons, like a pump controller that would allow players to become firemen and put out blazes around a virtual house displayed on-screen.

It wasn’t the first time Baer had come up with an idea for games on TV. Fifteen years earlier, in 1951, he worked at another defense contractor, the Loral Corporation, and suggested a rudimentary checkers game. But he didn’t think about games on TV again until that day in 1966, probably because his boss at Loral thought a game inside a TV was a ludicrous idea.

Let’s Play! was a much grander and more complex idea that would take a lot of time, manpower, and money to create properly. On that summer day in Manhattan, Baer didn’t know how much time or money. But Herb Campman, Sanders’s chief of research and development, believed in the concept and gave Baer a budget of $2,000 for research and $500 for materials. Baer, a complete work addict, would soon be on his way to becoming the father of videogames.

Little has been written about how Baer’s early life informed his later work. In fact, Baer was infected by the invention bug when young, not long after his family left Cologne in the 1930s. As a kid growing up in Germany, Baer didn’t realize the war was coming. He played with a stick and a hoop outdoors. At night, he and his sister performed puppet shows in their bedroom, laughing and laughing as they transported themselves into worlds of their own creation. The childish plays took Baer’s mind off the schoolkids who bullied him and hit him in the face for being a Jew. After packing their possessions into a half dozen three-by-four-foot wooden crates, in August 1938 the teenage Baer and his family fled Hitler’s Germany for New York City, via a ship that docked in Rotterdam. Many of his Jewish relatives weren’t so lucky and were killed. Baer was too young to comprehend the danger; as the ship steamed toward Ellis Island, he spent most of his time in a swimming pool or playing Monopoly with his sister in the game room. Even then, games intrigued him.

The family settled into a courtyard apartment near the Bronx Zoo, and Baer worked at a factory for $12 a week, putting buttons onto cosmetic cases. In the winter, the sixteen-year-old made his first invention: a machine that sped up the process of making leatherette goods. He got the engineering bug when he saw an ad for a correspondence course that read “Big Money Servicing Radios. Be a Genuine ‘Radiotrician.’ ” Baer was so excited about this new radio technology that he began to have dreams about resistors, coils, and capacitors. In a small store on Lexington Avenue, he listened to the radios he fixed, hearing the news of the Blitz on London and the invasion of Poland by the Germans.

By April 1942, Baer was an engineer in World War II as well, learning to prepare roads and bridges for infantry grunts and armored troops. He also laid and removed mines by gingerly digging around in the earth with a bayonet. Life as an engineer turned to life overseas in Bristol, England, teaching military intelligence courses, where he led classes for GIs on subjects such as recognizing German uniforms, ranks, organizational affiliations, and weapons handling. In Tidworth, he and his team created a military intelligence school that trained 120,000 Americans. Part of the school was an immense exhibit hall that included a huge cache of German weapons and vehicles. Ensconced in an industrial hangarlike edifice, the museum was featured in the November 3, 1944, issue of YANKS magazine. In his spare time, Baer secretly wrote a comprehensive manual on weaponry. He kept inventing, even fashioning AM radios from German mine detectors.

The organizational skills Baer learned in the military would serve him well as he began work on his videogame machine. Too, his experiences in the army imbued him with a self-confidence and talent for communication that helped him open up to those above him in rank. He may have been a nerd who cared more about technology than girls, but he was a surprisingly charismatic nerd who didn’t hide away a good idea when he truly believed he had one; he had chutzpah.

His design skills improved as he worked on radio equipment in college in Chicago, and on radar equipment and amplifiers at Transitron, a small company in what is now New York’s Tribeca neighborhood. Soon, Baer was chief engineer and then vice president at Transitron; he moved up the ranks because he was able to get things done quickly and accurately. By the time Sanders Associates made him a chief engineer, he was more of a manager than an inventor. Yet he yearned to get his hands dirty.

The $2,500 Baer received from his boss for developing Let’s Play! may not seem like much now. But in 1966, the sum was enough to purchase a new car, was one third of the amount most Americans earned yearly, and was more than half the cost of the average home. Baer had two men assigned to the project to do the hourly work. Bill Harrison, a hip-looking, conscientious engineering associate, built the prototypes. Bill Rusch, a cranky, temperamental powerhouse who had studied at MIT, came up with the idea of a “machine-controlled ball that would interact with player-controlled ‘paddles.’ ” Both men were already on Sanders’s payroll.

The project was top secret and time-consuming, so much so that Rusch brought a guitar to work so he could blow off steam--leading some curious wall-listeners in the company to believe that Baer was working on some sort of technologically advanced musical instrument, perhaps for the Beatles. But Baer’s boss, Herb Campman, didn’t care about rock ’n’ roll. He gave Baer the money for a sensible reason: He felt the company could eventually make games that would work well in training the military. He was not wrong.

Baer and his wife, Dena, would occasionally canoe in the Merrimack River and walk hand in hand through the Manchester, New Hampshire, snow as it fell. They loved the quaint town. But the weather could be as hostile as the tundra-like blizzards that fell in Capcom’s treacherous Lost Planet. The heavy snows just made Baer work harder. The game box became a consuming project that bordered on obsession. Inventors are like that: zealous to the exclusion of others. It was that way with surveyor George R. Carey, who had the idea for an early TV, the tectroscope, in 1877. It was that way, too, with the twenty-two inventors who tried to make a practical lightbulb after Humphry Davy created incandescent light in 1802, more than seventy-five years before the compulsive Thomas Edison and his team made a bulb that could last twelve hundred hours.

By the time Baer, Harrison, and Rusch were deep into it, the trio had tested many prototype machines, drably named TV Games #1 through #7. To the untrained eye, the inner workings seemed like a vision of chaos. The insides of even the later prototypes looked like a mass of angel hair pasta swirling in a pot of boiling hot water.

Yet the machine worked like magic. It hooked up to a TV’s antenna terminals and used the frequencies of channel 3 or channel 4. On the screen were what Baer called “spots,” little white squares that could be moved around smoothly like a puck on the ice. Attached were two metal boxes that had knobs for vertical and horizontal manipulation. TV Games #1 used four vacuum tubes. There were no circuitry chips; they were luxuries that were too expensive at the time. And there were no transistors. Although Higinbotham used them in his tests, Baer didn’t yet trust transistor technology. But when the box was switched on and that spot moved on-screen for the first time, it was quite the eureka moment. Baer didn’t jump up and down or wave his fist in the air. But inside, he was thrilled and amazed.

What the primitive contraption would do was extraordinary. It would make the television an extension of you, the player. It would let you interact with a square on a black-and-white screen, and if you had even the lamest imagination, it made you believe you were volleying at tennis, aiming carefully as a brave marksman, even playing hero to the innocent as you saved lives.

While the design work proceeded apace, there were continual roadblocks. Worker bees would be called off the project, assigned to work on some secret, pressing defense initiative. At the same time, Sanders executives sometimes seemed aloof and uninterested. In addition, the machine itself became unwieldy. One of the early prototypes was completely impractical, with a chassis that was as large as a kitchen sink. It also looked like something out of high school shop class.

On June 14, 1967, Baer showed Herb Campman a shooting game with a toy gun rigged up with a light mechanism, which interacted with the TV screen. Campman and Sanders’s patent lawyer was impressed enough to call a meeting with the company president and the stodgy board of directors--the next day. Baer had seven games he wanted to show on a color TV set: chess, steeple chase, a fox-and-hounds game, target shooting, a color wheel game, a bucket-filling game, and that firefighter game in which you’d whale on a pump handle like you were trying to get water from a well. If you did it right, water would get to a window in a house. If you failed, the house would go up in flames. On the night before the demo, Baer frantically searched for a script explaining the seven games that he’d recorded circus-barker-style on a sixty-minute Mercury cassette tape. Though he found the tape quickly, Baer was still apprehensive. He tossed and turned in his bed. But he was ready.

The big bosses filed into a dreary conference room on June 15. There was whispering and conferring and the raising of eyebrows during the demonstration. Bill Harrison noticed that Sanders himself was completely uninterested. He was gossiping about a competitor with another colleague. But, ultimately, the suits seemed impressed. Harold Pope, the affable company president who’d come up through the ranks as an engineer, didn’t quite know what to do with what he had seen. Pope’s command to Baer was “Build us something we can sell or license.”

“Build us something we can sell” was a grim declaration that would irk Baer during the next several years. Compared to figuring out how to sell it, getting the console to work properly was the least of his worries. Because gossip had begun among Sanders employees, Baer made sure the work in his ten-by-twenty-foot lab was treated as a top secret project. He told Harrison, “I don’t care if people in the company think we’re making some kind of guitar. I just want to get the job done without a lot of questions from people who aren’t involved.” It was like the first rule of Fight Club. Baer told his team in no uncertain terms, “You don’t talk about TV Games.”

In February 1967, the three created the Quiz Light Pen, which, when attached to TV Games, could be used for an educational instruction and game show-like experience. “Just point it at the screen and click a button to make it work,” announced Baer in impresario mode as he spoke to the camera in a primitive half-hour black-and-white instructional video, which showed how aiming the pen at small boxes on the screen could be used to answer multiple choice questions. Maybe it could even be used for a game show, thought Baer, like Jeopardy!

The inventiveness didn’t stop there. In a memo stamped “Company Private,” Baer also made plans for a steering wheel for racing games and a device that would let you make artistic drawings on the TV screen. There was a baseball game and a strange ESP-like number guessing game. There would be a peripheral for a golf game that included a putter. There was skeet shooting, soccer, and horse racing, too. And there was a cool, addictive version of a Ping-Pong game, the game that people would play the most. (It was also a game that would soon be ripped off, become more popular than Baer ever imagined, and herald a very nasty lawsuit.)

Admittedly, these games were all done with “spots,” not high-quality artwork. To make the games feel more real, the team designed plastic overlays that, through static electricity, stuck to the TV screen. They looked like Howard Johnson restaurant place mats but were somewhat transparent. There was no masterful artwork to the overlays, but the best of them resembled the most dramatic back glass art on pinball games of the day. The first joysticks included were two controllers that had horizontal and vertical abilities and knobs to add English to the ball, somewhat like Tennis for Two (which Baer said he never saw at the Brookhaven National Laboratory).

More ideas for technology and games spewed forth, and so did some manna from heaven: $8,000 more from Sanders’s Campman. The goal in early 1968 was to beef up the console’s circuitry to make it a leaner, meaner machine. Rusch was also able to make those all-important square spots circular, even star-shaped. Initially, Rusch preened, thinking he had done something as historic as translating the Dead Sea Scrolls. Baer was totally enthused, too, until they found a problem with the spots. They moved randomly when they weren’t supposed to. They ran up or down or to the side like feral animals. Sometimes, they’d even change their shapes. Baer decided to stick with the square spots, even though Rusch put up a fuss. This was a constant cycle between the two. Baer would try to mend fences with Rusch. He’d seem OK for a while. Then he’d go off the rails and get angry again.

Recenzii

"A love letter to gaming...filled with fascinating behind-the-scenes vignettes of game creation…perfectly encapsulates the passion and dedication of videogames’ creators and fans."—Abbie Heppe, senior producer, G4TV

"The best window into the video game industry on the market today."—Steve Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games

"Harold Goldberg’s portrait of a weird, often dysfunctional and amazing video game industry makes a great, great read."—Ken Levine, co-founder and creative director, Irrational Games

"Indispensable…Goldberg takes us inside the hearts and minds of the hackers, hustlers, engineers, and dreamers who changed electronic entertainment forever."--Matt Helgeson, senior editor, Game Informer

"A story as riveting and addictive as the games it explores…If you’ve ever wanted someone to explain how and why video games captured the world’s imagination, this is the book for you."--James Ledbetter, editor in charge, Reuters.com

"The best window into the video game industry on the market today."—Steve Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games

"Harold Goldberg’s portrait of a weird, often dysfunctional and amazing video game industry makes a great, great read."—Ken Levine, co-founder and creative director, Irrational Games

"Indispensable…Goldberg takes us inside the hearts and minds of the hackers, hustlers, engineers, and dreamers who changed electronic entertainment forever."--Matt Helgeson, senior editor, Game Informer

"A story as riveting and addictive as the games it explores…If you’ve ever wanted someone to explain how and why video games captured the world’s imagination, this is the book for you."--James Ledbetter, editor in charge, Reuters.com

Descriere

In the first narrative history of video games, Goldberg shows the people and forces that have made gaming an indelible part of pop culture--and an industry whose revenues now rival Hollywood's.