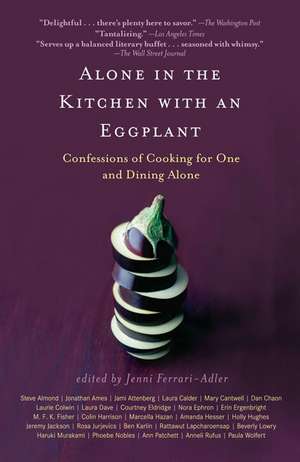

Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant: Confessions of Cooking for One and Dining Alone

Editat de Jenni Ferrari-Adleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2008 – vârsta de la 18 ani

In this delightful and much buzzed-about essay collection, 26 food writers like Nora Ephron, Laurie Colwin, Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and M. F. K. Fisher invite readers into their kitchens to reflect on the secret meals and recipes for one person that they relish when no one else is looking.

Part solace, part celebration, part handbook, Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant offers a wealth of company, inspiration, and humor—and finally, solo recipes in these essays about food that require no division or subtraction, for readers of Gabrielle Hamilton's Blood, Bones &Butter and Tamar Adler's The Everlasting Meal.

Featuring essays by:

Steve Almond, Jonathan Ames, Jami Attenberg, Laura Calder, Mary Cantwell, Dan Chaon, Laurie Colwin, Laura Dave, Courtney Eldridge, Nora Ephron, Erin Ergenbright, M. F. K. Fisher, Colin Harrison, Marcella Hazan, Amanda Hesser, Holly Hughes, Jeremy Jackson, Rosa Jurjevics, Ben Karlin, Rattawut Lapcharoensap, Beverly Lowry, Haruki Murakami, Phoebe Nobles, Ann Patchett, Anneli Rufus and Paula Wolfert.

View our feature on the essay collection Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant.

Part solace, part celebration, part handbook, Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant offers a wealth of company, inspiration, and humor—and finally, solo recipes in these essays about food that require no division or subtraction, for readers of Gabrielle Hamilton's Blood, Bones &Butter and Tamar Adler's The Everlasting Meal.

Featuring essays by:

Steve Almond, Jonathan Ames, Jami Attenberg, Laura Calder, Mary Cantwell, Dan Chaon, Laurie Colwin, Laura Dave, Courtney Eldridge, Nora Ephron, Erin Ergenbright, M. F. K. Fisher, Colin Harrison, Marcella Hazan, Amanda Hesser, Holly Hughes, Jeremy Jackson, Rosa Jurjevics, Ben Karlin, Rattawut Lapcharoensap, Beverly Lowry, Haruki Murakami, Phoebe Nobles, Ann Patchett, Anneli Rufus and Paula Wolfert.

View our feature on the essay collection Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant.

Preț: 133.39 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.52€ • 26.65$ • 21.08£

25.52€ • 26.65$ • 21.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781594483134

ISBN-10: 1594483132

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 138 x 212 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

ISBN-10: 1594483132

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 138 x 212 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Notă biografică

Jenni Ferrari-Adler is a graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Michigan, where she received an MFA in fiction. She has worked as a reader for The Paris Review, a bookseller, an egg-seller, and is an agent at Union Literary Agents. Her short fiction has been published in numerous magazines.

@JenFerrariAdler

@JenFerrariAdler

Extras

Introduction Call it seven-thirty on a Wednesday night. No one else is home. A slight hunger hums in your body, so you wander into the kitchen. In front of the window a plant's stems wave like arms from their hanging basket. In the pantry bin, potatoes eye the onions slipping out of their skins. An apron hangs from the closet door like the shadow of a companion. Reflexively, you open the refrigerator and nod at the condiments, grab the hot sauce, and close the others back into cold darkness. Bottle of sauce in hand, you gaze around the room, inspecting the contents of the cabinets, the pile of paper menus from nearby restaurants, the spines of your cookbooks. You turn from the bookshelf and catch a glimpse of yourself in the window. In the heat, your hair has puffed wildly. You experience one of those weird lost minutes inside your head. Loneliness, you think, loneliness with its lyrical sound; you look like a lone lioness. You hear Alvy Singer, the young Woody Allen character from Annie Hall, say, "The universe is expanding." Bananas Shaughnessy from The House of Blue Leaves cuts him off: "My troubles all began a year ago—two years ago today— Two days ago today? Today." Then you remember your mother mixing cream cheese and lox into a pan of scrambling eggs.

You don't need a literal eggplant on hand to realize—with the pleasurable shock that comes from recognizing a small truth—that you are alone in the kitchen with one.

This book had its genesis in August 2004, when I spent the first of many such nights alone in Michigan. I was twenty-seven, a born-and-raised New Yorker, and I'd never lived by myself before. It was unsettling to be without a job or roommates, to have so much time alone in my tiny house in Ann Arbor. As a graduate student in fiction writing, I spent a few hours each day at my desk, following my characters around and trying to get them into interesting trouble. That left a lot of downtime. I ran on the treadmill at the YMCA, hiked in the arboretum, and drank many solitary cups of coffee. I hauled my laptop and bag from one cafÈ to another until it started to seem as if the hauling itself were my job. I was seeking, I suppose, some form of company and conversation, even if the majority of conversations were ones I merely overheard.

In my first semester I took a literature course, Exile and Homecoming, that contributed to my somewhat indulgent delusion that I was in exile. Where was the subway? Where were the bodegas and stoops? Where was my mother? Through the windows of my house I watched the neighbors rake leaves in the autumn and shovel snow in the winter. On the floor of my kitchen was a hopeful dog bowl—I didn't have a dog—and on the refrigerator were photographs of a boyfriend, a family, and friends. I had a life but I seemed to have abandoned it. Some days it required an act of will to believe my life still existed or mattered.

"Why does living alone feel so familiar?" I asked my little brother one night on the phone. He was living in a studio apartment in Philadelphia.

"Because it's like being alone," he said.

He was right, of course. Being alone—battling loneliness—was something at which I had always felt it was important to improve. Taking solitude in stride was a sign of strength and of a willingness to take care of myself. This meant—among other things—working productively, remembering to leave the house, and eating well. I thought about food all the time. I had subscriptions to Gourmet and Food &Wine. Cooking for others had often been my way of offering care. So why, when I was alone, did I find myself trying to subsist on cereal and water? I'd need to learn to cook for one.

It wasn't my first time in the Midwest. I'd done my undergraduate work—as I was learning to call it—at Oberlin College, which boasts many strange and wonderful things, one of which is a system of eating cooperatives. Students can opt out of the dining hall and into one of the communal dining rooms—if a room that seats eighty with folding chairs at round tables and is swept three times a day but is always dirty can be called a dining room. The kitchen featured four industrial-size mixers, two walk-in coolers, and a wok so enormous it doubled as a sled in winter. On the kitchen prep team, I diced eighty onions, wearing sunglasses that didn't stop my tears. When none of the vegetables I ordered came in on time, I still had to produce a stir-fry. I stood on a stool and begged brown rice not to burn. In some ways, learning to cook at Oberlin resembled learning to cook in a restaurant, only it was less precise. The diners charged the food the moment we set the big pots down.

After college, I followed the graduated masses to Brooklyn. I moved into a railroad apartment with two friends who had also gone through Oberlin's cooperative system. It seemed natural to us to make dinner together every night, and I gradually learned to cook for smaller groups. One of my roommates worked at the farmers' market and always brought home bags of vegetables. I worked, briefly, at a bakery in the neighborhood. At the end of the day I brought home bread; I had literally become the breadwinner of our makeshift household. Often, we had guests to dinner. We carried the food from the kitchen down the long hallway to the living room. We sat on the floor.

Over the next five years, we moved from neighborhood to neighborhood in Brooklyn. First, my boyfriend moved in with my friends and me. Later, he and I moved into our own place. Cooking for two was hard. I always made too much.

Now, marooned in the Midwest once again, I tried to live on a stipend. I tried to remember how to make friends. After class, I asked two girls if they wanted to go to a movie over the weekend and the asking made me blush. I tried to string together late-night telephone calls and infrequent visits into an approximation of a relationship. I missed eating salad and cheese with my boyfriend and going over the stories of our days. I missed the texture and chaos of daily life shared with others.

But if time were money, I was rich. There were hours, at least in the beginning, everywhere I looked. In addition to time, I had a galley kitchen, a shelf of cookbooks, two heavy pots, and a chef's knife. I lived near the farmers' market, a cooperative grocery, and a butcher shop. My bicycle had a basket. Which is all to say it was an excellent domestic setup.

But not only did I like to cook for others, I liked to cook with others. Would cooking alone be depressing? More or less depressing than living on sandwiches? More or less depressing than takeout?

"A potato," I told my brother, when he asked what I'd eaten for dinner. "Boiled, cubed, sautéed with olive oil, sea salt, and balsamic vinegar."

"That's it?" he asked. He was one to talk. He'd enjoyed what he called "bachelor's taco night" for three dinners and counting.

"A red cabbage, steamed, with hot sauce and soy sauce," I said the following night.

"Do you need some money?" he asked.

But it wasn't that, or it wasn't only that. I liked to think of myself not as a student on a budget, but rather as a peasant, a member of a group whose eating habits, across cultures, had long appealed to me.

"Are you full?" my brother asked.

"Full enough," I said.

"What about protein?"

Later that week, I diced two onions and sautéed them until they turned translucent and transformed the kitchen with their comforting smell. Flanked by books and magazines, I ate straight out of the pot at the table, my knees curled up to my chest. Aimee Mann sang from the stereo: One is the loneliest number. Everything, I realized, growing light-headed, anything was delicious. In the next weeks I continued on in phases, first everything raw, then everything baked. I prioritized condiments. What wasn't delicious with Sriracha Hot Chili Sauce?

One night, I invited a few people from my program to dinner. For them, I made a salad with romaine lettuce, radishes, string beans, scallions, homemade croutons, and goat cheese. For them, I served dessert—pistachio nuts and chocolate chips in ramekins, a combination discovered via random out-of-cabinet consumption. At my nudging, surely, the conversation turned to the topic of cooking for ourselves. One woman's solitary dish was spaghetti carbonara. It satisfied her cravings for bacon, eggs, and pasta, and it made good leftovers. One man mixed couscous with canned soup. We agreed that dividing recipes by four was depressing, and that in cooking for ourselves, presentation went out the window.

When I considered it later, though, I had to admit I liked my personal presentation: the red pot with the flat wooden serving spoon, a half sheet of paper towel for a napkin. I liked my mismatched thrift-store plates, chopsticks, and canning jars. I even liked, I'm sorry to say, eating sandwiches while walking to class.

There was real pleasure to be had eating ice cream out of the container and pickles out of a glass jar, standing up at the counter. I wondered whether the cravings associated with pregnancy were really only a matter of women feeling empowered to admit their odd longings to their husbands, to ask another person to bring them the eccentric combinations they'd long enjoyed in private. If I'd been able to completely forget about nutrition, I might have created a diet based only on pickles and ice cream, salty and sweet.

Alas, I was somewhat conscious of the link between what I ate and my health, and so the next night—having eaten all the ice cream and pickles in the house—I mixed black beans and brown rice. I couldn't help smiling to myself when I thought of the man from my dinner party fluffing couscous alone in his kitchen across town. Sharing stories of eating alone had made me less lonely.

After a stressful deadline in February—that bleak month when Ann Arbor hibernates and people hurry, hunched over in ski jackets, through the dark—I decided to reward myself with a good meal. I made Amanda Hesser's Airplane Salad: Bibb lettuce, white beans, smoked trout, and a sherry vinaigrette. While I ate, I read her essay "Single Cuisine."

"I know many women who have a set of home-alone foods," writes Hesser. "My friend Aleksandra, for instance, leans toward foods that are white in color."

My pulse quickened as though Hesser were whispering in my ear. This was all I really wanted—to be let in on other people's secrets. What better place to start than in their kitchens?

Remembering Laurie Colwin's essay "Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant," I quickly went to my living room and plucked the friendly Home Cooking from my bookshelf. I sat with the yellow paperback on my black couch. I giggled at the description of Colwin's absurdly small Greenwich Village apartment, "the coziest place on earth," where she did dishes in the bathtub. She'd brought her kitchen into my living room. My breathing deepened with gratitude. The connectedness I felt was the opposite of the drifting into space I'd experienced whenever I spent more than three consecutive nights alone. We read to feel close to people we don't know, to get into other people's heads. I get the same sensation of intimacy from following a recipe. I began to scheme: Hesser, Colwin, and me . . . maybe I could break the silence and help men and women everywhere be less alone together.

Because cooks love the social aspect of food, cooking for one is intrinsically interesting. A good meal is like a present, and it can feel goofy, at best, to give yourself a present. On the other hand, there is something life affirming in taking the trouble to feed yourself well, or even decently. Cooking for yourself allows you to be strange or decadent or both. The chances of liking what you make are high, but if it winds up being disgusting, you can always throw it away and order a pizza; no one else will ever know. In the end, the experimentation, the impulsiveness, and the invention that such conditions allow for will probably make you a better cook.

As the days lengthened and warmed and the town revealed itself again, I peered tentatively into the windows of restaurants. I read the menus and contemplated going inside to tell the hostess, "Just me."

In her classic essay "A Is for Dining Alone," M. F. K. Fisher proclaims: "Enough of hit-or-miss suppers of tinned soup and boxed biscuits and an occasional egg just because I had failed once more to rate an invitation."

Don't we all think about the experience of dining alone in restaurants? Women tend to both romanticize and fear it. We have a shared image of an enigmatic woman pulling off a solitary dinner with style, perhaps in Europe. I think men have less trouble with it, though I'm not sure. It's certainly easier if you sit at the counter, or if the hour is off—three is a nice time for lunch by yourself; lunch is easier than dinner—or if other patrons are eating by themselves, or if you have a book with you, or better yet, two books.

My friend Rachel won't do it, not under any conditions. It's because, she says, her family moved around so frequently when she was growing up and she spent a lot of time worrying about sitting alone in the cafeteria.

With the exception of a recent barbecue chicken salad at T.G.I. Friday's in the Detroit Metro Airport, I tend to enjoy solitary dining. I like sitting at a sushi bar by myself, watching the chef work. Or at a counter, where I can have an omelet and a bottomless cup of coffee and stay a long time.

The more interaction with a waiter required, the more challenging it becomes for me to maintain my cool. In truth, it doesn't take much—one couple seated too close, an intrusive waiter—for the experience to spin me off into the murk of self-pity.

As mentioned, my boyfriend was anywhere but here. He was in New York, acquiring and editing books. He was always on the lookout for new projects. I told him I had a great idea, either for the imprint where he worked or for another imprint at his company that published cookbooks: an anthology of essays on cooking for one and dining alone that could function as a cookbook as well as a lifting-off point for readers to follow their instincts and create their own idiosyncratic meals.

I wanted someone to create this book so I could have a copy. I imagined it as a friendly presence in my kitchen for those nights when I cooked for myself. When my boyfriend suggested I put the book together, as a kind of summer job, I was surprised and resistant. It sounded like a lot of work. It sounded complicated. But eventually I was persuaded. Who could make the precise book I imagined better than me?

The more I thought about it, the more surprised I was that a book like this didn't already exist. A quick search on Amazon turned up some books on cooking for one, but they tended toward the pragmatic; their focus was logistical and dietary, and not on the rich experience of solitary cooking and eating. I noted with a mixture of amusement and trepidation that based on my search words—"cooking for one"—the website suggested I might be interested in books on the subject of cookery for people with mental disabilities. I didn't find a single book on the subject of dining alone. It started to seem as if we were talking about a phenomenon that hadn't yet been recognized as a phenomenon. It started to seem like anthropology. Or sociology. Or something that belonged on the Discovery Channel.

The boyfriend, on a weekend trip to Ann Arbor, drove me to the library, where we pored over indexes looking for the words one, alone, solitary, single, etc. I wrote a proposal and found an agent, and early in the summer the project sold.

I put together a wish list of food and fiction writers and invited them to participate in the project. I asked them: Do you have a secret meal you make (or used to make) for yourself? Do you have a set of rituals for dining alone (at home or in a restaurant), or rules?

To my surprise, they responded, often enthusiastically. Some seemed as if they'd been waiting a long time to be asked.

Rosa Jurjevics, daughter of the late Laurie Colwin, responded to my invitation almost immediately, writing, in part:

I'm not much of a cook, I'm afraid to say, but I have a few funny meals that I do like to cobble together. They are mostly comprised of comfort food from my childhood growing up with my mother, strange foods we both loved due to our collective salt tooth. All autumn essays floated into my computer's inbox. How good it was to know that Ann Patchett used to eat oatmeal in Provincetown, like a plow horse, like generations of Patchetts before her; that Beverly Lowry and Marcella Hazan eat anchovies; that Ben Karlin makes a sauce that changed the very course of his life! Some contributors react to their parents—Dan Chaon prepares a spicier, wilder chili than his mother used to cook; Anneli Rufus, free from her mother's rules against carbohydrates, revels in making plain, starchy meals (and, like Amanda Hesser's friend, she wants them white). There are fantasies: Phoebe Nobles transforms for a season into the Asparagus Superhero; Jeremy Jackson sings the song of the black bean; Holly Hughes, the mother of three young children, imagines what she would cook if she could cook only for herself. Colin Harrison, drawing on decades of solitary lunches, searches for his next regular restaurant. Laura Dave's tale of cooking not only ends in but directly causes romantic love. On the flip side, Jonathan Ames poisons himself with expired eggs, then basks in the comfort provided by the kind and bosomy waitress at his local diner. Erin Ergenbright writes from the perspective of a waitress serving a finicky solo diner and provides a recipe from the restaurant. Courtney Eldridge, not yet willing to produce the dishes her ex-husband, a chef, taught her to make, offers her mother's salsa recipe. Jami Attenberg braves a hotel buffet at a resort before retreating to the safety of room service.

With repeated readings I was able to inhabit each essay. I walked to Ann Arbor's Kerrytown Market to buy the ingredients for Steve Almond's quesaritos. At Steve's suggestion, I asked the fishmonger for tiger-tail shrimp to make myself seem cool. I made Jeremy Jackson's black beans and rice and thought of Jeremy up to his arms in dried beans. I wrapped myself up in a kimono and ate Nora Ephron's mashed potatoes, a perfect predecessor to Laura Calder's Kippers Mash, comfort food for a queen. It's almost impossible to make Marcella Hazan's tost without thinking of how her husband calls her mangia panini (sandwich eater), or Paula Wolfert's pa amb tomàquet without conjuring up her day of pure Mediterranean bliss, or Ben Karlin's salsa rosa without thinking about hash and Italy. If you do as Laura Dave instructs and listen to "Atlantic City" and drink two glasses of wine while you make beef stroganoff, it will be hard not to be swept into Laura's Manhattan, in which all things lonely and difficult become romantic, glazed with youth and hope. This book abounds with recipes, tips, idiosyncratic truths passed kitchen to kitchen, mouth to mouth.

My friend Rachel—she of the cafeteria fear—works for a nonprofit that advocates for independent farms. She feels weird mentioning my book to her colleagues, since their organization believes in community dining. I think this concern is intriguing but ultimately beside the point. My book is by no means a suggestion to eat alone; even the most community minded among us must occasionally find ourselves hungry and alone in the house. There are various reasons for solitary dining, only some of them a result of loss in its numerous forms. We adjust to solitude and an increased responsibility for caring for ourselves as we grow older, as we leave home for the first time, as we move, as our circumstances change. We dine alone once or for a brief time or for a long time.

I'm interested in finding out what happens then. Do we hold to the same standards that apply to cooking for others? Usually not, it seems. I'm interested in why.

In "Making Soup in Buffalo," Beverly Lowry writes: "The fact was, I wanted the same thing again and again. And so I yielded, bought the goods, took them home, cooked, ate, accompanied usually by music, preferably a public radio station that played music I liked. And I am here to tell you, the pleasure never diminished. I was happy every time."

Every time I read those sentences, I take a big breath and let it out with a sigh. Good, I think. I'll make the same weird meal I've been making all week—half a loaf of seven-grain bread sliced and slathered with tahini and honey—again tonight. It's what I want. It's delicious and filling.

It is my hope that some nights in your kitchen you will reach for this book and be comforted and laugh out loud with recognition—and try another recipe. These are essays to be read and reread, to be stained with gravy and wine. I've tried to assemble the book so it reads fluidly from beginning to end. Arranging the pieces gave me the sensation of designing the seating chart for the most wonderful dinner party in the world. The book can also be read backward, and each essay stands alone. In that way it is like a cookbook, like cooking. Of course, this anthology is by no means exhaustive; it is merely an entryway.

If you choose to give this book to yourself, to keep it in your kitchen, my hope is that it will give you some company, some inspiration, and some recipes that require no division or subtraction. I hope it will remind you that alone and lonely are not synonymous; you will have yourself—and the food you love—for company.

In conclusion, let me just say that a scoop of vanilla ice cream with a handful of walnuts (or broken pretzels) and maple syrup, served in a coffee cup, makes a perfect dessert for one person cross-legged on a couch, or, if it's warm out, on a porch or a stoop.

As an alternative—if right now you're rolling your eyes and thinking, not so much with the ice cream—allow me to recommend Fage Total 0% Greek yogurt with one teaspoon of honey mixed in. The honey does something not only to the flavor but to the texture of the yogurt, making it sublimely creamy and sweet. I like to use the teaspoon to eat the dessert out of the container. While I eat, I daydream about the dinner parties I will throw in the shimmering future, when I will serve this yogurt-and-honey creation in champagne glasses and be applauded for my culinary brilliance.

But for now, eating this in bed by myself is not merely fine, it is sweet.

You don't need a literal eggplant on hand to realize—with the pleasurable shock that comes from recognizing a small truth—that you are alone in the kitchen with one.

This book had its genesis in August 2004, when I spent the first of many such nights alone in Michigan. I was twenty-seven, a born-and-raised New Yorker, and I'd never lived by myself before. It was unsettling to be without a job or roommates, to have so much time alone in my tiny house in Ann Arbor. As a graduate student in fiction writing, I spent a few hours each day at my desk, following my characters around and trying to get them into interesting trouble. That left a lot of downtime. I ran on the treadmill at the YMCA, hiked in the arboretum, and drank many solitary cups of coffee. I hauled my laptop and bag from one cafÈ to another until it started to seem as if the hauling itself were my job. I was seeking, I suppose, some form of company and conversation, even if the majority of conversations were ones I merely overheard.

In my first semester I took a literature course, Exile and Homecoming, that contributed to my somewhat indulgent delusion that I was in exile. Where was the subway? Where were the bodegas and stoops? Where was my mother? Through the windows of my house I watched the neighbors rake leaves in the autumn and shovel snow in the winter. On the floor of my kitchen was a hopeful dog bowl—I didn't have a dog—and on the refrigerator were photographs of a boyfriend, a family, and friends. I had a life but I seemed to have abandoned it. Some days it required an act of will to believe my life still existed or mattered.

"Why does living alone feel so familiar?" I asked my little brother one night on the phone. He was living in a studio apartment in Philadelphia.

"Because it's like being alone," he said.

He was right, of course. Being alone—battling loneliness—was something at which I had always felt it was important to improve. Taking solitude in stride was a sign of strength and of a willingness to take care of myself. This meant—among other things—working productively, remembering to leave the house, and eating well. I thought about food all the time. I had subscriptions to Gourmet and Food &Wine. Cooking for others had often been my way of offering care. So why, when I was alone, did I find myself trying to subsist on cereal and water? I'd need to learn to cook for one.

It wasn't my first time in the Midwest. I'd done my undergraduate work—as I was learning to call it—at Oberlin College, which boasts many strange and wonderful things, one of which is a system of eating cooperatives. Students can opt out of the dining hall and into one of the communal dining rooms—if a room that seats eighty with folding chairs at round tables and is swept three times a day but is always dirty can be called a dining room. The kitchen featured four industrial-size mixers, two walk-in coolers, and a wok so enormous it doubled as a sled in winter. On the kitchen prep team, I diced eighty onions, wearing sunglasses that didn't stop my tears. When none of the vegetables I ordered came in on time, I still had to produce a stir-fry. I stood on a stool and begged brown rice not to burn. In some ways, learning to cook at Oberlin resembled learning to cook in a restaurant, only it was less precise. The diners charged the food the moment we set the big pots down.

After college, I followed the graduated masses to Brooklyn. I moved into a railroad apartment with two friends who had also gone through Oberlin's cooperative system. It seemed natural to us to make dinner together every night, and I gradually learned to cook for smaller groups. One of my roommates worked at the farmers' market and always brought home bags of vegetables. I worked, briefly, at a bakery in the neighborhood. At the end of the day I brought home bread; I had literally become the breadwinner of our makeshift household. Often, we had guests to dinner. We carried the food from the kitchen down the long hallway to the living room. We sat on the floor.

Over the next five years, we moved from neighborhood to neighborhood in Brooklyn. First, my boyfriend moved in with my friends and me. Later, he and I moved into our own place. Cooking for two was hard. I always made too much.

Now, marooned in the Midwest once again, I tried to live on a stipend. I tried to remember how to make friends. After class, I asked two girls if they wanted to go to a movie over the weekend and the asking made me blush. I tried to string together late-night telephone calls and infrequent visits into an approximation of a relationship. I missed eating salad and cheese with my boyfriend and going over the stories of our days. I missed the texture and chaos of daily life shared with others.

But if time were money, I was rich. There were hours, at least in the beginning, everywhere I looked. In addition to time, I had a galley kitchen, a shelf of cookbooks, two heavy pots, and a chef's knife. I lived near the farmers' market, a cooperative grocery, and a butcher shop. My bicycle had a basket. Which is all to say it was an excellent domestic setup.

But not only did I like to cook for others, I liked to cook with others. Would cooking alone be depressing? More or less depressing than living on sandwiches? More or less depressing than takeout?

"A potato," I told my brother, when he asked what I'd eaten for dinner. "Boiled, cubed, sautéed with olive oil, sea salt, and balsamic vinegar."

"That's it?" he asked. He was one to talk. He'd enjoyed what he called "bachelor's taco night" for three dinners and counting.

"A red cabbage, steamed, with hot sauce and soy sauce," I said the following night.

"Do you need some money?" he asked.

But it wasn't that, or it wasn't only that. I liked to think of myself not as a student on a budget, but rather as a peasant, a member of a group whose eating habits, across cultures, had long appealed to me.

"Are you full?" my brother asked.

"Full enough," I said.

"What about protein?"

Later that week, I diced two onions and sautéed them until they turned translucent and transformed the kitchen with their comforting smell. Flanked by books and magazines, I ate straight out of the pot at the table, my knees curled up to my chest. Aimee Mann sang from the stereo: One is the loneliest number. Everything, I realized, growing light-headed, anything was delicious. In the next weeks I continued on in phases, first everything raw, then everything baked. I prioritized condiments. What wasn't delicious with Sriracha Hot Chili Sauce?

One night, I invited a few people from my program to dinner. For them, I made a salad with romaine lettuce, radishes, string beans, scallions, homemade croutons, and goat cheese. For them, I served dessert—pistachio nuts and chocolate chips in ramekins, a combination discovered via random out-of-cabinet consumption. At my nudging, surely, the conversation turned to the topic of cooking for ourselves. One woman's solitary dish was spaghetti carbonara. It satisfied her cravings for bacon, eggs, and pasta, and it made good leftovers. One man mixed couscous with canned soup. We agreed that dividing recipes by four was depressing, and that in cooking for ourselves, presentation went out the window.

When I considered it later, though, I had to admit I liked my personal presentation: the red pot with the flat wooden serving spoon, a half sheet of paper towel for a napkin. I liked my mismatched thrift-store plates, chopsticks, and canning jars. I even liked, I'm sorry to say, eating sandwiches while walking to class.

There was real pleasure to be had eating ice cream out of the container and pickles out of a glass jar, standing up at the counter. I wondered whether the cravings associated with pregnancy were really only a matter of women feeling empowered to admit their odd longings to their husbands, to ask another person to bring them the eccentric combinations they'd long enjoyed in private. If I'd been able to completely forget about nutrition, I might have created a diet based only on pickles and ice cream, salty and sweet.

Alas, I was somewhat conscious of the link between what I ate and my health, and so the next night—having eaten all the ice cream and pickles in the house—I mixed black beans and brown rice. I couldn't help smiling to myself when I thought of the man from my dinner party fluffing couscous alone in his kitchen across town. Sharing stories of eating alone had made me less lonely.

After a stressful deadline in February—that bleak month when Ann Arbor hibernates and people hurry, hunched over in ski jackets, through the dark—I decided to reward myself with a good meal. I made Amanda Hesser's Airplane Salad: Bibb lettuce, white beans, smoked trout, and a sherry vinaigrette. While I ate, I read her essay "Single Cuisine."

"I know many women who have a set of home-alone foods," writes Hesser. "My friend Aleksandra, for instance, leans toward foods that are white in color."

My pulse quickened as though Hesser were whispering in my ear. This was all I really wanted—to be let in on other people's secrets. What better place to start than in their kitchens?

Remembering Laurie Colwin's essay "Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant," I quickly went to my living room and plucked the friendly Home Cooking from my bookshelf. I sat with the yellow paperback on my black couch. I giggled at the description of Colwin's absurdly small Greenwich Village apartment, "the coziest place on earth," where she did dishes in the bathtub. She'd brought her kitchen into my living room. My breathing deepened with gratitude. The connectedness I felt was the opposite of the drifting into space I'd experienced whenever I spent more than three consecutive nights alone. We read to feel close to people we don't know, to get into other people's heads. I get the same sensation of intimacy from following a recipe. I began to scheme: Hesser, Colwin, and me . . . maybe I could break the silence and help men and women everywhere be less alone together.

Because cooks love the social aspect of food, cooking for one is intrinsically interesting. A good meal is like a present, and it can feel goofy, at best, to give yourself a present. On the other hand, there is something life affirming in taking the trouble to feed yourself well, or even decently. Cooking for yourself allows you to be strange or decadent or both. The chances of liking what you make are high, but if it winds up being disgusting, you can always throw it away and order a pizza; no one else will ever know. In the end, the experimentation, the impulsiveness, and the invention that such conditions allow for will probably make you a better cook.

As the days lengthened and warmed and the town revealed itself again, I peered tentatively into the windows of restaurants. I read the menus and contemplated going inside to tell the hostess, "Just me."

In her classic essay "A Is for Dining Alone," M. F. K. Fisher proclaims: "Enough of hit-or-miss suppers of tinned soup and boxed biscuits and an occasional egg just because I had failed once more to rate an invitation."

Don't we all think about the experience of dining alone in restaurants? Women tend to both romanticize and fear it. We have a shared image of an enigmatic woman pulling off a solitary dinner with style, perhaps in Europe. I think men have less trouble with it, though I'm not sure. It's certainly easier if you sit at the counter, or if the hour is off—three is a nice time for lunch by yourself; lunch is easier than dinner—or if other patrons are eating by themselves, or if you have a book with you, or better yet, two books.

My friend Rachel won't do it, not under any conditions. It's because, she says, her family moved around so frequently when she was growing up and she spent a lot of time worrying about sitting alone in the cafeteria.

With the exception of a recent barbecue chicken salad at T.G.I. Friday's in the Detroit Metro Airport, I tend to enjoy solitary dining. I like sitting at a sushi bar by myself, watching the chef work. Or at a counter, where I can have an omelet and a bottomless cup of coffee and stay a long time.

The more interaction with a waiter required, the more challenging it becomes for me to maintain my cool. In truth, it doesn't take much—one couple seated too close, an intrusive waiter—for the experience to spin me off into the murk of self-pity.

As mentioned, my boyfriend was anywhere but here. He was in New York, acquiring and editing books. He was always on the lookout for new projects. I told him I had a great idea, either for the imprint where he worked or for another imprint at his company that published cookbooks: an anthology of essays on cooking for one and dining alone that could function as a cookbook as well as a lifting-off point for readers to follow their instincts and create their own idiosyncratic meals.

I wanted someone to create this book so I could have a copy. I imagined it as a friendly presence in my kitchen for those nights when I cooked for myself. When my boyfriend suggested I put the book together, as a kind of summer job, I was surprised and resistant. It sounded like a lot of work. It sounded complicated. But eventually I was persuaded. Who could make the precise book I imagined better than me?

The more I thought about it, the more surprised I was that a book like this didn't already exist. A quick search on Amazon turned up some books on cooking for one, but they tended toward the pragmatic; their focus was logistical and dietary, and not on the rich experience of solitary cooking and eating. I noted with a mixture of amusement and trepidation that based on my search words—"cooking for one"—the website suggested I might be interested in books on the subject of cookery for people with mental disabilities. I didn't find a single book on the subject of dining alone. It started to seem as if we were talking about a phenomenon that hadn't yet been recognized as a phenomenon. It started to seem like anthropology. Or sociology. Or something that belonged on the Discovery Channel.

The boyfriend, on a weekend trip to Ann Arbor, drove me to the library, where we pored over indexes looking for the words one, alone, solitary, single, etc. I wrote a proposal and found an agent, and early in the summer the project sold.

I put together a wish list of food and fiction writers and invited them to participate in the project. I asked them: Do you have a secret meal you make (or used to make) for yourself? Do you have a set of rituals for dining alone (at home or in a restaurant), or rules?

To my surprise, they responded, often enthusiastically. Some seemed as if they'd been waiting a long time to be asked.

Rosa Jurjevics, daughter of the late Laurie Colwin, responded to my invitation almost immediately, writing, in part:

I'm not much of a cook, I'm afraid to say, but I have a few funny meals that I do like to cobble together. They are mostly comprised of comfort food from my childhood growing up with my mother, strange foods we both loved due to our collective salt tooth. All autumn essays floated into my computer's inbox. How good it was to know that Ann Patchett used to eat oatmeal in Provincetown, like a plow horse, like generations of Patchetts before her; that Beverly Lowry and Marcella Hazan eat anchovies; that Ben Karlin makes a sauce that changed the very course of his life! Some contributors react to their parents—Dan Chaon prepares a spicier, wilder chili than his mother used to cook; Anneli Rufus, free from her mother's rules against carbohydrates, revels in making plain, starchy meals (and, like Amanda Hesser's friend, she wants them white). There are fantasies: Phoebe Nobles transforms for a season into the Asparagus Superhero; Jeremy Jackson sings the song of the black bean; Holly Hughes, the mother of three young children, imagines what she would cook if she could cook only for herself. Colin Harrison, drawing on decades of solitary lunches, searches for his next regular restaurant. Laura Dave's tale of cooking not only ends in but directly causes romantic love. On the flip side, Jonathan Ames poisons himself with expired eggs, then basks in the comfort provided by the kind and bosomy waitress at his local diner. Erin Ergenbright writes from the perspective of a waitress serving a finicky solo diner and provides a recipe from the restaurant. Courtney Eldridge, not yet willing to produce the dishes her ex-husband, a chef, taught her to make, offers her mother's salsa recipe. Jami Attenberg braves a hotel buffet at a resort before retreating to the safety of room service.

With repeated readings I was able to inhabit each essay. I walked to Ann Arbor's Kerrytown Market to buy the ingredients for Steve Almond's quesaritos. At Steve's suggestion, I asked the fishmonger for tiger-tail shrimp to make myself seem cool. I made Jeremy Jackson's black beans and rice and thought of Jeremy up to his arms in dried beans. I wrapped myself up in a kimono and ate Nora Ephron's mashed potatoes, a perfect predecessor to Laura Calder's Kippers Mash, comfort food for a queen. It's almost impossible to make Marcella Hazan's tost without thinking of how her husband calls her mangia panini (sandwich eater), or Paula Wolfert's pa amb tomàquet without conjuring up her day of pure Mediterranean bliss, or Ben Karlin's salsa rosa without thinking about hash and Italy. If you do as Laura Dave instructs and listen to "Atlantic City" and drink two glasses of wine while you make beef stroganoff, it will be hard not to be swept into Laura's Manhattan, in which all things lonely and difficult become romantic, glazed with youth and hope. This book abounds with recipes, tips, idiosyncratic truths passed kitchen to kitchen, mouth to mouth.

My friend Rachel—she of the cafeteria fear—works for a nonprofit that advocates for independent farms. She feels weird mentioning my book to her colleagues, since their organization believes in community dining. I think this concern is intriguing but ultimately beside the point. My book is by no means a suggestion to eat alone; even the most community minded among us must occasionally find ourselves hungry and alone in the house. There are various reasons for solitary dining, only some of them a result of loss in its numerous forms. We adjust to solitude and an increased responsibility for caring for ourselves as we grow older, as we leave home for the first time, as we move, as our circumstances change. We dine alone once or for a brief time or for a long time.

I'm interested in finding out what happens then. Do we hold to the same standards that apply to cooking for others? Usually not, it seems. I'm interested in why.

In "Making Soup in Buffalo," Beverly Lowry writes: "The fact was, I wanted the same thing again and again. And so I yielded, bought the goods, took them home, cooked, ate, accompanied usually by music, preferably a public radio station that played music I liked. And I am here to tell you, the pleasure never diminished. I was happy every time."

Every time I read those sentences, I take a big breath and let it out with a sigh. Good, I think. I'll make the same weird meal I've been making all week—half a loaf of seven-grain bread sliced and slathered with tahini and honey—again tonight. It's what I want. It's delicious and filling.

It is my hope that some nights in your kitchen you will reach for this book and be comforted and laugh out loud with recognition—and try another recipe. These are essays to be read and reread, to be stained with gravy and wine. I've tried to assemble the book so it reads fluidly from beginning to end. Arranging the pieces gave me the sensation of designing the seating chart for the most wonderful dinner party in the world. The book can also be read backward, and each essay stands alone. In that way it is like a cookbook, like cooking. Of course, this anthology is by no means exhaustive; it is merely an entryway.

If you choose to give this book to yourself, to keep it in your kitchen, my hope is that it will give you some company, some inspiration, and some recipes that require no division or subtraction. I hope it will remind you that alone and lonely are not synonymous; you will have yourself—and the food you love—for company.

In conclusion, let me just say that a scoop of vanilla ice cream with a handful of walnuts (or broken pretzels) and maple syrup, served in a coffee cup, makes a perfect dessert for one person cross-legged on a couch, or, if it's warm out, on a porch or a stoop.

As an alternative—if right now you're rolling your eyes and thinking, not so much with the ice cream—allow me to recommend Fage Total 0% Greek yogurt with one teaspoon of honey mixed in. The honey does something not only to the flavor but to the texture of the yogurt, making it sublimely creamy and sweet. I like to use the teaspoon to eat the dessert out of the container. While I eat, I daydream about the dinner parties I will throw in the shimmering future, when I will serve this yogurt-and-honey creation in champagne glasses and be applauded for my culinary brilliance.

But for now, eating this in bed by myself is not merely fine, it is sweet.

Descriere

In this delightful and unexpected collection, writers, foodies, and others ruminate on the distinctive experiences of cooking for one and dining alone.