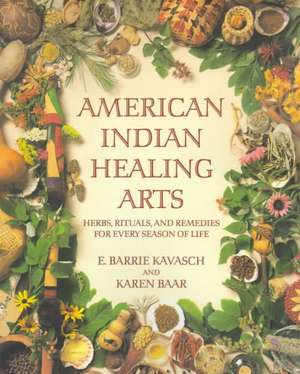

American Indian Healing Arts: Herbs, Rituals, and Remedies for Every Season of Life: Healing Arts

Autor E. Barrie Kavasch, Kavasch, BAARen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 1999

Here are the time-honored tribal rituals performed to promote good health, heal illness, and bring mind and spirit into harmony with nature. Here also are dozens of safe, effective earth remedies--many of which are now being confirmed by modern research.

Each chapter introduces a new stage in the life cycle, from the delightful Navajo First Smile Ceremony (welcoming a new baby) to the Apache Sunrise Ceremony (celebrating puberty) to the Seminole Old People's Dance.

At the heart of the book are more than sixty easy-to-use herbal remedies--including soothing rubs for baby, a yucca face mask for troubled skin, relaxing teas, massage oils, natural insect repellents, and fragrant smudge sticks. There are also guidelines for assembling a basic American Indian medicine chest.

Preț: 129.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 194

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.79€ • 26.93$ • 20.84£

24.79€ • 26.93$ • 20.84£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553378818

ISBN-10: 0553378813

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 190 x 234 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Healing Arts

ISBN-10: 0553378813

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 190 x 234 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Healing Arts

Notă biografică

E. Barrie Kavasch is an herbalist, ethnobotanist, mycologist, and food historian of Cherokee, Creek, and Powhatan descent, with Scotch-Irish, English, and German heritage as well. She is the author of two books on Native American foods, Enduring Harvests (1995, Globe Pequot) and Native Harvests (1979, Random House), which was hailed by The New York Times as "the most intelligent and brilliantly researched book on the foods of the American Indians." She has studied with many acclaimed native healers--some of whom contributed to this book--and is a research associate of the Institute for American Indian Studies in Washington, Connecticut. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Martha Stewart Living, and many other publications, and she has been a guest lecturer at the New York Botanical Garden, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Yale Peabody Museum.

Karen Baar has a degree in public health from the Yale University School of Medicine and writes about gardening and health for The New York Times, Self, Good Housekeeping, and Natural Health, among other publications.

Karen Baar has a degree in public health from the Yale University School of Medicine and writes about gardening and health for The New York Times, Self, Good Housekeeping, and Natural Health, among other publications.

Extras

Introduction: Healing the Traditional Way

It may be that some little root of the Sacred Tree still lives. Nourish it then, that it may leaf and bloom and fill with singing birds. Hear me, not for myself, but for my people; I am old. Hear me that they may once more go back into the sacred hoop and find the Good Red Road, the shielding tree.

--Black Elk, Oglala Sioux holy man and medicine man

This book explores the healing arts of American Indians. Our native tribes had and still perform a dazzling array of healing rituals; they also know and use hundreds of herbs, fungi, lichens, and other natural materials. Although many of these practices are ancient, they remain vital. Today healers from all over the world--Europe, Australia, India, and China--come to the United States to learn how to use our native medicinal plants. But ironically, many Americans have not yet tapped into this distinctively American tradition, instead choosing European herbal medicine, homeopathy, or acupuncture in their quest for alternatives to conventional medical treatment.

But American Indian healing goes well beyond treating disease. As we approach the end of the twentieth century it offers a rich resource for people who want to connect, both collectively and individually, with their spiritual selves. Throughout their sweeping history, American Indians have held the spiritual side of life to be primary and sacred. Their belief system provides them with a deep and nurturing connection to the earth and the spiritual realm.

Birth and Infancy: "Thank You For Coming To Our Village"

When a new baby is born among the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Clan Mothers welcome the newborn by saying: "Thank you for coming to our village; we hope you will stay with us."

--Katsi Cook, Mohawk midwife from Akwesasne and a research fellow in the American Indian Program at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York

The cry of a newborn child is music to which all people respond. American Indians place special emphasis on welcoming a child not only into the family but also into the tribe and the world. When a baby is born, he emerges from his mother's womb into the womb of Mother Earth.

Of course, childbirth was not always such a smooth transition. In early societies women frequently gave birth outside the village in less-than-ideal or even dangerous situations. Often they were alone and exposed to the elements. But most American Indian women were well equipped to manage within their environments. They were in vigorous good health and quite fit throughout their pregnancies, so that birthing was fairly spontaneous and without much trauma or pause from their normal work. Early records tell of women giving birth in challenging circumstances and then walking great distances with their newborns on their backs.

But not every birth was comfortable or successful. Infant deaths and abnormalities occurred, and mothers died in childbirth or of infections or complications immediately after giving birth.

Across the continent, as native people settled into village life they developed a broad array of ceremonies, rituals, prayers, and special herbs and medicines to protect and sanctify this important life passage. Each tribe used its own sequence of prayers and offerings of sacred substances to ease labor and delivery for the mother and help ensure the infant's survival.

Today, as long as there are no complications, many American Indian mothers choose to give birth at home or in specially prepared family settings. Birthing outside of the hospital allows women to continue to honor their traditional tribal rituals. But even hospital birth need not impede some of the smaller, more private ceremonies. And because some rites take place before labor begins as well as after the baby arrives at home, many people can avail themselves of these special blessings.

In some tribes, rituals for the birth mother begin just before or during labor and delivery. Among the Diné or Navajo, for example, a woman can request that a Blessing Way, or "No Sleep," be done for her before she leaves for the hospital or as she prepares for the birth at home. The name "No Sleep" means a one-night sing; it is much like a vigil. The medicine man sings for her from late evening until "the dawn has a white stripe" in order to ensure that her labor and delivery will be normal and as easy as possible, and that her baby will be healthy and whole.

Birthing practices during and immediately after the birth frequently combine the sacred and the practical. Often part of the midwife's work during labor is to sing to and massage the laboring woman, bathe her in healing herbs, and ritually wash her abdomen, breasts, arms, and legs. In many cultures women do this for themselves, continuing a practice they began during the latter part of pregnancy. The midwife uses sacred herbs and important herbs of childbearing such as sweetgrass, hawthorn berries, or leaves of raspberry, strawberry, bearberry, or juniper submerged in either river or lake water. Not only do these herbs bless the process, they also relax the mother, ease the delivery, and nurture a pure, strong spirit in the baby. In some tribes midwives use other mild herbs, such as blue cohosh root, to gently speed the birth.

After the delivery, the focus is on the baby. A birth attendant ritually bathes the baby in a sacred herbal wash. Relatives may look the infant over for any unusual markings or other signs. For example, among the Delaware, knowledgeable elders read a birthmark as a special sign that means--depending on its size and configuration--good luck or a long life. Sometimes the mark may be attributed to the mother's or father's dream; in other cases it is an indication that either or both parents experienced difficulties with other people.

On occasion family members attending the birth may see an ancient wisdom in the infant's eyes or recognize the soul of an ancestor. In special instances it becomes clear at birth--or sometimes even before--that this particular baby has been blessed and summoned to a specific calling. In the past, a boy might have been dedicated to the path of a great warrior or directed to follow a favored uncle into a secret society. A girl infant might be consecrated to fertility, to skill in tanning, or to the mineral, animal, herbal, and fungal wisdom of the earth.

Families, especially those suffering from the previous loss of one or more children, feel a special urgency about strengthening a just-born member of the family in this way. Many Indian children rebel against this idea, refusing to follow the life path that the tribe has chosen for them. But there are amazing stories of individuals who eventually come around to occupy the roles envisioned for them at birth.

Spiderwebs, the Earliest Dream Catchers

Today's popular dream catchers have their roots in ancient amulets called spiderwebs. Loving family members--parents, aunts, uncles, and siblings--created these graceful ephemeral designs of quill and beadwork on hide. The spiderweb, which can also be seen on early birch-bark scrolls, was a charm meant to hold good energy. And like a true spiderweb, this one could catch everything, especially harm coming from the spirit world or anywhere else, before it reached the baby.

The Great Lakes Algonquian and the Cree of Canada and the central United States were particularly likely to use these charms, whose designs were echoed on the blankets and clothing of the infant. Today these powerful talismans have come to be called dream catchers.

Welcoming a new child does not always involve elaborate ceremony. Paula Dove Jennings, of the Turtle Clan, is a Niantic-Narragansett oral historian. Among her people, traditions center on women. Growing up in Charlestown, Rhode Island, she recalls being told that when she was born, on July 3, 1940--the first daughter of Pretty Flower and Roaring Bull--her father walked out onto their street, raised his arms, and shouted, "Now I am a man!" to celebrate her birth. Her older brother, Red Earth, was a well-loved toddler, yet the importance of having a girl had to be publicly proclaimed.

Sometimes a rite is a small but significant act, such as the sprinkling of sacred cornmeal. Quiet prayers and other private practices, such as making a medicine bundle, dream catcher, or other special amulet, are sometimes all that are needed to work a bit of magic.

For example, Kwakiutl mothers, who live on the Northwest Coast of the United States, perform the Girl Child Prosperity Ceremony so that their baby girls grow to be healthy, industrious, and accomplished women. After preparing special birth amulets, which her infant daughter will wear or carry close until she is nine months old, the mother prays: "O, supernatural power of the Supernatural One of the Rocks, go on, look at what I am doing to you, for I pray you to take mercy on my child and, please, let her be successful in getting property and let nothing evil happen to her when she goes up the mountain picking all kinds of berries; and, please, protect her, Supernatural One."

American Indians weave prayers--large and small--into many aspects of their lives. This is especially true when it comes to the rituals, ceremonies, and other symbolic events that mark passages through an individual's life. Each tribe and culture group has its own unique way of praying. While a great deal has changed because of Christian influences and missionaries' work over the past five hundred years, the strongest traditions are still alive.

Prayers are usually long, melodic, and haunting. They are frequently offered to the sky, the Creator, and the universe. Many prayers use one or more of the most highly valued sacred substances--tobacco, cornmeal, pollen, bearberry, sweetgrass, sage, and cedar. Prayers unite the finest tribal traditions and beliefs with an individual's most personal feelings. The supplicant speaks, cries, or sings the prayer, shouting or loudly emphasizing certain parts. Many prayers are filled with earnest tears of sadness, love, beseeching, or even anger. And while birth-related prayers naturally are directed at the safety of the newborn, they also embrace all of the individuals present, whether a tiny family, a single individual, or an entire community.

The Long-life Ceremony of the Jicarilla Apache

Many of the ceremonies that native peoples perform at birth recognize, either explicitly or symbolically, that babies face many risks and that many children die during infancy. The Jicarilla Apache, who now live in north-central New Mexico but once roamed a much larger territory, note this in their cosmology, or religious beliefs. They believe that their people emerged from the underground, a peaceful, idyllic world where rituals were unnecessary because there were no diseases or other troubles. When that world began to die, they chose to move into the next world, which brought them here, onto the earth, with its attendant dangers. As they emerged, the gods gave them the Long-life Ceremony for protection. This ceremony, handed down over many years, is one of their most ancient traditions, imbued with special significance.

The native name for the Long-life Ceremony has been translated to mean "Water Has Been Put on Top of His Head." This practice blesses and strengthens the infant, much like an early Christian baptism. It takes place as soon as possible after birth, before anything untoward can happen. As practiced by Apache holy people, the paternal elders, or the parents themselves, it is meant to carry the child safely until the puberty ceremony. What actually occurs is highly personal and variable, depending on the families and circumstances, but it usually involves lightly touching sacred water and cornmeal to the baby's head while uttering special prayers.

The Omaha Ceremony of Turning the Child After the First Thunder

Other tribes recognize a birth more publicly and perform rituals connected to healing in the broadest sense. They call in all the help they can to bless the baby and strengthen his journey on the path of life. For example, on the eighth day of life the Omaha ceremonially announced a newborn's birth to the universal entities, uniting his life force with all of nature. Their petitions sought safe passage for each infant as he traveled the four hills, which for the Omaha symbolized life's major stages of infancy, childhood, adulthood, and old age.

Today many Omaha traditional families continue this ritual or perform similar ceremonies that have evolved from it.

As the infant grows, the Omaha perform another ritual that formally introduces her to the tribe and recognizes her as a member. This rite, which is called Turning the Child, takes place in the spring after the first thunders have come. It includes all children who are nearly ready to walk alone. The barefoot child stands on a symbolic stone; as the family and other tribal members sing prayers and songs, they put new moccasins, blessed with sacred herbs, on her feet and help her take four steps. Symbolically she has been "sent into the midst of the winds," commemorating that she has made it through infancy and into childhood. Her baby name is thrown away, and a new name is announced to all of nature and to the crowd of people who have gathered for the occasion.

The new moccasins the child receives at the Turning the Child ritual have a small hole cut into one of the soles. According to the Omaha physician La Fleshe, this is a way of preventing the child's death: If a messenger from the spirit world comes to snatch the baby, the child can say, "I cannot go on a journey because my moccasins are worn out."

Traditionally, the Abenaki and certain other Eastern tribes also leave a tiny hole in the moccasins they fashion for each young child, but its purpose is different. If a messenger from the spirit world comes to invite the child back over, this symbolic hole allows the tiny spirit to slip out of the body if it so desires. Among these peoples, there has always been an implicit understanding that if a child's spirit does not wish to remain on earth, it should be blessed and allowed to depart.

The Navajo First Smile Ceremony

Not everything that happens at birth is invested with such gravity. Among the Navajo, the First Smile Ceremony, a short, private ritual that occurs shortly after a child is born, reveals a lighter, more humorous sensibility. The maternal grandmother usually does the honors, but another female relative attending the birth, the midwife, or the mother herself can carry it out. Holding the newborn child, she strokes its face with a finger or a little feather, teasing the baby to get it to smile and bring its soul to mirth. The Navajo seize on this fleeting moment, acknowledging the smile as a sign of blessing and a reassurance of a long, happy life.

A bit later the Navajo also honor the first laugh. Their understanding is that the person who first gets the infant to laugh wins the honor of preparing a big feast for the little one. Frequently this is a person who plays an important role in the child's life.

It may be that some little root of the Sacred Tree still lives. Nourish it then, that it may leaf and bloom and fill with singing birds. Hear me, not for myself, but for my people; I am old. Hear me that they may once more go back into the sacred hoop and find the Good Red Road, the shielding tree.

--Black Elk, Oglala Sioux holy man and medicine man

This book explores the healing arts of American Indians. Our native tribes had and still perform a dazzling array of healing rituals; they also know and use hundreds of herbs, fungi, lichens, and other natural materials. Although many of these practices are ancient, they remain vital. Today healers from all over the world--Europe, Australia, India, and China--come to the United States to learn how to use our native medicinal plants. But ironically, many Americans have not yet tapped into this distinctively American tradition, instead choosing European herbal medicine, homeopathy, or acupuncture in their quest for alternatives to conventional medical treatment.

But American Indian healing goes well beyond treating disease. As we approach the end of the twentieth century it offers a rich resource for people who want to connect, both collectively and individually, with their spiritual selves. Throughout their sweeping history, American Indians have held the spiritual side of life to be primary and sacred. Their belief system provides them with a deep and nurturing connection to the earth and the spiritual realm.

Birth and Infancy: "Thank You For Coming To Our Village"

When a new baby is born among the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Clan Mothers welcome the newborn by saying: "Thank you for coming to our village; we hope you will stay with us."

--Katsi Cook, Mohawk midwife from Akwesasne and a research fellow in the American Indian Program at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York

The cry of a newborn child is music to which all people respond. American Indians place special emphasis on welcoming a child not only into the family but also into the tribe and the world. When a baby is born, he emerges from his mother's womb into the womb of Mother Earth.

Of course, childbirth was not always such a smooth transition. In early societies women frequently gave birth outside the village in less-than-ideal or even dangerous situations. Often they were alone and exposed to the elements. But most American Indian women were well equipped to manage within their environments. They were in vigorous good health and quite fit throughout their pregnancies, so that birthing was fairly spontaneous and without much trauma or pause from their normal work. Early records tell of women giving birth in challenging circumstances and then walking great distances with their newborns on their backs.

But not every birth was comfortable or successful. Infant deaths and abnormalities occurred, and mothers died in childbirth or of infections or complications immediately after giving birth.

Across the continent, as native people settled into village life they developed a broad array of ceremonies, rituals, prayers, and special herbs and medicines to protect and sanctify this important life passage. Each tribe used its own sequence of prayers and offerings of sacred substances to ease labor and delivery for the mother and help ensure the infant's survival.

Today, as long as there are no complications, many American Indian mothers choose to give birth at home or in specially prepared family settings. Birthing outside of the hospital allows women to continue to honor their traditional tribal rituals. But even hospital birth need not impede some of the smaller, more private ceremonies. And because some rites take place before labor begins as well as after the baby arrives at home, many people can avail themselves of these special blessings.

In some tribes, rituals for the birth mother begin just before or during labor and delivery. Among the Diné or Navajo, for example, a woman can request that a Blessing Way, or "No Sleep," be done for her before she leaves for the hospital or as she prepares for the birth at home. The name "No Sleep" means a one-night sing; it is much like a vigil. The medicine man sings for her from late evening until "the dawn has a white stripe" in order to ensure that her labor and delivery will be normal and as easy as possible, and that her baby will be healthy and whole.

Birthing practices during and immediately after the birth frequently combine the sacred and the practical. Often part of the midwife's work during labor is to sing to and massage the laboring woman, bathe her in healing herbs, and ritually wash her abdomen, breasts, arms, and legs. In many cultures women do this for themselves, continuing a practice they began during the latter part of pregnancy. The midwife uses sacred herbs and important herbs of childbearing such as sweetgrass, hawthorn berries, or leaves of raspberry, strawberry, bearberry, or juniper submerged in either river or lake water. Not only do these herbs bless the process, they also relax the mother, ease the delivery, and nurture a pure, strong spirit in the baby. In some tribes midwives use other mild herbs, such as blue cohosh root, to gently speed the birth.

After the delivery, the focus is on the baby. A birth attendant ritually bathes the baby in a sacred herbal wash. Relatives may look the infant over for any unusual markings or other signs. For example, among the Delaware, knowledgeable elders read a birthmark as a special sign that means--depending on its size and configuration--good luck or a long life. Sometimes the mark may be attributed to the mother's or father's dream; in other cases it is an indication that either or both parents experienced difficulties with other people.

On occasion family members attending the birth may see an ancient wisdom in the infant's eyes or recognize the soul of an ancestor. In special instances it becomes clear at birth--or sometimes even before--that this particular baby has been blessed and summoned to a specific calling. In the past, a boy might have been dedicated to the path of a great warrior or directed to follow a favored uncle into a secret society. A girl infant might be consecrated to fertility, to skill in tanning, or to the mineral, animal, herbal, and fungal wisdom of the earth.

Families, especially those suffering from the previous loss of one or more children, feel a special urgency about strengthening a just-born member of the family in this way. Many Indian children rebel against this idea, refusing to follow the life path that the tribe has chosen for them. But there are amazing stories of individuals who eventually come around to occupy the roles envisioned for them at birth.

Spiderwebs, the Earliest Dream Catchers

Today's popular dream catchers have their roots in ancient amulets called spiderwebs. Loving family members--parents, aunts, uncles, and siblings--created these graceful ephemeral designs of quill and beadwork on hide. The spiderweb, which can also be seen on early birch-bark scrolls, was a charm meant to hold good energy. And like a true spiderweb, this one could catch everything, especially harm coming from the spirit world or anywhere else, before it reached the baby.

The Great Lakes Algonquian and the Cree of Canada and the central United States were particularly likely to use these charms, whose designs were echoed on the blankets and clothing of the infant. Today these powerful talismans have come to be called dream catchers.

Welcoming a new child does not always involve elaborate ceremony. Paula Dove Jennings, of the Turtle Clan, is a Niantic-Narragansett oral historian. Among her people, traditions center on women. Growing up in Charlestown, Rhode Island, she recalls being told that when she was born, on July 3, 1940--the first daughter of Pretty Flower and Roaring Bull--her father walked out onto their street, raised his arms, and shouted, "Now I am a man!" to celebrate her birth. Her older brother, Red Earth, was a well-loved toddler, yet the importance of having a girl had to be publicly proclaimed.

Sometimes a rite is a small but significant act, such as the sprinkling of sacred cornmeal. Quiet prayers and other private practices, such as making a medicine bundle, dream catcher, or other special amulet, are sometimes all that are needed to work a bit of magic.

For example, Kwakiutl mothers, who live on the Northwest Coast of the United States, perform the Girl Child Prosperity Ceremony so that their baby girls grow to be healthy, industrious, and accomplished women. After preparing special birth amulets, which her infant daughter will wear or carry close until she is nine months old, the mother prays: "O, supernatural power of the Supernatural One of the Rocks, go on, look at what I am doing to you, for I pray you to take mercy on my child and, please, let her be successful in getting property and let nothing evil happen to her when she goes up the mountain picking all kinds of berries; and, please, protect her, Supernatural One."

American Indians weave prayers--large and small--into many aspects of their lives. This is especially true when it comes to the rituals, ceremonies, and other symbolic events that mark passages through an individual's life. Each tribe and culture group has its own unique way of praying. While a great deal has changed because of Christian influences and missionaries' work over the past five hundred years, the strongest traditions are still alive.

Prayers are usually long, melodic, and haunting. They are frequently offered to the sky, the Creator, and the universe. Many prayers use one or more of the most highly valued sacred substances--tobacco, cornmeal, pollen, bearberry, sweetgrass, sage, and cedar. Prayers unite the finest tribal traditions and beliefs with an individual's most personal feelings. The supplicant speaks, cries, or sings the prayer, shouting or loudly emphasizing certain parts. Many prayers are filled with earnest tears of sadness, love, beseeching, or even anger. And while birth-related prayers naturally are directed at the safety of the newborn, they also embrace all of the individuals present, whether a tiny family, a single individual, or an entire community.

The Long-life Ceremony of the Jicarilla Apache

Many of the ceremonies that native peoples perform at birth recognize, either explicitly or symbolically, that babies face many risks and that many children die during infancy. The Jicarilla Apache, who now live in north-central New Mexico but once roamed a much larger territory, note this in their cosmology, or religious beliefs. They believe that their people emerged from the underground, a peaceful, idyllic world where rituals were unnecessary because there were no diseases or other troubles. When that world began to die, they chose to move into the next world, which brought them here, onto the earth, with its attendant dangers. As they emerged, the gods gave them the Long-life Ceremony for protection. This ceremony, handed down over many years, is one of their most ancient traditions, imbued with special significance.

The native name for the Long-life Ceremony has been translated to mean "Water Has Been Put on Top of His Head." This practice blesses and strengthens the infant, much like an early Christian baptism. It takes place as soon as possible after birth, before anything untoward can happen. As practiced by Apache holy people, the paternal elders, or the parents themselves, it is meant to carry the child safely until the puberty ceremony. What actually occurs is highly personal and variable, depending on the families and circumstances, but it usually involves lightly touching sacred water and cornmeal to the baby's head while uttering special prayers.

The Omaha Ceremony of Turning the Child After the First Thunder

Other tribes recognize a birth more publicly and perform rituals connected to healing in the broadest sense. They call in all the help they can to bless the baby and strengthen his journey on the path of life. For example, on the eighth day of life the Omaha ceremonially announced a newborn's birth to the universal entities, uniting his life force with all of nature. Their petitions sought safe passage for each infant as he traveled the four hills, which for the Omaha symbolized life's major stages of infancy, childhood, adulthood, and old age.

Today many Omaha traditional families continue this ritual or perform similar ceremonies that have evolved from it.

As the infant grows, the Omaha perform another ritual that formally introduces her to the tribe and recognizes her as a member. This rite, which is called Turning the Child, takes place in the spring after the first thunders have come. It includes all children who are nearly ready to walk alone. The barefoot child stands on a symbolic stone; as the family and other tribal members sing prayers and songs, they put new moccasins, blessed with sacred herbs, on her feet and help her take four steps. Symbolically she has been "sent into the midst of the winds," commemorating that she has made it through infancy and into childhood. Her baby name is thrown away, and a new name is announced to all of nature and to the crowd of people who have gathered for the occasion.

The new moccasins the child receives at the Turning the Child ritual have a small hole cut into one of the soles. According to the Omaha physician La Fleshe, this is a way of preventing the child's death: If a messenger from the spirit world comes to snatch the baby, the child can say, "I cannot go on a journey because my moccasins are worn out."

Traditionally, the Abenaki and certain other Eastern tribes also leave a tiny hole in the moccasins they fashion for each young child, but its purpose is different. If a messenger from the spirit world comes to invite the child back over, this symbolic hole allows the tiny spirit to slip out of the body if it so desires. Among these peoples, there has always been an implicit understanding that if a child's spirit does not wish to remain on earth, it should be blessed and allowed to depart.

The Navajo First Smile Ceremony

Not everything that happens at birth is invested with such gravity. Among the Navajo, the First Smile Ceremony, a short, private ritual that occurs shortly after a child is born, reveals a lighter, more humorous sensibility. The maternal grandmother usually does the honors, but another female relative attending the birth, the midwife, or the mother herself can carry it out. Holding the newborn child, she strokes its face with a finger or a little feather, teasing the baby to get it to smile and bring its soul to mirth. The Navajo seize on this fleeting moment, acknowledging the smile as a sign of blessing and a reassurance of a long, happy life.

A bit later the Navajo also honor the first laugh. Their understanding is that the person who first gets the infant to laugh wins the honor of preparing a big feast for the little one. Frequently this is a person who plays an important role in the child's life.

Recenzii

"A tapestry of stories, prayers, legends, myths, and herbal traditions that shows the oneness of all humanity and echoes the familiar patterns of American Indian culture from Alaska to Brazil. This book will become a standard reference."

--Rosita Arvigo, D.N., author of Sastun: My Apprenticeship with a Maya Healer

"A book of charm and substance: a literal teach-yourself volume on American Indian healing arts."

--Thomas E. Lovejoy, Counselor to the Secretary for Biodiversity and Environmental Affairs, Smithsonian Institution

--Rosita Arvigo, D.N., author of Sastun: My Apprenticeship with a Maya Healer

"A book of charm and substance: a literal teach-yourself volume on American Indian healing arts."

--Thomas E. Lovejoy, Counselor to the Secretary for Biodiversity and Environmental Affairs, Smithsonian Institution

Descriere

One of the most complete and authentic books available on Native American healing traditions, with dozens of natural remedies for everyday use. Illustrated.