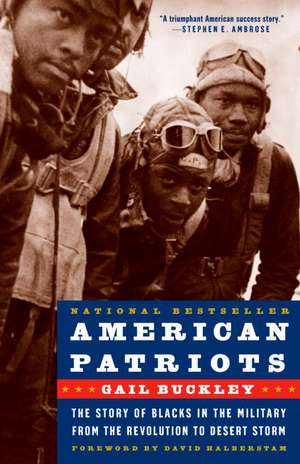

American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm

Autor Gail Lumet Buckley David Halberstam Editat de Tonya Boldenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2002 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Black Caucus of the American Library Association Literary_award (2002), Robert F. Kennedy Book Award (2002)

Preț: 156.21 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 234

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.89€ • 32.46$ • 25.11£

29.89€ • 32.46$ • 25.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375760099

ISBN-10: 0375760091

Pagini: 608

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375760091

Pagini: 608

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Gail Lumet Buckley is a journalist and the daughter of Lena Horne. Her family history — The Hornes — became an American Masters documentary, and she narrated a documentary on black American families for PBS. She has written for the Los Angeles Times, Vogue, the New York Daily News, and The New York Times. She lives in New York.

Extras

1

The Revolution

slavery and independence

I served in the Revolution, in General Washington's army. . . . I have stood in battle, where balls, like hail, were flying all around me. The man standing next to me was shot by my side-his blood spouted upon my clothes, which I wore for weeks. My nearest blood, except that which runs in my veins, was shed for liberty. My only brother was shot dead instantly in the Revolution. Liberty is dear to my heart-I cannot endure the thought, that my countrymen should be slaves.

-"Dr. Harris," a black Revolutionary veteran, in an address to the Congregational and Presbyterian Anti-Slavery Society of Francestown, New Hampshire, 1842

Crispus Attucks: The First Martyr of the Revolution

BLOODY MASSACRE," screamed the March 12, 1770, issue of the Massachusetts Gazette, Paul Revere's four-color illustrated broadsheet, depicting redcoats with muskets firing into a crowd of well-dressed Boston citizens. Four victims lie bloodied on the ground. One, closest to the soldiers, the only one dressed in rough seaman clothes instead of a waistcoat and three-cornered hat, lies in the center foreground in a pool of blood. "The unhappy Sufferers," Revere wrote, were "Sam'l Gray, Sam'l Maverick, James Caldwell, Crispus Attucks Killed." (Revere omitted Patrick Carr, an Irish leather worker, who was also killed.) Gray was a rope maker, Maverick an apprentice joiner, Caldwell a ship's mate; the seaman Attucks, "killed on the Spot, two Balls entering his Breast," was described as "born in Framingham, but lately belonging to New Providence [the Bahamas]." The victims would lie in state in Faneuil Hall. "All the Bells tolled a solemn Peal" when they were buried together in one vault "in the middle burying-ground."2

Calling himself Michael Johnson, Attucks, the son of an African father and a Massachusetts Natick Indian mother, had spent the past twenty years at sea, having run away to escape slavery.3 Ten pounds' reward had been offered in 1750 by Deacon William Brown of Framingham for the return of "a Molatto Fellow, about 27 years of age, named Crispas, 6 Feet two Inches high, short, curl'd Hair, his Knees nearer together than common: had on a light colour'd Bearskin coat."4 In port in Boston on the night of March 5, 1770, Attucks was in a King Street tavern when an alarm bell was heard from the street's British sentry. When, leading a stick- and bat-wielding gang from the tavern, he discovered that the sentry was under "attack" only from snowball-throwing boys, he and his mob immediately took the side of the boys against the "Lobster Backs"-using heavy sticks instead of snowballs. Witnesses said that Attucks, striking the first blow, caused arriving British soldiers to open fire and hit eleven civilians-five of whom, including Attucks, were killed.

At the cost of public scorn (and to cover up his cousin Samuel Adams's role in inciting riots), the Boston lawyer John Adams, a radical "Son of Liberty" who disapproved of violence, defended the British soldiers. Contradicting Paul Revere's presentation of the dead as respectable Bostonians, Adams declared that Attucks had been the leader of a "motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs."5 The merchant John Hancock also accused Attucks of provoking the so-called "Boston Massacre," but from a different point of view. "Who set the example of guns?" Hancock asked later. "Who taught the British soldier that he might be defeated? Who dared look into his eyes? I place, therefore, this Crispus Attucks in the foremost rank of the men that dared."6 The British soldiers were acquitted, but Americans won the propaganda battle. Attucks and his companions became the first popular martyrs of the Revolution.

"You will hear from Us with Astonishment," read an anonymous letter to Governor Thomas Hutchinson in 1773, which John Adams copied in his diary. "You ought to hear from Us with Horror. You are chargeable before God and Man, with our Blood- The Soldiers were but passive Instruments. . . . You acted, cooly, deliberately, with all that premeditated Malice, not against Us in particular but against the People in general. . . . You will hear further from us hereafter."7 It was signed "Crispus Attucks"-a new symbol of resistance.

O O O

On the eve of the Revolution, the black population of the British North American colonies was 500,000, out of a total population of 2,600,000.8 Only a fraction of that population went to war. Some five thousand blacks served under George Washington, and about a thousand, mostly Southern runaways, fought for George III.9 Although the percentage of the black population who served was small, by 1779 as many as one in seven members of Washington's never very large army were black. According to the historian Thomas Fleming, the Continental Line was "more integrated than any American force except the armies that fought in the Vietnam and Gulf Wars."10

The Great American "Fig Tree"

At the end of the French and Indian Wars, Britain controlled North America from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, as well as most of the West Indies. It had reached the zenith of its empire just as the colonies were beginning to have a sense of nationhood. "Cast your eyes with me a little over this globe to view the deplorable state of your fellow creatures in other countries," wrote the Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson in 1768. "In Russia, Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and many parts of Germany there is no such thing as free-holders. . . . But how different is the case amongst us. We enjoy an unprecarious property, and every man may freely taste the fruits of his own labors under his vine and under his fig tree."11

The debt Britain had incurred in the Seven Years' War ensured taxation of the colonies and threatened life under the idyllic American fig tree. In British eyes, the American colonies existed only for the benefit of the mother country, but Americans saw any form of taxation as slavery. New England's objections to the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and all the other unpopular acts fueled the fires of independence. John Adams and his failed businessman cousin Samuel, leading radicals in the Continental Congress, were outspoken "Sons of Liberty," a term coined in the British Parliament in 1765 to describe American Stamp Act protestors. Samuel Adams created the Committees of Correspondence, an underground movement with branches springing up throughout New England, to encourage resistance against the British.

The fires of independence were fueled among blacks as well as whites. A Massachusetts petition of 1773 from "a Grate Number of Blacks . . . who . . . are held in a state of slavery within the bowels of a free and Christian Country" asked for freedom and "some part of the unimproved land, belonging to the province, for a settlement, that each of us may there sit down quietly under his own fig tree."12

Quaker Philadelphia was the heart of early eighteenth-century abolitionism. Massachusetts Puritans preached against slavery, but only Quakers argued for justice and equality for blacks on every level of life. In 1727, the twenty-one-year-old Philadelphia printer Benjamin Franklin started a discussion group, the Junto, in which antislavery ideals figured large. Two years later he printed, anonymously, the first of his many antislavery tracts. "A Caution and a Warning to Great Britain and Her Colonies," a pamphlet published in 1766 by a Philadelphia Quaker named Anthony Benezet, was widely circulated. "How many of those who distinguish themselves as Advocates of Liberty remain insensible," he wrote, "to the treatment of thousands and tens of thousands of our fellow men, who . . . are at this very time kept in the most deplorable state of slavery." Meanwhile, Boston's James Otis, another outspoken opponent of Britain's "Intolerable Acts," wrote: "The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed are all men, white or black."

The upper South seemed to agree with the North that slavery would eventually be abandoned, and in the meantime ameliorated. In 1762, George Washington told his new overseer to "take all necessary and proper care of the Negroes, using them with proper humanity and discretion."13 Young Thomas Jefferson's first legislative action in the 1769 Virginia House of Burgesses was an emancipation measure.14 With so many important advocates, many believed that the new American nation would be free.

Slavery was abolished in the British Isles in 1772. The decision resulted from the suit of one slave, James Somerset, who ran away from his American master in England. Somerset's lawyer, the British abolitionist Granville Sharp, won the case by arguing that since no positive law creating slavery existed in England, it could not be practiced there. Three days after the judgment, a group of two hundred blacks "with their ladies" held a public entertainment in Westminster "to celebrate the triumph of their Brother Somerset."15 British emancipation was a major propaganda coup, but it freed only the twenty thousand-odd slaves living in Britain itself, leaving American and West Indian slavery untouched. Benjamin Franklin wrote to Anthony Benezet about the "hypocrisy" of Britain "for promoting the Guinea trade, while it piqued itself on its virtue . . . in setting free a single Negro."16

By 1774, Boston-whose port was closed until the eighteen thousand pounds of tea dumped in the harbor the previous December was paid for-was the center of abolition as well as revolution. "No country can be called free when there is one slave," wrote James Swan, a Boston merchant and Son of Liberty who had disguised himself as an Indian in the Boston Tea Party.17 "It has always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me," Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, "to fight for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have."18

In November 1774, the thirty-seven-year-old Tom Paine arrived in Philadelphia with a letter of introduction to Benjamin Franklin. Paine, a former corsetmaker's apprentice and low-level tax collector, was drawn to abolition as much by his sympathy for antigovernment politics as by his Quaker background. Franklin helped Paine become editor of The Pennsylvania Magazine, where his first published article, "African Slavery in America," appeared on March 8, 1775. "With what consistency, or decency," he wrote, could colonists "complain so loudly of attempts to enslave them, while they hold so many hundred thousand in slavery."19 Paine advocated abolition, land redistribution, and economic opportunity. Two weeks later Patrick Henry, a slave owner who called slavery "repugnant to humanity," raised the American battle cry with "Give me liberty or give me death!" America's first antislavery society met in Philadelphia on April 14, 1775. Five days later, America was at war with Britain.

Lexington and Concord

New England towns and villages had been preparing for war since the winter of 1774. Weapons and gunpowder were stored and militia and Minutemen (an elite militia in existence only since the Boston Tea Party) were armed and ready. The war began in Massachusetts, where the British were greatly outnumbered.

Boston's ever more rebellious population outnumbered Governor Thomas Gage's troops by a factor of four, and his request for more men had been rejected. In April 1775, British intelligence learned that a secret meeting in Concord of the illegal Massachusetts Congress had determined to establish an army to fight the Crown. On April 18, Gage ordered troops, under Colonel Francis Smith, to proceed to Concord to seize all weapons and ammunition as Major John Pitcairn, Smith's second in command, led an advance guard to Lexington.

American wife was supplying information to Dr. Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams's closest associate on Boston's Committee of Correspondence.20) As British soldiers left by boat across Back Bay late on the night of April 18, the Committee of Correspondence dispatch rider Paul Revere, under instructions from Warren, hung two signal lamps ("One if by land, two if by sea") in the steeple of the Old North Church. Then, having been silently rowed across the Charles under the guns of a British man-of-war, he mounted one of the fastest horses in the colony, to warn first Lexington (where Samuel Adams and John Hancock were distancing themselves from Boston and possible arrest) and then Concord that the British were coming. In Lexington, Revere, joined by another Committee of Correspondence dispatch rider, was briefly stopped by a British patrol. After supplying "information" (with a gun to his head), the printer-silversmith-revolutionary and his partner managed to break away by galloping off in opposite directions. Armed with Revere's "information," the British patrol rode back to say that at least five hundred Minutemen were waiting on Lexington Green. The several hundred British soldiers who approached the green early the next morning were probably surprised to find a motley army of seventy-seven, including boys, old men, and a slave.21

Ordering British troops not to fire, Pitcairn told the Americans to drop their weapons and disperse. Lexington's militia, led by Captain John Parker, a farmer and a veteran of the French and Indian Wars, was not eager for battle, either. But just as Parker gave the order to withdraw, a musket (American or British) flashed in the pan. There were now scattered shots from both sides. Eight Americans died and nine were wounded before the firing stopped. "O what a glorious morning is this!" said Samuel Adams, hearing the guns from his refuge near Lexington.

Prince Estabrook, a Lexington slave and member of Captain Parker's company, was one of the Americans who fought on Lexington Green that first morning of the Revolution. Later in the day other black militiamen from neighboring towns met the British at Concord, Arlington, Lincoln, and points on the road back to Boston.

According to the historian Howard Peckham, the Battle of Lexington lasted about fifteen minutes and the Battle of Concord lasted about five.22 Entering Concord without resistance at around eight a.m., Smith's men found some four hundred Minutemen waiting at North Bridge, including the Reverend William Emerson, whose grandson Ralph Waldo Emerson would write of the "rude bridge" and the "shot heard round the world." In Concord, the British fired first. Three British and two Americans were killed before the Americans retreated. Prince Estabrook, veteran of Lexington, was wounded. He was listed on the official roster of "Provincials" killed or wounded at Concord as "a Negro man"-the only victim not called "Mr."23 The American casualties were 41 wounded and 49 dead. The British counted 73 dead, 174 wounded, and 26 missing.24

There were other black militiamen defending North Bridge: Peter Salem of Framingham, who had been freed to enlist; Samuel Craft, of Newton; Caesar Ferrit and his son John, of Natick; Pompy, of Braintree; Pomp Blackman; and Prince, of Brookline (the slave of Joshua Boylston).25 The twenty-two-year-old Lemuel Haynes had marched all the way to Concord with his Connecticut militia regiment.

Haynes had just missed Lexington: his company was en route from Granville, Connecticut, when the battle broke out. But he made it to Concord, and shortly after the battle the "former indentured servant and patriot versus bruit Tyranny" wrote a poem, "The inhuman tragedy perpetrated 19th of April 1775 by a number of the British Troops under the command of Thomas Gage," signed "Lemuel a Young Mollato": "For Liberty, each Freeman Strives / As its a gift of God / And for it willing yield their Lives . . . Much better there, in Death Confin'd / than a Surviving Slave."26

The Revolution

slavery and independence

I served in the Revolution, in General Washington's army. . . . I have stood in battle, where balls, like hail, were flying all around me. The man standing next to me was shot by my side-his blood spouted upon my clothes, which I wore for weeks. My nearest blood, except that which runs in my veins, was shed for liberty. My only brother was shot dead instantly in the Revolution. Liberty is dear to my heart-I cannot endure the thought, that my countrymen should be slaves.

-"Dr. Harris," a black Revolutionary veteran, in an address to the Congregational and Presbyterian Anti-Slavery Society of Francestown, New Hampshire, 1842

Crispus Attucks: The First Martyr of the Revolution

BLOODY MASSACRE," screamed the March 12, 1770, issue of the Massachusetts Gazette, Paul Revere's four-color illustrated broadsheet, depicting redcoats with muskets firing into a crowd of well-dressed Boston citizens. Four victims lie bloodied on the ground. One, closest to the soldiers, the only one dressed in rough seaman clothes instead of a waistcoat and three-cornered hat, lies in the center foreground in a pool of blood. "The unhappy Sufferers," Revere wrote, were "Sam'l Gray, Sam'l Maverick, James Caldwell, Crispus Attucks Killed." (Revere omitted Patrick Carr, an Irish leather worker, who was also killed.) Gray was a rope maker, Maverick an apprentice joiner, Caldwell a ship's mate; the seaman Attucks, "killed on the Spot, two Balls entering his Breast," was described as "born in Framingham, but lately belonging to New Providence [the Bahamas]." The victims would lie in state in Faneuil Hall. "All the Bells tolled a solemn Peal" when they were buried together in one vault "in the middle burying-ground."2

Calling himself Michael Johnson, Attucks, the son of an African father and a Massachusetts Natick Indian mother, had spent the past twenty years at sea, having run away to escape slavery.3 Ten pounds' reward had been offered in 1750 by Deacon William Brown of Framingham for the return of "a Molatto Fellow, about 27 years of age, named Crispas, 6 Feet two Inches high, short, curl'd Hair, his Knees nearer together than common: had on a light colour'd Bearskin coat."4 In port in Boston on the night of March 5, 1770, Attucks was in a King Street tavern when an alarm bell was heard from the street's British sentry. When, leading a stick- and bat-wielding gang from the tavern, he discovered that the sentry was under "attack" only from snowball-throwing boys, he and his mob immediately took the side of the boys against the "Lobster Backs"-using heavy sticks instead of snowballs. Witnesses said that Attucks, striking the first blow, caused arriving British soldiers to open fire and hit eleven civilians-five of whom, including Attucks, were killed.

At the cost of public scorn (and to cover up his cousin Samuel Adams's role in inciting riots), the Boston lawyer John Adams, a radical "Son of Liberty" who disapproved of violence, defended the British soldiers. Contradicting Paul Revere's presentation of the dead as respectable Bostonians, Adams declared that Attucks had been the leader of a "motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs."5 The merchant John Hancock also accused Attucks of provoking the so-called "Boston Massacre," but from a different point of view. "Who set the example of guns?" Hancock asked later. "Who taught the British soldier that he might be defeated? Who dared look into his eyes? I place, therefore, this Crispus Attucks in the foremost rank of the men that dared."6 The British soldiers were acquitted, but Americans won the propaganda battle. Attucks and his companions became the first popular martyrs of the Revolution.

"You will hear from Us with Astonishment," read an anonymous letter to Governor Thomas Hutchinson in 1773, which John Adams copied in his diary. "You ought to hear from Us with Horror. You are chargeable before God and Man, with our Blood- The Soldiers were but passive Instruments. . . . You acted, cooly, deliberately, with all that premeditated Malice, not against Us in particular but against the People in general. . . . You will hear further from us hereafter."7 It was signed "Crispus Attucks"-a new symbol of resistance.

O O O

On the eve of the Revolution, the black population of the British North American colonies was 500,000, out of a total population of 2,600,000.8 Only a fraction of that population went to war. Some five thousand blacks served under George Washington, and about a thousand, mostly Southern runaways, fought for George III.9 Although the percentage of the black population who served was small, by 1779 as many as one in seven members of Washington's never very large army were black. According to the historian Thomas Fleming, the Continental Line was "more integrated than any American force except the armies that fought in the Vietnam and Gulf Wars."10

The Great American "Fig Tree"

At the end of the French and Indian Wars, Britain controlled North America from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, as well as most of the West Indies. It had reached the zenith of its empire just as the colonies were beginning to have a sense of nationhood. "Cast your eyes with me a little over this globe to view the deplorable state of your fellow creatures in other countries," wrote the Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson in 1768. "In Russia, Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and many parts of Germany there is no such thing as free-holders. . . . But how different is the case amongst us. We enjoy an unprecarious property, and every man may freely taste the fruits of his own labors under his vine and under his fig tree."11

The debt Britain had incurred in the Seven Years' War ensured taxation of the colonies and threatened life under the idyllic American fig tree. In British eyes, the American colonies existed only for the benefit of the mother country, but Americans saw any form of taxation as slavery. New England's objections to the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and all the other unpopular acts fueled the fires of independence. John Adams and his failed businessman cousin Samuel, leading radicals in the Continental Congress, were outspoken "Sons of Liberty," a term coined in the British Parliament in 1765 to describe American Stamp Act protestors. Samuel Adams created the Committees of Correspondence, an underground movement with branches springing up throughout New England, to encourage resistance against the British.

The fires of independence were fueled among blacks as well as whites. A Massachusetts petition of 1773 from "a Grate Number of Blacks . . . who . . . are held in a state of slavery within the bowels of a free and Christian Country" asked for freedom and "some part of the unimproved land, belonging to the province, for a settlement, that each of us may there sit down quietly under his own fig tree."12

Quaker Philadelphia was the heart of early eighteenth-century abolitionism. Massachusetts Puritans preached against slavery, but only Quakers argued for justice and equality for blacks on every level of life. In 1727, the twenty-one-year-old Philadelphia printer Benjamin Franklin started a discussion group, the Junto, in which antislavery ideals figured large. Two years later he printed, anonymously, the first of his many antislavery tracts. "A Caution and a Warning to Great Britain and Her Colonies," a pamphlet published in 1766 by a Philadelphia Quaker named Anthony Benezet, was widely circulated. "How many of those who distinguish themselves as Advocates of Liberty remain insensible," he wrote, "to the treatment of thousands and tens of thousands of our fellow men, who . . . are at this very time kept in the most deplorable state of slavery." Meanwhile, Boston's James Otis, another outspoken opponent of Britain's "Intolerable Acts," wrote: "The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed are all men, white or black."

The upper South seemed to agree with the North that slavery would eventually be abandoned, and in the meantime ameliorated. In 1762, George Washington told his new overseer to "take all necessary and proper care of the Negroes, using them with proper humanity and discretion."13 Young Thomas Jefferson's first legislative action in the 1769 Virginia House of Burgesses was an emancipation measure.14 With so many important advocates, many believed that the new American nation would be free.

Slavery was abolished in the British Isles in 1772. The decision resulted from the suit of one slave, James Somerset, who ran away from his American master in England. Somerset's lawyer, the British abolitionist Granville Sharp, won the case by arguing that since no positive law creating slavery existed in England, it could not be practiced there. Three days after the judgment, a group of two hundred blacks "with their ladies" held a public entertainment in Westminster "to celebrate the triumph of their Brother Somerset."15 British emancipation was a major propaganda coup, but it freed only the twenty thousand-odd slaves living in Britain itself, leaving American and West Indian slavery untouched. Benjamin Franklin wrote to Anthony Benezet about the "hypocrisy" of Britain "for promoting the Guinea trade, while it piqued itself on its virtue . . . in setting free a single Negro."16

By 1774, Boston-whose port was closed until the eighteen thousand pounds of tea dumped in the harbor the previous December was paid for-was the center of abolition as well as revolution. "No country can be called free when there is one slave," wrote James Swan, a Boston merchant and Son of Liberty who had disguised himself as an Indian in the Boston Tea Party.17 "It has always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me," Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, "to fight for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have."18

In November 1774, the thirty-seven-year-old Tom Paine arrived in Philadelphia with a letter of introduction to Benjamin Franklin. Paine, a former corsetmaker's apprentice and low-level tax collector, was drawn to abolition as much by his sympathy for antigovernment politics as by his Quaker background. Franklin helped Paine become editor of The Pennsylvania Magazine, where his first published article, "African Slavery in America," appeared on March 8, 1775. "With what consistency, or decency," he wrote, could colonists "complain so loudly of attempts to enslave them, while they hold so many hundred thousand in slavery."19 Paine advocated abolition, land redistribution, and economic opportunity. Two weeks later Patrick Henry, a slave owner who called slavery "repugnant to humanity," raised the American battle cry with "Give me liberty or give me death!" America's first antislavery society met in Philadelphia on April 14, 1775. Five days later, America was at war with Britain.

Lexington and Concord

New England towns and villages had been preparing for war since the winter of 1774. Weapons and gunpowder were stored and militia and Minutemen (an elite militia in existence only since the Boston Tea Party) were armed and ready. The war began in Massachusetts, where the British were greatly outnumbered.

Boston's ever more rebellious population outnumbered Governor Thomas Gage's troops by a factor of four, and his request for more men had been rejected. In April 1775, British intelligence learned that a secret meeting in Concord of the illegal Massachusetts Congress had determined to establish an army to fight the Crown. On April 18, Gage ordered troops, under Colonel Francis Smith, to proceed to Concord to seize all weapons and ammunition as Major John Pitcairn, Smith's second in command, led an advance guard to Lexington.

American wife was supplying information to Dr. Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams's closest associate on Boston's Committee of Correspondence.20) As British soldiers left by boat across Back Bay late on the night of April 18, the Committee of Correspondence dispatch rider Paul Revere, under instructions from Warren, hung two signal lamps ("One if by land, two if by sea") in the steeple of the Old North Church. Then, having been silently rowed across the Charles under the guns of a British man-of-war, he mounted one of the fastest horses in the colony, to warn first Lexington (where Samuel Adams and John Hancock were distancing themselves from Boston and possible arrest) and then Concord that the British were coming. In Lexington, Revere, joined by another Committee of Correspondence dispatch rider, was briefly stopped by a British patrol. After supplying "information" (with a gun to his head), the printer-silversmith-revolutionary and his partner managed to break away by galloping off in opposite directions. Armed with Revere's "information," the British patrol rode back to say that at least five hundred Minutemen were waiting on Lexington Green. The several hundred British soldiers who approached the green early the next morning were probably surprised to find a motley army of seventy-seven, including boys, old men, and a slave.21

Ordering British troops not to fire, Pitcairn told the Americans to drop their weapons and disperse. Lexington's militia, led by Captain John Parker, a farmer and a veteran of the French and Indian Wars, was not eager for battle, either. But just as Parker gave the order to withdraw, a musket (American or British) flashed in the pan. There were now scattered shots from both sides. Eight Americans died and nine were wounded before the firing stopped. "O what a glorious morning is this!" said Samuel Adams, hearing the guns from his refuge near Lexington.

Prince Estabrook, a Lexington slave and member of Captain Parker's company, was one of the Americans who fought on Lexington Green that first morning of the Revolution. Later in the day other black militiamen from neighboring towns met the British at Concord, Arlington, Lincoln, and points on the road back to Boston.

According to the historian Howard Peckham, the Battle of Lexington lasted about fifteen minutes and the Battle of Concord lasted about five.22 Entering Concord without resistance at around eight a.m., Smith's men found some four hundred Minutemen waiting at North Bridge, including the Reverend William Emerson, whose grandson Ralph Waldo Emerson would write of the "rude bridge" and the "shot heard round the world." In Concord, the British fired first. Three British and two Americans were killed before the Americans retreated. Prince Estabrook, veteran of Lexington, was wounded. He was listed on the official roster of "Provincials" killed or wounded at Concord as "a Negro man"-the only victim not called "Mr."23 The American casualties were 41 wounded and 49 dead. The British counted 73 dead, 174 wounded, and 26 missing.24

There were other black militiamen defending North Bridge: Peter Salem of Framingham, who had been freed to enlist; Samuel Craft, of Newton; Caesar Ferrit and his son John, of Natick; Pompy, of Braintree; Pomp Blackman; and Prince, of Brookline (the slave of Joshua Boylston).25 The twenty-two-year-old Lemuel Haynes had marched all the way to Concord with his Connecticut militia regiment.

Haynes had just missed Lexington: his company was en route from Granville, Connecticut, when the battle broke out. But he made it to Concord, and shortly after the battle the "former indentured servant and patriot versus bruit Tyranny" wrote a poem, "The inhuman tragedy perpetrated 19th of April 1775 by a number of the British Troops under the command of Thomas Gage," signed "Lemuel a Young Mollato": "For Liberty, each Freeman Strives / As its a gift of God / And for it willing yield their Lives . . . Much better there, in Death Confin'd / than a Surviving Slave."26

Recenzii

“A triumphant American success story.”

—Stephen E. Ambrose

“A remarkable human drama, one of struggle, betrayal and ultimate redemption . . . Buckley has written a book to fill a significant gap in our history.”

—The New York Times

“A mine of powerful anecdotes, characters and forgotten history. You can open American Patriots practically anywhere and find yourself fascinated.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“With their blood and courage, they lift us all up. . . . A fascinating, stirring and important book.” —Mark Bowden, author of Black Hawk Down

“A compulsive and humbling history of nobility in the face of American prejudice, and courage in the face of America’s enemies. Buckley writes with grace and authority—and an almost unearthly restraint.” —John le Carré

—Stephen E. Ambrose

“A remarkable human drama, one of struggle, betrayal and ultimate redemption . . . Buckley has written a book to fill a significant gap in our history.”

—The New York Times

“A mine of powerful anecdotes, characters and forgotten history. You can open American Patriots practically anywhere and find yourself fascinated.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“With their blood and courage, they lift us all up. . . . A fascinating, stirring and important book.” —Mark Bowden, author of Black Hawk Down

“A compulsive and humbling history of nobility in the face of American prejudice, and courage in the face of America’s enemies. Buckley writes with grace and authority—and an almost unearthly restraint.” —John le Carré

Descriere

In a bestselling exploration of black American military heroes from Crispus Attucks to Colin Powell, Buckley presents a history of bravery, valor, patriotism, and extraordinary personal courage both on and off the battlefield.

Premii

- Black Caucus of the American Library Association Literary_award Honor Book, 2002

- Robert F. Kennedy Book Award Winner, 2002