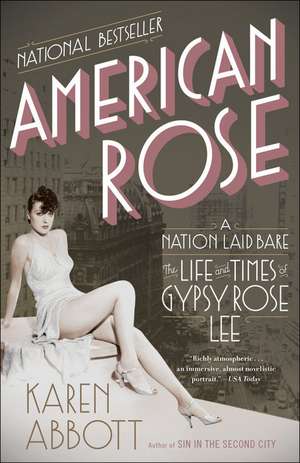

American Rose: The Life and Times of Gypsy Rose Lee

Autor Karen Abbotten Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 feb 2012

America was flying high in the Roaring Twenties. Then, almost overnight, the Great Depression brought it crashing down. When the dust settled, people were primed for a star who could distract them from reality. Enter Gypsy Rose Lee, a strutting, bawdy, erudite stripper who possessed a gift for delivering exactly what America needed. With her superb narrative skills and eye for detail, Karen Abbott brings to life an era of ambition, glamour, struggle, and survival. Using exclusive interviews and never-before-published material, she vividly delves into Gypsy’s world, including her intense triangle relationship with her sister, actress June Havoc, and their formidable mother, Rose, a petite but ferocious woman who literally killed to get her daughters on the stage. Weaving in the compelling saga of the Minskys—four scrappy brothers from New York City who would pave the way for Gypsy Rose Lee’s brand of burlesque and transform the entertainment landscape—Karen Abbott creates a rich account of a legend whose sensational tale of tragedy and triumph embodies the American Dream.

Preț: 128.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.66€ • 25.74$ • 20.41£

24.66€ • 25.74$ • 20.41£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812978513

ISBN-10: 081297851X

Pagini: 422

Ilustrații: B/W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 081297851X

Pagini: 422

Ilustrații: B/W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City. A native of Philadelphia, she now lives in New York City with her husband and two African Grey parrots who do a mean Ethel Merman. Visit her online at www.karenabbott.net.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Everybody thinks it's all so easy. Sure. Mother says I'm the most beautiful naked ass-well, I'm not. I'm the smartest. -Gypsy Rose Lee

New York World's Fair, 1940

In late spring, across a stretch of former wasteland in Flushing Meadows, Queens, a quarter-million people pay 50 cents each to forget and to dream. In the last decade they lost jobs and homes and now they face bleaker losses in the years to come: fathers and sons and husbands, a fragile faith that the worst has passed, the hope that America will never again be called to save the world. They come by boat and train and trolley and bus, hitchhike across four states in as many days, engagement rings tucked deep inside pockets along with every dollar they own. Not one inch of the fair's1,216 acres betrays its inglorious past as a dump, Gatsby's valley of ashes come to life, where towering heaps of debris meandered in an ironic skyline. Instead, beyond the gates, a "World of Tomorrow" beckons, offering flamboyant distractions and bewitching sleight of hand, a glimpse of fantasy without the promise that it will ever come to pass.

They have never seen anything like the Trylon, its gaunt steel ribs stretching seven hundred feet high, carrying bodies skyward on the largest escalator in the world. They chase salty scoops of Romanian caviar with swigs of aged Italian Barolo. On one soft spring day they admire Joe DiMaggio as he accepts the Golden Laurel of Sport Award. At the Aquacade exhibition they watch comely "aqua belles" perform intricate, synchronized routines, the water kept extra cold so as to stimulate goose flesh and nipples. They hear Mayor Fiorello La Guardia boom with optimistic predictions: "We will be dedicating a fair to the hope of the people of the world. The contrast must be striking to everyone. While other countries are in the twilight of an unhappy age, we are approaching the dawn of a new day." The Westinghouse Time Capsule, to remain sealed until a.d. 6939, contains fragments of their lives: microfilm of Gone with the Wind, a kewpie doll, samples of asbestos, a dollar in change. At night, when fireworks begin, they fall silent watching the colors crisscross overhead, hot tails branding the sky, imprinting a patchwork of lovely scars.

They wait in lines for hours to glimpse a reality that seems both distant and distinctly possible. Revolving chairs equipped with individual loudspeakers transport them through General Motors' Futurama exhibit, a vast model of America in 1960, where radio-controlled cars never veer off course on fourteen-lane highways and "undesirable slum areas" are wiped out. They witness a robot named Elektro issue commands to his mechanical dog, Sparko. They marvel at an array of new inventions: the fax machine, nylon stockings, a 12-foot-long electric shaver. One thousand of themwatch the fair's opening ceremonies on NBC's experimental station, W2XBS."Sooner than you realize it," advertisements for the telecast predict, "television will play a vital part in the life of the average American."

But this World of Tomorrow can't obscure the dangers of the world of today, despite the fair committee's efforts. The new officials logan, "Peace and Freedom," is absurdly incongruous with the hourly war bulletins that blare over the public address system. Visitors who brave the foreign section find only a melancholy museum of things past. The Netherlands building is dark and vacant, the Danish exhibit downsized into smaller quarters. Poland, Norway, and Finland still have a presence, but fly their flags at half-mast and display grim galleries that show photographs of demolished historical buildings and list names of the distinguished dead. The Soviet Pavilion is razed and replaced by a space called the "American Common," complete with "I Am an American Day." Fairgoers line up at the Belgium Pavilion when that nation falls to Germany, as if waiting to pay their respects at a wake. They wish this slim wedge of time between troubles past and future could pause indefinitely, but understand that New York is capable of everything but standing still.

On May 20, thousands of them-a crowd larger than the turnout for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Wendell Willkie combined-find temporary solace at the Hall of Music, where they wait to see Gypsy Rose Lee in her World's Fair debut. A forty-foot-tall billboard flaunting her image looms above the entrance, those skyscraper legs and swerving hips a respite from the hard lines and stark angles of this futuristic fantasy. She wears an expression both impish and imperious, a baited half smile that summons them closer yet suggests they'll never arrive.

Inside her dressing room, Gypsy reclines on a chaise lounge and holds a glass of brandy in shaking hands. The smoky-sweet scent of knockwurst drifts over from her hot plate, but her appetite is gone. She can hear them, the dull thrum of their expectations, the drumbeat chants of her name. Gypsy Rose Lee, voted the most popular woman in America, outpolling even Eleanor Roosevelt. Gypsy Rose Lee, who boasts that her own billboard is "larger than Stalin's." Gypsy Rose Lee, the only woman in the world, according to Life magazine, "with a public body and a private mind, bothequally exciting." Gypsy Rose Lee, whose best talent-whose only talent-is becoming whatever America needs at any given time. Gypsy Rose Lee, who, at the moment, is as mysterious to herself as she is to the gathering strangers outside.

She sips her brandy, lights a Murad cigarette. The voices beyond these four tight walls grow louder still, but can't overtake her thoughts. At age twenty-nine, she stands, precisely and precariously, on her own personal midway, cluttered with roaring secrets from her past and muted fears for her future, an equal number of years ahead in her life as behind. A half-dozen scrapbooks are fat with clippings from vaudeville and burlesque, her first marriage and Hollywood career, her political activism and opening nights; a half-dozen more, blank and empty, wait for her to fill the pages. Not a day passes without her retelling, if just to her own ears, the densely woven and tightly knotted story of her own legend, and not a day passes when she doesn't wonder how its final line will read.

She senses that the next chapter might begin with Michael Todd, the man who said he'd give his right ball to hire her, who granted her the Stalin-sized billboard and a second chance with New York. Earlier that afternoon, he banged on her dressing room door, and she took her time letting him in.

"What's the matter in there?" he asked, pushing his way inside. "Can't you read?" He pointed his cigar toward a sign on the notice board: no cooking backstage.

"Of course I can read. It saves money," Gypsy said in that inimitable voice. She's worked for years on that voice, scrubbing the Seattle out of it, ironing it smooth, tolling her words like bells: "rare" became rar-er-a. It is both charming and affected and, she neither raised a decibel or compressed to a whisper, positively terrifying. It makes babies cry and one of her dogs urinate in fear.

"On your salary," Mike responded, "I can't afford to have you stinking up the theater."

Gypsy invited him to try her knockwurst, and he sat down across from her. She smiled at his singular philosophy about money and success: "I've been broke but I've never been poor," he told her. "Being poor is a state of mind. Being broke is only a temporary situation." She noted his graceful, fluid movements, strangely at odds with his features: rectangular, filet-thick hands dead-ending into tubular fingers, a head that sat atop a brick of a neck. He nearly licked the plate, and afterward ripped down the sign.

A cheapskate, Gypsy thinks, but not a hypocrite. Just like her, on both counts. She suspects they'll work well together now and in the future, since they both understand that ambition comes first and money matters most.

She sets her brandy down on her vanity, making room amid a Roget's Thesaurus, millipede-sized pairs of false eyelashes, an ashtray, a type writer. Whenever she's not performing she plans to work on her novel, a murder mystery set in an old burlesque theater; the book counts as one bold step into her blank and waiting future. She's told favored members of the press about her literary ambitions, confessing that she's lousy at punctuation due to her limited schooling and sharing her theories about storytelling. "I don't like poison darts emerging from the middle of the Belgian Congo," she says, "and I think there is no sense having people killed before the reader is acquainted with them."

She doesn't mention that she has a few authentic, true-life murders in her past, or that the person responsible has recently resurfaced, sending a terse, cryptic note that concludes: "I hope you are well and very happy."

Which, coming from Mother, signals another gauntlet thrown.

The four syllables of her name thrash inside her ears. It's time, now, and she makes her body comply. One last review in the full-length mirror, a slow turn that captures every angle and inch. She knows the crowd outside doesn't care who she plans to be. They want the Gypsy Rose Lee they already know, the one whose act has remained unchanged for nearly ten years; they delight in the absence of surprise. They'll look for her trademark outfit: the Victorian hoop skirt, the Gibson Girl coif, the plume hat slouching over one winking eye, the size 10? brocade heels, the bow that makes an exotic gift of her long, pale neck. They'll wait for the slow roll of stocking over knee, strain to glimpse a patch of shoulder. They'll beg for more and will be secretly pleased when she refuses. She knows that what she hides is as much of a reward as what she deigns to reveal.

The curtain yields and admits her to the other side. She senses the spotlight darting and chasing, feels it pin her into place. Voices circle one last time and collapse into silence, waiting.

"Have you the faintest idea of the private life of a stripteaser?" she begins, caught between her personal, unwritten World of Tomorrow, and deeper and deeper yesterdays.

Chapter Two

Do unto others before they do you. -Rose Thompson Hovick

Seattle, Washington, 1910s

No matter what Rose Hovick tried-hurling herself down flights of stairs, jabbing herself in the stomach, refusing food for days, sitting in scalding water-the baby, her second, would not go still inside her. A preternaturally stubborn little thing, which she should have taken as a sign. She wanted a boy, even though men did not last long in her house. Her first child, Ellen June, was a chubby brunette, twelve pounds at birth, tearing her mother on her way out. The house had no running water, and the attending midwife washed the baby clean with snow. A caul had covered her face, which meant she had a gift for seeing the future as clearly as the past. But she was clumsy, too, and by age three already diluting Rose's dreams.

Ellen June's new sibling arrived early and when it was most inconvenient for Rose, during a trip to Vancouver, but the baby was instantly forgiven-even for being a girl. This second daughter had a sprig of bright yellow hair and blue eyes with dark circles etched beneath them, as if she were already weary, and her head seemed tiny enough to fit into a teacup. She could spin perfect circles on her toes before she could talk, and Rose decided that since the girl had refused to be destroyed, she might consent to being created. Rose would give the baby everything-even things not rightfully hers to give-including her older daughter's name, the first and favorite name. From then on the original Ellen June was called Rose Louise, Louise for short-a consolation prize of a name, half borrowed from her mother. It was the first of many times she would become someone else. In the beginning the family lived in a bungalow on West Frontenac Street in Seattle, built of crooked wooden slats and a sloping shingled roof, squat as a bulldog, four rooms that felt like one, the kind of dank, dreary home that looked inviting only in a rainstorm. A porch jutted from the front, supported by columns where Rose could string wet laundry, had she been that kind of housewife. The place had a single grace note: the tiny square of Puget Sound visible from one window.

No matter where Louise or Ellen June (nicknamed "June") hid, their mother's voice could find them. "Her low tones were musical," June said, but "her fury was like the booming of a cannon." Rose had married John "Jack" Hovick in 1910 at age eighteen, one month pregnant with Louise, and by 1913, when her dainty baby June was born, she had already left and returned to her husband half a dozen times. She vowed to memorize his offenses, real or imagined, so that when the day came she could recite her lines in just one take.

Rose got her chance in the summer of 1914, when she placed her hand on a Bible in a King County courtroom, a box of tissues by her side. Your Honor, she began, her husband, Jack Hovick, forced her and their daughters to live in an apartment on Seattle's Rainier Beach that was "damp and full of knot holes"-unacceptable, especially for a woman suffering from the grippe and weak lungs. Their next apartment was no better, what with its "bad reputation" and tenants of questionable character. She and her husband separated, reconciled, separated again. Rose so feared for her and her daughters' safety that she had applied for a restraining order against Jack, and nailed shut the door and every window. He had threatened to steal Louise and June, never to bring them back. "If I could only get the kids," he'd said, "it is all I would want."

She wept for a moment at the horror of the memory. The courtroom quieted, waiting for her to compose herself.

Once, Rose continued, Jack broke through the glass, trashed all the furniture, and stole the bedrails, leaving her to sleep on the floor. He also "struck and choked" his wife and once beat Louise "almost insensible, slapped and kicked her and put her in a dark closet on account of some trivial matter."

Her husband made $100 a month as an advertising agent for The Seattle Sun yet refused, during all of their married life, to buy Rose even one hat or a dress suit or "any underwear to speak of." He never gave her money to spend on herself or for "any purpose whatever"-including private dance lessons for Louise and June, although she omitted this last grievance from her public testimony. Rose would use the girls not to escape a life she'd never wanted, but instead to access one that had always stood just out of her reach.

From the Hardcover edition.

Everybody thinks it's all so easy. Sure. Mother says I'm the most beautiful naked ass-well, I'm not. I'm the smartest. -Gypsy Rose Lee

New York World's Fair, 1940

In late spring, across a stretch of former wasteland in Flushing Meadows, Queens, a quarter-million people pay 50 cents each to forget and to dream. In the last decade they lost jobs and homes and now they face bleaker losses in the years to come: fathers and sons and husbands, a fragile faith that the worst has passed, the hope that America will never again be called to save the world. They come by boat and train and trolley and bus, hitchhike across four states in as many days, engagement rings tucked deep inside pockets along with every dollar they own. Not one inch of the fair's1,216 acres betrays its inglorious past as a dump, Gatsby's valley of ashes come to life, where towering heaps of debris meandered in an ironic skyline. Instead, beyond the gates, a "World of Tomorrow" beckons, offering flamboyant distractions and bewitching sleight of hand, a glimpse of fantasy without the promise that it will ever come to pass.

They have never seen anything like the Trylon, its gaunt steel ribs stretching seven hundred feet high, carrying bodies skyward on the largest escalator in the world. They chase salty scoops of Romanian caviar with swigs of aged Italian Barolo. On one soft spring day they admire Joe DiMaggio as he accepts the Golden Laurel of Sport Award. At the Aquacade exhibition they watch comely "aqua belles" perform intricate, synchronized routines, the water kept extra cold so as to stimulate goose flesh and nipples. They hear Mayor Fiorello La Guardia boom with optimistic predictions: "We will be dedicating a fair to the hope of the people of the world. The contrast must be striking to everyone. While other countries are in the twilight of an unhappy age, we are approaching the dawn of a new day." The Westinghouse Time Capsule, to remain sealed until a.d. 6939, contains fragments of their lives: microfilm of Gone with the Wind, a kewpie doll, samples of asbestos, a dollar in change. At night, when fireworks begin, they fall silent watching the colors crisscross overhead, hot tails branding the sky, imprinting a patchwork of lovely scars.

They wait in lines for hours to glimpse a reality that seems both distant and distinctly possible. Revolving chairs equipped with individual loudspeakers transport them through General Motors' Futurama exhibit, a vast model of America in 1960, where radio-controlled cars never veer off course on fourteen-lane highways and "undesirable slum areas" are wiped out. They witness a robot named Elektro issue commands to his mechanical dog, Sparko. They marvel at an array of new inventions: the fax machine, nylon stockings, a 12-foot-long electric shaver. One thousand of themwatch the fair's opening ceremonies on NBC's experimental station, W2XBS."Sooner than you realize it," advertisements for the telecast predict, "television will play a vital part in the life of the average American."

But this World of Tomorrow can't obscure the dangers of the world of today, despite the fair committee's efforts. The new officials logan, "Peace and Freedom," is absurdly incongruous with the hourly war bulletins that blare over the public address system. Visitors who brave the foreign section find only a melancholy museum of things past. The Netherlands building is dark and vacant, the Danish exhibit downsized into smaller quarters. Poland, Norway, and Finland still have a presence, but fly their flags at half-mast and display grim galleries that show photographs of demolished historical buildings and list names of the distinguished dead. The Soviet Pavilion is razed and replaced by a space called the "American Common," complete with "I Am an American Day." Fairgoers line up at the Belgium Pavilion when that nation falls to Germany, as if waiting to pay their respects at a wake. They wish this slim wedge of time between troubles past and future could pause indefinitely, but understand that New York is capable of everything but standing still.

On May 20, thousands of them-a crowd larger than the turnout for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Wendell Willkie combined-find temporary solace at the Hall of Music, where they wait to see Gypsy Rose Lee in her World's Fair debut. A forty-foot-tall billboard flaunting her image looms above the entrance, those skyscraper legs and swerving hips a respite from the hard lines and stark angles of this futuristic fantasy. She wears an expression both impish and imperious, a baited half smile that summons them closer yet suggests they'll never arrive.

Inside her dressing room, Gypsy reclines on a chaise lounge and holds a glass of brandy in shaking hands. The smoky-sweet scent of knockwurst drifts over from her hot plate, but her appetite is gone. She can hear them, the dull thrum of their expectations, the drumbeat chants of her name. Gypsy Rose Lee, voted the most popular woman in America, outpolling even Eleanor Roosevelt. Gypsy Rose Lee, who boasts that her own billboard is "larger than Stalin's." Gypsy Rose Lee, the only woman in the world, according to Life magazine, "with a public body and a private mind, bothequally exciting." Gypsy Rose Lee, whose best talent-whose only talent-is becoming whatever America needs at any given time. Gypsy Rose Lee, who, at the moment, is as mysterious to herself as she is to the gathering strangers outside.

She sips her brandy, lights a Murad cigarette. The voices beyond these four tight walls grow louder still, but can't overtake her thoughts. At age twenty-nine, she stands, precisely and precariously, on her own personal midway, cluttered with roaring secrets from her past and muted fears for her future, an equal number of years ahead in her life as behind. A half-dozen scrapbooks are fat with clippings from vaudeville and burlesque, her first marriage and Hollywood career, her political activism and opening nights; a half-dozen more, blank and empty, wait for her to fill the pages. Not a day passes without her retelling, if just to her own ears, the densely woven and tightly knotted story of her own legend, and not a day passes when she doesn't wonder how its final line will read.

She senses that the next chapter might begin with Michael Todd, the man who said he'd give his right ball to hire her, who granted her the Stalin-sized billboard and a second chance with New York. Earlier that afternoon, he banged on her dressing room door, and she took her time letting him in.

"What's the matter in there?" he asked, pushing his way inside. "Can't you read?" He pointed his cigar toward a sign on the notice board: no cooking backstage.

"Of course I can read. It saves money," Gypsy said in that inimitable voice. She's worked for years on that voice, scrubbing the Seattle out of it, ironing it smooth, tolling her words like bells: "rare" became rar-er-a. It is both charming and affected and, she neither raised a decibel or compressed to a whisper, positively terrifying. It makes babies cry and one of her dogs urinate in fear.

"On your salary," Mike responded, "I can't afford to have you stinking up the theater."

Gypsy invited him to try her knockwurst, and he sat down across from her. She smiled at his singular philosophy about money and success: "I've been broke but I've never been poor," he told her. "Being poor is a state of mind. Being broke is only a temporary situation." She noted his graceful, fluid movements, strangely at odds with his features: rectangular, filet-thick hands dead-ending into tubular fingers, a head that sat atop a brick of a neck. He nearly licked the plate, and afterward ripped down the sign.

A cheapskate, Gypsy thinks, but not a hypocrite. Just like her, on both counts. She suspects they'll work well together now and in the future, since they both understand that ambition comes first and money matters most.

She sets her brandy down on her vanity, making room amid a Roget's Thesaurus, millipede-sized pairs of false eyelashes, an ashtray, a type writer. Whenever she's not performing she plans to work on her novel, a murder mystery set in an old burlesque theater; the book counts as one bold step into her blank and waiting future. She's told favored members of the press about her literary ambitions, confessing that she's lousy at punctuation due to her limited schooling and sharing her theories about storytelling. "I don't like poison darts emerging from the middle of the Belgian Congo," she says, "and I think there is no sense having people killed before the reader is acquainted with them."

She doesn't mention that she has a few authentic, true-life murders in her past, or that the person responsible has recently resurfaced, sending a terse, cryptic note that concludes: "I hope you are well and very happy."

Which, coming from Mother, signals another gauntlet thrown.

The four syllables of her name thrash inside her ears. It's time, now, and she makes her body comply. One last review in the full-length mirror, a slow turn that captures every angle and inch. She knows the crowd outside doesn't care who she plans to be. They want the Gypsy Rose Lee they already know, the one whose act has remained unchanged for nearly ten years; they delight in the absence of surprise. They'll look for her trademark outfit: the Victorian hoop skirt, the Gibson Girl coif, the plume hat slouching over one winking eye, the size 10? brocade heels, the bow that makes an exotic gift of her long, pale neck. They'll wait for the slow roll of stocking over knee, strain to glimpse a patch of shoulder. They'll beg for more and will be secretly pleased when she refuses. She knows that what she hides is as much of a reward as what she deigns to reveal.

The curtain yields and admits her to the other side. She senses the spotlight darting and chasing, feels it pin her into place. Voices circle one last time and collapse into silence, waiting.

"Have you the faintest idea of the private life of a stripteaser?" she begins, caught between her personal, unwritten World of Tomorrow, and deeper and deeper yesterdays.

Chapter Two

Do unto others before they do you. -Rose Thompson Hovick

Seattle, Washington, 1910s

No matter what Rose Hovick tried-hurling herself down flights of stairs, jabbing herself in the stomach, refusing food for days, sitting in scalding water-the baby, her second, would not go still inside her. A preternaturally stubborn little thing, which she should have taken as a sign. She wanted a boy, even though men did not last long in her house. Her first child, Ellen June, was a chubby brunette, twelve pounds at birth, tearing her mother on her way out. The house had no running water, and the attending midwife washed the baby clean with snow. A caul had covered her face, which meant she had a gift for seeing the future as clearly as the past. But she was clumsy, too, and by age three already diluting Rose's dreams.

Ellen June's new sibling arrived early and when it was most inconvenient for Rose, during a trip to Vancouver, but the baby was instantly forgiven-even for being a girl. This second daughter had a sprig of bright yellow hair and blue eyes with dark circles etched beneath them, as if she were already weary, and her head seemed tiny enough to fit into a teacup. She could spin perfect circles on her toes before she could talk, and Rose decided that since the girl had refused to be destroyed, she might consent to being created. Rose would give the baby everything-even things not rightfully hers to give-including her older daughter's name, the first and favorite name. From then on the original Ellen June was called Rose Louise, Louise for short-a consolation prize of a name, half borrowed from her mother. It was the first of many times she would become someone else. In the beginning the family lived in a bungalow on West Frontenac Street in Seattle, built of crooked wooden slats and a sloping shingled roof, squat as a bulldog, four rooms that felt like one, the kind of dank, dreary home that looked inviting only in a rainstorm. A porch jutted from the front, supported by columns where Rose could string wet laundry, had she been that kind of housewife. The place had a single grace note: the tiny square of Puget Sound visible from one window.

No matter where Louise or Ellen June (nicknamed "June") hid, their mother's voice could find them. "Her low tones were musical," June said, but "her fury was like the booming of a cannon." Rose had married John "Jack" Hovick in 1910 at age eighteen, one month pregnant with Louise, and by 1913, when her dainty baby June was born, she had already left and returned to her husband half a dozen times. She vowed to memorize his offenses, real or imagined, so that when the day came she could recite her lines in just one take.

Rose got her chance in the summer of 1914, when she placed her hand on a Bible in a King County courtroom, a box of tissues by her side. Your Honor, she began, her husband, Jack Hovick, forced her and their daughters to live in an apartment on Seattle's Rainier Beach that was "damp and full of knot holes"-unacceptable, especially for a woman suffering from the grippe and weak lungs. Their next apartment was no better, what with its "bad reputation" and tenants of questionable character. She and her husband separated, reconciled, separated again. Rose so feared for her and her daughters' safety that she had applied for a restraining order against Jack, and nailed shut the door and every window. He had threatened to steal Louise and June, never to bring them back. "If I could only get the kids," he'd said, "it is all I would want."

She wept for a moment at the horror of the memory. The courtroom quieted, waiting for her to compose herself.

Once, Rose continued, Jack broke through the glass, trashed all the furniture, and stole the bedrails, leaving her to sleep on the floor. He also "struck and choked" his wife and once beat Louise "almost insensible, slapped and kicked her and put her in a dark closet on account of some trivial matter."

Her husband made $100 a month as an advertising agent for The Seattle Sun yet refused, during all of their married life, to buy Rose even one hat or a dress suit or "any underwear to speak of." He never gave her money to spend on herself or for "any purpose whatever"-including private dance lessons for Louise and June, although she omitted this last grievance from her public testimony. Rose would use the girls not to escape a life she'd never wanted, but instead to access one that had always stood just out of her reach.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Richly atmospheric . . . an immersive, almost novelistic portrait.”—USA Today

“American Rose is a fitting tribute to an amazing woman, telling her story beautifully while revealing as much about post-Depression America as it does about celebrity life. It’s cultural history at its best.”—Rebecca Skloot, New York Times bestselling author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

“Abbott creates a brainy striptease similar to the one her subject may have performed.”—Newsday

“With staggeringly in-depth research . . . Abbott composes a story wrought with personal drama and insight into a dark era in American history. . . . The story is as beguiling as it is timeless.”—Elle

“At its core, American Rose is a haunting portrait of a woman . . . offering her audiences a sassy, confident self while making sure they would never know the damaged soul who created her.”—Los Angeles Times

“Sad, smart, brassy . . . the true story of the Queen of Burlesque is even weirder and wilder than the legend.”—Salon

“American Rose is a fitting tribute to an amazing woman, telling her story beautifully while revealing as much about post-Depression America as it does about celebrity life. It’s cultural history at its best.”—Rebecca Skloot, New York Times bestselling author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

“Abbott creates a brainy striptease similar to the one her subject may have performed.”—Newsday

“With staggeringly in-depth research . . . Abbott composes a story wrought with personal drama and insight into a dark era in American history. . . . The story is as beguiling as it is timeless.”—Elle

“At its core, American Rose is a haunting portrait of a woman . . . offering her audiences a sassy, confident self while making sure they would never know the damaged soul who created her.”—Los Angeles Times

“Sad, smart, brassy . . . the true story of the Queen of Burlesque is even weirder and wilder than the legend.”—Salon

Descriere

In this national bestseller, the author of the acclaimed "Sin in the Second City" chronicles the gripping and expansive story of America's coming-of-age--told through the extraordinary life of Gypsy Rose Lee and the world she survived and conquered.