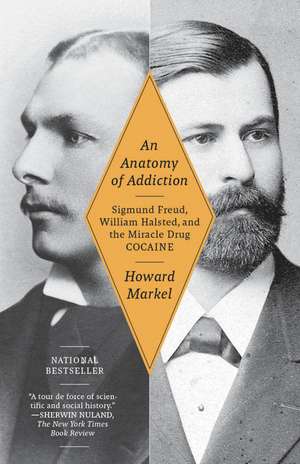

An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine

Autor Howard Markelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2012

When Freud and Halsted began their experiments with cocaine in the 1880s, neither they, nor their colleagues, had any idea of the drug's potential to dominate and endanger their lives. An Anatomy of Addiction tells the tragic and heroic story of each man, accidentally struck down in his prime by an insidious malady: tragic because of the time, relationships, and health cocaine forced each to squander; heroic in the intense battle each man waged to overcome his affliction. Markel writes of the physical and emotional damage caused by the then-heralded wonder drug, and how each man ultimately changed the world in spite of it--or because of it. One became the father of psychoanalysis; the other, of modern surgery. Here is the full story, long overlooked, told in its rich historical context.

Preț: 94.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.15€ • 19.78$ • 15.30£

18.15€ • 19.78$ • 15.30£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400078790

ISBN-10: 1400078792

Pagini: 314

Ilustrații: 111 B& W ILLUS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400078792

Pagini: 314

Ilustrații: 111 B& W ILLUS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Howard Markel, M.D., Ph.D., is the George E. Wantz Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. His books include Quarantine! and When Germs Travel. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and The New England Journal of Medicine, and he is a frequent contributor to National Public Radio. Markel is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences and lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Extras

Prologue

On the morning of May 5, 1885, in lower Manhattan, a worker fell from a building’s scaffolding to the ground. A splintered bone protruded from his bloody trousers; a plaintive wail signaled his pain; and soon he was taken from the scene by horse-drawn ambulance to Bellevue Hospital. At the hospital, in the dispensary, a young surgeon named William Stewart Halsted frantically searched the shelves for a container of cocaine.

In the late nineteenth century, there were no such things as “controlled substances,” let alone illegal drugs. Bottles of morphine, cocaine, and other powerful, habit-forming pills and tonics were easily found in virtually every hospital, clinic, drugstore, and doctor’s black bag. Consequently, it took less than a few minutes for the surgeon to find a vial of cocaine. He drew a precise dose into a hypodermic syringe, rolled up his sleeve, and searched for a fresh spot on his scarred forearm. Upon doing so, he inserted the needle and pushed down on the syringe’s plunger. Almost immediately, he felt a wave of relief and an overwhelming sense of euphoria. His pulse bounded and his mind raced, but his body, paradoxically, relaxed.

The orderlies rushed the laborer into Bellevue’s accident room (the forerunner of today’s emergency departments) for examination and treatment. A compound fracture—the breaking of a bone so severely that it pokes through the soft tissue and skin—was deadly serious in the late nineteenth century. Before X-ray technology, it was difficult to assess the full extent of a fracture other than by means of painful palpation or cutting open the body part in question for a closer look. Discounting the attendant risks of infection and subsequent amputation, even in the best of surgical hands these injuries often carried a “hopeless prognosis.” At Bellevue, above the table on which these battered patients were placed, a sign painted on the wall suggested the chances of recuperation. It read, in six-inch-high black letters: PREPARE TO MEET YOUR GOD.

As the worker writhed in agony, one surgeon’s name crossed the lips of every staff member working in the accident room: Halsted. When it came to a crisis of the body, few surgeons were faster or more expert than he. Leg fractures were a particular interest of his in an era when buildings were being thrown up daily and construction workers were falling off them almost as frequently. One of Dr. Halsted’s earliest scientific papers assessed the surgical repair of fractured thigh, or femur, bones using a series of geometric equations based on how the leg adducted (drew toward) and abducted (drew away) from the central axis of the body. Such meticulous analysis was essential to repairing the break in a manner that accounted for the potential of the injured limb to shorten after the injury. Otherwise, the broken leg would heal in a manner that resulted in a decided limp or, given the intricate mechanics of the hip joint, much worse.

An orderly was dispatched to find Dr. Halsted as soon as possible. Running through the labyrinthine corridors of the hospital, he shouted, “Paging Dr. Halsted! Fresh fracture in the Accident Room! Paging Dr. Halsted!” Down one of these halls, in a rarely used chamber, the surgeon was entering a world of mindless bliss. He heard his name but didn’t really care to answer. Yet something, perhaps a reflex ingrained by his many years of surgical training, roused him to stagger out into the hallway and make his way downstairs. The pupils of his eyes looked like gaping black holes, his speech was rapid-fire, and his whole body seemed to vibrate as if he were electrified.

Upon entering the accident room, Halsted was confronted with the acrid smell of blood and a maelstrom of doctors and nurses attending to the wounded worker. So intense was the pain that when Halsted gruffly demanded the patient move his leg one way or the other, the man screamed out an emphatic “No!” Passing a hand up and down the length of the laborer’s lower leg, Halsted could feel the sharp ends of a shattered shinbone, or tibia, thrusting its way through the skin. It was a gory mess requiring immediate attention.

An effective surgeon must be able to visualize the three-dimensional aspects of the anatomy he is about to manipulate. He must take great care in handling sensitive structures surrounding the area in question, such as nerves and blood vessels, to prevent cutting through or destroying them entirely, lest the procedure cause more problems than it corrects. Consequently, the surgeon needs to think several steps ahead of the maneuver he is actively performing in order to achieve the best results for his patient. But the cocainized Halsted was in no shape to operate.

Halsted stepped back from the examination table while the nurses and junior physicians awaited his command, mindful that in a moment bacteria could enter the wound and wreak havoc, perhaps leaving this laborer unable to walk again—or even to die from overwhelming sepsis. To their astonishment, the surgeon turned on his heels, walked out of the hospital, and hailed a cab to gallop him to his home on East Twenty-fifth Street. Once there, he sank into a cocaine oblivion that lasted more than seven months.

***

Forty-four hundred miles away, Sigmund Freud, an up-and-coming neurologist, toiled away in the busy wards of Vienna Krankenhaus (General Hospital). Like Halsted, he was fresh prey for cocaine’s grip. On May 17, 1885, twelve days after Halsted hurried out of Bellevue, Dr. Freud boasted to his fiancée how a dose of pure cocaine vanquished his migraine and inspired him to stay up until four in the morning writing a “very important” anatomical study that “should raise my esteem again in the eyes of the public.” In reality, the publication proved to be nothing more than an extraneous footnote to his literary oeuvre.

A year earlier, Freud had published an extensive review exploring cocaine’s potential therapeutic uses. His central experimental subject was himself. But as impressive as his work was, Dr. Freud neglected to describe cocaine’s most practical application: it was a superb anesthetic that completely numbed a living being’s sensation to the sharp blade of a scalpel. In the fall of 1884, a few months after Freud’s monograph appeared in print, a young ophthalmologist successfully demonstrated the drug’s power to kill pain. The discovery excited the entire medical world, much to Freud’s chagrin.

In the spring of 1885, the preempted Freud made plans to flee Vienna and nurse his wounded ego with a prestigious neuropathology fellowship in Paris. In the months that followed, he engaged in discussions of brain disorders, witnessed dozens of demonstrations of women and men suffering from hysteria, participated in detailed scientific research, and, too frequently, self-medicated his anxieties away.

Cocaine thrilled him in a manner that everyday life could not. He wrote romantic, often erotic letters to his fiancée, dreamed grandiose dreams of his future career, walked about the streets of Paris, visited museums and theaters, and attended sumptuous soirees—all under the influence. Even on return to his beloved Vienna in 1886, eager to embark upon his own private practice and excited about the possibility of new medical discoveries and explorations, Freud continued to take increasingly greater doses of cocaine.

***

The full-fledged diagnosis of addiction did not really exist in the medical literature until the late nineteenth century. The earliest use of the word appears in the statutes of Roman law. In antiquity, “addiction” typically referred to the bond of slavery that lenders imposed upon delinquent debtors or victims on their convicted aggressors. Such individuals were mandated to be “addicted” to the service of the person to whom they owed restitution. By the seventeenth century and extending well into the early 1800s, “addiction” described people compelled to act out any number of bad habits. Those abusing narcotics during this period were called opium and morphine “eaters.” Alcohol abusers, too, had their own pejorative descriptors, such as “the drunkard,” but as their problem came to the attention of physicians, the condition was often indexed in medical textbooks as dipsomania or alcoholism.

All this changed in the late nineteenth century with the overprescription of narcotics by doctors to ailing and unsuspecting patients. One of the most striking measures of this era was the alarming number of male doctors who prescribed opium, morphine, and laudanum (a tincture of macerated raw opium in 50 percent alcohol) to ever greater numbers of women patients. Any female complaining to her physician about so-called women’s problems was all but certain to leave the doctor’s office clutching a prescription. For example, epidemiological studies conducted in Michigan, Iowa, and Chicago between 1878 and 1885 reported that at least 60 percent of the morphine or opium addicts living there were women. Huge numbers of men and children, too, complaining of ailments ranging from acute pain to colic, heart disease, earaches, cholera, whooping cough, hemorrhoids, hysteria, and mumps were prescribed morphine and opium. A survey of Boston’s drugstores published in an 1888 issue of Popular Science Monthly documents the ubiquity of these narcotics: of 10,200 prescriptions reviewed, 1,481,or 14.5 percent, contained an opiate. During this period in the United States and abroad, the abuse of addictive drugs such as opium, morphine, and, soon after it was introduced to the public, cocaine constituted a major public health problem.

***

No evidence has been found to demonstrate that William Halsted and Sigmund Freud ever met. Separated by physical and cultural oceans, their lives were, nevertheless, intricately braided and shaped by a handful of scientific papers on the medicinal uses of cocaine. For Sigmund Freud, the medical profession’s creation of so many morphine addicts led him to experiment with cocaine as a potential antidote. In the quest to obliterate the pain incurred by the surgeon’s craft, William Halsted explored the drug as a safer form of anesthesia. But because cocaine was such a relatively new drug during this period, neither Freud nor Halsted recognized its addictive and deleterious force until it was much too late. By using themselves as guinea pigs in their research, each became dependent upon a substance that nearly destroyed their lives and the work that ultimately changed how we think, live, and heal.

From the Hardcover edition.

On the morning of May 5, 1885, in lower Manhattan, a worker fell from a building’s scaffolding to the ground. A splintered bone protruded from his bloody trousers; a plaintive wail signaled his pain; and soon he was taken from the scene by horse-drawn ambulance to Bellevue Hospital. At the hospital, in the dispensary, a young surgeon named William Stewart Halsted frantically searched the shelves for a container of cocaine.

In the late nineteenth century, there were no such things as “controlled substances,” let alone illegal drugs. Bottles of morphine, cocaine, and other powerful, habit-forming pills and tonics were easily found in virtually every hospital, clinic, drugstore, and doctor’s black bag. Consequently, it took less than a few minutes for the surgeon to find a vial of cocaine. He drew a precise dose into a hypodermic syringe, rolled up his sleeve, and searched for a fresh spot on his scarred forearm. Upon doing so, he inserted the needle and pushed down on the syringe’s plunger. Almost immediately, he felt a wave of relief and an overwhelming sense of euphoria. His pulse bounded and his mind raced, but his body, paradoxically, relaxed.

The orderlies rushed the laborer into Bellevue’s accident room (the forerunner of today’s emergency departments) for examination and treatment. A compound fracture—the breaking of a bone so severely that it pokes through the soft tissue and skin—was deadly serious in the late nineteenth century. Before X-ray technology, it was difficult to assess the full extent of a fracture other than by means of painful palpation or cutting open the body part in question for a closer look. Discounting the attendant risks of infection and subsequent amputation, even in the best of surgical hands these injuries often carried a “hopeless prognosis.” At Bellevue, above the table on which these battered patients were placed, a sign painted on the wall suggested the chances of recuperation. It read, in six-inch-high black letters: PREPARE TO MEET YOUR GOD.

As the worker writhed in agony, one surgeon’s name crossed the lips of every staff member working in the accident room: Halsted. When it came to a crisis of the body, few surgeons were faster or more expert than he. Leg fractures were a particular interest of his in an era when buildings were being thrown up daily and construction workers were falling off them almost as frequently. One of Dr. Halsted’s earliest scientific papers assessed the surgical repair of fractured thigh, or femur, bones using a series of geometric equations based on how the leg adducted (drew toward) and abducted (drew away) from the central axis of the body. Such meticulous analysis was essential to repairing the break in a manner that accounted for the potential of the injured limb to shorten after the injury. Otherwise, the broken leg would heal in a manner that resulted in a decided limp or, given the intricate mechanics of the hip joint, much worse.

An orderly was dispatched to find Dr. Halsted as soon as possible. Running through the labyrinthine corridors of the hospital, he shouted, “Paging Dr. Halsted! Fresh fracture in the Accident Room! Paging Dr. Halsted!” Down one of these halls, in a rarely used chamber, the surgeon was entering a world of mindless bliss. He heard his name but didn’t really care to answer. Yet something, perhaps a reflex ingrained by his many years of surgical training, roused him to stagger out into the hallway and make his way downstairs. The pupils of his eyes looked like gaping black holes, his speech was rapid-fire, and his whole body seemed to vibrate as if he were electrified.

Upon entering the accident room, Halsted was confronted with the acrid smell of blood and a maelstrom of doctors and nurses attending to the wounded worker. So intense was the pain that when Halsted gruffly demanded the patient move his leg one way or the other, the man screamed out an emphatic “No!” Passing a hand up and down the length of the laborer’s lower leg, Halsted could feel the sharp ends of a shattered shinbone, or tibia, thrusting its way through the skin. It was a gory mess requiring immediate attention.

An effective surgeon must be able to visualize the three-dimensional aspects of the anatomy he is about to manipulate. He must take great care in handling sensitive structures surrounding the area in question, such as nerves and blood vessels, to prevent cutting through or destroying them entirely, lest the procedure cause more problems than it corrects. Consequently, the surgeon needs to think several steps ahead of the maneuver he is actively performing in order to achieve the best results for his patient. But the cocainized Halsted was in no shape to operate.

Halsted stepped back from the examination table while the nurses and junior physicians awaited his command, mindful that in a moment bacteria could enter the wound and wreak havoc, perhaps leaving this laborer unable to walk again—or even to die from overwhelming sepsis. To their astonishment, the surgeon turned on his heels, walked out of the hospital, and hailed a cab to gallop him to his home on East Twenty-fifth Street. Once there, he sank into a cocaine oblivion that lasted more than seven months.

***

Forty-four hundred miles away, Sigmund Freud, an up-and-coming neurologist, toiled away in the busy wards of Vienna Krankenhaus (General Hospital). Like Halsted, he was fresh prey for cocaine’s grip. On May 17, 1885, twelve days after Halsted hurried out of Bellevue, Dr. Freud boasted to his fiancée how a dose of pure cocaine vanquished his migraine and inspired him to stay up until four in the morning writing a “very important” anatomical study that “should raise my esteem again in the eyes of the public.” In reality, the publication proved to be nothing more than an extraneous footnote to his literary oeuvre.

A year earlier, Freud had published an extensive review exploring cocaine’s potential therapeutic uses. His central experimental subject was himself. But as impressive as his work was, Dr. Freud neglected to describe cocaine’s most practical application: it was a superb anesthetic that completely numbed a living being’s sensation to the sharp blade of a scalpel. In the fall of 1884, a few months after Freud’s monograph appeared in print, a young ophthalmologist successfully demonstrated the drug’s power to kill pain. The discovery excited the entire medical world, much to Freud’s chagrin.

In the spring of 1885, the preempted Freud made plans to flee Vienna and nurse his wounded ego with a prestigious neuropathology fellowship in Paris. In the months that followed, he engaged in discussions of brain disorders, witnessed dozens of demonstrations of women and men suffering from hysteria, participated in detailed scientific research, and, too frequently, self-medicated his anxieties away.

Cocaine thrilled him in a manner that everyday life could not. He wrote romantic, often erotic letters to his fiancée, dreamed grandiose dreams of his future career, walked about the streets of Paris, visited museums and theaters, and attended sumptuous soirees—all under the influence. Even on return to his beloved Vienna in 1886, eager to embark upon his own private practice and excited about the possibility of new medical discoveries and explorations, Freud continued to take increasingly greater doses of cocaine.

***

The full-fledged diagnosis of addiction did not really exist in the medical literature until the late nineteenth century. The earliest use of the word appears in the statutes of Roman law. In antiquity, “addiction” typically referred to the bond of slavery that lenders imposed upon delinquent debtors or victims on their convicted aggressors. Such individuals were mandated to be “addicted” to the service of the person to whom they owed restitution. By the seventeenth century and extending well into the early 1800s, “addiction” described people compelled to act out any number of bad habits. Those abusing narcotics during this period were called opium and morphine “eaters.” Alcohol abusers, too, had their own pejorative descriptors, such as “the drunkard,” but as their problem came to the attention of physicians, the condition was often indexed in medical textbooks as dipsomania or alcoholism.

All this changed in the late nineteenth century with the overprescription of narcotics by doctors to ailing and unsuspecting patients. One of the most striking measures of this era was the alarming number of male doctors who prescribed opium, morphine, and laudanum (a tincture of macerated raw opium in 50 percent alcohol) to ever greater numbers of women patients. Any female complaining to her physician about so-called women’s problems was all but certain to leave the doctor’s office clutching a prescription. For example, epidemiological studies conducted in Michigan, Iowa, and Chicago between 1878 and 1885 reported that at least 60 percent of the morphine or opium addicts living there were women. Huge numbers of men and children, too, complaining of ailments ranging from acute pain to colic, heart disease, earaches, cholera, whooping cough, hemorrhoids, hysteria, and mumps were prescribed morphine and opium. A survey of Boston’s drugstores published in an 1888 issue of Popular Science Monthly documents the ubiquity of these narcotics: of 10,200 prescriptions reviewed, 1,481,or 14.5 percent, contained an opiate. During this period in the United States and abroad, the abuse of addictive drugs such as opium, morphine, and, soon after it was introduced to the public, cocaine constituted a major public health problem.

***

No evidence has been found to demonstrate that William Halsted and Sigmund Freud ever met. Separated by physical and cultural oceans, their lives were, nevertheless, intricately braided and shaped by a handful of scientific papers on the medicinal uses of cocaine. For Sigmund Freud, the medical profession’s creation of so many morphine addicts led him to experiment with cocaine as a potential antidote. In the quest to obliterate the pain incurred by the surgeon’s craft, William Halsted explored the drug as a safer form of anesthesia. But because cocaine was such a relatively new drug during this period, neither Freud nor Halsted recognized its addictive and deleterious force until it was much too late. By using themselves as guinea pigs in their research, each became dependent upon a substance that nearly destroyed their lives and the work that ultimately changed how we think, live, and heal.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A tour de force of scientific and social history, one that helps illuminate a unique period in the long story of medical discovery. . . . Absorbing and thoroughly documented . . . a vivid narrative of two of the most remarkable of the many contributors to our understanding of human biology and function.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Incisive. . . . An irresistible cautionary tale.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Terrific. . . . This rich, engrossing book reminds us of the strangeness of even heroic destinies.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Markel creates rich portraits of men who shared, as he writes of Freud, a 'particular constellation of bold risk taking, emotional scar tissue, and psychic turmoil.'“

—The New Yorker

“A rich, revelatory new book. . . . [Markel is] a careful writer and a tireless researcher, and as a trained physician himself, Markel is able to pronounce on medical matters with firmness and authority.”

—TIME

“A splendid history . . . [Markel is a] fluent, incisive and often subtly funny writer.”

—The Baltimore Sun

“Provocative . . . persuasive and engrossing.”

—Salon.com

"Compelling and compassionate . . . a book that profoundly demonstrates the complexity and breadth of their genius . . . a richly woven analysis complete with anecdotes, historical research, photos and present-day knowledge about the character of the addictive personality."

—Booklist

“From the dramatic opening scene on the first page to the epilogue, An Anatomy of Addiction is a hugely satisfying read. Howard Markel is physician, historian and wonderful storyteller, and since his tale involves two of the most compelling characters in medicine, I could not put it down—addictive is the word for this terrific book.”

—Abraham Verghese, author of Cutting for Stone

“It’s a fascinating book about fascinating men, but even more interesting for those of us who want a glimpse of modern medicine when it was just starting to develop.”

—The New Republic

“Dr. Markel braids these men’s stories intricately, intelligently and often elegantly.”

—The New York Times

“Markel brilliantly describes the paradox of [Halsted’s and Freud’s] lives.”

—Nature

“Inspired, entertaining and informative . . . [Markel] tells this fascinating tale in an insightful contemporary book that is both intellectually engaging and exceptionally well written.”

—Journal of the American Medical Association

“[A] witty, wide-ranging book.”

—Boston Globe

“A richly engaging book . . . highly recommended.”

—Wired

“Well-researched. . . . A thoughtful picture of late 19th century medicine.”

—The San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

“Colorful study . . . brisk . . . an engaging well-researched historical homily about fame and foible.”

—Bloomberg

“A fascinating revelation of conditions prevailing in hospitals and medical circles in the late 19th and 20th centuries.”

—New York Journal of Books

“The best medical histories are the ones that cause the imagination to run riot. A fast-rising master of satisfying this human quest for mind-altering willies is the Michigan medical historian Howard Markel.”

—The Winnipeg Free Press

“With both wit and style, Markel has produced a scrupulously researched, meticulously detailed account of the history of cocaine, as well as the drug dependences of Halsted and Freud.”

—Hopkins Medicine Magazine

—The New York Times Book Review

“Incisive. . . . An irresistible cautionary tale.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Terrific. . . . This rich, engrossing book reminds us of the strangeness of even heroic destinies.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Markel creates rich portraits of men who shared, as he writes of Freud, a 'particular constellation of bold risk taking, emotional scar tissue, and psychic turmoil.'“

—The New Yorker

“A rich, revelatory new book. . . . [Markel is] a careful writer and a tireless researcher, and as a trained physician himself, Markel is able to pronounce on medical matters with firmness and authority.”

—TIME

“A splendid history . . . [Markel is a] fluent, incisive and often subtly funny writer.”

—The Baltimore Sun

“Provocative . . . persuasive and engrossing.”

—Salon.com

"Compelling and compassionate . . . a book that profoundly demonstrates the complexity and breadth of their genius . . . a richly woven analysis complete with anecdotes, historical research, photos and present-day knowledge about the character of the addictive personality."

—Booklist

“From the dramatic opening scene on the first page to the epilogue, An Anatomy of Addiction is a hugely satisfying read. Howard Markel is physician, historian and wonderful storyteller, and since his tale involves two of the most compelling characters in medicine, I could not put it down—addictive is the word for this terrific book.”

—Abraham Verghese, author of Cutting for Stone

“It’s a fascinating book about fascinating men, but even more interesting for those of us who want a glimpse of modern medicine when it was just starting to develop.”

—The New Republic

“Dr. Markel braids these men’s stories intricately, intelligently and often elegantly.”

—The New York Times

“Markel brilliantly describes the paradox of [Halsted’s and Freud’s] lives.”

—Nature

“Inspired, entertaining and informative . . . [Markel] tells this fascinating tale in an insightful contemporary book that is both intellectually engaging and exceptionally well written.”

—Journal of the American Medical Association

“[A] witty, wide-ranging book.”

—Boston Globe

“A richly engaging book . . . highly recommended.”

—Wired

“Well-researched. . . . A thoughtful picture of late 19th century medicine.”

—The San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

“Colorful study . . . brisk . . . an engaging well-researched historical homily about fame and foible.”

—Bloomberg

“A fascinating revelation of conditions prevailing in hospitals and medical circles in the late 19th and 20th centuries.”

—New York Journal of Books

“The best medical histories are the ones that cause the imagination to run riot. A fast-rising master of satisfying this human quest for mind-altering willies is the Michigan medical historian Howard Markel.”

—The Winnipeg Free Press

“With both wit and style, Markel has produced a scrupulously researched, meticulously detailed account of the history of cocaine, as well as the drug dependences of Halsted and Freud.”

—Hopkins Medicine Magazine