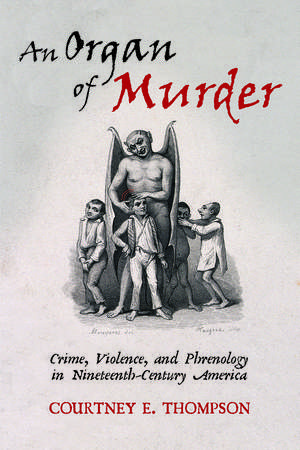

An Organ of Murder: Crime, Violence, and Phrenology in Nineteenth-Century America: Critical Issues in Health and Medicine

Autor Courtney E. Thompsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 feb 2021 – vârsta ani

Finalist for the 2022 Cheiron Book Prize

An Organ of Murder explores the origins of both popular and elite theories of criminality in the nineteenth-century United States, focusing in particular on the influence of phrenology. In the United States, phrenology shaped the production of medico-legal knowledge around crime, the treatment of the criminal within prisons and in public discourse, and sociocultural expectations about the causes of crime. The criminal was phrenology’s ideal research and demonstration subject, and the courtroom and the prison were essential spaces for the staging of scientific expertise. In particular, phrenology constructed ways of looking as well as a language for identifying, understanding, and analyzing criminals and their actions. This work traces the long-lasting influence of phrenological visual culture and language in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical uses of phrenology in courts, prisons, and daily life.

An Organ of Murder explores the origins of both popular and elite theories of criminality in the nineteenth-century United States, focusing in particular on the influence of phrenology. In the United States, phrenology shaped the production of medico-legal knowledge around crime, the treatment of the criminal within prisons and in public discourse, and sociocultural expectations about the causes of crime. The criminal was phrenology’s ideal research and demonstration subject, and the courtroom and the prison were essential spaces for the staging of scientific expertise. In particular, phrenology constructed ways of looking as well as a language for identifying, understanding, and analyzing criminals and their actions. This work traces the long-lasting influence of phrenological visual culture and language in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical uses of phrenology in courts, prisons, and daily life.

Din seria Critical Issues in Health and Medicine

-

Preț: 267.58 lei

Preț: 267.58 lei -

Preț: 220.94 lei

Preț: 220.94 lei - 5%

Preț: 242.73 lei

Preț: 242.73 lei -

Preț: 184.80 lei

Preț: 184.80 lei - 5%

Preț: 241.70 lei

Preț: 241.70 lei - 5%

Preț: 314.84 lei

Preț: 314.84 lei - 5%

Preț: 292.48 lei

Preț: 292.48 lei - 5%

Preț: 318.35 lei

Preț: 318.35 lei - 5%

Preț: 311.37 lei

Preț: 311.37 lei - 5%

Preț: 1076.59 lei

Preț: 1076.59 lei -

Preț: 287.45 lei

Preț: 287.45 lei - 5%

Preț: 270.90 lei

Preț: 270.90 lei -

Preț: 315.48 lei

Preț: 315.48 lei - 5%

Preț: 293.77 lei

Preț: 293.77 lei - 5%

Preț: 427.88 lei

Preț: 427.88 lei - 5%

Preț: 1078.40 lei

Preț: 1078.40 lei - 5%

Preț: 296.39 lei

Preț: 296.39 lei - 5%

Preț: 288.29 lei

Preț: 288.29 lei - 5%

Preț: 298.62 lei

Preț: 298.62 lei -

Preț: 309.24 lei

Preț: 309.24 lei - 5%

Preț: 298.77 lei

Preț: 298.77 lei -

Preț: 312.59 lei

Preț: 312.59 lei -

Preț: 286.30 lei

Preț: 286.30 lei - 5%

Preț: 275.82 lei

Preț: 275.82 lei - 5%

Preț: 305.79 lei

Preț: 305.79 lei - 5%

Preț: 1079.33 lei

Preț: 1079.33 lei - 5%

Preț: 300.35 lei

Preț: 300.35 lei - 5%

Preț: 290.87 lei

Preț: 290.87 lei - 5%

Preț: 409.20 lei

Preț: 409.20 lei -

Preț: 259.42 lei

Preț: 259.42 lei -

Preț: 305.55 lei

Preț: 305.55 lei - 5%

Preț: 314.32 lei

Preț: 314.32 lei - 5%

Preț: 262.95 lei

Preț: 262.95 lei - 5%

Preț: 277.67 lei

Preț: 277.67 lei - 5%

Preț: 302.64 lei

Preț: 302.64 lei - 5%

Preț: 280.06 lei

Preț: 280.06 lei

Preț: 282.52 lei

Preț vechi: 297.39 lei

-5% Nou

Puncte Express: 424

Preț estimativ în valută:

54.08€ • 55.65$ • 45.59£

54.08€ • 55.65$ • 45.59£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781978813069

ISBN-10: 1978813066

Pagini: 278

Ilustrații: 18 b-w images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Rutgers University Press

Colecția Rutgers University Press

Seria Critical Issues in Health and Medicine

ISBN-10: 1978813066

Pagini: 278

Ilustrații: 18 b-w images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Rutgers University Press

Colecția Rutgers University Press

Seria Critical Issues in Health and Medicine

Notă biografică

COURTNEY E. THOMPSON is an assistant professor of the history of science and medicine and U.S. women’s history at Mississippi State University in Starkville. She received her Ph.D. from the program in the history of science and medicine of Yale University in 2015.

Extras

Introduction:

Through a Mirror, Darkly

The phrenologist Lorenzo Fowler had a meeting scheduled for an autumn day in 1849. Rather than viewing his subject in the comfort of his office, he ventured out onto the streets of New York City. He traveled half a mile from Clinton Hall to the New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention, colloquially known as the Tombs, where the warden, who had written to invite the phrenologist on this occasion, welcomed him to the institution. Perhaps he received a tour of the prison with the warden, but the main event was the set of “test examinations” conducted by Fowler on three prisoners. The warden maintained a “studied silence” as Fowler examined each of his subjects in turn, writing down his descriptions of their characters and phrenological characteristics. Only then were the identities and the charges against these prisoners revealed, with the correspondence between this data and their crimes standing as proof of the “triumphant success of phrenological truth.”[1]

When one imagines the phrenological encounter, one often thinks first of a client paying for a reading as a combination of self-help and amusement, an image that is part of our cultural lexicon, captured in popular imagery and satirical accounts. Fowler’s trip to the prison at first glance appears to be an inverted image, a dark mirror to the phrenological visit. Few would suspect that at the same time as phrenologists were being paid to examine men, women, and children in their offices and in tours of the country, they were also paying close attention to and examining another population: convicted criminals in prisons. Indeed, the criminal was more essential for the development of phrenological theory and practice than the paying client, central to both the self-conception of the phrenologist and the development and articulation of phrenological theory.

***

Phrenology, the science of reading the shape of the skull to interpret and predict powers of mind and character, has a rich history and historiography.[2] As early as 1933, Robert Riegel argued that, “contrary to common belief, phrenology did not originate as the scheme of money-making fakers, but from the study of able men using the best scientific methods of their day.”[3] The scientific nature of phrenology, and its place within the history of science, has been well established by historians. Beginning in the 1970s, scholars including Geoffrey Cantor, Roger Cooter, and Steven Shapin closely analyzed the social structures, cultural meaning, and scientific status of phrenology, particularly in the British context. Their debates about the development and meaning of phrenology, its social and intellectual status, and its techniques continued to inform historians of science over the next fifty years.

Why have historians of science and medicine returned again and again to phrenology? The same features which draw historians account in part for the fascination it held for practitioners, commentators, and clients nearly two centuries ago. Phrenology was capacious in its meanings, porous in its boundaries, flexible in its interpretations, and adaptive to various applications. Phrenology was a mirror reflecting that which observers most desired—or most feared—to see, in themselves, in others, in science, and in society. As such, historians have also contemplated this prismatic mirror, analyzing the various images it has produced, considering how phrenology reflected and refracted social concerns about topics like gender, race, reform, education, and the nature of scientific inquiry itself.

The mirror of phrenology also offers another, darker side. While many historians have remarked on the utopian side of phrenology—its reformist ethos and applications, its uses by clients for self-improvement, and so forth—phrenology also reflected a negative image of such utopian visions. Phrenology not only promised to perfect or improve the human race, but simultaneously suggested that not all minds were capable of perfection or improvement. Phrenology was not just an amusing pastime, nor was it only a matter of theoretical debate for elite scientists about the nature of science itself. There were real stakes to this debate and these practices, particularly for those at the bottom rungs of society.

An Organ of Murder examines the ways in which the criminal and criminality became central objects of phrenological research, theory, and public discourse from its origins in Gall’s Schädellehre at the turn of the nineteenth century to its efflorescence and decline in midcentury American practical phrenology. I argue that a primary theme associated with phrenology at each stage of its history was a focus on the problem of crime and the criminal. In the United States, phrenology shaped the production of medico-legal knowledge around crime, the treatment of the criminal, and sociocultural expectations about the causes of crime. Phrenologists made the criminal a central figure for their work and thus a primary tool for the articulation and dissemination of their science. The criminal was the research and demonstration subject par excellence for the spread of phrenology, and the courtroom, the prison, and the gallows were essential spaces for the staging of scientific expertise.

In particular, phrenological ideas helped to construct ways of looking alongside modes of language for identifying, understanding, and analyzing criminals and their actions. These ways of seeing and describing were subsequently translated from the realm of phrenology and into both popular and elite conceptions of criminal behavior.[4] Decades before the “invention” of criminal anthropology by Cesare Lombroso in the 1870s, phrenologists were using visual evidence of facial and cranial anatomy to explain the potential of individuals for violence and criminality, and this discourse also inflected popular uses of visual judgment. Phrenological language around the causes and nature of criminality not only structured mid-nineteenth century medico-legal approaches to the problem of violent crime, but continue to hold a place in our modern lexicon. These two vocabularies—lexical and visual—enabled criminal profiling avant la lettre. Both phrenological language and images of criminality remain a ghost in the machinery of the contemporary carceral state.

This study is centered on the nineteenth-century United States, with a focus on the decades of the 1830s through the 1850s. These decades were crucial for the development of phrenology in the United States, including the rise of phrenology as an elite intellectual pursuit among learned professionals, the emergence of practical phrenology and decline of elite phrenology, and the heyday of practical phrenology in America, set against the political, social, and cultural currents of antebellum period. This book draws a distinction between two cohorts of phrenologists and their respective eras of influence in America. First, I identify a group of educated and professional men, particularly physicians, lawyers, and professors, who orchestrated the introduction of phrenology into American intellectual circles during the 1820s and 1830s. These men established the earliest phrenological societies and journals in the United States, and they sought in phrenology a body of knowledge that could be applied to their respective professional fields, especially medicine, even as these professional fields experienced challenges to their expert status in this period.[5] In contrast to these phrenological enthusiasts stood another group, proponents of a new variety of phrenology that was emerging by the early 1840s: practical phrenologists, as they named themselves, were phrenologists by trade. Rather than attempting to speak to an educated elite, they instead focused on a popular audience as itinerant lecturers who “read” heads for a fee. After the decline of elite phrenology by the beginning of the 1840s, this group of practical phrenologists became the face of phrenology in the United States, contributing to longstanding misapprehensions about the nature of phrenology in the nineteenth century.

Much has been written about phrenology in Europe and in Britain, due to its Continental origins and the role of Scottish and English phrenologists in popularizing the science in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. In the United States, the profound enthusiasm of early adopters matched that of British phrenologists, and the midcentury turn to practical phrenology made the science all the more prevalent and culturally influential in America. Within this context, phrenological approaches to crime and punishment, whether practical, rhetorical, or cultural, were put to use and became common currency. For example, in the United States prison officials frequently invited phrenologists into prisons, and phrenologists and enthusiasts were called to serve as expert witnesses on the stand. Phrenology from its inception spoke to the problems of crime, but the applications of the science to this problem were more successful and longer-lived in the United States. The unique circumstances by which American phrenology was adopted, promulgated, and popularized contributed to its ability to move from theory to practice, especially in the realms of law and penology.

As with many histories of nineteenth-century medicine and science, this story about American phrenology must be told through a partially transnational lens: American phrenology could not have existed without its Continental and British progenitors. American phrenological enthusiasts, practical phrenologists, and phrenological clients alike responded throughout the century to intercontinental crosscurrents, and this transnational movement of ideas, people, objects, texts, and capital is a central part of my study. Further, the engagement of American phrenologists over the course of the century with European scientific developments are also part of this story, particularly how phrenologists reacted to late-century innovations in criminal theory.

Little attention has been paid to the role of phrenology in American criminal jurisprudence and penology.[6] This book demonstrates that phrenology, both elite phrenological enthusiasm and practical phrenology, had much to say about these subjects, influencing the development of various approaches to crime in American medicine, law, and culture. In particular, I illuminate the concurrent development of approaches to medical jurisprudence in 1830s America and the rise of elite phrenological enthusiasm in medico-legal circles in this period. This book demonstrates the deep-seated commitment to and influence of phrenological theory amongst medico-legal experts, especially Isaac Ray, and thus locates phrenology in the history of medical jurisprudence and the insanity defense.[7]

This project also decenters the traditional history of criminology, which has located its origins in 1870s Continental positivism, by positioning phrenology as more than a precursor to theories of the criminal mind.[8] The majority of the history of criminology has focused on the post-1870s positivist moment, instigated by the Italian criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso’s theories of degeneracy, which in turn were inspired by Charles Darwin’s theories of heredity.[9] I suggest that phrenological criminology as it developed within American phrenology and popular culture was a coherent and consistent set of theories and practices that pre-dated the “invention” of criminology in the 1870s.

By tracing the long-lasting influence of phrenological language and imagery in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical application of phrenology in courts and prisons, I complicate considerations of phrenology in American history. I demonstrate that the elite intellectuals of the 1830s were as influential in medico-legal arenas as the practical phrenologists of midcentury proved to be in popular culture, and moreover that both groups were invested in issues of crime and punishment as a means for demonstrating the utility of phrenology and advancing their own claims to expertise over criminal matters. This project thus intervenes in the history of phrenology, exploring its influence in American medico-legal thought, particularly with regard to questions of criminal insanity and medical jurisprudence, as well as in the history of criminology, penology, and popular culture.

Phrenology was not just a scientific curiosity or a precursor to positivist criminology, but rather a robust system of criminal science in its own right. This work traces the long-lasting influence of phrenological visual culture and language in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical uses of phrenology in courts, prisons, and daily life. I further demonstrate the seriousness with which educated phrenological enthusiasts took up phrenology in the early-nineteenth-century United States, with particular attention to the utility they found in phrenology for solving the problem of crime. As I argue in this book, the early adopters of phrenology in Jacksonian America were physicians, professors, and legal experts, and their embrace of this science constituted what I term a “phrenological impulse.” This desire to apply phrenological theories, language, and practices to find practical solutions to social problems had a profound and enduring effect on the development of medical jurisprudence, theories of criminal insanity, and approaches to prison reform in nineteenth-century America. This book extends and reconsiders the history of medical jurisprudence and criminal science, along with the history of phrenology. In so doing, I consider the making of expert knowledge within, and the relationships between, the realms of medicine, law, and scientific practice in nineteenth-century America, as well as the place of both elite and popular science in American culture.

***

An Organ of Murder is organized chronologically, moving from the first decades of the nineteenth century through the turn of the twentieth century. The first chapter re-examines the history of the origins of phrenology in Continental Europe and the United Kingdom between 1805 and the 1820s, focusing on the role of criminals and the prison in the development of early phrenological theory. This chapter begins with a reconsideration of Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, demonstrating the extent to which the prison was used as a laboratory for the articulation of phrenological theory. Next, I discuss the interventions of the Combe brothers, particularly George Combe’s writings on the nature of criminal responsibility. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the criminal theory contained within phrenology, discussing the identification of an “organ of murder” and language of the criminal propensities. I describe how these were “read” visually on the head, and how the language of organs and propensities became tied to the problem of crime. This chapter establishes the extent to which criminals and penal spaces were foundational for and essential to phrenology.

The second chapter shows how phrenology was introduced to the United States in the 1820s and early 1830s, particularly the connections built across the Atlantic between two different phrenological communities. The chapter first traces the founding of the first phrenological societies in the United States and the work of the earliest converts, particularly Charles Caldwell. Second, the chapter explores a transatlantic debate about the validity of phrenology, which focused on the skulls and characters of famous murderers, especially Burke and Hare, and in which American phrenological knowledge was mobilized as part of a British debate. I next discuss the journey of Spurzheim to the United States, which directly resulted in the founding of the Boston Phrenological Society. This Society would become the locus of phrenological enthusiasm in the United States, as these elite, educated, urban professionals saw in phrenology the potential to undergird their expertise in their given fields. Finally, I explore the phrenological cabinets of the Boston and Edinburgh societies, discussing the extent to which they incorporated criminality into their cabinets and the transatlantic networks required to build these spaces.

The third and fourth chapters cover the development of phrenology in the 1830s and 1840s United States in two sites, the courtroom and the prison, and among two cohorts of phrenological adherents, elite phrenological enthusiasts and practical phrenologists. The third chapter focuses on the uses of phrenological theory and language in the realm of medical jurisprudence between the mid-1830s and 1850s. Phrenology emerged in this period as one possibility for crafting medico-legal expertise, particularly on the topic of criminal insanity. This chapter begins by contextualizing medical jurisprudence in early America; at the same time that phrenology was gaining ground in the United States, theories of medical jurisprudence were in flux. I next turn to Isaac Ray, a central figure for the development of theories of medical jurisprudence in the United States, and the work of other phrenological enthusiasts in the realm of medical jurisprudence. Ray’s work, particularly his Treatise on the Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity (1838), helped to introduce phrenological language and ideas into American courtrooms. This chapter concludes with an exploration of court cases in which attorneys, judges, and expert witnesses made implicit or explicit use of phrenological theories. These cases of “phrenology on trial” suggest both the uses of phrenology for the building of medico-legal expertise and the extent to which phrenological language around the propensities was incorporated into the nature of criminal responsibility.

The fourth chapter explores the relationship between American phrenology and the penal system from the mid-1830s through the 1850s. This chapter engages with practical phrenology, focusing on the tension between the anti-capital punishment and reformist ideology broadly promoted by practical phrenologists and the simultaneous necessity of the prison and the gallows for the production of phrenological materials and capital. This chapter begins with a discussion of the broad context of the reformist impulse in American culture and in the variation of practical phrenology promoted by the Fowler brothers. Next, the chapter discusses visits by American phrenologists to prisons, which they used as testing sites to promote the truth of their science, and the extent to which phrenologists participated in pre- and post-execution examinations of convicts. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the inherent tension between discourse and practice: phrenologists decried the horrors of capital punishment, but required access to the heads and skulls that were its fruits.

The fifth chapter focuses on the midcentury popular culture of practical phrenology in the home and the urban landscape. I relate the popularity of phrenological messages about criminal potential to broader social anxieties about strangers, immigration, mobility, and danger in the antebellum city and discourses about policing. This chapter first develops the dichotomy between “good” and “bad” heads, which juxtaposed great men and notorious villains and was prevalent in popular phrenological writing. Next, I explore how this lesson was interpreted for daily use, especially anxieties about self-improvement and the potential of children. Beyond practical uses of the maxims of phrenology, this chapter also discusses fictional fantasies of the perfect prediction of “phrenological detectives” to catch criminals before (or shortly after) the act. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the racialization of criminality in the postbellum period, discussing the extent to which phrenology participated in this shifting narrative about criminal types. This chapter reflects on the ways in which phrenological ways of seeing inflected both self-knowledge and midcentury attempts to know others in a “world of strangers.”

The sixth chapter turns to the final third of the nineteenth century, discussing the development of new fields of criminal science through the lens of phrenological reception. This chapter begins with a discussion of the development of the neuro disciplines as framed within a dichotomy of “old” and “new” phrenology, exploring how phrenologists and critics alike interpreted the genealogy of these sciences. The next two sections address the criminal sciences of Cesare Lombroso and Alphonse Bertillon respectively, focusing in particular on the continuities between these “new” sciences and phrenological tradition, and on the ways in which phrenologists responded to these developments, viewing them as an extension of their own practices.

The epilogue considers the afterlives of this phrenological impulse in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as well as the phrenological futures inspired by the traces of this epistemology. I discuss the demise of the phrenological profession and the last case of phrenology in court, the 1928 murder trial of Eula Mae Thompson in Georgia. I then address recent developments in criminology, particularly attempts to identify a “criminal gene” and the use of fMRIs to identify the criminal mind. The epilogue considers the longevity of phrenological language and images of the criminal, suggesting that phrenological concepts continue to inflect how we think about, describe, and attempt to solve crime in the present day.

Notes to the Introduction

Through a Mirror, Darkly

The phrenologist Lorenzo Fowler had a meeting scheduled for an autumn day in 1849. Rather than viewing his subject in the comfort of his office, he ventured out onto the streets of New York City. He traveled half a mile from Clinton Hall to the New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention, colloquially known as the Tombs, where the warden, who had written to invite the phrenologist on this occasion, welcomed him to the institution. Perhaps he received a tour of the prison with the warden, but the main event was the set of “test examinations” conducted by Fowler on three prisoners. The warden maintained a “studied silence” as Fowler examined each of his subjects in turn, writing down his descriptions of their characters and phrenological characteristics. Only then were the identities and the charges against these prisoners revealed, with the correspondence between this data and their crimes standing as proof of the “triumphant success of phrenological truth.”[1]

When one imagines the phrenological encounter, one often thinks first of a client paying for a reading as a combination of self-help and amusement, an image that is part of our cultural lexicon, captured in popular imagery and satirical accounts. Fowler’s trip to the prison at first glance appears to be an inverted image, a dark mirror to the phrenological visit. Few would suspect that at the same time as phrenologists were being paid to examine men, women, and children in their offices and in tours of the country, they were also paying close attention to and examining another population: convicted criminals in prisons. Indeed, the criminal was more essential for the development of phrenological theory and practice than the paying client, central to both the self-conception of the phrenologist and the development and articulation of phrenological theory.

***

Phrenology, the science of reading the shape of the skull to interpret and predict powers of mind and character, has a rich history and historiography.[2] As early as 1933, Robert Riegel argued that, “contrary to common belief, phrenology did not originate as the scheme of money-making fakers, but from the study of able men using the best scientific methods of their day.”[3] The scientific nature of phrenology, and its place within the history of science, has been well established by historians. Beginning in the 1970s, scholars including Geoffrey Cantor, Roger Cooter, and Steven Shapin closely analyzed the social structures, cultural meaning, and scientific status of phrenology, particularly in the British context. Their debates about the development and meaning of phrenology, its social and intellectual status, and its techniques continued to inform historians of science over the next fifty years.

Why have historians of science and medicine returned again and again to phrenology? The same features which draw historians account in part for the fascination it held for practitioners, commentators, and clients nearly two centuries ago. Phrenology was capacious in its meanings, porous in its boundaries, flexible in its interpretations, and adaptive to various applications. Phrenology was a mirror reflecting that which observers most desired—or most feared—to see, in themselves, in others, in science, and in society. As such, historians have also contemplated this prismatic mirror, analyzing the various images it has produced, considering how phrenology reflected and refracted social concerns about topics like gender, race, reform, education, and the nature of scientific inquiry itself.

The mirror of phrenology also offers another, darker side. While many historians have remarked on the utopian side of phrenology—its reformist ethos and applications, its uses by clients for self-improvement, and so forth—phrenology also reflected a negative image of such utopian visions. Phrenology not only promised to perfect or improve the human race, but simultaneously suggested that not all minds were capable of perfection or improvement. Phrenology was not just an amusing pastime, nor was it only a matter of theoretical debate for elite scientists about the nature of science itself. There were real stakes to this debate and these practices, particularly for those at the bottom rungs of society.

An Organ of Murder examines the ways in which the criminal and criminality became central objects of phrenological research, theory, and public discourse from its origins in Gall’s Schädellehre at the turn of the nineteenth century to its efflorescence and decline in midcentury American practical phrenology. I argue that a primary theme associated with phrenology at each stage of its history was a focus on the problem of crime and the criminal. In the United States, phrenology shaped the production of medico-legal knowledge around crime, the treatment of the criminal, and sociocultural expectations about the causes of crime. Phrenologists made the criminal a central figure for their work and thus a primary tool for the articulation and dissemination of their science. The criminal was the research and demonstration subject par excellence for the spread of phrenology, and the courtroom, the prison, and the gallows were essential spaces for the staging of scientific expertise.

In particular, phrenological ideas helped to construct ways of looking alongside modes of language for identifying, understanding, and analyzing criminals and their actions. These ways of seeing and describing were subsequently translated from the realm of phrenology and into both popular and elite conceptions of criminal behavior.[4] Decades before the “invention” of criminal anthropology by Cesare Lombroso in the 1870s, phrenologists were using visual evidence of facial and cranial anatomy to explain the potential of individuals for violence and criminality, and this discourse also inflected popular uses of visual judgment. Phrenological language around the causes and nature of criminality not only structured mid-nineteenth century medico-legal approaches to the problem of violent crime, but continue to hold a place in our modern lexicon. These two vocabularies—lexical and visual—enabled criminal profiling avant la lettre. Both phrenological language and images of criminality remain a ghost in the machinery of the contemporary carceral state.

This study is centered on the nineteenth-century United States, with a focus on the decades of the 1830s through the 1850s. These decades were crucial for the development of phrenology in the United States, including the rise of phrenology as an elite intellectual pursuit among learned professionals, the emergence of practical phrenology and decline of elite phrenology, and the heyday of practical phrenology in America, set against the political, social, and cultural currents of antebellum period. This book draws a distinction between two cohorts of phrenologists and their respective eras of influence in America. First, I identify a group of educated and professional men, particularly physicians, lawyers, and professors, who orchestrated the introduction of phrenology into American intellectual circles during the 1820s and 1830s. These men established the earliest phrenological societies and journals in the United States, and they sought in phrenology a body of knowledge that could be applied to their respective professional fields, especially medicine, even as these professional fields experienced challenges to their expert status in this period.[5] In contrast to these phrenological enthusiasts stood another group, proponents of a new variety of phrenology that was emerging by the early 1840s: practical phrenologists, as they named themselves, were phrenologists by trade. Rather than attempting to speak to an educated elite, they instead focused on a popular audience as itinerant lecturers who “read” heads for a fee. After the decline of elite phrenology by the beginning of the 1840s, this group of practical phrenologists became the face of phrenology in the United States, contributing to longstanding misapprehensions about the nature of phrenology in the nineteenth century.

Much has been written about phrenology in Europe and in Britain, due to its Continental origins and the role of Scottish and English phrenologists in popularizing the science in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. In the United States, the profound enthusiasm of early adopters matched that of British phrenologists, and the midcentury turn to practical phrenology made the science all the more prevalent and culturally influential in America. Within this context, phrenological approaches to crime and punishment, whether practical, rhetorical, or cultural, were put to use and became common currency. For example, in the United States prison officials frequently invited phrenologists into prisons, and phrenologists and enthusiasts were called to serve as expert witnesses on the stand. Phrenology from its inception spoke to the problems of crime, but the applications of the science to this problem were more successful and longer-lived in the United States. The unique circumstances by which American phrenology was adopted, promulgated, and popularized contributed to its ability to move from theory to practice, especially in the realms of law and penology.

As with many histories of nineteenth-century medicine and science, this story about American phrenology must be told through a partially transnational lens: American phrenology could not have existed without its Continental and British progenitors. American phrenological enthusiasts, practical phrenologists, and phrenological clients alike responded throughout the century to intercontinental crosscurrents, and this transnational movement of ideas, people, objects, texts, and capital is a central part of my study. Further, the engagement of American phrenologists over the course of the century with European scientific developments are also part of this story, particularly how phrenologists reacted to late-century innovations in criminal theory.

Little attention has been paid to the role of phrenology in American criminal jurisprudence and penology.[6] This book demonstrates that phrenology, both elite phrenological enthusiasm and practical phrenology, had much to say about these subjects, influencing the development of various approaches to crime in American medicine, law, and culture. In particular, I illuminate the concurrent development of approaches to medical jurisprudence in 1830s America and the rise of elite phrenological enthusiasm in medico-legal circles in this period. This book demonstrates the deep-seated commitment to and influence of phrenological theory amongst medico-legal experts, especially Isaac Ray, and thus locates phrenology in the history of medical jurisprudence and the insanity defense.[7]

This project also decenters the traditional history of criminology, which has located its origins in 1870s Continental positivism, by positioning phrenology as more than a precursor to theories of the criminal mind.[8] The majority of the history of criminology has focused on the post-1870s positivist moment, instigated by the Italian criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso’s theories of degeneracy, which in turn were inspired by Charles Darwin’s theories of heredity.[9] I suggest that phrenological criminology as it developed within American phrenology and popular culture was a coherent and consistent set of theories and practices that pre-dated the “invention” of criminology in the 1870s.

By tracing the long-lasting influence of phrenological language and imagery in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical application of phrenology in courts and prisons, I complicate considerations of phrenology in American history. I demonstrate that the elite intellectuals of the 1830s were as influential in medico-legal arenas as the practical phrenologists of midcentury proved to be in popular culture, and moreover that both groups were invested in issues of crime and punishment as a means for demonstrating the utility of phrenology and advancing their own claims to expertise over criminal matters. This project thus intervenes in the history of phrenology, exploring its influence in American medico-legal thought, particularly with regard to questions of criminal insanity and medical jurisprudence, as well as in the history of criminology, penology, and popular culture.

Phrenology was not just a scientific curiosity or a precursor to positivist criminology, but rather a robust system of criminal science in its own right. This work traces the long-lasting influence of phrenological visual culture and language in American culture, law, and medicine, as well as the practical uses of phrenology in courts, prisons, and daily life. I further demonstrate the seriousness with which educated phrenological enthusiasts took up phrenology in the early-nineteenth-century United States, with particular attention to the utility they found in phrenology for solving the problem of crime. As I argue in this book, the early adopters of phrenology in Jacksonian America were physicians, professors, and legal experts, and their embrace of this science constituted what I term a “phrenological impulse.” This desire to apply phrenological theories, language, and practices to find practical solutions to social problems had a profound and enduring effect on the development of medical jurisprudence, theories of criminal insanity, and approaches to prison reform in nineteenth-century America. This book extends and reconsiders the history of medical jurisprudence and criminal science, along with the history of phrenology. In so doing, I consider the making of expert knowledge within, and the relationships between, the realms of medicine, law, and scientific practice in nineteenth-century America, as well as the place of both elite and popular science in American culture.

***

An Organ of Murder is organized chronologically, moving from the first decades of the nineteenth century through the turn of the twentieth century. The first chapter re-examines the history of the origins of phrenology in Continental Europe and the United Kingdom between 1805 and the 1820s, focusing on the role of criminals and the prison in the development of early phrenological theory. This chapter begins with a reconsideration of Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, demonstrating the extent to which the prison was used as a laboratory for the articulation of phrenological theory. Next, I discuss the interventions of the Combe brothers, particularly George Combe’s writings on the nature of criminal responsibility. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the criminal theory contained within phrenology, discussing the identification of an “organ of murder” and language of the criminal propensities. I describe how these were “read” visually on the head, and how the language of organs and propensities became tied to the problem of crime. This chapter establishes the extent to which criminals and penal spaces were foundational for and essential to phrenology.

The second chapter shows how phrenology was introduced to the United States in the 1820s and early 1830s, particularly the connections built across the Atlantic between two different phrenological communities. The chapter first traces the founding of the first phrenological societies in the United States and the work of the earliest converts, particularly Charles Caldwell. Second, the chapter explores a transatlantic debate about the validity of phrenology, which focused on the skulls and characters of famous murderers, especially Burke and Hare, and in which American phrenological knowledge was mobilized as part of a British debate. I next discuss the journey of Spurzheim to the United States, which directly resulted in the founding of the Boston Phrenological Society. This Society would become the locus of phrenological enthusiasm in the United States, as these elite, educated, urban professionals saw in phrenology the potential to undergird their expertise in their given fields. Finally, I explore the phrenological cabinets of the Boston and Edinburgh societies, discussing the extent to which they incorporated criminality into their cabinets and the transatlantic networks required to build these spaces.

The third and fourth chapters cover the development of phrenology in the 1830s and 1840s United States in two sites, the courtroom and the prison, and among two cohorts of phrenological adherents, elite phrenological enthusiasts and practical phrenologists. The third chapter focuses on the uses of phrenological theory and language in the realm of medical jurisprudence between the mid-1830s and 1850s. Phrenology emerged in this period as one possibility for crafting medico-legal expertise, particularly on the topic of criminal insanity. This chapter begins by contextualizing medical jurisprudence in early America; at the same time that phrenology was gaining ground in the United States, theories of medical jurisprudence were in flux. I next turn to Isaac Ray, a central figure for the development of theories of medical jurisprudence in the United States, and the work of other phrenological enthusiasts in the realm of medical jurisprudence. Ray’s work, particularly his Treatise on the Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity (1838), helped to introduce phrenological language and ideas into American courtrooms. This chapter concludes with an exploration of court cases in which attorneys, judges, and expert witnesses made implicit or explicit use of phrenological theories. These cases of “phrenology on trial” suggest both the uses of phrenology for the building of medico-legal expertise and the extent to which phrenological language around the propensities was incorporated into the nature of criminal responsibility.

The fourth chapter explores the relationship between American phrenology and the penal system from the mid-1830s through the 1850s. This chapter engages with practical phrenology, focusing on the tension between the anti-capital punishment and reformist ideology broadly promoted by practical phrenologists and the simultaneous necessity of the prison and the gallows for the production of phrenological materials and capital. This chapter begins with a discussion of the broad context of the reformist impulse in American culture and in the variation of practical phrenology promoted by the Fowler brothers. Next, the chapter discusses visits by American phrenologists to prisons, which they used as testing sites to promote the truth of their science, and the extent to which phrenologists participated in pre- and post-execution examinations of convicts. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the inherent tension between discourse and practice: phrenologists decried the horrors of capital punishment, but required access to the heads and skulls that were its fruits.

The fifth chapter focuses on the midcentury popular culture of practical phrenology in the home and the urban landscape. I relate the popularity of phrenological messages about criminal potential to broader social anxieties about strangers, immigration, mobility, and danger in the antebellum city and discourses about policing. This chapter first develops the dichotomy between “good” and “bad” heads, which juxtaposed great men and notorious villains and was prevalent in popular phrenological writing. Next, I explore how this lesson was interpreted for daily use, especially anxieties about self-improvement and the potential of children. Beyond practical uses of the maxims of phrenology, this chapter also discusses fictional fantasies of the perfect prediction of “phrenological detectives” to catch criminals before (or shortly after) the act. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the racialization of criminality in the postbellum period, discussing the extent to which phrenology participated in this shifting narrative about criminal types. This chapter reflects on the ways in which phrenological ways of seeing inflected both self-knowledge and midcentury attempts to know others in a “world of strangers.”

The sixth chapter turns to the final third of the nineteenth century, discussing the development of new fields of criminal science through the lens of phrenological reception. This chapter begins with a discussion of the development of the neuro disciplines as framed within a dichotomy of “old” and “new” phrenology, exploring how phrenologists and critics alike interpreted the genealogy of these sciences. The next two sections address the criminal sciences of Cesare Lombroso and Alphonse Bertillon respectively, focusing in particular on the continuities between these “new” sciences and phrenological tradition, and on the ways in which phrenologists responded to these developments, viewing them as an extension of their own practices.

The epilogue considers the afterlives of this phrenological impulse in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as well as the phrenological futures inspired by the traces of this epistemology. I discuss the demise of the phrenological profession and the last case of phrenology in court, the 1928 murder trial of Eula Mae Thompson in Georgia. I then address recent developments in criminology, particularly attempts to identify a “criminal gene” and the use of fMRIs to identify the criminal mind. The epilogue considers the longevity of phrenological language and images of the criminal, suggesting that phrenological concepts continue to inflect how we think about, describe, and attempt to solve crime in the present day.

Notes to the Introduction

[1] N. Sizer, “Article LXVII. L.N. Fowler’s Visit to the Tombs,” American Phrenological Journal 11, no. 9 (October 1849): 316-317.

[2] On phrenology, see: Mary A. Armstrong, “Reading a Head: Jane Eyre, Phrenology, and the Homoerotics of Legibility,” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 1 (2005): 107-132; David Bakan, “The Influence of Phrenology on American Psychology,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 2, no. 3 (1966): 200-220; Christopher J. Beshara, “Moral Hospitals, Addled Brains and Cranial Conundrums: Rationalizations of the Criminal Mind in Antebellum America,” Australasian Journal of American Studies 29, no. 1 (2010): 36-60; Carla Bittel, “Testing the Truth of Phrenology: Knowledge Experiments in Antebellum American Cultures of Science and Health,” Medical History 63, no. 3 (2019): 352-374; Carla Bittel, “Woman, Know Thyself: Producing and Using Phrenological Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century America,” Centaurus 55, no. 2 (2013): 104-130; Rhonda Boshears and Harry Whitaker, “Phrenology and Physiognomy in Victorian Literature,” in Literature, Neurology, and Neuroscience: Historical and Literary Connections, ed. Anne Stiles, Stanley Finger, and François Boller (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), 87-112; Susan Branson, “Phrenology and the Science of Race in Antebellum America,” Early American Studies 15, no. 1 (2017): 164-193; Jason W. Brown and Karen L. Chobar, “Phrenological Studies of Aphasia before Broca: Broca’s Aphasia or Gall’s Aphasia?” Brain and Language 43, no. 3 (1992): 475-486; G. N. Cantor, “A Critique of Shapin’s Social Interpretation of the Edinburgh Phrenology Debate,” Annals of Science 32, no. 3 (1975): 245-256; G. N. Cantor, “The Edinburgh Phrenology Debate: 1803-1828,” Annals of Science 32, no. 3 (1975): 195-218; Shalyn Claggett, “Putting Character First: The Narrative Construction of Innate Identity in Phrenological Texts,” VIJ: Victorians Institute Journal 38 (2010): 103-126; Charles Colbert, A Measure of Perfection: Phrenology and the Fine Arts in America (Chapel Hill; London: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); Roger Cooter, The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organization of Consent in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984); Roger Cooter, “Phrenology and British Alienists, c. 1825-1845. Part I: Converts to a Doctrine,” Medical History 20, no. 1 (1976): 1-21; Roger Cooter, “Phrenology and British Alienists, c. 1825-1845. Part II: Doctrine and Practice,” Medical History 20, no. 2 (1976): 135-151; Roger Cooter, Phrenology in the British Isles: An Annotated Historical Biobibliography and Index(Metuchen; London: Scarecrow Press, 1989); R. J. Cooter, “Phrenology: The Provocation of Progress,” History of Science 14, no. 4 (1976): 211-234; Tabea Cornel, “Something Old, Something New, Something Pseudo, Something True: Pejorative and Deferential References to Phrenology since 1840,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 161, no. 4 (2017): 299-332; Macdonald Critchley, “Neurology’s Debt to F. J. Gall (1758-1828),” British Medical Journal 2, no. 5465 (1965): 775-781; Nicholas Dames, “The Clinical Novel: Phrenology and Villette,” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 29, no. 3 (1996): 367-390; John D. Davies, Phrenology Fad and Science. A 19th -Century American Crusade (Archon Books: 1971 [1955]); David de Giustino, Conquest of Mind: Phrenology and Victorian Social Thought (London; New York: Routledge, 2016 [1975]); Paul Eling and Stanley Finger, eds., “Gall and Phrenology: New Perspectives,” special issue, Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 29, no. 1 (2020); Stanley Finger and Paul Eling, Franz Joseph Gall: Naturalist of the Mind, Visionary of the Brain (New York: New York University Press, 2019); Samuel H. Greenblatt, “Phrenology in the Science and Culture of the 19th Century,” Neurosurgery 37, no. 4 (1995): 790-805; Jason Y. Hall, “Gall’s Phrenology: A Romantic Psychology,” Studies in Romanticism 16, no. 3 (1977): 305-317; Cynthia S. Hamilton, “‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ Phrenology and Anti-slavery,” Slavery and Abolition 29, no. 2 (2008): 173-187; Victor L. Hilts, “Obeying the Laws of Hereditary Descent: Phrenological Views on Inheritance and Eugenics,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 18, no. 1 (1982): 62-77; Edward Hungerford, “Poe and Phrenology,” American Literature 2, no. 3 (1930): 209-231; Bill Jenkins, “Phrenology, Heredity and Progress in George Combe’s Constitution of Man,” The British Journal for the History of Science 48, no. 3 (2015): 455-473; Enda Leaney, “Phrenology in Nineteenth-Century Ireland,” New Hiberia Review 10, no. 3 (2006): 24-42; Sherrie Lynne Lyons, Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009); Angus McLaren, "Phrenology: Medium and Message," The Journal of Modern History 46, no. 1 (1974): 86-97; Angus McLaren, “A Prehistory of the Social Sciences: Phrenology in France,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 23, no. 1 (1981): 3-22; Patricia S. Noel and Eric T. Carlson, “Origins of the Word ‘Phrenology,’” American Journal of Psychiatry 127, no. 5 (1970): 694-697; T. M. Parssinen, “Popular Science and Society: The Phrenology Movement in Early Victorian Britain,” Journal of Social History 8, no. 1 (1974): 1-20; James Poskett, Materials of the Mind: Phrenology, Race, and the Global History of Science, 1815-1920 (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2019); James Poskett, “Phrenology, Correspondence, and the Global Politics of Reform, 1815-1848,” The Historical Journal 60, no. 2 (2017): 409-442; Marc Renneville, Le langage des crânes: une histoire de la phrénologie (Paris: Institut d'Édition, Sanofi-Synthélabo, 2000); Robert E. Riegel, “The Introduction of Phrenology to the United States,” The American Historical Review 39, no. 1 (1933): 73-78; Cynthia Eagle Russett, Sexual Science: The Victorian Construction of Womanhood (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 1989), 16-48; Steven Shapin, “Phrenological Knowledge and the Social Structure of Early Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh,” Annals of Science 32, no. 3 (1975): 219-243; Steven Shapin, “The Politics of Observation: Cerebral Anatomy and Social Interests in the Edinburgh Phrenology Disputes,” Sociological Review 27 (Special Issue, May 1979): 139-178; Sally Shuttleworth, Charlotte Brontë and Victorian Psychology (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 57-70; Donald Simpson, “Phrenology and the Neurosciences: Contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim,” ANZ Journal of Surgery 75, no. 6 (2005): 475-482; Michael M. Sokal, "Practical Phrenology as Psychological Counseling in the 19th-Century United States," in The Transformation of Psychology: Influences of 19th-Century Philosophy, Technology, and Natural Science, ed. Christopher D. Green, Marlene Shore, and Thomas Teo (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001): 21-44; David Stack, Queen Victoria’s Skull: George Combe and the Mid-Victorian Mind (London; New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2008); Martin Staum, “Physiognomy and Phrenology at the Paris Athénée,” Journal of the History of Ideas 56, no. 3 (1995): 443-462; Madeleine B. Stern, “Emerson and Phrenology,” Studies in the American Renaissance (1984): 213-228; Madeleine B. Stern, Heads & Headlines: The Phrenological Fowlers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971); Madeleine B. Stern, “Mark Twain Had His Head Examined,” American Literature 41, no. 2 (1969): 207-218; Madeleine B. Stern, “Poe: ‘The Mental Temperament’ for Phrenologists,” American Literature 40, no. 2 (1968):155-163; Fenneke Sysling, “Science and Self-Assessment: Phrenological Charts 1840-1940,” British Journal for the History of Science 51, no. 2 (2018): 261-80; Owsei Temkin, “Gall and the Phrenological Movement,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 21, no. 3 (1947): 275-321; Daniel Patrick Thurs, Science Talk: Changing Notions of Science in American Popular Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 22-52; Stephen Tomlinson, Head Masters: Phrenology, Secular Education, and Nineteenth-Century Social Thought (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005); Richard Twine, “Physiognomy, Phrenology and the Temporality of the Body,” Body & Society 8, no. 1 (2002): 67-88; Pieter Verstraete, “The Taming of Disability: Phrenology and Bio-power on the Road to the Destruction of Otherness in France (1800-60),” Journal of the History of Education Society 34, no. 2 (2005): 119-134; Anthony A. Walsh, “The American Tour of Dr. Spurzheim,” The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 27, no. 2 (1972): 187-205; Anthony A. Walsh, “Phrenology and the Boston Medical Community in the 1830s,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 50, no. 2 (1976): 261-273; Kenneth J. Weiss, “Isaac Ray’s Affair with Phrenology,” The Journal of Psychiatry & Law 34, no. 4 (2006): 455-459; Kenneth J. Weiss, “Isaac Ray at 200: Phrenology and Expert Testimony,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 35, no. 3 (2007): 339-345; Christopher G. White, “Minds Intensely Unsettled: Phrenology, Experience, and the American Pursuit of Spiritual Assurance, 1830-1880,” Religion and American Culture 16, no. 2 (2006): 227-261; John B. Wilson, “Phrenology and the Transcendentalists,” American Literature 28, no. 2 (1956): 220-225; John van Wyhe, “The Authority of Human Nature: The Schädellehre of Franz Joseph Gall,” The British Journal for the History of Science 35, no. 1 (2002): 17-42; John van Wyhe, Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2004); John van Wyhe, “Was Phrenology a Reform Science? Towards a New Generalization for Phrenology,” History of Science 42, no. 3 (2004): 313-331; Arthur Wrobel, “Orthodoxy and Respectability in Nineteenth-Century Phrenology,” Journal of Popular Culture 9, no. 1 (1975): 38-50; Robert M. Young, Mind, Brain, and Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century: Cerebral Localization and its Biological Context from Gall to Ferrier (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990 [1970]), 9-53; S. Zola-Morgan, “Localization of Brain Function: The Legacy of Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828),” Annual Review of Neuroscience 18, no. 1 (1995): 359-83.

[3] Riegel, “The Introduction of Phrenology to the United States,” 73.

[4] Phrenology operated alongside other approaches to visual judgment on the basis of appearance in the nineteenth century, especially physiognomy. See: Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1982); Lucy Hartley, Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth-Century Culture (Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001); Christopher J. Lukasik, Discerning Characters: The Culture of Appearance in Early America (Philadelphia; Oxford: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Sharrona Pearl, About Faces: Physiognomy in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2010); Melissa Percival, The Appearance of Character: Physiognomy and Facial Expression in Eighteenth-Century France (London: W. S. Maney & Son Ltd., 1999); Ellis Shookman, ed., The Faces of Physiognomy: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Johann Caspar Lavater, ed. Ellis Shookman(Columbia: Camden House, Inc., 1993).

[5] Walsh referred to this cohort as “scientific phrenologists,” and notes that there was a broader group of educated men, particularly in Boston, who studied phrenology as a leisure activity. Walsh, “Phrenology and the Boston Medical Community,” 271, 273.

[6] On phrenology and crime or criminology, see: Michael Dow Burkhead, The Search for the Causes of Crime: A History of Theory in Criminology (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 67-72; Beshara, “Moral Hospitals, Addled Brains and Cranial Conundrums”; Finger and Eling, Franz Joseph Gall, 382-389; Arthur E. Fink, Causes of Crime: Biological Theories in the United States, 1800-1915 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1938), 1-19; Nicole Hahn Rafter, “The Murderous Dutch Fiddler: Criminology, History, and the Problem of Phrenology,” Theoretical Criminology 9, no. 1 (2005): 65-96; Stern also discusses the Fowler brothers’ attention to penal reform in her work, and Davies includes a chapter on penology in his. Davies, Phrenology Fad and Science, 98-105; Stern, Heads & Headlines, 39-41.

[7] On medical jurisprudence, see: John Starrett Hughes, In the Law’s Darkness: Isaac Ray and the Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oceana Publications, Inc., 1986); R. Gregory Lande, Abraham Man: Madness, Malingering and the Development of Medical Testimony (New York: Algora Publishing, 2012); James C. Mohr, Doctors and the Law: Medical Jurisprudence in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996 [1993]); Daniel N. Robinson, Wild Beasts & Idle Humours: The Insanity Defense from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 1996); Charles E. Rosenberg, The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau: Psychiatry and the Law in the Gilded Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976 [1968]).

[8] For example, David A. Jones’ History of Criminology devotes a mere two pages to phrenology in a book of more than two hundred pages, and focuses exclusively on the work of Gall and Spurzheim and the European context. David A. Jones, History of Criminology: A Philosophical Perspective (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986), 136-137. Arthur Fink and Nicole Hahn Rafter have more to say about the role of phrenology in the history of criminology. See: Fink, Causes of Crime, 1-19; Nicole Hahn Rafter, Creating Born Criminals (Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 75-79, 94; Nicole Rafter, The Criminal Brain: Understanding Biological Theories of Crime (New York: New York University Press, 2008), 40-64; Rafter, “The Murderous Dutch Fiddler.”

[9] On the history of criminology, see: Piers Beirne, Inventing Criminology: Essays on the Rise of Homo Criminalis (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993); Burkhead, The Search for the Causes of Crime; Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2001); Jonathan Finn, Capturing the Criminal Image: From Mug Shot to Surveillance Society (Minneapolis; London: University of Minneapolis Press, 2009); Mary Gibson, Born to Crime: Cesare Lombroso and the Origins of Biological Criminology (Westport; London: Praeger, 2002); Fink, Causes of Crime; David G. Horn, The Criminal Body: Lombroso and the Anatomy of Deviance (New York; London: Routledge, 2003); Jones, History of Criminology; Rafter, Creating Born Criminals; Ysabel Rennie, The Search for Criminal Man: A Conceptual History of the Dangerous Offender (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1978).

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction Through a Mirror, Darkly

1 Origins and Organs

2 Transatlantic Societies and Skulls

3 Phrenology on Trial

4 The Prison as Laboratory

5 Policing the Self and the Stranger

6 A Victory for Phrenology?

Epilogue Phrenological Futures

Notes

Bibliography

Inde

Acknowledgments

Introduction Through a Mirror, Darkly

1 Origins and Organs

2 Transatlantic Societies and Skulls

3 Phrenology on Trial

4 The Prison as Laboratory

5 Policing the Self and the Stranger

6 A Victory for Phrenology?

Epilogue Phrenological Futures

Notes

Bibliography

Inde

Recenzii

"Courtney Thompson provocatively measures the face, head, and soul of American phrenology and invites us to a discovery of the historical origins of scientific criminology."

"In this compelling book, Courtney Thompson takes readers to the prisons, courtrooms, and streets of antebellum cities to expose just how phrenology claimed authority on criminality. Rich in detail and analysis, An Organ of Murder vividly illustrates the long history of making criminal minds and bodies into objects of medical and scientific inquiry."

"This short but informative book will appeal to anyone with an interest in phrenology, criminology, or the histories of psychiatry, psychology, and related fields, especially in nineteenth-century America. It fills a void, is well researched, and is written in an engaging and captivating way."

"For a compelling introduction to what a new generation of scholars is discovering about the perennially interesting topic of phrenology, Courtney E. Thompson’s An Organ of Murder comes highly recommended. This sophisticated, well-written history explores an aspect of phrenology that deserves more attention: its influence on both elite and popular conceptions of criminality....An Organ of Murder should find an appreciative readership not only among historians of science and medicine but also scholars interested in the new carceral history."

"Professor Thompson’s book does what it does quite well. It is an important contribution to the literature. And we might expect that it will be a guide to contemporary legal theory as well. It surely should be."

"Unlike many existing studies of phrenology, which tend to focus on the science’s European fortunes, Thompson takes on the nineteenth-century United States, particularly the period from 1830 to 1860. The book situates phrenology in the history of American criminal justice and the emerging conceptualization of criminality as an innate biological predisposition....Thompson adds a new, distinctively legal note to recent histories of phrenological science."

"An Organ of Murder is a fascinating, well-written history of phrenology....Recommended."

"The book will be of clear interest to those interested in phrenology, but it will also be relevant to scholars working in the history of criminology and punishment. One reason is Thompson's excellent demonstration of phrenology's reliance on the prison, which raises larger questions about criminology's relationship with confinement....An Organ of Murder will prove interesting and helpful to scholars working in the history of criminology and punishment."

"Thompson presents an impressively researched and appealingly structured argument for the importance of crime and punishment to phrenology, that problematic frontrunner of so many human and social sciences."

"This book provides much needed insight into the confluence of phrenology, criminal justice, and the attempts by Americans to better explain, understand, and even correct criminal behavior in the nineteenth century and beyond."

"Vividly narrated with great wit and insight, An Organ of Murder constitutes an important contribution to the history of criminology as well as phrenology, with important implications for the practice of law and the human sciences... Thompson succeeds brilliantly. An Organ of Murder deserves a wide readership among historians and legal scholars, who will readily see the importance of following her leads."

Descriere

An Organ of Murder explores the origins of both popular and elite theories of criminality in the nineteenth-century United States. This work traces the long-lasting influence of phrenological visual culture and language in America, as well as the practical uses of phrenology in courts, prisons, and daily life.