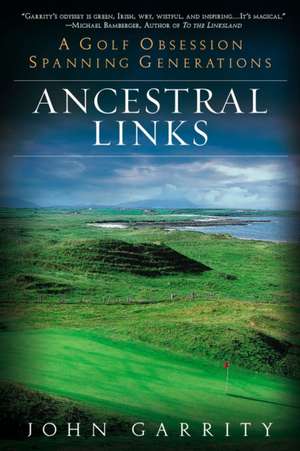

Ancestral Links: A Golf Obsession Spanning Generations

Autor John Garrityen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2010 – vârsta de la 18 ani

One man's "poignant and revealing" quest to uncover the roots of his family's obsession with golf-in Ireland, Scotland, and the American heartland.

In Ancestral Links, senior Sports Illustrated writer John Garrity takes readers on a fascinating golfing odyssey. First he returns to the majestic seaside Carne Golf Links in a remote corner of Ireland, from which his great-grandfather left for America. Next he visits Musselburgh, Scotland, where his maternal ancestors played golf before the first thirteen rules of the game were written there in 1774. And in Wisconsin's St. Croix River Valley, Garrity revisits the New Richmond Golf Club, where his father learned the ancient game. At every stop on his journey, Garrity reflects on the life and career of his beloved late older brother, Tom, a former tour player.

Part memoir, part travelogue, and all golf, Garrity's story of how the sport altered three small-town landscapes and forever changed one family is a captivating and unforgettable tour of the links.

In Ancestral Links, senior Sports Illustrated writer John Garrity takes readers on a fascinating golfing odyssey. First he returns to the majestic seaside Carne Golf Links in a remote corner of Ireland, from which his great-grandfather left for America. Next he visits Musselburgh, Scotland, where his maternal ancestors played golf before the first thirteen rules of the game were written there in 1774. And in Wisconsin's St. Croix River Valley, Garrity revisits the New Richmond Golf Club, where his father learned the ancient game. At every stop on his journey, Garrity reflects on the life and career of his beloved late older brother, Tom, a former tour player.

Part memoir, part travelogue, and all golf, Garrity's story of how the sport altered three small-town landscapes and forever changed one family is a captivating and unforgettable tour of the links.

Preț: 136.30 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.08€ • 28.42$ • 21.98£

26.08€ • 28.42$ • 21.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780451229076

ISBN-10: 045122907X

Pagini: 292

Dimensiuni: 150 x 232 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: New American Library

ISBN-10: 045122907X

Pagini: 292

Dimensiuni: 150 x 232 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: New American Library

Notă biografică

John Garrity, a Golf Writers Association of America award-winner, is a senior writer at Sports Illustrated and a regular contributor to Golf Magazine and Travel &Leisure Golf, among other publications. He’s authored over a dozen books. He lives in Kansas City.

Extras

You don't expect to meet your familiar on the 11th hole at Carne.

It's a stunning hole: a par 4 that plays from a pinnacle tee to a canyon fairway and back up again to a green above a cow pasture that runs down to the beach. Huge terraced dunes line the fairway on either side. If you spray your tee shot you can wind up making an alpine-style ascent to a vertiginous perch to hit your second. There is also an unusual hazard down the left side, about 220 yards out — a grassy crater in a pulpitlike protrusion above the canyon floor.

"Hold on!" I yelled, watching my drive hook around the biggest dune and disappear from sight.

"Don't know about that," Gary said. "Could be all right."

I looked for a signal from the golfers waiting below, where the rough tumbled into a gorge. They had interrupted their search for a lost ball to wave us through, but now they were as still as the grazing ruminants in the meadow beyond.

"If my ball had cleared the crater, they'd be ducking." I slipped the head cover onto my hybrid 2 and returned the club to my bag.

Once we had all hit our tee shots, the players ahead resumed their search in the heights. They were assembled in the grassy crater when we arrived on the scene. One of them, a dark-haired flatbelly, was stoically appraising his options. His ball was buried in thick green grass on the face of the crater — a lie that Tiger Woods might have been able to negotiate, but no one else. The fellow seemed to understand this, because he worked himself into the only stance available to him — left foot on the rim of the crater, left leg bent, right leg straight as a fence post, right shoulder dipped, left ear aimed at the sky. Wasting no time, he took a healthy hack and staggered backward. The ball sailed out in a spray of grass clippings and looped listlessly toward the little gulch, where another uncharitable lie probably awaited him.

"Good out," I said.

"At least I didn't hurt myself." He shouldered his bag with a smile and descended from the crater with careful steps.

It took another minute or two for Gary to find my ball, and I wasn't too thrilled when he did. It, too, was in the face of the crater, just a few feet to the right of the spot where the previous victim had left his mark. Following his example, I planted my left foot at the level of my belt and swung with gritted teeth. There was a muffled click at impact. My ball popped out of the crater and followed gravity down to the fairway.

It wasn't until we stepped onto the 12th tee that Terry Swinson said anything. "Did you visit with John Geraghty?" he asked.

"How's that?" I wasn't sure what he was referring to.

"The fellow you were talking to back there. Haven't you met?"

I laughed and shook my head. I had spoken to John Geraghty on the phone recently, having spotted his name near mine on the Belmullet Golf Club roster. He had invited me to his house for a visit as soon as would be mutually convenient. But all I knew about John was that he lived out on the Mullet and he was "a builder" — a description that covered half the adult males in Western Mayo.

"What are the odds," I asked, "that two guys with the same name, who don't know each other and live on opposite sides of the Atlantic, would each hit a golf ball to the same spot, at the same time, on the same day?"

Gary grinned as he teed up his ball. "If you're talking about that particular spot, I'd say the odds are pretty good."

A couple of nights later, I drove back down the Blacksod Road to Aughleam, which, like most of the hamlets on the peninsula, was little more than a cluster of roadside buildings and a few farmhouses served by a rib road. Following John Geraghty's directions, I turned right at the designated signpost and drove up into the hills toward the ocean. "Look for the house on the left with the lights," he had said on the phone. Sure enough, there was a modern house with a long, straight driveway and illuminated by a row of ornamental lamps, like an airport runway. I turned in and eased my way up the hedge-lined drive, wondering it if was the Mullet Peninsula's equivalent of Magnolia Lane.

John opened the front door as I was walking up and extended his hand in greeting. "We meet again." He welcomed me into an entry lit by a chandelier. A room to the right was dark, but I could see into a modern kitchen at the back of the house. John steered me into a tastefully decorated parlor. Elegant curtains framed the windows. A glass corner cabinet housed crystal. It was a room you would expect to find in a high-end hotel or inn.

The picture was completed when John's wife, Kathleen, entered the room. A beautiful brunette, she wore her hair in one of those stylish shag cuts you see on TV presenters. She had on a blue tank top with glittery trim, and from her toned figure I deduced that she either had a home gym or was a regular at the Broadhaven Bay Hotel's state-of-the-art leisure center. She sat next to her handsome, dark-haired husband, and I couldn't help thinking that, as a pair, they were glam enough to crack the cast of the British soap, Footballers' Wives.

"It's a lovely house," I ventured. "Did you build it yourself?"

"No, no," John said. "I met Kathleen and we moved here in 2001."

"We just got married this year," she volunteered. She slipped off her shoes and drew her legs up under her. "No going back now, I guess." They laughed together.

I asked John about his golf game, and he shrugged. "It's been a quiet year for me, golfwise. We've been finishing up the place on the island."

"The island?"

"Inishkea South." John explained that he had a 5.5-meter RIB, which stood for Rigid Inflatable Boat. It was one of those Zodiac-style outboards that I'd seen on Broadhaven Bay. "We launch it in Blacksod Bay and go out to the islands."

"John is a sea fanatic," Kathleen said, "like he's a golf fanatic."

"We stay on the island on weekends," John said. "If you stand on the 14th tee box, you can look out and see us." He looked at his wife. "I don't know which is more peaceful, being on the island or being on the golf course."

I asked for a quick summary of his life in golf, and he readily complied. "I played soccer and Gaelic games," he said, "but the time came when I couldn't. So I took up golf. I used to play with the hurling grip, as we call it, the unorthodox grip." He butted his fists together with no overlapping or interlocking fingers. "I tried to change. I'd go to the local driving range and hit balls with a conventional grip, and the next day I'd have a pain in the shoulder."

"There's a driving range here?"

"No, in Blackrock, north of Dublin. That's where I was living at the time. But six years ago I went to a professional, and he taught me from scratch. I didn't see a golf course for three months." He pointed a thumb back over his shoulder. "I went up to a hill back here where Terry Swinson goes to hit golf balls. It's a big open area, all sand banks, and the grass is short because the animals keep it down. You'd think you were at Carne. Well, I hit balls there for three whole months until I got confident enough to take it to the course." While making the grip change, he added with a rueful shake of his head, his handicap had soared to 24. "But now it's back to 18."

"Which isn't bad at Carne," I said. I was thinking of my own 14.5.

He nodded. "The country members say an 18 handicapper at Carne will play to a 14 at any other course in the country, particularly a parkland course. Because Carne is so tough."

Kathleen went to get me a glass of water, and when she came back I had my notebook out. Following up on the Dublin reference, I asked if they were both born and raised on the Mullet. "I'm originally from here," she said. "I'm a Keane." She pronounced it Kane. "My family still has a little farm."

"A working farm?"

"Yes. It's nice to keep some traditions going." Her comment gave me the impression that farming on the Mullet was more of a hobby than a living.

"A lot of people who were brought up on the land have gone into building," John explained, "but I'm afraid our economic bubble will soon burst. A lot of those people will come back to work the land." As for his own background, John said he was from the seaside village of Blackrock, County Louth. "But my father was born just up the road here at Barrack."

"Big family?"

He nodded. "Nine in the family, five boys and four girls. My dad did his time in England, worked on the farms and then went to work for a construction firm. Fourteen years he was there, and then he married my mother. They returned to Ireland in '71, the year I was born. They wanted to bring the children up at home, but not all the way to Mayo, because they were afraid we wouldn't finish school here."V I nodded. I remembered my first trip here, in '89, when a Geraghty at Cross Lake had told me that Mullet emigrants rarely came back, "and why would they? They would want their children to be schooled." Education reforms, everybody now told me, had reversed that dismal trend. The Republic's system of public education was now the envy of most developed countries.

"I'm sorry. Your father's name is..." I looked up.

"John Geraghty, Sr. But they call him Jack."

I smiled over my notebook. "That was my dad's name."

"Really?" He didn't look that surprised. The Geraghtys had been recycling about a dozen male names since the time of the famine.

"I grew up in Blackrock," he continued, "but every summer and bank holiday we'd be up here at the family home at Barrack. Then my brother bought a holiday home here in 1999, and I renovated it. Which was my start in the building trade, although I picked up most of what I know from my father." More recently, John said, he and Kathleen had restored an old house on Inishkea South. Jack Geraghty loved the place and made any excuse to visit. "But he's unwell, he recently had a heart bypass. He's only gone 70, but..." John didn't finish the thought. "He still works in his workshop."

I waited for John to go on.

"My dad has tremendous stories," he said. "Like when they used to go to the dances. They'd cycle five miles to a dance in Blacksod, and after the dance they'd cycle back. And if it was a moonlit night they'd go down to the shore to see what had washed up."

"Beachcombing?" I had heard talk of the practice.

"Combing, yes. Cargo would be stored on the decks of ships, and sometimes it would be swept away in bad weather. Or they'd cut it loose. Barrels of coffee. Rope for mending nets. Bales of rubber. Barrels of whiskey. Timber being transported on big ships that sank. Big poles."

"They'd use that for fences," Kathleen interjected.

"Anything you could use or sell. My dad remembers nights when the moon was so bright you could see quite clearly where you were going. His mother would make up a pot of tea in a glass bottle and wrap a sock around it. To keep it warm."

John was leaning forward now. I got the feeling that Jack Geraghty was talking directly to me through his son, the way my father, Jack Garrity, sometimes talked through me.

"If an item was too heavy to lift," John continued, "they'd try to drag it above the high water mark. Then they'd put a stone on it or tie a bit of rope around it. They'd go home to get a couple of hours sleep and come back in the morning with a donkey or a cart."

"Tell him about the soldiers," Kathleen said.

John nodded. "During World War II, dead soldiers washed ashore. They brought them in and buried them." I was sure there was more to this story, but John didn't elaborate.

"Did combing die out with your dad's generation?"

"No!" He perked up. "There's stuff that can go in the best houses. Terry has a gorgeous teakwood fireplace in the back of his house. He found a teak stump on the beach and turned it into something beautiful."

I made a mental note to ask Terry about his find.

"We went on the shore tonight," Kathleen said, making me wonder if beachcombing had replaced golf and boating among upwardly mobile Mayoites. "We pick up the timbers and use them for firewood."

John smiled. "It's turned full circle. I'm doing what my dad did in the Fifties."

An hour later, on the road to Belmullet, I considered the chronology. John Geraghty's dad had been born in 1937, making him a contemporary not of my dad, but of my brother, who was also born in 1937. A split screen appeared in my mind's eye. On the one side I saw a 20-year-old Tommy Garrity tearing up the back nine in a match at the ritzy Kansas City Country Club. On the other I saw a 20-year-old Jack Geraghty stacking poles in the moonlight on the Mullet coast.

The images merged into John Geraghty — a modern-day Irishman who played golf at the Carne Golf Links and picked up driftwood on the sandy shore.

It's a stunning hole: a par 4 that plays from a pinnacle tee to a canyon fairway and back up again to a green above a cow pasture that runs down to the beach. Huge terraced dunes line the fairway on either side. If you spray your tee shot you can wind up making an alpine-style ascent to a vertiginous perch to hit your second. There is also an unusual hazard down the left side, about 220 yards out — a grassy crater in a pulpitlike protrusion above the canyon floor.

"Hold on!" I yelled, watching my drive hook around the biggest dune and disappear from sight.

"Don't know about that," Gary said. "Could be all right."

I looked for a signal from the golfers waiting below, where the rough tumbled into a gorge. They had interrupted their search for a lost ball to wave us through, but now they were as still as the grazing ruminants in the meadow beyond.

"If my ball had cleared the crater, they'd be ducking." I slipped the head cover onto my hybrid 2 and returned the club to my bag.

Once we had all hit our tee shots, the players ahead resumed their search in the heights. They were assembled in the grassy crater when we arrived on the scene. One of them, a dark-haired flatbelly, was stoically appraising his options. His ball was buried in thick green grass on the face of the crater — a lie that Tiger Woods might have been able to negotiate, but no one else. The fellow seemed to understand this, because he worked himself into the only stance available to him — left foot on the rim of the crater, left leg bent, right leg straight as a fence post, right shoulder dipped, left ear aimed at the sky. Wasting no time, he took a healthy hack and staggered backward. The ball sailed out in a spray of grass clippings and looped listlessly toward the little gulch, where another uncharitable lie probably awaited him.

"Good out," I said.

"At least I didn't hurt myself." He shouldered his bag with a smile and descended from the crater with careful steps.

It took another minute or two for Gary to find my ball, and I wasn't too thrilled when he did. It, too, was in the face of the crater, just a few feet to the right of the spot where the previous victim had left his mark. Following his example, I planted my left foot at the level of my belt and swung with gritted teeth. There was a muffled click at impact. My ball popped out of the crater and followed gravity down to the fairway.

It wasn't until we stepped onto the 12th tee that Terry Swinson said anything. "Did you visit with John Geraghty?" he asked.

"How's that?" I wasn't sure what he was referring to.

"The fellow you were talking to back there. Haven't you met?"

I laughed and shook my head. I had spoken to John Geraghty on the phone recently, having spotted his name near mine on the Belmullet Golf Club roster. He had invited me to his house for a visit as soon as would be mutually convenient. But all I knew about John was that he lived out on the Mullet and he was "a builder" — a description that covered half the adult males in Western Mayo.

"What are the odds," I asked, "that two guys with the same name, who don't know each other and live on opposite sides of the Atlantic, would each hit a golf ball to the same spot, at the same time, on the same day?"

Gary grinned as he teed up his ball. "If you're talking about that particular spot, I'd say the odds are pretty good."

A couple of nights later, I drove back down the Blacksod Road to Aughleam, which, like most of the hamlets on the peninsula, was little more than a cluster of roadside buildings and a few farmhouses served by a rib road. Following John Geraghty's directions, I turned right at the designated signpost and drove up into the hills toward the ocean. "Look for the house on the left with the lights," he had said on the phone. Sure enough, there was a modern house with a long, straight driveway and illuminated by a row of ornamental lamps, like an airport runway. I turned in and eased my way up the hedge-lined drive, wondering it if was the Mullet Peninsula's equivalent of Magnolia Lane.

John opened the front door as I was walking up and extended his hand in greeting. "We meet again." He welcomed me into an entry lit by a chandelier. A room to the right was dark, but I could see into a modern kitchen at the back of the house. John steered me into a tastefully decorated parlor. Elegant curtains framed the windows. A glass corner cabinet housed crystal. It was a room you would expect to find in a high-end hotel or inn.

The picture was completed when John's wife, Kathleen, entered the room. A beautiful brunette, she wore her hair in one of those stylish shag cuts you see on TV presenters. She had on a blue tank top with glittery trim, and from her toned figure I deduced that she either had a home gym or was a regular at the Broadhaven Bay Hotel's state-of-the-art leisure center. She sat next to her handsome, dark-haired husband, and I couldn't help thinking that, as a pair, they were glam enough to crack the cast of the British soap, Footballers' Wives.

"It's a lovely house," I ventured. "Did you build it yourself?"

"No, no," John said. "I met Kathleen and we moved here in 2001."

"We just got married this year," she volunteered. She slipped off her shoes and drew her legs up under her. "No going back now, I guess." They laughed together.

I asked John about his golf game, and he shrugged. "It's been a quiet year for me, golfwise. We've been finishing up the place on the island."

"The island?"

"Inishkea South." John explained that he had a 5.5-meter RIB, which stood for Rigid Inflatable Boat. It was one of those Zodiac-style outboards that I'd seen on Broadhaven Bay. "We launch it in Blacksod Bay and go out to the islands."

"John is a sea fanatic," Kathleen said, "like he's a golf fanatic."

"We stay on the island on weekends," John said. "If you stand on the 14th tee box, you can look out and see us." He looked at his wife. "I don't know which is more peaceful, being on the island or being on the golf course."

I asked for a quick summary of his life in golf, and he readily complied. "I played soccer and Gaelic games," he said, "but the time came when I couldn't. So I took up golf. I used to play with the hurling grip, as we call it, the unorthodox grip." He butted his fists together with no overlapping or interlocking fingers. "I tried to change. I'd go to the local driving range and hit balls with a conventional grip, and the next day I'd have a pain in the shoulder."

"There's a driving range here?"

"No, in Blackrock, north of Dublin. That's where I was living at the time. But six years ago I went to a professional, and he taught me from scratch. I didn't see a golf course for three months." He pointed a thumb back over his shoulder. "I went up to a hill back here where Terry Swinson goes to hit golf balls. It's a big open area, all sand banks, and the grass is short because the animals keep it down. You'd think you were at Carne. Well, I hit balls there for three whole months until I got confident enough to take it to the course." While making the grip change, he added with a rueful shake of his head, his handicap had soared to 24. "But now it's back to 18."

"Which isn't bad at Carne," I said. I was thinking of my own 14.5.

He nodded. "The country members say an 18 handicapper at Carne will play to a 14 at any other course in the country, particularly a parkland course. Because Carne is so tough."

Kathleen went to get me a glass of water, and when she came back I had my notebook out. Following up on the Dublin reference, I asked if they were both born and raised on the Mullet. "I'm originally from here," she said. "I'm a Keane." She pronounced it Kane. "My family still has a little farm."

"A working farm?"

"Yes. It's nice to keep some traditions going." Her comment gave me the impression that farming on the Mullet was more of a hobby than a living.

"A lot of people who were brought up on the land have gone into building," John explained, "but I'm afraid our economic bubble will soon burst. A lot of those people will come back to work the land." As for his own background, John said he was from the seaside village of Blackrock, County Louth. "But my father was born just up the road here at Barrack."

"Big family?"

He nodded. "Nine in the family, five boys and four girls. My dad did his time in England, worked on the farms and then went to work for a construction firm. Fourteen years he was there, and then he married my mother. They returned to Ireland in '71, the year I was born. They wanted to bring the children up at home, but not all the way to Mayo, because they were afraid we wouldn't finish school here."V I nodded. I remembered my first trip here, in '89, when a Geraghty at Cross Lake had told me that Mullet emigrants rarely came back, "and why would they? They would want their children to be schooled." Education reforms, everybody now told me, had reversed that dismal trend. The Republic's system of public education was now the envy of most developed countries.

"I'm sorry. Your father's name is..." I looked up.

"John Geraghty, Sr. But they call him Jack."

I smiled over my notebook. "That was my dad's name."

"Really?" He didn't look that surprised. The Geraghtys had been recycling about a dozen male names since the time of the famine.

"I grew up in Blackrock," he continued, "but every summer and bank holiday we'd be up here at the family home at Barrack. Then my brother bought a holiday home here in 1999, and I renovated it. Which was my start in the building trade, although I picked up most of what I know from my father." More recently, John said, he and Kathleen had restored an old house on Inishkea South. Jack Geraghty loved the place and made any excuse to visit. "But he's unwell, he recently had a heart bypass. He's only gone 70, but..." John didn't finish the thought. "He still works in his workshop."

I waited for John to go on.

"My dad has tremendous stories," he said. "Like when they used to go to the dances. They'd cycle five miles to a dance in Blacksod, and after the dance they'd cycle back. And if it was a moonlit night they'd go down to the shore to see what had washed up."

"Beachcombing?" I had heard talk of the practice.

"Combing, yes. Cargo would be stored on the decks of ships, and sometimes it would be swept away in bad weather. Or they'd cut it loose. Barrels of coffee. Rope for mending nets. Bales of rubber. Barrels of whiskey. Timber being transported on big ships that sank. Big poles."

"They'd use that for fences," Kathleen interjected.

"Anything you could use or sell. My dad remembers nights when the moon was so bright you could see quite clearly where you were going. His mother would make up a pot of tea in a glass bottle and wrap a sock around it. To keep it warm."

John was leaning forward now. I got the feeling that Jack Geraghty was talking directly to me through his son, the way my father, Jack Garrity, sometimes talked through me.

"If an item was too heavy to lift," John continued, "they'd try to drag it above the high water mark. Then they'd put a stone on it or tie a bit of rope around it. They'd go home to get a couple of hours sleep and come back in the morning with a donkey or a cart."

"Tell him about the soldiers," Kathleen said.

John nodded. "During World War II, dead soldiers washed ashore. They brought them in and buried them." I was sure there was more to this story, but John didn't elaborate.

"Did combing die out with your dad's generation?"

"No!" He perked up. "There's stuff that can go in the best houses. Terry has a gorgeous teakwood fireplace in the back of his house. He found a teak stump on the beach and turned it into something beautiful."

I made a mental note to ask Terry about his find.

"We went on the shore tonight," Kathleen said, making me wonder if beachcombing had replaced golf and boating among upwardly mobile Mayoites. "We pick up the timbers and use them for firewood."

John smiled. "It's turned full circle. I'm doing what my dad did in the Fifties."

An hour later, on the road to Belmullet, I considered the chronology. John Geraghty's dad had been born in 1937, making him a contemporary not of my dad, but of my brother, who was also born in 1937. A split screen appeared in my mind's eye. On the one side I saw a 20-year-old Tommy Garrity tearing up the back nine in a match at the ritzy Kansas City Country Club. On the other I saw a 20-year-old Jack Geraghty stacking poles in the moonlight on the Mullet coast.

The images merged into John Geraghty — a modern-day Irishman who played golf at the Carne Golf Links and picked up driftwood on the sandy shore.