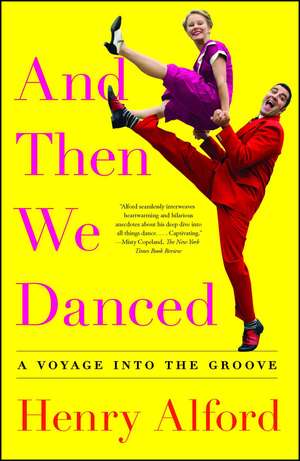

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

Autor Henry Alforden Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 iul 2019

When Henry Alford wrote about his experience with a Zumba class for The New York Times, little did he realize that it was the start of something much bigger. Dance would grow and take on many roles for Henry: exercise, stress reliever, confidence builder, an excuse to travel, a source of ongoing wonder, and—when he dances with Alzheimer’s patients—even a kind of community service.

Tackling a wide range of forms (including ballet, hip-hop, jazz, ballroom, tap, contact improvisation, Zumba, swing), Alford’s grand tour takes us through the works and careers of luminaries ranging from Bob Fosse to George Balanchine, Twyla Tharp to Arthur Murray. Rich in insight and humor, Alford mines both personal experience and fascinating cultural history to offer a witty and ultimately moving portrait of how dance can express all things human. And Then We Danced “is in one sense a celebration of hoofer in all its wonder and variety, from abandon to refinement. But it is also history, investigation, memoir, and even, in its smart, sly way, self-help…very funny, but more, it is joyful—a dance all its own” (Vanity Fair).

Preț: 90.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501122262

ISBN-10: 1501122266

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501122266

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Henry Alford has written for The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and The New York Times for two decades. His books include And Then We Danced, How to Live, and Big Kiss, which won a Thurber Prize for American humor.

Extras

And Then We Danced

THE INSTRUCTOR, AN ATTRACTIVE, WELL-DRESSED woman of a certain age named Jean Carden, looks out at a group of forty boys and girls aged nine to fourteen. We’re at the Gathering Place, a large, antiques-dappled catering hall in a sleepy town in North Carolina called Roxboro (pop. 8,632), and the kids are all dolled up: the boys are in blue blazers, neckties, and khakis, and the girls are in party dresses and white gloves. The young folks’ collective mood is a study in agitated boredom—imagine a DMV for people who still drink juice out of boxes.

In her honeyed Southern drawl, Carden asks the group, “Do you all recall how to sit pretty? Who’s going to sit pretty for me?”

An intrepid eleven-year-old boy raises his hand, and then, given the go-ahead by Carden, awkwardly motions to his partner to take her seat. As the boy lowers himself into the chair beside hers, he remembers to unbutton the top button of his jacket, as instructed.

Carden commends him warmly and then asks the group, “Now, who would like to demonstrate escort position?”

* * *

This is a cotillion, as offered by the National League of Junior Cotillions, an organization established in 1989 with the purpose of teaching young folk how “to act and learn to treat others with honor, dignity and respect for better relationships with family, friends and associates and to learn and practice ballroom dance.” There are now some three hundred cotillion chapters in over thirty states.

Of all the functions of dance that I’ll write about, Social Entrée (along with the possible inclusion of Religion) would seem at first blush to be the most rarefied. But that’s because, when people think of dance as a vehicle for social advancement, their brains alight first on fancy balls, an admittedly infrequent event in any mortal’s life. But once you factor in the cool points or prestige to be earned from going to nightclubs or certain other dances, or to any kind of concert dance, especially ballet, the map for advancement gets decidedly bigger.

The Social Entrée function is usually a form of connoisseurship. Typically, man’s dignity is linked to thought—the less practical the thought, the more esteem we give it—but who says that ornamental movement and gesture can’t occasionally yield respect, too? Moreover, as with poetry and opera, dance and its mysteries, not to mention its occasional extravagances, can elicit rolled eyeballs from the stoics and the uninitiated in the crowd—which, in a reverse-psychological way, can strengthen the resolve or exaltation of any individual hip enough to “get it.” Membership may, as the advertising world tells us, have its privileges; but rarefied membership has privileges and a vague sense of superiority or resolve.

The session of cotillion I’m watching is number two; after a third class, in a month’s time, the kids will attend a ball at a country club in Durham, some forty minutes away. During the ninety-minute class, Carden intersperses the five dances that she teaches—these include the waltz, the electric slide, and the shag—with manners drills. The drill that reoccurs the most—four times—is introducing yourself to others in the room. Carden repeatedly sings the praises of eye contact and a strong speaking voice.

Sometimes the vibe of Bygone Era in the room gives way to heavy irony, usually as prompted by the music played for each assigned activity. When doing a box-step waltz, for instance, many of the kids’ affect of grim penitence stands in dramatic contrast to a musical accompaniment the lyrics of which urge them twelve times to “let it go.” At another point Carden tells the kids to stand at one end of the room and then to approach her one at a time and introduce themselves. But when she cues the music, the hall fills not with the slinky samba or light processional music that you’d expect, but rather with a heartrending and poundingly operatic version of “Ave Maria.” It’s a synod with the Pope.

Toward the end of the session, Carden tells the boys to escort the girls to the refreshment table and to avail themselves of lemonade and cookies. Seldom do you see a level of concentration like the one displayed by a nine-year-old boy, under the watchful eyes of a chaperone, a dance instructor, and thirty-nine hungry colleagues, using delicate silver tongs to wrangle a large, floppy, soft-baked cookie. It feels like brain surgery for an audience of cannibals.

Then, once the kids are all seated and nibbling, Carden tells them about their homework. They are to practice rising from a chair five times; to introduce themselves to a new acquaintance; to introduce someone younger to someone older, and someone with an honorific to someone without one; and to give two compliments to family members and two to friends.

When the class is over, I chat up a group of kids, including a shy, ten-year-old boy who spends a lot of our conversation staring at the floor. I ask him if he had fun during the last ninety minutes of his life, and he robotically answers yes. Then I ask him if he thinks having taken cotillion classes for a year has helped him at all. He stares at the maple floorboards beneath us and says, “I like to know what to do when maybe I’m in a restaurant and there are five hundred forks.”

* * *

I hear ya, kid. My mother sent me to ballroom dancing classes when I was in the fifth grade. “It’s what you did then,” she told me recently, referencing the way a generalized feeling imparted by the media and acquaintances you meet in the produce section of your grocery store starts to simmer and simmer, finally bubbling over into an act of indeterminate purpose and questionable worth.

Previously, my mother had sent my three siblings to ballroom classes, too. When I asked my brother, Fred, what he thought had prompted her, he wrote me, “I think it was driven by her desire both to inoculate us with good manners and to establish or maintain social position amongst ‘the attractive people.’ Those urges must have been some mixture of insecurity, wanting to be admired by others, and a pre-digested sense of the proper order of the universe.”

The twining of dance and social advancement, of course, has a long history reaching back to the Renaissance, when dance manuals were full of tips about comportment and posture, as if to remind us that “illuminati” rhymes with “snotty.” Louis XIV’s great achievement in the history of ballet was in the 1660s to lead the idiom away from military arts like horse riding and fencing, where it had been couched, and to push it toward etiquette and decorum.

Because physical touch comes with an implicit set of guidelines and precautions, the successful deployment of same bespeaks sensitivity and self-restraint. As the motto of the dance academy where Ginger Rogers’s character works in Swing Time puts it, “To know how to dance is to know how to control oneself.” Or, as an etiquette guide popular in colonial America coached, “Put not thy hand in the presence of others to any part of thy body not ordinarily discovered.”

To this end, dancing, particularly ballroom and ballet, is often linked to the tropes of initiation and entrée—e.g., the first dance at weddings, or the first waltz at quinceañeras, wherein the father of the quinceañera dances with his daughter and then hands her off to her community. Once a dancer has been road-tested, she can be delivered to the new world she has chosen, thereupon to roar off into the night.

For professional dancers, the markers of social advancement are more aligned with quantities such as accreditation and celebrity. The flight path often runs: (1) Train till you bleed. (2) Join a company and distinguish yourself. (3) Write a memoir heavy on bonking. The prestige here is couched in steps 2 and 3, as the world marvels at what company you joined and what roles you danced. But there are lovely exceptions. In 1997 when the tap dancer Kaz Kumagai moved to New York from Sendai, Japan, at age nineteen, one of his early teachers, Derick K. Grant, was so impressed by Kumagai’s immersion into and respect for African-American culture—an understandably large part of the tap world—that Grant and other black dancers gave Kumagai the honorary “black” nickname Kenyon. Respect.

Regardless of whether you’re a social dancer or a professional one, all this weight can yield confusion and awkwardness. My ballroom classes took place in downtown Worcester, Massachusetts, in the basement of an imposing building that felt like the architectural equivalent of sclerosis. Once a week after school, twelve or so of us would gather and be indoctrinated in the rudimentary outlines of the fox-trot and the waltz. Chest up, shoulders down—how can you be upwardly mobile if you don’t have an erect spine?

I enjoyed spending time with my friends: two of the twelve were Carolyn and Dorothy, with whom I’d later do the Bus Stop. They lived in my neighborhood, and were among my closest friends. There was a lot of willed awkwardness about the dancing itself—if you made it look too easy or too fun, then you’d be curbing the amount of time you got to exploit the hallmarks of the adolescent experience, manufactured pain and squirming.

The lesson on offer didn’t seem to be about towing the line of being cool, or about dancing, but, rather, about interacting with members of the opposite sex. That a woman’s upper torso, save for her shoulders, was out of bounds was not news to me: I had two older sisters and thus knew that breasts and their environs were a no-go area. That sweaty hands were something to be avoided was a more novel idea to me, but certainly brushing my dewy palm against my hip before offering it to my dance partner was not difficult to master. I can wipe.

No, oddly, the biggest challenge of these lessons, it appeared to my then tender mind, had to do with table manners, or should I say, get-to-the-table manners. At these lessons, it turned out, dinner was served: a sturdy Crock-Pot full of gooey, fricasseed mystery awaited us at the end of each class. Each of us was to approach the food table, plop a big spoonful of rice and Crock-Potted goo onto our paper plate, and then tread very, very carefully the twenty or so feet to the dining table.

Not for us the sturdy reinforced cardboard that goes by the name Chinet. No, ours were the bendy, gossamer-thin paper plates which, if picked up by their edges, would immediately taco on you. Which same action caused a dribble of goop to cascade onto your bell-bottoms.

So my first true exposure to dance was, at heart, less kinesthetic than dry-cleanological.

* * *

Right around this same time in my life—this is the early 1970s—I’d had my first exposure to modern dance performed live. I was a second grader at the Bancroft School in Worcester, and at assembly one morning in the school’s auditorium, a woman danced for us. A zaftig, twenty-something gal in a tie-dyed leotard, she ambled out onto the stage and proceeded to thrash around to some percussive, conga-infused music, her body’s rolls of adipose tissue rippling and inadvertently bringing the neon blossoms of her bodysuit to life in the manner of a human lava lamp.

My schoolmates and I could not stop laughing. Why was she moving like that? I wondered. Why the tie-dyed leotard? At this point in my life, I’d become enamored of Carol Burnett and Lucille Ball, and I thought, Surely this pageant of flesh before my eyes is meant to be appreciated in the same light as Ms. Burnett and Ms. Ball’s work?

But, no. My homeroom teacher tapped me on the shoulder and looked at me crossly. Later that afternoon, our class was given a special admonitory lecture on art appreciation. We do not laugh at art, we were told. We admire it, we study it. We flat-line our gaping mouths and then cast over the remainder of our face a look of slightly dazed serenity. Later in our lives, we will resurrect this facial expression for run-ins with religious zealots, salespeople, art made from cat hair.

* * *

Whether you’re watching someone get jiggy with it, or you yourself are the jiggy-getter, you need to cultivate a sensitivity about the flesh on parade. This can be particularly acute for the jiggy-getters. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the most popular form of dancing, the minuet, took the idea that dance is a builder of character and ran with it. In having each couple dance alone with each other while all the other couples watched them, the minuet became a forum for judgment and tut-tutting that lacked only Dancing with the Stars–style score paddles: not only were the dancers currently in motion being silently judged on their technique, bearing, and posture, but, as Jack Anderson reminds us in Ballet & Modern Dance, their flaws in dancing were viewed as flaws in character, too. As Sarah, the duchess of Marlborough, said of one dancer who endured the gaze of the duchess’s gimlet eyes, “I think Sir S. Garth is the most honest and compassionate, but after the minuets which I have seen him dance . . . I can’t help thinking that he may sometimes be in the wrong.”

What’s interesting to me here is the grounds on which the dancer is being criticized: though the history of dance provides countless examples of people damning dance on the basis of wantonness and the ability of this particular branch of the arts to cause certain body parts to flap or rotate with an excessive vividness, the duchess and her criticism are decidedly bigger picture—she’s set her sights on honesty, compassion. We can almost see how, in the duchess’s eyes, Sir S. Garth is the type of dude who’ll step on a lot of toes, lie to the other dancers, and then ride home in his landau to not feed his kitten.

Other dancers, though, harness the moral gravitas they find in dance and use it to power a kind of sea change. Consider Jerome Robbins, who choreographed both for the ballet (Fancy Free, Afternoon of a Faun, Dances at a Gathering) and the theater (On the Town, Peter Pan, West Side Story). Robbins struggled for decades with his Judaism, at age thirteen chasing away schoolmates who peered into the Robbins family living room windows in Weehawken, New Jersey—they’d made faces while young Jerry Rabinowitz and a holy man from the local synagogue practiced reading the Torah. For the shame-filled young Robbins, ballet would have what he called a “civilizationizing” effect on his ancestral-tribal identity. “I affect a discipline over my body, and take on another language,” Robbins would write, “the language of court and Christianity—church and state—a completely artificial convention of movement—one that deforms and reforms the body and imposes a set of artificial conventions of beauty—a language not universal.”

* * *

One of the times that dance was a vehicle of entrée in my life, the idiom in question was neither ballroom nor ballet. In my junior year at the boarding school Hotchkiss, through the ministrations of a kindhearted high school pal, I was invited to the Gold and Silver Ball. Started in 1956, this New York City charity ball kicks off the winter breaks of teenage public and private schoolers in the Northeast, giving them an opportunity to swap stories about their parents’ divorce proceedings and to practice smuggling liquor into a non-stadium setting.

Back then the ball was held at the Plaza Hotel or the Waldorf Astoria, and featured the dulcet musical stylings of a society band like Lester Lanin’s, but in 1985 the ball moved downtown to the Ritz and later the Palladium, either because (according to the ball’s organizers) the Waldorf had become too expensive or because (according to high schoolers) a sofa had “slipped” out one of the Waldorf’s upstairs windows.

I remember how flattered I felt by the invitation. At my previous school, I’d been a storefront of overachievement, and, as a result, had had a series of nicknames leveled at me: Prez, Brain, Brownie, T.P. (for teacher’s pet), Toilet Paper. So when I got to Hotchkiss, I was anxious to be considered cool and not overly directed.

Also, at age sixteen, I was just starting to notice my attraction to men, but was embarrassed by same. My slightly desperate need to fit in lay at the heart of one of my more shameful acts from this period. A shy and soft-spoken guy who lived down the hall from me in my dorm—a social outlier, who was not in my clique—asked me one night if I wanted to get high. I said sure.

We followed the prescribed route for discreet pot-smoking: he’d rolled up one bath towel lengthwise and put it at the base of his door to prevent smoke from seeping into the hall, and he’d rolled one towel width-wise for us to exhale our hits into. He’d blasted the room with Ozium air sanitizer, and had put fresh water in his bong lest spilling stale water necessitate the ritualistic slaughter of an area rug.

But after we smoked up, he did something unexpected: he put his hand on my knee.

I immediately stood, mumbled thanks, and ran-walked to my room. My heart thudded like a stuffed animal being quickly dragged down a staircase; it seemed like the walls of the hallway engorged and contracted slightly with each hurried step I took.

Thereafter it took me three months to acknowledge this guy in public again, and sustained eye contact remained an impossibility for the rest of the year.

* * *

So, the invitation to the Gold and Silver. Given that many of Hotchkiss’s slightly intimidating coolios would be present at the ball, I thought, Why not? If I wanted to be cool myself, then I needed to log hours living amongst exemplars of that ethos; a burst of popularity, I thought, would smooth some of the tattered edges of my homophobia. The cost of the ball (more than $100) seemed exorbitant, and, moreover, I’d have to find a tuxedo somewhere, but: sure.

Back at my mom’s in Worcester over Thanksgiving break, I found an affordable tuxedo in a thrift shop. The jacket fit well, but the crotch of the pants sagged mid-distance between my knees and my fruit-and-veg. Only a haberdasher for dachshunds could imagine a world in which one’s genitals should fly so close to the sidewalk. I’ve never been noticeably well dressed—a WASPy wariness about caring too much about clothes runs in my family, and dovetailed nicely with my anxiety about appearing gay—but this was a new, uh, low. Once I’d brought my budget treasure back home, Mom laughingly pointed out that the waistband was a tad generous, too, so she nipped off an inch or so of it with her sewing machine. At last the pants made meaningful contact with my person.

Back at school, a month before the Gold and Silver, I had lots of time to feed my anxiety about mingling with my glittery friends while wearing pants that from certain angles still said “crotch goiter.” My classmates’ anxiety, meanwhile, was focused on where to drink before the ball—God forbid you should show up at the function not teetering on the brink of projectile vomiting. My high school memories are full of examples of trying to make the most of some tiny amount of some illegal substance; one Saturday we resorted to spiking a watermelon with half a bottle of dry vermouth. It’s a nice buzz, if you’re an ant.

Came the day of the ball. Let us summon up a cloud cover of empathy and indulgence over the next paragraph, as the author’s memories are, due to the ravages of alcohol and experiential fervor, somewhat impressionistic.

I don’t remember where I pre-gamed. I don’t remember where the ball was held. I do remember that the ball had a two-part construction: in one room, a society band played while girls in taffeta gowns and cocktail dresses touch-danced with their willing partners; in another room, rock boomed out of speakers. I gravitated, naturally, toward the latter.

The hours evanesced. No one mentioned my pants. I befriended no dachshunds.

But then, a few hours later that same night, something staggeringly, epically, supersonically groovy happened. Nine or so of us had ended up at our classmate Carl Sprague’s parents’ house for a nightcap. We were standing in the Spragues’ living room when someone informed me that we were all going to try to get into Studio 54. I laughed. My drunk had worn off by now, but, still: funny. We’d all heard about the illustrious nightclub—mostly stories about how impossible it was to get into. Each night a big crowd of people would mass in front of the velvet ropes in a pageant of ritual humiliation; over time, the people turned down by the bouncer would include Mick Jagger, Frank Sinatra, Warren Beatty, and Diane Keaton.

So my first reaction, on hearing the plan, was, Why bother? But then, given the jolliness of the evening, my second reaction was, What the hell?

I idly asked the group how many cabs we thought we’d need, and as my friends’ excited chirrups dissolved into more mundane mutterings related to coat retrieval and taxi logistics, I heard Carl say, “No, we don’t need cabs. I got a limo.”

That no one questioned or remarked upon this plot point—the surprise limo—says something about whimsical Carl, who had a bust of Byron in his dorm room and would grow up to be a production designer who’d work for Wes Anderson and Woody Allen.

Sure, I thought on hearing about the limo, we’ll be ignored or rejected by the bouncer, but the stretch will whisk us away in a glamorous storm cloud of slightly singed entitlement.

We piled into the vehicle.

After a drive across the gridded isle, the limo sidled up to the curb outside the club, where some sixty hopefuls were huddled on the sidewalk. As the nine of us tumbled out of the vehicle, I glanced at our group as if from the bouncer’s point of view: a knot of fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds in formal wear, their leader (Carl), six-foot-one and blond. We looked like the Norwegian cast of The Sound of Music.

Our bodies were somewhat smooshed together: it was cold, and we seemed to be unintentionally duplicating the crowded seating of the limo ride. The slick bottoms of my awful patent leather shoes were a slippery hell on the sidewalk; when I looked down, though, I noticed that no one else’s party shoes were faring much better.

Are you familiar with the Bob Fosse formation known as an amoeba? That’s when a very densely packed huddle of dancers moves cloud-like as one across the stage. Fosse got the idea from those people in Hieronymus Bosch paintings who are hatched from eggs and have multiple arms and legs.

Imagine a Fosse amoeba, but drunker, preppier.

The bouncer took one look at us, and waved us on in.

* * *

I’m intrigued that disco, a dance phenomenon originally promulgated in this country by minorities (blacks, Latins, gay men), partly in reaction to the dominance of rock and roll, would become so oppressively exclusive. Slightly antithetical, no? But I guess that when you build a shimmering island paradise out of body glitter and pairs of assless chaps, you can either say to the rest of the world “Come on in” or “You better be as decorative as we are.”

Studio 54 decidedly went with the latter, reordering the hierarchy by allowing admission only to those people fabulous enough not to be cowed by the club’s ninety-foot ceilings, its ceiling-suspended sculpture of a moon that snorted cocaine, the balcony bleachers covered with waterproof fabric that was hosed down daily. It was a bold clientele, a clientele unafraid to express itself via police whistle. (After President Carter’s mother, Lillian, went to Studio 54, she reported, “I’m not sure if it was heaven or hell. But it was wonderful.”) Outside on the sidewalk, co-owner Steve Rubell would stand on a fire hydrant to surveil the crowd of people trying to gain admission. “People would wait for hours in the freezing cold, knowing it was hopeless,” Johnny Morgan writes in Disco: The Music, the Times, the Era. “Sometimes someone would be allowed in if they took off their shirt, others if they stripped naked. [Doorman Marc Benecke] let in the male half of a honeymoon couple but not the wife. Limo drivers were let in, their hires not. Two girls arrived with a horse. Benecke had them strip naked, then said only the horse would be allowed in.” Donald Trump was a 54 regular, but would rarely dance; as one patron put it, Trump was there to cut the deal while others cut the coke.

For many of those admitted, the net effect of this stringent door policy was to make us fixate on the clubgoers. I managed to wiggle into Studio 54 three times over the years, and indeed, each time, people-watching was the draw. You might see the ectoplasmic Andy Warhol or the über-fabulous Grace Jones; you might see the transvestite roller skater in a wedding dress with the button that read “How Dare You Presume I’m Heterosexual”; you might see enough age-disparate male couples to suggest that the evening’s theme was Father-Son.

America.

Implicit to the trope of social entrée is the trope of personal transformation: by entering a new milieu, you are made new—or, at least, can choose to present yourself as someone new. According to the American Dream, life in our nation should be rich and fruity for all people regardless of their class or the circumstances of their birth. “Homeless to Harvard” is not just the name of a turgid movie on Lifetime, it’s a national ethos that bespeaks our dynamic, if sometimes crippling, fascination with destiny and self-transformation. Fueled by the popularity of Benjamin Franklin and his rags-to-riches trajectory, Americans have long clung to the belief that, with enough hard work, no one need ever learn that your birth name is James Gatz.

Which puts me in mind of a certain dance pioneer. Since the late 1950s, my family has been friends with Phyllis McDowell and her family, who lived about a mile away from us in New Haven, where we lived before we moved to Worcester. Phyllis McDowell is one of Arthur Murray’s twin daughters.

At mid-century, Arthur Murray’s name was synonymous with ballroom. A dance instructor turned entrepreneur, he had several hundred dance studios bearing his name, many of which still exist; it’s been estimated that over 5 million people have learned to dance because of these studios. His students over time would come to include Eleanor Roosevelt, John D. Rockefeller, the Duke of Windsor, Margaret Bourke-White, Enrico Caruso, Elizabeth Arden, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, and Jack Dempsey. In the movie Dirty Dancing, Patrick Swayze plays an Arthur Murray instructor.

Though I never met Mr. Murray or his wife, Murray’s name was invoked often in our household because of our friendship with the McDowells. My parents met Arthur and Kathryn Murray—“Once at the McDowells’ house. Phyllis and Teddy used to have us over to watch the show,” my mother told me, referring to The Arthur Murray Party, a dance show that ran from 1950 to 1960 and was hosted by Kathryn. “TV was pretty new then so you’d all get together to watch stuff.”

At the time, I was wholly uninterested in the fact that Phyllis and her four foxy daughters were the progeny of famous people. It simply didn’t compute. However, two facts about the McDowells made the clan fascinating to me: (1) their house had a bomb shelter, and (2) Mr. McDowell was rumored to have a knife inside his car in case he ever needed to cut himself out of his seat belt. This was a period of my life when I was devoting a lot of time thinking about rocket jet packs, so you can imagine the swank that a bomb shelter and a concealed weapon held for me; at some deep level of consciousness I must have realized that the McDowells were as close as I was ever going to get to the James Bond lifestyle.

Indeed, as if these two spectacularly cool items weren’t freighted enough with danger and excitement, there was yet a heightener: Phyllis’s twin sister, Jane, had married the man who invented the Heimlich maneuver. Yes, Mrs. Maneuver.

The level of emergency preparation in this family practically caused my young brain to explode; you imagined that if you bumped your head or skinned your knee at the McDowells’, chopper blades would signal the airborne arrival of cat-suited Coast Guard ninjas.

* * *

Born Moses Teichman in 1895 to poor, Jewish, Austrian-born parents who ran a bakery in New York City’s Harlem, Arthur Murray was, as he would later say, a “tall, gawky, and extremely shy” child. At Morris High School in the Bronx, he would add, “my bashfulness and diffidence had become pernicious habits.” He stuttered; his mother belittled her children and told them they’d never succeed.

Murray dropped out of school and struggled to keep various jobs, but after receiving dancing instruction from two sources—a female friend and a settlement house called the Education Alliance—he returned to school, which he now found easier because the dancing had given him a modicum of poise.

A serious student of architecture, Murray would find his fortune in the dancing craze of the 1910s (as the new century dawned, many Americans had grown tired of dancing to their grandparents’ music and had started dancing in huge numbers to ragtime instead). By day Murray worked in an architect’s office, and by night he frequented various New York City dance halls, where the raging popularity of animal dances like the turkey trot (dancers took four hopping steps sideways, with their feet apart) and the grizzly bear (dancers would stagger from side to side in emulation of a dancing bear, sometimes helpfully yelling, “It’s a bear!”) was slowly being supplanted by the calmer one-step (with their weight on their toes, dancers would travel across a room taking one step for each beat).

“Arthur first turned to social dancing as a means of meeting girls and becoming more popular,” his wife, Kathryn, would write in her book, My Husband, Arthur Murray, cowritten with Betty Hannah Hoffman. “To practice dancing, Arthur used to crash wedding receptions which were held in public halls.”

Murray left his architecture job and took classes with instructors Irene and Vernon Castle. The most famous dancers of their day, the Castles helped “tame” the wildness of the animal dances and made social dancing respectable. The Castles soon hired Murray to work at their school, Castle House. Then, after a sojourn teaching at a hotel in North Carolina for an instructor named the Baroness de Kuttleston, Murray opened the first Arthur Murray dance studio, located in the Georgian Terrace Hotel in Atlanta. By the time Murray stepped down from the presidency of his company in 1964, his three hundred franchised studios were grossing over $25 million a year.

* * *

What I love about Arthur Murray is his notion that dancing is a kind of conversation set to music. In his book How to Become a Good Dancer, he writes about how a foreigner who has not learned English has difficulty making himself understood. “He is so busy trying to think of the right words that he stammers and hesitates. And so it is with dancing. . . . To be a good dancer you must be able to dance without having to concentrate on the steps.”

The metaphor of dance-as-conversation also nods to the ever-escalating, back-and-forth nature of what is called a “challenge dance,” a feature of many dance idioms (e.g., tap dancing has the hoofer’s line, hip-hop has battles). In Top Hat, for instance, when Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance on the bandstand to “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?,” Fred does a step, Ginger copies it; Fred does another step, Ginger copies it but adds a little zing, etc.

But Murray’s story is equally interesting to me when seen in light of two themes that reoccur throughout the history of dance: humiliation and snobbery. Many dancers—Bob Fosse and Twyla Tharp among them—spend a part of their lives hiding from their friends and family and colleagues the fact that they dance. To admit that you’re a practitioner of the leaping arts is to open yourself to inspection on the fronts of economic status, carnality, taste, self-involvement, and body mass. For men, of course, the tendency to waft one’s person through space, be it for monetary gain or simply for enjoyment, is especially psychologically tender. Though typically the forces of antagonism here are bound up in notions of masculinity, sometimes they are more class-based: when in 1924 Kathryn introduced Arthur to her father on their first date, the father asked the young suitor what he did for a living. Murray chose not to mention that he had already put away $10,000 in the bank or that he drove a Rolls-Royce, but instead simply said that he danced. Kathryn’s father responded, “I do, too, but what do you do for a living?”

* * *

Whenever insecurity is much in evidence in a particular arena of activity—I’m looking at you, fashion, royal courts, glossy magazines, high-end restaurants—that arena’s denizens will, in an effort to ease anxiety, create or pay heed to easily recognizable protocols and brand names; e.g., your friend didn’t just spend $900 on shoes, she spent $900 on Manolo Blahniks. Murray’s uncanny talent as a salesman saw him both combating and employing this humiliation/snobbery axis. On the former front, he had great success selling mail-order dance instruction: customers could buy paper “footprints” that you’d put on the floor and step on. The footprints had markings that corresponded to directions in a booklet. His book How to Become a Good Dancer had you trace your own shoes onto paper, and then make five copies of your “feet.” Murray encouraged you to dance alone at first, until you got up and running. Imagine the relief that a pathologically shy, aspiring dancer would feel, knowing that he wouldn’t have to go to a studio and endure the gaze of others.

More tellingly yet, Murray the advertiser was not above speaking to a potential customer’s insecurities. “Most people lack confidence,” he told his wife. “Subconsciously, they would like to have more friends and be more popular, but they don’t openly recognize this desire.” When writing ad copy for his dance studios, Murray and his wife—one waggish line of criticism against Murray runs that, since Kathryn did most of the writing, Murray made his fortune “by the sweat of his frau”—sometimes mined Murray’s own travails from adolescence. An awkward evening he’d spent as a sixteen-year-old turned into an ad titled “How I Became Popular Overnight.” The ad’s copy ran, “Girls used to avoid me when I asked for a dance. Even the poorest dancers preferred to sit against the wall rather than dance with me. But I didn’t wake up until a partner left me alone standing in the middle of the floor. . . . As a social success I was a first-class failure.”

As Mrs. Murray writes in her book, “Arthur found that no man wanted to admit that he was learning to dance, but he didn’t mind saying that he was learning the rumba. It was something like the difference between saying your feet hurt and your foot hurts. We ran smart-looking ads that now sound corny, but they appealed in those days to businessmen who read New York’s leading newspapers and business journals: ‘Does your dancing say “New York” or “small town”? Where do the fastidious satisfy their craving for the up-to-the-minute dance steps and instruction? A secret? On the contrary, they happily pass the word about Arthur Murray’s delightfully modern studios where chic meet chic.’?” This ad was rigged out with pictures of attractive women; the pictures’ captions extolled these women’s good social backgrounds.

In its heyday, ballroom and its attendant glamour could take you places. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers both came from modest backgrounds, but went on to become icons of sophistication and elegance; ditto Astaire’s idols, Vernon and Irene Castle. In Murray’s case, ballroom’s power to raise one’s station in life was noticeable not only in who Murray became in his success but also in who worked for him. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, the fall of the Hapsburgs, and the upheavals of the Depression, impoverished European aristocrats were happy to take jobs as instructors at Arthur Murray studios: at one point Murray’s work staff included a baroness, several countesses, and a White Russian prince.

Pinkies: they’re for extending.

* * *

It occurred to me that I had a good opportunity to witness up close the aftermath of Murray’s work and life: I could talk to his daughter Phyllis McDowell. So, one balmy August day, I visited her at her summer house in Fenwick, an old-money enclave on the Connecticut shore where she’s been going for more than fifty years.

Phyllis, now eighty-nine, was all accommodation and bemusement and warmth. Barefoot, nut brown from tanning, and wearing a bright yellow Izod shirt and a Lilly Pulitzer skirt that set off her beautiful legs (she danced weekly until a few years ago), she invited me to sit on her porch and drink ice water with slices of lemon in it. Her silvery-white hair was held in place by a barrette. She has a sly smile and wonderfully warm, welcoming eyes that seem perpetually to be responding to faint music from another room.

I asked about the bomb shelter. (“Ted had some funny ideas,” she told me.) I asked about the footprints. (“It was a very architectural approach to dancing. If men were ever embarrassed about dancing, this mechanical approach made it much more palatable.”)

But what I really wondered was, What was it like to be the daughter of someone whose orientation—both to dance, and to life—was so aspirational? Phyllis told me, “Nothing escaped my father’s attention—like if the lightbulbs were dirty or there was dust anywhere. He was very fussy about grammar. He was intolerant of any indulgences—especially alcohol, which was my mother’s nemesis. He’d make you unpack a suitcase if you packed too much. No wonder I’m a Quaker now.”

Arthur and Kathryn Murray didn’t tell young Phyllis and Jane that the family was Jewish; when, as a teenager, Jane read about the traditional Jewish meal the seder, she thought it was a kind of wood. At age sixteen, Phyllis and Jane were taken to a plastic surgeon for nose jobs. The twin girls started attending Vassar, but when their father visited the campus one day he found the student body to be unkempt, so he convinced the girls to transfer to Sarah Lawrence.

In Phyllis and her sister’s youth, an instructor would come to their house each week to give them dance lessons (like her father, young Phyllis stuttered). After college, the two sisters spent a summer working as Arthur Murray instructors, during which time Phyllis fell in love with and married a fellow instructor, Mr. McDowell.

“Have you come across the story,” Phyllis asked me, chuckling, “where my father tells my mother, ‘We’re going to have a TV show! I want you to host it,’ and my mother says, ‘I don’t know anything about acting or singing,’ and my father tells her, ‘Don’t worry. The screens are so small that nobody will notice’?”

“I did see that,” I said. “I also liked in your mom’s book when she talked about doing acrobatics on the show in her ball gown, or roller-skating on the show, all of which caused you to ask her, ‘Mother, do you think the things you do are really appropriate?’?”

“We were such little snobs. Parents can’t do anything right. Here my parents were, adventurous enough to have their own TV show at a time when no one else except Milton Berle did. They were fun and funny. Mother would call me after every show from Sardi’s. It was exciting.”

As the afternoon wore on, Phyllis’s and my conversation gradually drifted toward her father’s demise in 1991. He and Kathryn were living in Honolulu at the time. Phyllis told me, “I remember just before he passed, he was lying out on the lanai. The last words I remember him saying were ‘We were so poor, we had to use newspaper as toilet paper.’ Isn’t that a peculiar thing to say? Why would you dwell on that?”

I tried, “Maybe it was a statement of appreciation? Like, life was so bad back in the day, but then he managed to make it a whole lot better?”

“That’s a nice way to look at it.”

I looked over Phyllis’s shoulder at the sparkly Connecticut Sound, only a block away. I had about an hour before my train back to New York, and Phyllis said she was going to lie down for a few minutes before driving me to the station. I said that I’d brought my bathing suit and was hoping to take a quick swim.

Phyllis, whose spirits had started visibly to flag, suddenly brightened. “That’s a great idea,” she said. “Take our golf cart!”

DANCE AS SOCIAL ENTRÉE

1.

THE INSTRUCTOR, AN ATTRACTIVE, WELL-DRESSED woman of a certain age named Jean Carden, looks out at a group of forty boys and girls aged nine to fourteen. We’re at the Gathering Place, a large, antiques-dappled catering hall in a sleepy town in North Carolina called Roxboro (pop. 8,632), and the kids are all dolled up: the boys are in blue blazers, neckties, and khakis, and the girls are in party dresses and white gloves. The young folks’ collective mood is a study in agitated boredom—imagine a DMV for people who still drink juice out of boxes.

In her honeyed Southern drawl, Carden asks the group, “Do you all recall how to sit pretty? Who’s going to sit pretty for me?”

An intrepid eleven-year-old boy raises his hand, and then, given the go-ahead by Carden, awkwardly motions to his partner to take her seat. As the boy lowers himself into the chair beside hers, he remembers to unbutton the top button of his jacket, as instructed.

Carden commends him warmly and then asks the group, “Now, who would like to demonstrate escort position?”

* * *

This is a cotillion, as offered by the National League of Junior Cotillions, an organization established in 1989 with the purpose of teaching young folk how “to act and learn to treat others with honor, dignity and respect for better relationships with family, friends and associates and to learn and practice ballroom dance.” There are now some three hundred cotillion chapters in over thirty states.

Of all the functions of dance that I’ll write about, Social Entrée (along with the possible inclusion of Religion) would seem at first blush to be the most rarefied. But that’s because, when people think of dance as a vehicle for social advancement, their brains alight first on fancy balls, an admittedly infrequent event in any mortal’s life. But once you factor in the cool points or prestige to be earned from going to nightclubs or certain other dances, or to any kind of concert dance, especially ballet, the map for advancement gets decidedly bigger.

The Social Entrée function is usually a form of connoisseurship. Typically, man’s dignity is linked to thought—the less practical the thought, the more esteem we give it—but who says that ornamental movement and gesture can’t occasionally yield respect, too? Moreover, as with poetry and opera, dance and its mysteries, not to mention its occasional extravagances, can elicit rolled eyeballs from the stoics and the uninitiated in the crowd—which, in a reverse-psychological way, can strengthen the resolve or exaltation of any individual hip enough to “get it.” Membership may, as the advertising world tells us, have its privileges; but rarefied membership has privileges and a vague sense of superiority or resolve.

The session of cotillion I’m watching is number two; after a third class, in a month’s time, the kids will attend a ball at a country club in Durham, some forty minutes away. During the ninety-minute class, Carden intersperses the five dances that she teaches—these include the waltz, the electric slide, and the shag—with manners drills. The drill that reoccurs the most—four times—is introducing yourself to others in the room. Carden repeatedly sings the praises of eye contact and a strong speaking voice.

Sometimes the vibe of Bygone Era in the room gives way to heavy irony, usually as prompted by the music played for each assigned activity. When doing a box-step waltz, for instance, many of the kids’ affect of grim penitence stands in dramatic contrast to a musical accompaniment the lyrics of which urge them twelve times to “let it go.” At another point Carden tells the kids to stand at one end of the room and then to approach her one at a time and introduce themselves. But when she cues the music, the hall fills not with the slinky samba or light processional music that you’d expect, but rather with a heartrending and poundingly operatic version of “Ave Maria.” It’s a synod with the Pope.

Toward the end of the session, Carden tells the boys to escort the girls to the refreshment table and to avail themselves of lemonade and cookies. Seldom do you see a level of concentration like the one displayed by a nine-year-old boy, under the watchful eyes of a chaperone, a dance instructor, and thirty-nine hungry colleagues, using delicate silver tongs to wrangle a large, floppy, soft-baked cookie. It feels like brain surgery for an audience of cannibals.

Then, once the kids are all seated and nibbling, Carden tells them about their homework. They are to practice rising from a chair five times; to introduce themselves to a new acquaintance; to introduce someone younger to someone older, and someone with an honorific to someone without one; and to give two compliments to family members and two to friends.

When the class is over, I chat up a group of kids, including a shy, ten-year-old boy who spends a lot of our conversation staring at the floor. I ask him if he had fun during the last ninety minutes of his life, and he robotically answers yes. Then I ask him if he thinks having taken cotillion classes for a year has helped him at all. He stares at the maple floorboards beneath us and says, “I like to know what to do when maybe I’m in a restaurant and there are five hundred forks.”

* * *

I hear ya, kid. My mother sent me to ballroom dancing classes when I was in the fifth grade. “It’s what you did then,” she told me recently, referencing the way a generalized feeling imparted by the media and acquaintances you meet in the produce section of your grocery store starts to simmer and simmer, finally bubbling over into an act of indeterminate purpose and questionable worth.

Previously, my mother had sent my three siblings to ballroom classes, too. When I asked my brother, Fred, what he thought had prompted her, he wrote me, “I think it was driven by her desire both to inoculate us with good manners and to establish or maintain social position amongst ‘the attractive people.’ Those urges must have been some mixture of insecurity, wanting to be admired by others, and a pre-digested sense of the proper order of the universe.”

The twining of dance and social advancement, of course, has a long history reaching back to the Renaissance, when dance manuals were full of tips about comportment and posture, as if to remind us that “illuminati” rhymes with “snotty.” Louis XIV’s great achievement in the history of ballet was in the 1660s to lead the idiom away from military arts like horse riding and fencing, where it had been couched, and to push it toward etiquette and decorum.

Because physical touch comes with an implicit set of guidelines and precautions, the successful deployment of same bespeaks sensitivity and self-restraint. As the motto of the dance academy where Ginger Rogers’s character works in Swing Time puts it, “To know how to dance is to know how to control oneself.” Or, as an etiquette guide popular in colonial America coached, “Put not thy hand in the presence of others to any part of thy body not ordinarily discovered.”

To this end, dancing, particularly ballroom and ballet, is often linked to the tropes of initiation and entrée—e.g., the first dance at weddings, or the first waltz at quinceañeras, wherein the father of the quinceañera dances with his daughter and then hands her off to her community. Once a dancer has been road-tested, she can be delivered to the new world she has chosen, thereupon to roar off into the night.

For professional dancers, the markers of social advancement are more aligned with quantities such as accreditation and celebrity. The flight path often runs: (1) Train till you bleed. (2) Join a company and distinguish yourself. (3) Write a memoir heavy on bonking. The prestige here is couched in steps 2 and 3, as the world marvels at what company you joined and what roles you danced. But there are lovely exceptions. In 1997 when the tap dancer Kaz Kumagai moved to New York from Sendai, Japan, at age nineteen, one of his early teachers, Derick K. Grant, was so impressed by Kumagai’s immersion into and respect for African-American culture—an understandably large part of the tap world—that Grant and other black dancers gave Kumagai the honorary “black” nickname Kenyon. Respect.

Regardless of whether you’re a social dancer or a professional one, all this weight can yield confusion and awkwardness. My ballroom classes took place in downtown Worcester, Massachusetts, in the basement of an imposing building that felt like the architectural equivalent of sclerosis. Once a week after school, twelve or so of us would gather and be indoctrinated in the rudimentary outlines of the fox-trot and the waltz. Chest up, shoulders down—how can you be upwardly mobile if you don’t have an erect spine?

I enjoyed spending time with my friends: two of the twelve were Carolyn and Dorothy, with whom I’d later do the Bus Stop. They lived in my neighborhood, and were among my closest friends. There was a lot of willed awkwardness about the dancing itself—if you made it look too easy or too fun, then you’d be curbing the amount of time you got to exploit the hallmarks of the adolescent experience, manufactured pain and squirming.

The lesson on offer didn’t seem to be about towing the line of being cool, or about dancing, but, rather, about interacting with members of the opposite sex. That a woman’s upper torso, save for her shoulders, was out of bounds was not news to me: I had two older sisters and thus knew that breasts and their environs were a no-go area. That sweaty hands were something to be avoided was a more novel idea to me, but certainly brushing my dewy palm against my hip before offering it to my dance partner was not difficult to master. I can wipe.

No, oddly, the biggest challenge of these lessons, it appeared to my then tender mind, had to do with table manners, or should I say, get-to-the-table manners. At these lessons, it turned out, dinner was served: a sturdy Crock-Pot full of gooey, fricasseed mystery awaited us at the end of each class. Each of us was to approach the food table, plop a big spoonful of rice and Crock-Potted goo onto our paper plate, and then tread very, very carefully the twenty or so feet to the dining table.

Not for us the sturdy reinforced cardboard that goes by the name Chinet. No, ours were the bendy, gossamer-thin paper plates which, if picked up by their edges, would immediately taco on you. Which same action caused a dribble of goop to cascade onto your bell-bottoms.

So my first true exposure to dance was, at heart, less kinesthetic than dry-cleanological.

* * *

Right around this same time in my life—this is the early 1970s—I’d had my first exposure to modern dance performed live. I was a second grader at the Bancroft School in Worcester, and at assembly one morning in the school’s auditorium, a woman danced for us. A zaftig, twenty-something gal in a tie-dyed leotard, she ambled out onto the stage and proceeded to thrash around to some percussive, conga-infused music, her body’s rolls of adipose tissue rippling and inadvertently bringing the neon blossoms of her bodysuit to life in the manner of a human lava lamp.

My schoolmates and I could not stop laughing. Why was she moving like that? I wondered. Why the tie-dyed leotard? At this point in my life, I’d become enamored of Carol Burnett and Lucille Ball, and I thought, Surely this pageant of flesh before my eyes is meant to be appreciated in the same light as Ms. Burnett and Ms. Ball’s work?

But, no. My homeroom teacher tapped me on the shoulder and looked at me crossly. Later that afternoon, our class was given a special admonitory lecture on art appreciation. We do not laugh at art, we were told. We admire it, we study it. We flat-line our gaping mouths and then cast over the remainder of our face a look of slightly dazed serenity. Later in our lives, we will resurrect this facial expression for run-ins with religious zealots, salespeople, art made from cat hair.

* * *

Whether you’re watching someone get jiggy with it, or you yourself are the jiggy-getter, you need to cultivate a sensitivity about the flesh on parade. This can be particularly acute for the jiggy-getters. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the most popular form of dancing, the minuet, took the idea that dance is a builder of character and ran with it. In having each couple dance alone with each other while all the other couples watched them, the minuet became a forum for judgment and tut-tutting that lacked only Dancing with the Stars–style score paddles: not only were the dancers currently in motion being silently judged on their technique, bearing, and posture, but, as Jack Anderson reminds us in Ballet & Modern Dance, their flaws in dancing were viewed as flaws in character, too. As Sarah, the duchess of Marlborough, said of one dancer who endured the gaze of the duchess’s gimlet eyes, “I think Sir S. Garth is the most honest and compassionate, but after the minuets which I have seen him dance . . . I can’t help thinking that he may sometimes be in the wrong.”

What’s interesting to me here is the grounds on which the dancer is being criticized: though the history of dance provides countless examples of people damning dance on the basis of wantonness and the ability of this particular branch of the arts to cause certain body parts to flap or rotate with an excessive vividness, the duchess and her criticism are decidedly bigger picture—she’s set her sights on honesty, compassion. We can almost see how, in the duchess’s eyes, Sir S. Garth is the type of dude who’ll step on a lot of toes, lie to the other dancers, and then ride home in his landau to not feed his kitten.

Other dancers, though, harness the moral gravitas they find in dance and use it to power a kind of sea change. Consider Jerome Robbins, who choreographed both for the ballet (Fancy Free, Afternoon of a Faun, Dances at a Gathering) and the theater (On the Town, Peter Pan, West Side Story). Robbins struggled for decades with his Judaism, at age thirteen chasing away schoolmates who peered into the Robbins family living room windows in Weehawken, New Jersey—they’d made faces while young Jerry Rabinowitz and a holy man from the local synagogue practiced reading the Torah. For the shame-filled young Robbins, ballet would have what he called a “civilizationizing” effect on his ancestral-tribal identity. “I affect a discipline over my body, and take on another language,” Robbins would write, “the language of court and Christianity—church and state—a completely artificial convention of movement—one that deforms and reforms the body and imposes a set of artificial conventions of beauty—a language not universal.”

* * *

One of the times that dance was a vehicle of entrée in my life, the idiom in question was neither ballroom nor ballet. In my junior year at the boarding school Hotchkiss, through the ministrations of a kindhearted high school pal, I was invited to the Gold and Silver Ball. Started in 1956, this New York City charity ball kicks off the winter breaks of teenage public and private schoolers in the Northeast, giving them an opportunity to swap stories about their parents’ divorce proceedings and to practice smuggling liquor into a non-stadium setting.

Back then the ball was held at the Plaza Hotel or the Waldorf Astoria, and featured the dulcet musical stylings of a society band like Lester Lanin’s, but in 1985 the ball moved downtown to the Ritz and later the Palladium, either because (according to the ball’s organizers) the Waldorf had become too expensive or because (according to high schoolers) a sofa had “slipped” out one of the Waldorf’s upstairs windows.

I remember how flattered I felt by the invitation. At my previous school, I’d been a storefront of overachievement, and, as a result, had had a series of nicknames leveled at me: Prez, Brain, Brownie, T.P. (for teacher’s pet), Toilet Paper. So when I got to Hotchkiss, I was anxious to be considered cool and not overly directed.

Also, at age sixteen, I was just starting to notice my attraction to men, but was embarrassed by same. My slightly desperate need to fit in lay at the heart of one of my more shameful acts from this period. A shy and soft-spoken guy who lived down the hall from me in my dorm—a social outlier, who was not in my clique—asked me one night if I wanted to get high. I said sure.

We followed the prescribed route for discreet pot-smoking: he’d rolled up one bath towel lengthwise and put it at the base of his door to prevent smoke from seeping into the hall, and he’d rolled one towel width-wise for us to exhale our hits into. He’d blasted the room with Ozium air sanitizer, and had put fresh water in his bong lest spilling stale water necessitate the ritualistic slaughter of an area rug.

But after we smoked up, he did something unexpected: he put his hand on my knee.

I immediately stood, mumbled thanks, and ran-walked to my room. My heart thudded like a stuffed animal being quickly dragged down a staircase; it seemed like the walls of the hallway engorged and contracted slightly with each hurried step I took.

Thereafter it took me three months to acknowledge this guy in public again, and sustained eye contact remained an impossibility for the rest of the year.

* * *

So, the invitation to the Gold and Silver. Given that many of Hotchkiss’s slightly intimidating coolios would be present at the ball, I thought, Why not? If I wanted to be cool myself, then I needed to log hours living amongst exemplars of that ethos; a burst of popularity, I thought, would smooth some of the tattered edges of my homophobia. The cost of the ball (more than $100) seemed exorbitant, and, moreover, I’d have to find a tuxedo somewhere, but: sure.

Back at my mom’s in Worcester over Thanksgiving break, I found an affordable tuxedo in a thrift shop. The jacket fit well, but the crotch of the pants sagged mid-distance between my knees and my fruit-and-veg. Only a haberdasher for dachshunds could imagine a world in which one’s genitals should fly so close to the sidewalk. I’ve never been noticeably well dressed—a WASPy wariness about caring too much about clothes runs in my family, and dovetailed nicely with my anxiety about appearing gay—but this was a new, uh, low. Once I’d brought my budget treasure back home, Mom laughingly pointed out that the waistband was a tad generous, too, so she nipped off an inch or so of it with her sewing machine. At last the pants made meaningful contact with my person.

Back at school, a month before the Gold and Silver, I had lots of time to feed my anxiety about mingling with my glittery friends while wearing pants that from certain angles still said “crotch goiter.” My classmates’ anxiety, meanwhile, was focused on where to drink before the ball—God forbid you should show up at the function not teetering on the brink of projectile vomiting. My high school memories are full of examples of trying to make the most of some tiny amount of some illegal substance; one Saturday we resorted to spiking a watermelon with half a bottle of dry vermouth. It’s a nice buzz, if you’re an ant.

Came the day of the ball. Let us summon up a cloud cover of empathy and indulgence over the next paragraph, as the author’s memories are, due to the ravages of alcohol and experiential fervor, somewhat impressionistic.

I don’t remember where I pre-gamed. I don’t remember where the ball was held. I do remember that the ball had a two-part construction: in one room, a society band played while girls in taffeta gowns and cocktail dresses touch-danced with their willing partners; in another room, rock boomed out of speakers. I gravitated, naturally, toward the latter.

The hours evanesced. No one mentioned my pants. I befriended no dachshunds.

But then, a few hours later that same night, something staggeringly, epically, supersonically groovy happened. Nine or so of us had ended up at our classmate Carl Sprague’s parents’ house for a nightcap. We were standing in the Spragues’ living room when someone informed me that we were all going to try to get into Studio 54. I laughed. My drunk had worn off by now, but, still: funny. We’d all heard about the illustrious nightclub—mostly stories about how impossible it was to get into. Each night a big crowd of people would mass in front of the velvet ropes in a pageant of ritual humiliation; over time, the people turned down by the bouncer would include Mick Jagger, Frank Sinatra, Warren Beatty, and Diane Keaton.

So my first reaction, on hearing the plan, was, Why bother? But then, given the jolliness of the evening, my second reaction was, What the hell?

I idly asked the group how many cabs we thought we’d need, and as my friends’ excited chirrups dissolved into more mundane mutterings related to coat retrieval and taxi logistics, I heard Carl say, “No, we don’t need cabs. I got a limo.”

That no one questioned or remarked upon this plot point—the surprise limo—says something about whimsical Carl, who had a bust of Byron in his dorm room and would grow up to be a production designer who’d work for Wes Anderson and Woody Allen.

Sure, I thought on hearing about the limo, we’ll be ignored or rejected by the bouncer, but the stretch will whisk us away in a glamorous storm cloud of slightly singed entitlement.

We piled into the vehicle.

After a drive across the gridded isle, the limo sidled up to the curb outside the club, where some sixty hopefuls were huddled on the sidewalk. As the nine of us tumbled out of the vehicle, I glanced at our group as if from the bouncer’s point of view: a knot of fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds in formal wear, their leader (Carl), six-foot-one and blond. We looked like the Norwegian cast of The Sound of Music.

Our bodies were somewhat smooshed together: it was cold, and we seemed to be unintentionally duplicating the crowded seating of the limo ride. The slick bottoms of my awful patent leather shoes were a slippery hell on the sidewalk; when I looked down, though, I noticed that no one else’s party shoes were faring much better.

Are you familiar with the Bob Fosse formation known as an amoeba? That’s when a very densely packed huddle of dancers moves cloud-like as one across the stage. Fosse got the idea from those people in Hieronymus Bosch paintings who are hatched from eggs and have multiple arms and legs.

Imagine a Fosse amoeba, but drunker, preppier.

The bouncer took one look at us, and waved us on in.

* * *

I’m intrigued that disco, a dance phenomenon originally promulgated in this country by minorities (blacks, Latins, gay men), partly in reaction to the dominance of rock and roll, would become so oppressively exclusive. Slightly antithetical, no? But I guess that when you build a shimmering island paradise out of body glitter and pairs of assless chaps, you can either say to the rest of the world “Come on in” or “You better be as decorative as we are.”

Studio 54 decidedly went with the latter, reordering the hierarchy by allowing admission only to those people fabulous enough not to be cowed by the club’s ninety-foot ceilings, its ceiling-suspended sculpture of a moon that snorted cocaine, the balcony bleachers covered with waterproof fabric that was hosed down daily. It was a bold clientele, a clientele unafraid to express itself via police whistle. (After President Carter’s mother, Lillian, went to Studio 54, she reported, “I’m not sure if it was heaven or hell. But it was wonderful.”) Outside on the sidewalk, co-owner Steve Rubell would stand on a fire hydrant to surveil the crowd of people trying to gain admission. “People would wait for hours in the freezing cold, knowing it was hopeless,” Johnny Morgan writes in Disco: The Music, the Times, the Era. “Sometimes someone would be allowed in if they took off their shirt, others if they stripped naked. [Doorman Marc Benecke] let in the male half of a honeymoon couple but not the wife. Limo drivers were let in, their hires not. Two girls arrived with a horse. Benecke had them strip naked, then said only the horse would be allowed in.” Donald Trump was a 54 regular, but would rarely dance; as one patron put it, Trump was there to cut the deal while others cut the coke.

For many of those admitted, the net effect of this stringent door policy was to make us fixate on the clubgoers. I managed to wiggle into Studio 54 three times over the years, and indeed, each time, people-watching was the draw. You might see the ectoplasmic Andy Warhol or the über-fabulous Grace Jones; you might see the transvestite roller skater in a wedding dress with the button that read “How Dare You Presume I’m Heterosexual”; you might see enough age-disparate male couples to suggest that the evening’s theme was Father-Son.

America.

2.

Implicit to the trope of social entrée is the trope of personal transformation: by entering a new milieu, you are made new—or, at least, can choose to present yourself as someone new. According to the American Dream, life in our nation should be rich and fruity for all people regardless of their class or the circumstances of their birth. “Homeless to Harvard” is not just the name of a turgid movie on Lifetime, it’s a national ethos that bespeaks our dynamic, if sometimes crippling, fascination with destiny and self-transformation. Fueled by the popularity of Benjamin Franklin and his rags-to-riches trajectory, Americans have long clung to the belief that, with enough hard work, no one need ever learn that your birth name is James Gatz.

Which puts me in mind of a certain dance pioneer. Since the late 1950s, my family has been friends with Phyllis McDowell and her family, who lived about a mile away from us in New Haven, where we lived before we moved to Worcester. Phyllis McDowell is one of Arthur Murray’s twin daughters.

At mid-century, Arthur Murray’s name was synonymous with ballroom. A dance instructor turned entrepreneur, he had several hundred dance studios bearing his name, many of which still exist; it’s been estimated that over 5 million people have learned to dance because of these studios. His students over time would come to include Eleanor Roosevelt, John D. Rockefeller, the Duke of Windsor, Margaret Bourke-White, Enrico Caruso, Elizabeth Arden, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, and Jack Dempsey. In the movie Dirty Dancing, Patrick Swayze plays an Arthur Murray instructor.

Though I never met Mr. Murray or his wife, Murray’s name was invoked often in our household because of our friendship with the McDowells. My parents met Arthur and Kathryn Murray—“Once at the McDowells’ house. Phyllis and Teddy used to have us over to watch the show,” my mother told me, referring to The Arthur Murray Party, a dance show that ran from 1950 to 1960 and was hosted by Kathryn. “TV was pretty new then so you’d all get together to watch stuff.”

At the time, I was wholly uninterested in the fact that Phyllis and her four foxy daughters were the progeny of famous people. It simply didn’t compute. However, two facts about the McDowells made the clan fascinating to me: (1) their house had a bomb shelter, and (2) Mr. McDowell was rumored to have a knife inside his car in case he ever needed to cut himself out of his seat belt. This was a period of my life when I was devoting a lot of time thinking about rocket jet packs, so you can imagine the swank that a bomb shelter and a concealed weapon held for me; at some deep level of consciousness I must have realized that the McDowells were as close as I was ever going to get to the James Bond lifestyle.

Indeed, as if these two spectacularly cool items weren’t freighted enough with danger and excitement, there was yet a heightener: Phyllis’s twin sister, Jane, had married the man who invented the Heimlich maneuver. Yes, Mrs. Maneuver.

The level of emergency preparation in this family practically caused my young brain to explode; you imagined that if you bumped your head or skinned your knee at the McDowells’, chopper blades would signal the airborne arrival of cat-suited Coast Guard ninjas.

* * *

Born Moses Teichman in 1895 to poor, Jewish, Austrian-born parents who ran a bakery in New York City’s Harlem, Arthur Murray was, as he would later say, a “tall, gawky, and extremely shy” child. At Morris High School in the Bronx, he would add, “my bashfulness and diffidence had become pernicious habits.” He stuttered; his mother belittled her children and told them they’d never succeed.

Murray dropped out of school and struggled to keep various jobs, but after receiving dancing instruction from two sources—a female friend and a settlement house called the Education Alliance—he returned to school, which he now found easier because the dancing had given him a modicum of poise.

A serious student of architecture, Murray would find his fortune in the dancing craze of the 1910s (as the new century dawned, many Americans had grown tired of dancing to their grandparents’ music and had started dancing in huge numbers to ragtime instead). By day Murray worked in an architect’s office, and by night he frequented various New York City dance halls, where the raging popularity of animal dances like the turkey trot (dancers took four hopping steps sideways, with their feet apart) and the grizzly bear (dancers would stagger from side to side in emulation of a dancing bear, sometimes helpfully yelling, “It’s a bear!”) was slowly being supplanted by the calmer one-step (with their weight on their toes, dancers would travel across a room taking one step for each beat).

“Arthur first turned to social dancing as a means of meeting girls and becoming more popular,” his wife, Kathryn, would write in her book, My Husband, Arthur Murray, cowritten with Betty Hannah Hoffman. “To practice dancing, Arthur used to crash wedding receptions which were held in public halls.”

Murray left his architecture job and took classes with instructors Irene and Vernon Castle. The most famous dancers of their day, the Castles helped “tame” the wildness of the animal dances and made social dancing respectable. The Castles soon hired Murray to work at their school, Castle House. Then, after a sojourn teaching at a hotel in North Carolina for an instructor named the Baroness de Kuttleston, Murray opened the first Arthur Murray dance studio, located in the Georgian Terrace Hotel in Atlanta. By the time Murray stepped down from the presidency of his company in 1964, his three hundred franchised studios were grossing over $25 million a year.

* * *

What I love about Arthur Murray is his notion that dancing is a kind of conversation set to music. In his book How to Become a Good Dancer, he writes about how a foreigner who has not learned English has difficulty making himself understood. “He is so busy trying to think of the right words that he stammers and hesitates. And so it is with dancing. . . . To be a good dancer you must be able to dance without having to concentrate on the steps.”

The metaphor of dance-as-conversation also nods to the ever-escalating, back-and-forth nature of what is called a “challenge dance,” a feature of many dance idioms (e.g., tap dancing has the hoofer’s line, hip-hop has battles). In Top Hat, for instance, when Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance on the bandstand to “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?,” Fred does a step, Ginger copies it; Fred does another step, Ginger copies it but adds a little zing, etc.

But Murray’s story is equally interesting to me when seen in light of two themes that reoccur throughout the history of dance: humiliation and snobbery. Many dancers—Bob Fosse and Twyla Tharp among them—spend a part of their lives hiding from their friends and family and colleagues the fact that they dance. To admit that you’re a practitioner of the leaping arts is to open yourself to inspection on the fronts of economic status, carnality, taste, self-involvement, and body mass. For men, of course, the tendency to waft one’s person through space, be it for monetary gain or simply for enjoyment, is especially psychologically tender. Though typically the forces of antagonism here are bound up in notions of masculinity, sometimes they are more class-based: when in 1924 Kathryn introduced Arthur to her father on their first date, the father asked the young suitor what he did for a living. Murray chose not to mention that he had already put away $10,000 in the bank or that he drove a Rolls-Royce, but instead simply said that he danced. Kathryn’s father responded, “I do, too, but what do you do for a living?”

* * *

Whenever insecurity is much in evidence in a particular arena of activity—I’m looking at you, fashion, royal courts, glossy magazines, high-end restaurants—that arena’s denizens will, in an effort to ease anxiety, create or pay heed to easily recognizable protocols and brand names; e.g., your friend didn’t just spend $900 on shoes, she spent $900 on Manolo Blahniks. Murray’s uncanny talent as a salesman saw him both combating and employing this humiliation/snobbery axis. On the former front, he had great success selling mail-order dance instruction: customers could buy paper “footprints” that you’d put on the floor and step on. The footprints had markings that corresponded to directions in a booklet. His book How to Become a Good Dancer had you trace your own shoes onto paper, and then make five copies of your “feet.” Murray encouraged you to dance alone at first, until you got up and running. Imagine the relief that a pathologically shy, aspiring dancer would feel, knowing that he wouldn’t have to go to a studio and endure the gaze of others.

More tellingly yet, Murray the advertiser was not above speaking to a potential customer’s insecurities. “Most people lack confidence,” he told his wife. “Subconsciously, they would like to have more friends and be more popular, but they don’t openly recognize this desire.” When writing ad copy for his dance studios, Murray and his wife—one waggish line of criticism against Murray runs that, since Kathryn did most of the writing, Murray made his fortune “by the sweat of his frau”—sometimes mined Murray’s own travails from adolescence. An awkward evening he’d spent as a sixteen-year-old turned into an ad titled “How I Became Popular Overnight.” The ad’s copy ran, “Girls used to avoid me when I asked for a dance. Even the poorest dancers preferred to sit against the wall rather than dance with me. But I didn’t wake up until a partner left me alone standing in the middle of the floor. . . . As a social success I was a first-class failure.”

As Mrs. Murray writes in her book, “Arthur found that no man wanted to admit that he was learning to dance, but he didn’t mind saying that he was learning the rumba. It was something like the difference between saying your feet hurt and your foot hurts. We ran smart-looking ads that now sound corny, but they appealed in those days to businessmen who read New York’s leading newspapers and business journals: ‘Does your dancing say “New York” or “small town”? Where do the fastidious satisfy their craving for the up-to-the-minute dance steps and instruction? A secret? On the contrary, they happily pass the word about Arthur Murray’s delightfully modern studios where chic meet chic.’?” This ad was rigged out with pictures of attractive women; the pictures’ captions extolled these women’s good social backgrounds.

In its heyday, ballroom and its attendant glamour could take you places. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers both came from modest backgrounds, but went on to become icons of sophistication and elegance; ditto Astaire’s idols, Vernon and Irene Castle. In Murray’s case, ballroom’s power to raise one’s station in life was noticeable not only in who Murray became in his success but also in who worked for him. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, the fall of the Hapsburgs, and the upheavals of the Depression, impoverished European aristocrats were happy to take jobs as instructors at Arthur Murray studios: at one point Murray’s work staff included a baroness, several countesses, and a White Russian prince.

Pinkies: they’re for extending.

* * *