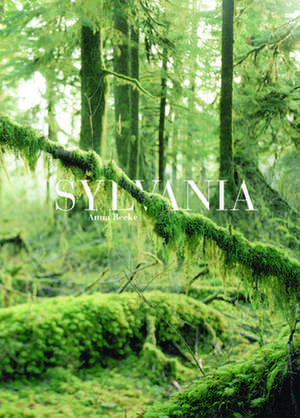

Anna Beeke: Sylvania

Fotografii de Anna Beekeen Limba Engleză Hardback – 26 oct 2015

Across cultures and centuries, the forest has occupied a unique place in our collective imagination. Sylvania, by Brooklyn-based photographer Anna Beeke (born 1984), explores the intersection of nature, imagination and myth in the American woodlands, from Washington to Vermont to Louisiana.

Anna Beeke is a documentary and fine arts photographer born in Washington, DC, and based in Brooklyn, NY. She has an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in Photography, Video, and Related Media (2013) and a Certificate from the International School of Photography in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography (2009), as well as a BA in English from Oberlin College (2007). Anna’s work has been exhibited internationally. Anna has received such honors as the 2012 Humble Arts and WIP-LTI/Lightside Materials Grant, the 2013 APA/EP Education Grant, the Alice-Beck Odette Scholarship and Alumni Scholarship Award from the School of Visual Arts, and the 2012 Film Grant from Kodak + too much chocolate. She was selected as a participant in th Eddie Adams Workshop 2009. Most recently, she was selected for Magenta's Flash Forward 2013. Anna is represented by Uprise Art.

Anna Beeke is a documentary and fine arts photographer born in Washington, DC, and based in Brooklyn, NY. She has an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in Photography, Video, and Related Media (2013) and a Certificate from the International School of Photography in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography (2009), as well as a BA in English from Oberlin College (2007). Anna’s work has been exhibited internationally. Anna has received such honors as the 2012 Humble Arts and WIP-LTI/Lightside Materials Grant, the 2013 APA/EP Education Grant, the Alice-Beck Odette Scholarship and Alumni Scholarship Award from the School of Visual Arts, and the 2012 Film Grant from Kodak + too much chocolate. She was selected as a participant in th Eddie Adams Workshop 2009. Most recently, she was selected for Magenta's Flash Forward 2013. Anna is represented by Uprise Art.

Preț: 268.13 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 402

Preț estimativ în valută:

51.32€ • 53.43$ • 43.37£

51.32€ • 53.43$ • 43.37£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17 februarie-03 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781942084051

ISBN-10: 1942084056

Pagini: 132

Ilustrații: 60 color photos

Dimensiuni: 185 x 259 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.73 kg

Editura: Daylight Books

ISBN-10: 1942084056

Pagini: 132

Ilustrații: 60 color photos

Dimensiuni: 185 x 259 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.73 kg

Editura: Daylight Books

Extras

Type of Excerpt: Contributing Text and Acknowledgments

SYLVANIA

by Anna Beeke

with words by Brian Doyle

You could walk

into the woods

anywhere, any sort

of woods, every

sort of woods, and

you would be a

different animal

within ten steps,

as soon as the

woods accepted

you, as soon as

you couldn’t hear

anything else but

the woods. We

forget that the

woods are always

there waiting. We

are afraid of the

woods and we

love the woods

and we used

to live in the

woods and some

part of us is still

fascinated and

frightened and

absorbed and

mesmerized

and yearning

secretly for

the woods. I

suppose there

will always be

woods in us

somehow until

there are no

more woods or

no more us. We came

from them as if from

a tangled green sea

and the parts of us

that are still mammal

are most comfortable

there. We forget we

are mammals. You

could walk into the

woods anywhere

and you would be

different within a

minute or two –

rattled, happier,

muddier, cautious,

more alert, home in

some way for which

we do not yet have an

excellent green word.

The densest place I have ever been in my whole life is deep in the woods here. One time I

stood on what I thought was a small hillock but it turned out to be duff ten feet deep. There

was a rumor of cougar. Of course it was raining. Of course it was. I sat down for a while

and thought about all the languages that were being spoken and had been spoken in this

one moist incredible place in the world, all the creatures of every kind who had lived here

or passed through this space, the uncountable insects, the children, the young ones of every

species. Had they gaped too, at the pillars of the trees, the bear print, the murmur of owls?

One of my six

brothers fell in love

with wood right from

the start. I remember

him handling and

fondling wood

even when he was

little. He spoke the

language of it. He

and wood liked each

other and got along

swell. He became a

forester and planted

trees, hundreds of

thousands of trees.

Do you know you

can plant a tree in

five seconds if you

get your stride right

and reach with one

hand and poke a

hole in the skin of

the earth and reach

up for the seedling

from your pack

with the other and

drop the seedling

and secure it in the

hole with your foot

as you continue on

apace? You can do

that. In some places

the woods are taking

over where farms

used to be. That

is happening in

Vermont and Maine.

When the woods

come back so do

animals that were

thought long gone,

like fisher and lion.

All the rest of his

life my brother has

worked with wood.

He built houses and

beds and chairs and

tables and desks

and cabinets and

counters and lovely

long curving tavern

bars and pretty

much anything else

you can imagine

you could persuade

from wood. In his

wood-shop there are

chunks of twenty

kinds of wood.

One time I asked

him what he was

going to do with a

particularly weighty

chunk and he said

he was waiting for

the wood to tell him

what it wanted to

be. I think about

that remark a lot

and always come

away refreshed by

the respect and

humility in it. More

and more these days

I think humility is

the final frontier.

We spend many

years building ego

and then if we are

lucky we realize

we need to cut it

down and saw it

up and turn it into

something shy.

Q: Do trees think and feel?

A: Of course not, not in any way that we know the words think and feel. But that’s the point, isn’t it? I suggest that they consider and ponder and absorb and apprehend the world in very different ways than we do, and we do not quite understand the verb of their lives. We think of them as nouns, stationary, serene, placid, substantive, stolid, stern; but imagine if you could absorb nutrition from the very earth with your intricate spidery toes. Imagine that you could eat light and sip clouds. Imagine if you too lived to be five thousand years old, like bristlecone pines, or were four hundred feet tall, like redwoods, or weighed a thousand tons, like sequoias, or spent your life on a ridge above the lithe Wilson River as it made its way toward mother Ocean. How does the tree perceive the river? Like an ouzel that never stops singing? How does the tree consider its companions? Do their roots tangle and tease? What do they feel? Because we cannot understand how they could feel, does that mean that they do not feel? If you do not know a thing, does that mean the thing is impossible? No? Well, then…

When I was a little kid

I thought that lakes

were like huge blue and

green and brown eyes in

the forest, and once in

a while, even now, all

these years later, when

I achieve childishness

again, fitfully and

delightedly – I still do.

No one more admires what it is we do with wood. We build schools and chapels and churches and houses and homes and cabins and sheds and bridges and roads and trails and paths and desks and bars and barrels and buckets and shingles and shakes and boxes and rinks and frames and steps and stairs and crosses and crucifixes and boats and ships and carts and wagons and hoops and bows and arrows and roofs and bins and shims and coffins and I could continue this sentence for a week. But probably you are like me, and every once in a while, when you see a pile of logs, they look awfully like corpses, don’t they? Just for an instant? And so they are.

I think we are absorbed by forests and woods and thickets and copses and wilderness in general because shadows and flickering light are dangerous and alluring and mysterious. There are stories in the shadows, in the forest, flitting through the trees. How many legends and fables and myths are set in the forest? The forest is where possible lives. The forest is beyond the reach of sense and reason. The forest is not a place for logic and culture and civilized opinion. The forest is ancient and itself. The forest is hidden life and deeper secrets. Anything might live there and probably does and the only way to find out is to slip in beneath the eaves and vanish into it in exactly the same way you vanish into a story.

As a species, said the late great Peter Matthiessen once, we are just down from the trees. We used to live in the trees. We forget that. We came down from the trees and out onto the savannah and we are still afraid of death. We are still filled with fear. That’s why we are so violent. We lash out. What if our moral evolution ever caught up to our astounding physical evolution? What then?

The biggest tree I ever

saw personally myself, on

foot, not from the road

with other sightseers and

erudite rangers and park

authorities, was a spruce

on the Oregon coast. You

wouldn’t believe how fat

and tall this tree was. It

was so much bigger than

your house that your house

would quail a little if they

were on the bus together. It

had been measured, and its

weight and age estimated,

and it had been entered in

registers of huge trees, and it

was sort of famous, I guess,

but I am here to tell you that

numbers slid off this thing

like small vulgar jokes. This

sylvan creature – for creature

it was, alive and sentient and

digesting sun from above

and minerals from below and

water from the mist – was so

big that when people saw it

for the first time they went

silent. How people looked

when they saw it for the first

time is what we mean when

we say awe, it seems to me.

I try to never forget that trees are

verbs always headed up. They

yearn, they elevate, they rise,

they ascend, they have a major

sun jones, they set their feet and

then jump verrrrrrrrrrrry slowly,

like the tallest slenderest toughest

rough-skinned quietest basketball

players you ever saw.

You can’t stop the wonder with which people

gawk and gape at trees. Even if you know there

are no trees beyond the fringe, even if you are

absolutely sure of that, even if there’s nothing

there but the awful battlefield detritus of a

clear-cut, you drive along through the trees

that are there, gazing at them with respect and

awe and affection. They are our cousins, our

teammates, our ancient teachers. You can learn

a great deal about fit and peace and endurance

and dignity and patience from trees.

I have.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Bringing a first book to fruition requires a great deal of support and encouragement, and I am filled with incalculable gratitude toward all the wonderful people who have helped make this possible. I am deeply grateful to Brian Doyle for his words – for seeing what I am trying to express in my own medium, and for giving it a complementary form in his. Further, I would like to thank him for writing the bewitching novel Mink River, which I picked up on San Juan Island in the early stages of shooting Sylvania and which became an unexpected muse in my search for the magical undercurrents of reality. For insight and guidance along the way, I am particularly indebted to Elisabeth Biondi, Elinor Carruci, Marvin Heiferman, Andrew Moore, Gus Powell, Charles Traub, Kiki Bauer, Bonnie Yochelson, and my peers at the School of Visual Arts. Thank you for your candid critique and inspiration. For supporting the creation of this body of work and its transformation into a book, I am infinitely thankful to the following individuals and institutions:

Humble Arts Foundation and LTI/ Lightside, the School of Visual Arts and the SVA Alumni Society, Uprise Art, American Photographic Artists, Douglas Drysdale, Mary Drysdale, Martha Peters, Howard Chua-Eon, Rob Lancefield, Hanna and Jacob Kaufman, Giorgio Furioso, David Carmen, Aidan Joseph, Dov Harel, Torre Johnson, Maxwell Mackenzie and Rebecca Cross, Suzanne Resnick, Peter J. Cohen, John Keon, Amy McIntosh and Jeffrey Toobin, Mary Schmidt, Kaye and Bob Wertz, Michael Dabney, Jim McCarthy, Etan Fraiman, and all the many, many others who pitched in. For your technical savvy, thank you Blake Ogden. For your persistent love and patience, thank you to my exceptional friends and family. I am particularly grateful to Granddad, Aunt Mary, Leeor, Alia, Corina, Hayley, my annisa family, and of course my wonderful parents – who have unflaggingly encouraged my every whim, and who inadvertently inspired this arboreal adventure. And finally, to Michael, Taj, and Ursula of Daylight, without whom this book would still be a mere dream – I am forever indebted and eternally grateful for your belief in Sylvania and for bringing it to life so beautifully.

SYLVANIA

by Anna Beeke

with words by Brian Doyle

You could walk

into the woods

anywhere, any sort

of woods, every

sort of woods, and

you would be a

different animal

within ten steps,

as soon as the

woods accepted

you, as soon as

you couldn’t hear

anything else but

the woods. We

forget that the

woods are always

there waiting. We

are afraid of the

woods and we

love the woods

and we used

to live in the

woods and some

part of us is still

fascinated and

frightened and

absorbed and

mesmerized

and yearning

secretly for

the woods. I

suppose there

will always be

woods in us

somehow until

there are no

more woods or

no more us. We came

from them as if from

a tangled green sea

and the parts of us

that are still mammal

are most comfortable

there. We forget we

are mammals. You

could walk into the

woods anywhere

and you would be

different within a

minute or two –

rattled, happier,

muddier, cautious,

more alert, home in

some way for which

we do not yet have an

excellent green word.

The densest place I have ever been in my whole life is deep in the woods here. One time I

stood on what I thought was a small hillock but it turned out to be duff ten feet deep. There

was a rumor of cougar. Of course it was raining. Of course it was. I sat down for a while

and thought about all the languages that were being spoken and had been spoken in this

one moist incredible place in the world, all the creatures of every kind who had lived here

or passed through this space, the uncountable insects, the children, the young ones of every

species. Had they gaped too, at the pillars of the trees, the bear print, the murmur of owls?

One of my six

brothers fell in love

with wood right from

the start. I remember

him handling and

fondling wood

even when he was

little. He spoke the

language of it. He

and wood liked each

other and got along

swell. He became a

forester and planted

trees, hundreds of

thousands of trees.

Do you know you

can plant a tree in

five seconds if you

get your stride right

and reach with one

hand and poke a

hole in the skin of

the earth and reach

up for the seedling

from your pack

with the other and

drop the seedling

and secure it in the

hole with your foot

as you continue on

apace? You can do

that. In some places

the woods are taking

over where farms

used to be. That

is happening in

Vermont and Maine.

When the woods

come back so do

animals that were

thought long gone,

like fisher and lion.

All the rest of his

life my brother has

worked with wood.

He built houses and

beds and chairs and

tables and desks

and cabinets and

counters and lovely

long curving tavern

bars and pretty

much anything else

you can imagine

you could persuade

from wood. In his

wood-shop there are

chunks of twenty

kinds of wood.

One time I asked

him what he was

going to do with a

particularly weighty

chunk and he said

he was waiting for

the wood to tell him

what it wanted to

be. I think about

that remark a lot

and always come

away refreshed by

the respect and

humility in it. More

and more these days

I think humility is

the final frontier.

We spend many

years building ego

and then if we are

lucky we realize

we need to cut it

down and saw it

up and turn it into

something shy.

Q: Do trees think and feel?

A: Of course not, not in any way that we know the words think and feel. But that’s the point, isn’t it? I suggest that they consider and ponder and absorb and apprehend the world in very different ways than we do, and we do not quite understand the verb of their lives. We think of them as nouns, stationary, serene, placid, substantive, stolid, stern; but imagine if you could absorb nutrition from the very earth with your intricate spidery toes. Imagine that you could eat light and sip clouds. Imagine if you too lived to be five thousand years old, like bristlecone pines, or were four hundred feet tall, like redwoods, or weighed a thousand tons, like sequoias, or spent your life on a ridge above the lithe Wilson River as it made its way toward mother Ocean. How does the tree perceive the river? Like an ouzel that never stops singing? How does the tree consider its companions? Do their roots tangle and tease? What do they feel? Because we cannot understand how they could feel, does that mean that they do not feel? If you do not know a thing, does that mean the thing is impossible? No? Well, then…

When I was a little kid

I thought that lakes

were like huge blue and

green and brown eyes in

the forest, and once in

a while, even now, all

these years later, when

I achieve childishness

again, fitfully and

delightedly – I still do.

No one more admires what it is we do with wood. We build schools and chapels and churches and houses and homes and cabins and sheds and bridges and roads and trails and paths and desks and bars and barrels and buckets and shingles and shakes and boxes and rinks and frames and steps and stairs and crosses and crucifixes and boats and ships and carts and wagons and hoops and bows and arrows and roofs and bins and shims and coffins and I could continue this sentence for a week. But probably you are like me, and every once in a while, when you see a pile of logs, they look awfully like corpses, don’t they? Just for an instant? And so they are.

I think we are absorbed by forests and woods and thickets and copses and wilderness in general because shadows and flickering light are dangerous and alluring and mysterious. There are stories in the shadows, in the forest, flitting through the trees. How many legends and fables and myths are set in the forest? The forest is where possible lives. The forest is beyond the reach of sense and reason. The forest is not a place for logic and culture and civilized opinion. The forest is ancient and itself. The forest is hidden life and deeper secrets. Anything might live there and probably does and the only way to find out is to slip in beneath the eaves and vanish into it in exactly the same way you vanish into a story.

As a species, said the late great Peter Matthiessen once, we are just down from the trees. We used to live in the trees. We forget that. We came down from the trees and out onto the savannah and we are still afraid of death. We are still filled with fear. That’s why we are so violent. We lash out. What if our moral evolution ever caught up to our astounding physical evolution? What then?

The biggest tree I ever

saw personally myself, on

foot, not from the road

with other sightseers and

erudite rangers and park

authorities, was a spruce

on the Oregon coast. You

wouldn’t believe how fat

and tall this tree was. It

was so much bigger than

your house that your house

would quail a little if they

were on the bus together. It

had been measured, and its

weight and age estimated,

and it had been entered in

registers of huge trees, and it

was sort of famous, I guess,

but I am here to tell you that

numbers slid off this thing

like small vulgar jokes. This

sylvan creature – for creature

it was, alive and sentient and

digesting sun from above

and minerals from below and

water from the mist – was so

big that when people saw it

for the first time they went

silent. How people looked

when they saw it for the first

time is what we mean when

we say awe, it seems to me.

I try to never forget that trees are

verbs always headed up. They

yearn, they elevate, they rise,

they ascend, they have a major

sun jones, they set their feet and

then jump verrrrrrrrrrrry slowly,

like the tallest slenderest toughest

rough-skinned quietest basketball

players you ever saw.

You can’t stop the wonder with which people

gawk and gape at trees. Even if you know there

are no trees beyond the fringe, even if you are

absolutely sure of that, even if there’s nothing

there but the awful battlefield detritus of a

clear-cut, you drive along through the trees

that are there, gazing at them with respect and

awe and affection. They are our cousins, our

teammates, our ancient teachers. You can learn

a great deal about fit and peace and endurance

and dignity and patience from trees.

I have.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Bringing a first book to fruition requires a great deal of support and encouragement, and I am filled with incalculable gratitude toward all the wonderful people who have helped make this possible. I am deeply grateful to Brian Doyle for his words – for seeing what I am trying to express in my own medium, and for giving it a complementary form in his. Further, I would like to thank him for writing the bewitching novel Mink River, which I picked up on San Juan Island in the early stages of shooting Sylvania and which became an unexpected muse in my search for the magical undercurrents of reality. For insight and guidance along the way, I am particularly indebted to Elisabeth Biondi, Elinor Carruci, Marvin Heiferman, Andrew Moore, Gus Powell, Charles Traub, Kiki Bauer, Bonnie Yochelson, and my peers at the School of Visual Arts. Thank you for your candid critique and inspiration. For supporting the creation of this body of work and its transformation into a book, I am infinitely thankful to the following individuals and institutions:

Humble Arts Foundation and LTI/ Lightside, the School of Visual Arts and the SVA Alumni Society, Uprise Art, American Photographic Artists, Douglas Drysdale, Mary Drysdale, Martha Peters, Howard Chua-Eon, Rob Lancefield, Hanna and Jacob Kaufman, Giorgio Furioso, David Carmen, Aidan Joseph, Dov Harel, Torre Johnson, Maxwell Mackenzie and Rebecca Cross, Suzanne Resnick, Peter J. Cohen, John Keon, Amy McIntosh and Jeffrey Toobin, Mary Schmidt, Kaye and Bob Wertz, Michael Dabney, Jim McCarthy, Etan Fraiman, and all the many, many others who pitched in. For your technical savvy, thank you Blake Ogden. For your persistent love and patience, thank you to my exceptional friends and family. I am particularly grateful to Granddad, Aunt Mary, Leeor, Alia, Corina, Hayley, my annisa family, and of course my wonderful parents – who have unflaggingly encouraged my every whim, and who inadvertently inspired this arboreal adventure. And finally, to Michael, Taj, and Ursula of Daylight, without whom this book would still be a mere dream – I am forever indebted and eternally grateful for your belief in Sylvania and for bringing it to life so beautifully.

Descriere

Sylvania explores the intersection of nature, imagination and myth in the American woodlands, from Washington to Vermont to Louisiana.