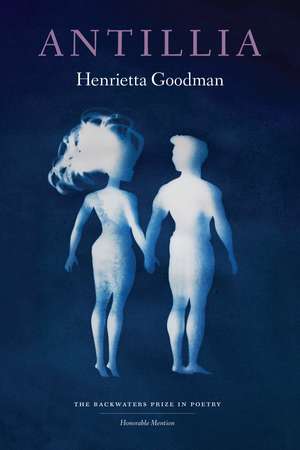

Antillia: The Backwaters Prize in Poetry Honorable Mention

Autor Henrietta Goodmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – mar 2024

The title poem of this collection refers to the phantom island of Antillia, included on maps in the fifteenth century but later found not to exist. The ghosts that haunt this collection are phantom islands, moon lakes, lasers used to clean the caryatids at the Acropolis, earlier versions of the self, suicides, a madam from the Old West, petroleum, snapdragons, pets, ice apples, Casper, and a “resident ghost” who makes the domestic realm of “the cradle and the bed” uninhabitable. The ghosts are sons, fathers “asleep in front of the TV,” and a variety of exes—“lost boys” with names like The Texan and Mr. No More Cowboy Hat whom Henrietta Goodman treats with snarky wit but also with grief, guilt, and love.

Although memories pervade this collection, these poems also look forward and outward into a world where social inequality and environmental disaster meet the possibility of metamorphosis.

Preț: 91.96 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.60€ • 18.34$ • 14.57£

17.60€ • 18.34$ • 14.57£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496236081

ISBN-10: 1496236084

Pagini: 94

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 5 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: The Backwaters Press

Colecția The Backwaters Press

Seria The Backwaters Prize in Poetry Honorable Mention

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496236084

Pagini: 94

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 5 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: The Backwaters Press

Colecția The Backwaters Press

Seria The Backwaters Prize in Poetry Honorable Mention

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Henrietta Goodman is an assistant professor of English at Rocky Mountain College in Billings, Montana. She is the author of All That Held Us, Hungry Moon, and Take What You Want.

Extras

The Puppy and Kitten Channel

Remember the night I passed my test

and the Thai place where you took me

brought my rice pressed into the shape

of a heart, a maraschino cherry bleeding

sweetly on the top? It’s an old story—once

there was an atom who wanted to

be a molecule. I’ve thought a lot about

innocence since then—the sleeping otters

floating on their backs in the aquarium

pool, paws linked, the human presence

behind the animal videos on the Internet—

intimate laughter, murmured words

in Russian or Norwegian while puppies

lick each other’s faces or a baby deer

eats from someone’s hand. I’ve watched

the puppy and kitten channel. At the Origami

Club, you can learn to make a whole paper

world—origami strawberry shortcake,

origami water bug, origami chicken

hatching from an egg. Do you ever feel

completely ruined? The man with no arms

and no legs takes an egg into his mouth

and drops it into a bowl, takes a whisk

into his mouth and scrambles, takes

the bowl into his mouth and wheels

to the stove, takes a spatula into his mouth

and lifts the egg onto a plate, bits

of shell and all. Takes a fork into his

mouth. Turns and grins. Do you feel

ruined now? Yes, still ruined, and guilty.

Click again, and a couple laughs as a kitten

and a bunny tumble across a flowered

rug. The otters float apart, then back

together. The origami bride smooths

a wrinkle in her immaculate dress.

What Are We Going to Turn Into?

When he was four or five, my son would sometimes ask.

As if these bodies were not our final form. As if nature

or magic might deliver us. Too shy to sing at the Christmas

concert, to clap or shape his fingers into antlers or falling

snow, his hair a blond wave like Hermey the Elf’s. When

one of my professors told me the only neighborhood I could

afford wasn’t safe, he meant it wasn’t white. I stepped

barefoot onto the porch to call my son for dinner and the door

locked behind me. My neighbors came home, and while

I gestured, not knowing how to say locked out or anything

else in Spanish, the man put down his groceries, crossed

my yard, removed the ac unit from my window, picked up

my son and boosted him through. I stood there repeating

gracias. I thought the people on that street might not want

us there—and they passed plates of burgers and potato salad

and chocolate cake over the fence, and Ivan’s mother told him

to give the toys he had outgrown to my son—so many dinosaurs—

and I know I wasn’t anything but lucky, but even the desperate

man who knocked on my door at 2:00 a.m. to try to sell a pair

of boots apologized for waking me and didn’t punch through

the window. I wish I could say that when Jeremiah’s grandmother

came down the street and put out her hand, I wasn’t so aware

of mine—so soft, so small, so white. Almost ten years gone

from Lubbock, and last night my son brought from his father’s

house a green caterpillar his father threw on an anthill. My son

reached for it, swatted the ants that climbed his arm, made it

a home with dirt and pink blossoms and leaves and sticks

in a plastic cup labeled St. Patrick’s Hospital from the week

he spent there trying not to want to die, and I’m thinking

of how Gabriel’s father used to go around shirtless with huge

muscles and a huge grin calling my son Casper, how we laughed

together, and I’m thinking about that question, based on

the simplest metaphor I know, the only one that matters.

Remember the night I passed my test

and the Thai place where you took me

brought my rice pressed into the shape

of a heart, a maraschino cherry bleeding

sweetly on the top? It’s an old story—once

there was an atom who wanted to

be a molecule. I’ve thought a lot about

innocence since then—the sleeping otters

floating on their backs in the aquarium

pool, paws linked, the human presence

behind the animal videos on the Internet—

intimate laughter, murmured words

in Russian or Norwegian while puppies

lick each other’s faces or a baby deer

eats from someone’s hand. I’ve watched

the puppy and kitten channel. At the Origami

Club, you can learn to make a whole paper

world—origami strawberry shortcake,

origami water bug, origami chicken

hatching from an egg. Do you ever feel

completely ruined? The man with no arms

and no legs takes an egg into his mouth

and drops it into a bowl, takes a whisk

into his mouth and scrambles, takes

the bowl into his mouth and wheels

to the stove, takes a spatula into his mouth

and lifts the egg onto a plate, bits

of shell and all. Takes a fork into his

mouth. Turns and grins. Do you feel

ruined now? Yes, still ruined, and guilty.

Click again, and a couple laughs as a kitten

and a bunny tumble across a flowered

rug. The otters float apart, then back

together. The origami bride smooths

a wrinkle in her immaculate dress.

What Are We Going to Turn Into?

When he was four or five, my son would sometimes ask.

As if these bodies were not our final form. As if nature

or magic might deliver us. Too shy to sing at the Christmas

concert, to clap or shape his fingers into antlers or falling

snow, his hair a blond wave like Hermey the Elf’s. When

one of my professors told me the only neighborhood I could

afford wasn’t safe, he meant it wasn’t white. I stepped

barefoot onto the porch to call my son for dinner and the door

locked behind me. My neighbors came home, and while

I gestured, not knowing how to say locked out or anything

else in Spanish, the man put down his groceries, crossed

my yard, removed the ac unit from my window, picked up

my son and boosted him through. I stood there repeating

gracias. I thought the people on that street might not want

us there—and they passed plates of burgers and potato salad

and chocolate cake over the fence, and Ivan’s mother told him

to give the toys he had outgrown to my son—so many dinosaurs—

and I know I wasn’t anything but lucky, but even the desperate

man who knocked on my door at 2:00 a.m. to try to sell a pair

of boots apologized for waking me and didn’t punch through

the window. I wish I could say that when Jeremiah’s grandmother

came down the street and put out her hand, I wasn’t so aware

of mine—so soft, so small, so white. Almost ten years gone

from Lubbock, and last night my son brought from his father’s

house a green caterpillar his father threw on an anthill. My son

reached for it, swatted the ants that climbed his arm, made it

a home with dirt and pink blossoms and leaves and sticks

in a plastic cup labeled St. Patrick’s Hospital from the week

he spent there trying not to want to die, and I’m thinking

of how Gabriel’s father used to go around shirtless with huge

muscles and a huge grin calling my son Casper, how we laughed

together, and I’m thinking about that question, based on

the simplest metaphor I know, the only one that matters.

Cuprins

Acknowledgements

1

The Puppy and Kitten Channel

What Are We Going to Turn Into?

Gretel Returns

Ice Apples

Asked to Imagine the Death of My Son

Self-Portrait, 1921, Alberto Giacometti

Lake of Delight

Self-Portrait Playing Tennis

Self-Portrait with Emergency Landing

Futures

The Man behind the Curtain

Lake of Winter (Berryman)

Self-Portrait as a Stranger

Caryatids

I Want to Be a Door

Opossum of the Month

Sea of Desire

Free Association

Antillia

Lake of Death

Postcolonial Melancholia

Red-Winged Blackbirds

2

I Don’t Require Durability in a Swan

3

When Frankenstein Chased His Creature across the Ice

The Men at Snowbowl Teaching Their Daughters to Ski

The Petroleum Club

Seahorse

Organizational Systems

Self-Portrait in the Blackfoot

Self-Portrait with Northern Lights

Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers (Marc Chagall, 1912)

Lake of Time

Letter from the Ant Queen

The Repetitive Bird

Self-Portrait on Valentine’s Day

Pointillist Self-Portrait

Mr. No More Cowboy Hat

Letter from the Queen of the Crows

Remember What You Said About Women

Lake of Hope

Resident Ghost

The Texan

Self-Portrait in Downtown Missoula

Namaste

Source Acknowledgments

1

The Puppy and Kitten Channel

What Are We Going to Turn Into?

Gretel Returns

Ice Apples

Asked to Imagine the Death of My Son

Self-Portrait, 1921, Alberto Giacometti

Lake of Delight

Self-Portrait Playing Tennis

Self-Portrait with Emergency Landing

Futures

The Man behind the Curtain

Lake of Winter (Berryman)

Self-Portrait as a Stranger

Caryatids

I Want to Be a Door

Opossum of the Month

Sea of Desire

Free Association

Antillia

Lake of Death

Postcolonial Melancholia

Red-Winged Blackbirds

2

I Don’t Require Durability in a Swan

3

When Frankenstein Chased His Creature across the Ice

The Men at Snowbowl Teaching Their Daughters to Ski

The Petroleum Club

Seahorse

Organizational Systems

Self-Portrait in the Blackfoot

Self-Portrait with Northern Lights

Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers (Marc Chagall, 1912)

Lake of Time

Letter from the Ant Queen

The Repetitive Bird

Self-Portrait on Valentine’s Day

Pointillist Self-Portrait

Mr. No More Cowboy Hat

Letter from the Queen of the Crows

Remember What You Said About Women

Lake of Hope

Resident Ghost

The Texan

Self-Portrait in Downtown Missoula

Namaste

Source Acknowledgments

Recenzii

"Readers of this collection will have a hard time shaking the image of Antillia from the horizon of their thoughts, and they will be grateful for the haunting."—Big Sky Journal

“Henrietta Goodman’s is a poetry of testament, an ‘inventory of scars,’ a mosaic of shards and sorrows, a symphony whose movements straddle innocence and experience, whose cinematic cross-cutting of gutting images provides evidence of a wise spirit bruised yet irrepressible. Antillia gestures toward a taxing history of embodied travails, of ice apples, and ghosts, a lived terrain where Goodman sees ‘everything/trying to divide yet stay attached/at the root.’ Here’s a voice gritty, delicate, resilient, raw, a speaker with a handsaw who’s ‘no one’s wife and no one’s martyr,’ instead ‘a gasping head on a platter/of water’ whose eyes cast floodlights on the ‘Forty billion poison gallons/the geese see from air and mistake for a safe place.’ Savvy to feel gifted when the “ground is finally thawed enough to bury the dead”; brilliant to define ‘Happiness: the underside of a dried starfish,’ Goodman reminds us that a child can be ‘made of nothing,’ and that a single word can birth a shattered world of loss and misunderstanding in which we nevertheless abide.”—Katrina Roberts, author of Likeness

“Henrietta Goodman’s Antillia is a collection of searching lyric poems that remember, joke, free associate, interrogate, worry, and examine the roots of words in pursuit of sense or solace. The world depicted is one of potential chaos and harm, though a quest for love, joy, and understanding has not been abandoned. In one Proustian meditation, the smell of Windex conjures memories of the speaker’s grade school crush, yet further consideration yields recollections of a Cold War-era bomb shelter. The bewildered (or sardonic) speaker asks, ‘Windex leads to Martin leads to beauty leads to bomb?’ The volume’s title suggests that a new world might be accessed, though at present it’s more myth than fact. These aesthetically impressive poems stun with their vigor, candor, and wit.”—Christopher Brean Murray, author of Black Observatory: Poems

“‘In the South, everything bites / and f*cks and pretends not to,’ Henrietta Goodman writes in one of her trademark poems that are alive and daring and nervy: all heart and smarts, no pretense. We’re so fortunate to have this new book, which moves from lovers to sons to metaphorical-real lakes to a fancy cowboy bar’s ‘ropes / of neon acrylic squeezed straight from the tube’ to fine art to stinging truths—insisting on loving and facing head-on a world that keeps failing and falling.”—Alexandra Teague, author of Or What We’ll Call Desire

Descriere

Although ghosts of all kinds haunt this collection, these poems also look forward and outward into a world where social inequality and environmental disaster meet the possibility of metamorphosis.