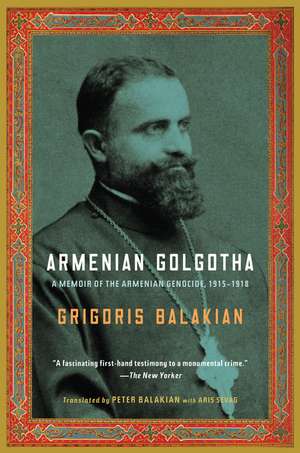

Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918

Autor Grigoris Balakian Traducere de Peter Balakian, Aris Sevagen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

Armenian Golgotha is Balakian’s devastating eyewitness account—a haunting reminder of the first modern genocide and a controversial historical document that is destined to become a classic of survivor literature.

Preț: 131.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 197

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.18€ • 26.41$ • 20.96£

25.18€ • 26.41$ • 20.96£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096770

ISBN-10: 1400096774

Pagini: 509

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W; 5 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 167 x 235 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400096774

Pagini: 509

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W; 5 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 167 x 235 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Born in 1876, Grigoris Balakian was one of the leading Armenian intellectuals of his generation. In Ottoman Turkey he attended Armenian schools and seminary; and in Germany he studied, at different times, engineering and theology. He was one of the 250 cultural leaders (intellectuals, clergy, teachers, and political and community leaders) arrested by the Turkish government on the night of April 24, 1915, and deported to the interior. Unlike the vast majority of his conationals, he survived nearly four years in the killing fields. Ordained as a celibate priest (vartabed) in 1901, he later became a bishop and prelate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in southern France. He is the author of various books and monographs (some of them lost) on Armenian culture and history, including The Ruins of Ani (1910) and Armenian Golgotha, volume 1 (1922) and volume 2 (1959). He died in Marseilles in 1934.

Peter Balakian is the author of The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’ s Response, winner of the 2005 Raphael Lemkin Prize, a New York Times best seller, and a New York Times Notable Book; and of Black Dog of Fate, winner of the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for the Art of Memoir, also a New York Times Notable Book. Grigoris Balakian was his great-uncle.

Peter Balakian is the author of The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’ s Response, winner of the 2005 Raphael Lemkin Prize, a New York Times best seller, and a New York Times Notable Book; and of Black Dog of Fate, winner of the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for the Art of Memoir, also a New York Times Notable Book. Grigoris Balakian was his great-uncle.

Extras

The Night of Gethsemane

On the night of Saturday, April 11/24, 1915, the Armenians of the capital city, exhausted from the Easter celebrations that had come to an end a few days earlier, were snoring in a calm sleep. Meanwhile on the heights of Stambul, near Ayesofia, a highly secret activity was taking place in the palatial central police station.

Groups of Armenians had just been arrested in the suburbs and neighborhoods of the capital; blood-colored military buses were now transporting them to the central prison. Weeks earlier Bedri,* chief of police in Constantinople, had sent official sealed orders to all the guardhouses, with the instruction that they not be opened until the designated day and that they then be carried out with precision and in secrecy. The orders were warrants to arrest the Armenians whose names were on the blacklist, a list compiled with the help of Armenian traitors, particularly Artin Megerdichian, who worked with the neighborhood Ittihad

clubs.† Condemned to death were Armenians who were prominent and active in either revolutionary or nonpartisan Armenian organizations and who were deemed liable to incite revolution or resistance.‡

On this Saturday night I, along with eight friends from Scutari, was transported by a small steamboat from the quay of the huge armory of Selimiye to Sirkedji. The night smelled of death; the sea was rough, and our hearts were full of terror. We prisoners were under strict police guard, not allowed to speak to one another. We had no idea where we were going.

We arrived at the central prison, and here behind gigantic walls and large bolted gates, they put us in a wooden pavilion in the courtyard, which was said by some to have once served as a school. We sat there, quiet and somber, on the bare wooden floor under the faint light of a flickering lantern, too stunned and confused to make sense of what was happening.

We had barely begun to sink into fear and despair when the giant iron gates of the prison creaked open again and a multitude of new faces were pushed inside. They were all familiar faces—revolutionary and political leaders, public figures, and nonpartisan and even antipartisan intellectuals.

From the deep silence of the night until morning, every few hours Armenians were brought to the prison. And so behind these high walls, the jostling and commotion increased as the crowd of prisoners became denser. It was as if all the prominent Armenian public figures—assemblymen, representatives, revolutionaries, editors, teachers, doctors, pharmacists, dentists, merchants, bankers, and others in the capital city—had made an appointment to meet in these dim prison cells. Some even appeared in their nightclothes and slippers. The more those familiar faces kept appearing, the more the chatter abated and our anxiety grew.

Before long everyone looked solemn, our hearts heavy and full of worry about an impending storm. Not one of us understood why we had been arrested, and no one could assess the consequences. As the night’s hours slipped by, our distress mounted. Except for a few rare stoics, we were in a state of spiritual anguish, terrified of the unknown and longing for comfort.

Right through till morning new Armenian prisoners arrived, and each time we heard the roar of the military cars, we hurried to the windows to see who they were. The new arrivals had contemptuous smiles on their faces, but when they saw hundreds of other well-known Armenians old and young around them, they too sank into fear. We were all searching for answers, asking what all of this meant, and pondering our fate.

*See Biographical Glossary.

†Meeting places for members of the local Ittihad Party committees throughout the empire.—trans.

‡Revolutionary here refers to reform-oriented political workers.—trans.

From the Hardcover edition.

On the night of Saturday, April 11/24, 1915, the Armenians of the capital city, exhausted from the Easter celebrations that had come to an end a few days earlier, were snoring in a calm sleep. Meanwhile on the heights of Stambul, near Ayesofia, a highly secret activity was taking place in the palatial central police station.

Groups of Armenians had just been arrested in the suburbs and neighborhoods of the capital; blood-colored military buses were now transporting them to the central prison. Weeks earlier Bedri,* chief of police in Constantinople, had sent official sealed orders to all the guardhouses, with the instruction that they not be opened until the designated day and that they then be carried out with precision and in secrecy. The orders were warrants to arrest the Armenians whose names were on the blacklist, a list compiled with the help of Armenian traitors, particularly Artin Megerdichian, who worked with the neighborhood Ittihad

clubs.† Condemned to death were Armenians who were prominent and active in either revolutionary or nonpartisan Armenian organizations and who were deemed liable to incite revolution or resistance.‡

On this Saturday night I, along with eight friends from Scutari, was transported by a small steamboat from the quay of the huge armory of Selimiye to Sirkedji. The night smelled of death; the sea was rough, and our hearts were full of terror. We prisoners were under strict police guard, not allowed to speak to one another. We had no idea where we were going.

We arrived at the central prison, and here behind gigantic walls and large bolted gates, they put us in a wooden pavilion in the courtyard, which was said by some to have once served as a school. We sat there, quiet and somber, on the bare wooden floor under the faint light of a flickering lantern, too stunned and confused to make sense of what was happening.

We had barely begun to sink into fear and despair when the giant iron gates of the prison creaked open again and a multitude of new faces were pushed inside. They were all familiar faces—revolutionary and political leaders, public figures, and nonpartisan and even antipartisan intellectuals.

From the deep silence of the night until morning, every few hours Armenians were brought to the prison. And so behind these high walls, the jostling and commotion increased as the crowd of prisoners became denser. It was as if all the prominent Armenian public figures—assemblymen, representatives, revolutionaries, editors, teachers, doctors, pharmacists, dentists, merchants, bankers, and others in the capital city—had made an appointment to meet in these dim prison cells. Some even appeared in their nightclothes and slippers. The more those familiar faces kept appearing, the more the chatter abated and our anxiety grew.

Before long everyone looked solemn, our hearts heavy and full of worry about an impending storm. Not one of us understood why we had been arrested, and no one could assess the consequences. As the night’s hours slipped by, our distress mounted. Except for a few rare stoics, we were in a state of spiritual anguish, terrified of the unknown and longing for comfort.

Right through till morning new Armenian prisoners arrived, and each time we heard the roar of the military cars, we hurried to the windows to see who they were. The new arrivals had contemptuous smiles on their faces, but when they saw hundreds of other well-known Armenians old and young around them, they too sank into fear. We were all searching for answers, asking what all of this meant, and pondering our fate.

*See Biographical Glossary.

†Meeting places for members of the local Ittihad Party committees throughout the empire.—trans.

‡Revolutionary here refers to reform-oriented political workers.—trans.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A fascinating first-hand testimony to a monumental crime.”

—The New Yorker

“Gripping. . . . A powerful and important book. . . . It takes its place as one of the key first-hand sources for understanding the Armenian Genocide.”

—Mark Mazower, The New Republic

“Powerful. . . . Riveting. . . . A poignant, often harrowing story about the resiliency of the human spirit [and] a window on a moment in history that most Americans only dimly understand.”

—Chris Bohjalian, Washington Post

“An immensely moving, harrowing memoir that instantly takes its place as a classic alongside Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz and Elie Wiesel’s Night.”

—Carlin Romano, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“Read this heartbreaking book. Armenian Golgotha describes the suffering, agony and massacre of innumerable Armenian families almost a century ago; its memory must remain a lesson for more than one generation.”

—Elie Wiesel, author of Night

“An appalling and magnificent book. . . . It owes its existence to [Balakian’s] determination to survive to write it . . . a sacred task that gives him the strength to persevere through the impossible circumstances that killed well over a million of his countrymen.”

—Benjamin Moser, Harper’s

“Shocking and brilliant. . . . Exquisitely rendered. . . . This book has the feel of a classic about it, and I suspect that future writers on historical trauma and its representation will turn eagerly to Armenian Golgotha. It’s a massively important contribution to this field.”

—Jay Parini, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“An extraordinary narrative . . . beautifully translated. . . . Armenian Golgotha will influence Armenian genocide studies for decades.”

—John A. C. Greppin, The Times Literary Supplement (London)

“Monumental. . . . Balakian provides strong evidence that these gruesome proceedings were carried out under official orders from the highest level. . . . For generations to come Armenian Golgotha will remain a first-hand documentation of a historic tragedy written from the perspective of a talented scholar.”

—Henry Morgenthau, III, Boston Sunday Globe

“[A work] of exceptional interest and scholarship.”

—Christopher Hitchens, Slate

“The translation and publication of Armenian Golgotha in English is long overdue. It constitutes a thundering historical proof that those who deny the Armenian Genocide are engages in a massive deception.”

—Deborah E. Lipstadt, author of Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory

“Groundbreaking. . . . Comprehensive. . . . Sobering. . . . Armenian Golgotha is replete with narratives that focus on collective suffering, marking this memoir as one of the few to explicate the true nature of the crime. . . . Balakian’s memory is extraordinary, but so, too, are his intellect, his compassion and his ethical obligation to immortalize his beloved co-nationals.”

—Donna-Lee Frieze, The Jewish Daily Forward

“An Armenian equivalent to the testimonies of Holocaust survivors like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.”

—Adam Kirsch, Nextbook

“The descriptions of the Armenian genocide are striking and the author spares his readers none of the gruesome details. . . . A riveting and powerful indictment of a genocide that became a paradigm for future genocides.”

—Holger H. Herwig, The Gazette (Montreal)

“An essential memoir, a lively and extraordinary life story. . . . This is more than an eyewitness account, it is a masterful history in its own right.”

—Seth J. Frantzman, The Jerusalem Post

“Weighted with eyewitness accounts and distinguished by Balakian’s prodigiously sharp memory, this book is not a scholar’s history, of course, but an educated prelate’s, with an enviable grasp of Ottoman and European history. . . . Memory and hope for the future live in seminal texts such as Armenian Golgotha.”

—Keith Garebian, The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“A powerful, moving account of the Armenian Genocide, a story that needs to be known, and is told here with a sweep of experience and wealth of detail that is as disturbing as it is irrefutable.”

—Sir Martin Gilbert

“Extraordinary. . . . This book will become a classic, both for its depiction of a much denied genocide and its humane and brilliant witness to what human beings can endure and overcome.”

—Robert Jay Lifton, author of The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide

“Witness literature of the highest order, to be put aside the great testimony from the Shoah. . . . Required reading for those who wish to comprehend the 20th century.”

—Robert Leiter, The Jewish Exponent

“An astonishing memoir. . . . An important primary document concerning the Armenian Genocide. . . . A major addition to the literature of witness and testimony.”

—Robert Melson, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal

—The New Yorker

“Gripping. . . . A powerful and important book. . . . It takes its place as one of the key first-hand sources for understanding the Armenian Genocide.”

—Mark Mazower, The New Republic

“Powerful. . . . Riveting. . . . A poignant, often harrowing story about the resiliency of the human spirit [and] a window on a moment in history that most Americans only dimly understand.”

—Chris Bohjalian, Washington Post

“An immensely moving, harrowing memoir that instantly takes its place as a classic alongside Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz and Elie Wiesel’s Night.”

—Carlin Romano, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“Read this heartbreaking book. Armenian Golgotha describes the suffering, agony and massacre of innumerable Armenian families almost a century ago; its memory must remain a lesson for more than one generation.”

—Elie Wiesel, author of Night

“An appalling and magnificent book. . . . It owes its existence to [Balakian’s] determination to survive to write it . . . a sacred task that gives him the strength to persevere through the impossible circumstances that killed well over a million of his countrymen.”

—Benjamin Moser, Harper’s

“Shocking and brilliant. . . . Exquisitely rendered. . . . This book has the feel of a classic about it, and I suspect that future writers on historical trauma and its representation will turn eagerly to Armenian Golgotha. It’s a massively important contribution to this field.”

—Jay Parini, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“An extraordinary narrative . . . beautifully translated. . . . Armenian Golgotha will influence Armenian genocide studies for decades.”

—John A. C. Greppin, The Times Literary Supplement (London)

“Monumental. . . . Balakian provides strong evidence that these gruesome proceedings were carried out under official orders from the highest level. . . . For generations to come Armenian Golgotha will remain a first-hand documentation of a historic tragedy written from the perspective of a talented scholar.”

—Henry Morgenthau, III, Boston Sunday Globe

“[A work] of exceptional interest and scholarship.”

—Christopher Hitchens, Slate

“The translation and publication of Armenian Golgotha in English is long overdue. It constitutes a thundering historical proof that those who deny the Armenian Genocide are engages in a massive deception.”

—Deborah E. Lipstadt, author of Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory

“Groundbreaking. . . . Comprehensive. . . . Sobering. . . . Armenian Golgotha is replete with narratives that focus on collective suffering, marking this memoir as one of the few to explicate the true nature of the crime. . . . Balakian’s memory is extraordinary, but so, too, are his intellect, his compassion and his ethical obligation to immortalize his beloved co-nationals.”

—Donna-Lee Frieze, The Jewish Daily Forward

“An Armenian equivalent to the testimonies of Holocaust survivors like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.”

—Adam Kirsch, Nextbook

“The descriptions of the Armenian genocide are striking and the author spares his readers none of the gruesome details. . . . A riveting and powerful indictment of a genocide that became a paradigm for future genocides.”

—Holger H. Herwig, The Gazette (Montreal)

“An essential memoir, a lively and extraordinary life story. . . . This is more than an eyewitness account, it is a masterful history in its own right.”

—Seth J. Frantzman, The Jerusalem Post

“Weighted with eyewitness accounts and distinguished by Balakian’s prodigiously sharp memory, this book is not a scholar’s history, of course, but an educated prelate’s, with an enviable grasp of Ottoman and European history. . . . Memory and hope for the future live in seminal texts such as Armenian Golgotha.”

—Keith Garebian, The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“A powerful, moving account of the Armenian Genocide, a story that needs to be known, and is told here with a sweep of experience and wealth of detail that is as disturbing as it is irrefutable.”

—Sir Martin Gilbert

“Extraordinary. . . . This book will become a classic, both for its depiction of a much denied genocide and its humane and brilliant witness to what human beings can endure and overcome.”

—Robert Jay Lifton, author of The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide

“Witness literature of the highest order, to be put aside the great testimony from the Shoah. . . . Required reading for those who wish to comprehend the 20th century.”

—Robert Leiter, The Jewish Exponent

“An astonishing memoir. . . . An important primary document concerning the Armenian Genocide. . . . A major addition to the literature of witness and testimony.”

—Robert Melson, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal