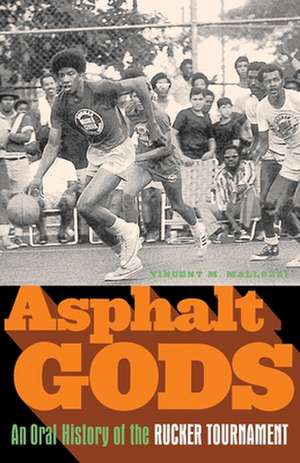

Asphalt Gods: An Oral History of the Rucker Tournament

Autor Vincent M. Mallozzien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2003

Earl “The Goat” Manigault. Herman “Helicopter” Knowings. Joe “The Destroyer” Hammond. Richard “Pee Wee” Kirkland. These and dozens of other colorfully nicknamed men are the “Asphalt Gods,” whose astounding exploits in the Rucker Tournament, often against multimillionaire NBA superstars, have made them playground divinity. First established in the 1950s by Holcombe Rucker, a New York City Parks Department employee, the tournament has grown to become a Harlem institution, an annual summer event of major proportions. On that fabled patch of concrete, unknown players have been lighting it up for decades as they express basketball as a freestyle art among their peers and against such pro immortals as Julius Erving and Wilt Chamberlain. X’s and O’s are exchanged for oohs and aahs in one of the great examples of street theater to be found in urban America.

Asphalt Gods is a streetwise, supremely entertaining oral history of a tournament that has influenced everything from NBA playing style to hip-hop culture. Now, legends transmitted by word of mouth find a home and the achievements of basketball’s greatest unknowns a permanent place in the game’s record.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 120.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.12€ • 23.68$ • 19.24£

23.12€ • 23.68$ • 19.24£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 februarie-12 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385520997

ISBN-10: 0385520999

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Doubleday Books

ISBN-10: 0385520999

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Doubleday Books

Notă biografică

VINCENT MALLOZZI is a native of Harlem who has become the Rucker Tournament’s unofficial historian, covering it for such publications as the New York Times, the Village Voice, the Source, Vibe, and Slam. He was recently elected to the Rucker Hall of Fame for his community service. He is a sports editor for the New York Times.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

THE PIED PIPER

On March 2, 1926, Holcombe Rucker came into a hard life. He was raised in poverty by his grandmother, Rosa Deniston, who struggled to make the rent at 141st Street and Bradhurst Avenue. He was a star guard at Benjamin Franklin High School in East Harlem, but dropped out to go off to serve in the United States Army during World War II. By the time Uncle Sam sent him home in 1946, he was a mature and extremely focused young man.

That year, Rucker came back to Harlem and earned a general equivalency high school diploma, then enrolled at CCNY, where he took night classes and needed just three years to complete a four-year bachelor of arts degree. He landed a job as a recreational director with the New York City Department of Parks; taught English at Harlem's Junior High School 139, and worked at St. Phillips, a local parish church and community center at 134th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, where he served as a basketball coach and created a basketball tournament that featured divisions made up of various age groups. The purpose of the tournament was to keep neighborhood kids off the streets and out of trouble. Through lessons learned in the discipline and dedication it took to become a winning basketball team, Rucker was able to teach his players a lot about life. Most of these players were living in poverty as well, and Rucker wanted them to make something of themselves so that they could avoid the kind of hard life he had known as a child.

Charles Turner, a Rucker disciple, played for Holcombe Rucker at St. Phillips. "I played for the Mites," Turner said, "before I graduated to the Midgets."

Turner is sixty-five now, but he "can remember like yesterday" the day his life was turned around by Rucker at halftime of a weekend game between St. Phillips and a powerhouse team from Harlem's YMCA.

At the time, Turner was a fourteen-year-old hotshot from Central Needle Trade High School with a lot of attitude but not much discipline.

"We went out on the court that day and just started clowning around, trying to make fancy passes and just do our own thing," Turner said. "We were just kids, I guess, just having fun."

At halftime, St. Phillips trailed the YMCA by 30 points. Holcombe Rucker, not smiling on this day, sat his team down in the locker room. He hesitated a moment before he spoke, his gentle eyes sweeping over every one of them. And then he let loose.

"I put all of this training into every one of you, all of this time!" Rucker shrieked. "And you're out there bullshitting?"

Rucker paused again, burning a look into his players. As he stared long and hard, tears began to stream down his cheeks.

"We were frozen scared," Turner said. "We were all tough kids from the streets. We had never seen a grown man cry before."

Rucker never said another word.

"He didn't have to," Turner said. "It was a lesson in discipline and respect that we would never forget."

Turner and his teammates went out and completely dominated the second half, grabbing every rebound, hustling for every loose ball.

"Those kids from the Y were looking at us like we were possessed or something," Turner said. "We ended up winning that game by 30 points."

Charles Turner still lives in Harlem, and so too does the memory of Holcombe Rucker, who left New York City a basketball treasure that still bears his name. The legacy of Turner's mentor is everywhere. It lives in Harlem classrooms and barrooms, in gymnasiums and living rooms, and it was alive and well one frigid day at Charles Restaurant in Harlem, just a bounce pass from Rucker Park, where Turner and Ernie Morris, a Rucker historian, were wearing sour faces over their sweet yams.

"Earl Manigault needed to be smacked, literally smacked to degrade Rucker like that," said the fifty-nine-year-old Morris, spearing his ham hocks as he spoke. "I mean, Rucker wasn't a fat guy who earned a living cleaning parks, the man was a Parks Department director who helped thousands of us Harlem kids go to college, and kept thousands more off the streets and out of jail."

On a winter's day in the basketball capital of the universe, a hot lunch is spoiled when Turner brings up the movie Rebound: The Legend of Earl "The Goat" Manigault, which was broadcast with a great deal of fanfare on HBO.

Don Cheadle plays the Goat, a high-flying dunking machine with a heroin problem who gets swallowed up by the same mean streets he once soared over (we'll hear a great deal about him in the chapters to follow). Forest Whitaker plays Holcombe Rucker, who speaks words of wisdom while standing behind a garbage pail, a broom, and a big belly.

"Earl was a consultant on the set," says Turner. "I liked the Goat a whole lot, but why did he have to describe Mr. Rucker like that to those movie people? It just didn't make any sense."

Perhaps no one knew Holcombe Rucker, the man, better than Morris and Turner, both high school hoop stars from the 1950s who learned their games under him at St. Phillips. According to them, Rucker was all about one thing, helping kids, especially troubled kids. He was not, they insist, "some fool Parks Department custodian" they had read about throughout the years in newspapers and magazines or seen portrayed on television.

"When you played ball for him, you learned to answer every one of his questions with a 'yes sir,' or a 'no sir,' " Turner said. "And don't even think about playing ball unless Mr. Rucker took a look at your report card and approved of it."

In the summer of 1946, Rucker began staging an outdoor tournament on 138th Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenues. Those early outdoor tourneys opened with four teams and one referee, Rucker himself.

In time, Rucker's vision expanded, and he began scheduling games for his playground teams against other youth organizations throughout New York City. Those who knew Rucker well say he managed his youth leagues despite a lack of cooperation from the Department of Parks, which turned its back on him. There were times, friends say, when Rucker would have to scrape up loose change to buy a whistle, and others when he had to borrow basketballs from some of the kids playing in his games.

The late John "Twenty Grand" Hunter, a dapper "street entrepreneur with his ear to the street" as one player from those days describes him, often slipped Rucker a few dollars when the going got real tight. Though Hunter earned much of his money through sports gambling on events like horse racing and football games, he was always generous with his profits where Holcombe Rucker was concerned. If Rucker's kids needed uniforms or sneakers and couldn't afford them, Hunter went deep into his pockets. Hunter also provided transportation money for players traveling to and from games, and he made sure that every car or bus that transported the players had a full tank of gas.

Ernie Morris remembers playing on those early Rucker teams, and competing against the very best that the city had to offer: "Hook or crook, Holcombe had us on the move," he said. "We played against black kids from the Bronx, Irish and Italian kids from Hell's Kitchen, anyone who wanted to give us a game."

A Date with Mary

Holcombe Rucker's hoop dream was slowly coming into focus on an April night in 1947, when a friend asked if he would do him a favor and take his date, a young woman named Mary Green, to a Billie Holiday performance at Small's Paradise Club on 135th Street and Seventh Avenue. Rucker's friend had made other plans that evening, and though he and Mary were not seriously involved, he did not want to hurt her feelings.

"But I have my own date tonight," Holcombe told his friend.

"Please," Holcombe's friend replied. "Just do me this favor, just this once."

So Holcombe took Mary to Small's, which ranked in Harlem and show business legends with the old Cotton Club and the Savoy Ballroom. It was the place where Harlem's elite gathered for good times when talents like Holiday, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Billy Eckstine, Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Bill Robinson dominated the stage.

"Holcombe had a date and told her to meet him there," Mary Rucker Thomas recently recalled. "But when his girlfriend came in, I guess she saw us together, and she just went and sat somewhere else."

And Mary's original date?

"He just never showed up, and Holcombe knew he wasn't going to," she recalled. "So Holcombe just stayed there with me and we listened to Billie Holiday together. I thought to myself, 'Here's a real nice guy.' "

Eight months later, Mary and Holcombe were married.

"It was a December wedding," she said, "a beautiful December wedding."

By 1949, two years after Holcombe and Mary wed, Rucker's tournament had moved to the St. Nicholas Houses playground on 128th Street and Seventh Avenue. The park there soon became Rucker's office, a weathered green bench serving as his office chair, an old streetlamp his night-light. There, scores of young black men and women, many from single-parent households, some of whom did not even play basketball, showed up daily for some good, old-fashioned Holcombe advice, finding stability and comfort, guidance and assurance, and ultimately proper direction in their mentor's words.

Harlem's Pied Piper, Rucker spent fourteen and fifteen hours a day in that park. He ate dinner there, his favorite meal a Chinese dish of vegetables and rice with heavy brown gravy. Dessert always came in two courses: a cup of coffee followed by a cigarette. He'd arrive most mornings by 8:30, often finding some kids already waiting for him. For many of them, Rucker's park was a home away from home. "Each one, teach one," was his motto; it would later become the name of a Harlem youth organization run by his disciples.

The Pied Piper imparted his wisdom to talented but underprivileged Harlem hoopsters, hundreds of whom he helped steer off the streets and toward college and a better life. These were kids who perfected their moves on playground courts throughout the city, bringing to the blacktop the grit, muscle, and determination it took to survive on the mean streets where they were raised. That brand of hard-nosed basketball, combined with high-flying, artistic moves to the basket created during years of one-on-one and full-scale battles on the asphalt, became in essence the true identity of the city game, separating it from the way the game was being played in places like Indiana, where country boys were perfecting their long-range shooting in driveways or local gyms, or laid-back California, where the game was becoming associated more with finesse than with the in-your-face attitude found on strips of blacktop throughout New York's five boroughs.

Under the watchful eye of Holcombe Rucker, neighborhood kids honed their considerable skills. Soon, many of these kids began filling the rosters of local college teams, helping schools like New York University, City College, Long Island University (LIU), and St. John's become dominant forces in the early days of college basketball. For some, the basketball ride did not end there, but continued on the professional level in the United States or overseas.

Rucker's young flock, who learned as much about life as basketball from their mentor, included players like Roger Gibbs, who starred at Virginia Union, Ralph "The Durango Kid" Bacote, a sweet-shooting guard who lit it up at Northern Illinois, and Thomas "Satch" Sanders, who teamed with Cal Ramsey at New York University before moving on to win eight championships with the Boston Celtics of Cousy, Russell, and Havlicek.

Catching a Fallen Idol

The gospel according to Holcombe Rucker even saved Ed Warner's life.

After the 1949-50 college basketball season, Ed Warner was on top of the world. The six four forward from Harlem had just led City College to a double championship crown, as City won both the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship. At the time, teams competed in both tournaments, and both were equally important.

Warner, the most valuable player of the NIT that season, and the first black player to receive that award, was rumored to be heading to the mighty Boston Celtics of the NBA.

"Me and every kid in Harlem wanted to be like Ed Warner," said Carl Green, Warner's protege, who had a long career with the Harlem Globetrotters. "Everyone wanted to know him," Green said. "I mean, we played like Ed Warner, we dressed like Ed Warner, and we carried ourselves like Ed Warner."

Green had idolized Warner ever since the day he sat in the old RKO Theater on 116th Street and Seventh Avenue, when a newsreel about City College's powerful hoops program flashed onto the screen.

"That was the year they won both tournaments," said Green, who was fourteen at the time. "I went back to that theater eight times to see that newsreel, and you know, I don't even remember what movie was playing there."

But shortly after City's magical season, the magic carpet ride ended for Warner, as he and six other players from that team--Ed Roman, Alvin Roth, Irwin Dambrot, Norman Mager, Herb Cohen, and Floyd Layne--were arrested and indicted after it was learned that they were also involved in a point-shaving scandal that rocked New York City and the rest of the nation.

Ed Warner never wore Celtic green. He put on a prison uniform instead and spent six months of his life on Rikers Island.

"Me and Floyd were denied access to play in the NBA," said Warner in a rare interview, his last, given a few months before he died in September 2002 at the age of seventy-three. Warner had been confined to a wheelchair in his Harlem apartment, the result of a car accident that nearly took his life on April 23, 1984.

"I was young and foolish at the time," he said, "and when I came home, I found that people were more or less ashamed about what had taken place."

A fallen idol whose ticket to fame was torn by greed and youthful naivete, Warner had few places to turn when he left Rikers for home. Of the thousands of Harlem kids who once looked up to him, few were willing to even give the disgraced star a game of one-on-one.

Ed Warner was now a complete outcast in a world he once conquered. That's when Holcombe Rucker found him.

"Holcombe came to me and said, 'Hey, Ed, I'm not condoning what you fellows did, but I believe that to err is human, to forgive divine.'

"He said, 'I'm gonna give you fellows an opportunity to redeem yourselves.' He was referring to the guys involved in the scandal. I still get goose bumps when I remember him telling me, 'You fellows were young and you didn't know what you were doing. But I'm going to give you an opportunity to come back to your community and let the people know that you made a mistake as a youngster and you tried very hard to correct the mistakes that you made. I'm forming this tournament, and I'd like very much for you to be a part of it.'

From the Hardcover edition.

THE PIED PIPER

On March 2, 1926, Holcombe Rucker came into a hard life. He was raised in poverty by his grandmother, Rosa Deniston, who struggled to make the rent at 141st Street and Bradhurst Avenue. He was a star guard at Benjamin Franklin High School in East Harlem, but dropped out to go off to serve in the United States Army during World War II. By the time Uncle Sam sent him home in 1946, he was a mature and extremely focused young man.

That year, Rucker came back to Harlem and earned a general equivalency high school diploma, then enrolled at CCNY, where he took night classes and needed just three years to complete a four-year bachelor of arts degree. He landed a job as a recreational director with the New York City Department of Parks; taught English at Harlem's Junior High School 139, and worked at St. Phillips, a local parish church and community center at 134th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, where he served as a basketball coach and created a basketball tournament that featured divisions made up of various age groups. The purpose of the tournament was to keep neighborhood kids off the streets and out of trouble. Through lessons learned in the discipline and dedication it took to become a winning basketball team, Rucker was able to teach his players a lot about life. Most of these players were living in poverty as well, and Rucker wanted them to make something of themselves so that they could avoid the kind of hard life he had known as a child.

Charles Turner, a Rucker disciple, played for Holcombe Rucker at St. Phillips. "I played for the Mites," Turner said, "before I graduated to the Midgets."

Turner is sixty-five now, but he "can remember like yesterday" the day his life was turned around by Rucker at halftime of a weekend game between St. Phillips and a powerhouse team from Harlem's YMCA.

At the time, Turner was a fourteen-year-old hotshot from Central Needle Trade High School with a lot of attitude but not much discipline.

"We went out on the court that day and just started clowning around, trying to make fancy passes and just do our own thing," Turner said. "We were just kids, I guess, just having fun."

At halftime, St. Phillips trailed the YMCA by 30 points. Holcombe Rucker, not smiling on this day, sat his team down in the locker room. He hesitated a moment before he spoke, his gentle eyes sweeping over every one of them. And then he let loose.

"I put all of this training into every one of you, all of this time!" Rucker shrieked. "And you're out there bullshitting?"

Rucker paused again, burning a look into his players. As he stared long and hard, tears began to stream down his cheeks.

"We were frozen scared," Turner said. "We were all tough kids from the streets. We had never seen a grown man cry before."

Rucker never said another word.

"He didn't have to," Turner said. "It was a lesson in discipline and respect that we would never forget."

Turner and his teammates went out and completely dominated the second half, grabbing every rebound, hustling for every loose ball.

"Those kids from the Y were looking at us like we were possessed or something," Turner said. "We ended up winning that game by 30 points."

Charles Turner still lives in Harlem, and so too does the memory of Holcombe Rucker, who left New York City a basketball treasure that still bears his name. The legacy of Turner's mentor is everywhere. It lives in Harlem classrooms and barrooms, in gymnasiums and living rooms, and it was alive and well one frigid day at Charles Restaurant in Harlem, just a bounce pass from Rucker Park, where Turner and Ernie Morris, a Rucker historian, were wearing sour faces over their sweet yams.

"Earl Manigault needed to be smacked, literally smacked to degrade Rucker like that," said the fifty-nine-year-old Morris, spearing his ham hocks as he spoke. "I mean, Rucker wasn't a fat guy who earned a living cleaning parks, the man was a Parks Department director who helped thousands of us Harlem kids go to college, and kept thousands more off the streets and out of jail."

On a winter's day in the basketball capital of the universe, a hot lunch is spoiled when Turner brings up the movie Rebound: The Legend of Earl "The Goat" Manigault, which was broadcast with a great deal of fanfare on HBO.

Don Cheadle plays the Goat, a high-flying dunking machine with a heroin problem who gets swallowed up by the same mean streets he once soared over (we'll hear a great deal about him in the chapters to follow). Forest Whitaker plays Holcombe Rucker, who speaks words of wisdom while standing behind a garbage pail, a broom, and a big belly.

"Earl was a consultant on the set," says Turner. "I liked the Goat a whole lot, but why did he have to describe Mr. Rucker like that to those movie people? It just didn't make any sense."

Perhaps no one knew Holcombe Rucker, the man, better than Morris and Turner, both high school hoop stars from the 1950s who learned their games under him at St. Phillips. According to them, Rucker was all about one thing, helping kids, especially troubled kids. He was not, they insist, "some fool Parks Department custodian" they had read about throughout the years in newspapers and magazines or seen portrayed on television.

"When you played ball for him, you learned to answer every one of his questions with a 'yes sir,' or a 'no sir,' " Turner said. "And don't even think about playing ball unless Mr. Rucker took a look at your report card and approved of it."

In the summer of 1946, Rucker began staging an outdoor tournament on 138th Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenues. Those early outdoor tourneys opened with four teams and one referee, Rucker himself.

In time, Rucker's vision expanded, and he began scheduling games for his playground teams against other youth organizations throughout New York City. Those who knew Rucker well say he managed his youth leagues despite a lack of cooperation from the Department of Parks, which turned its back on him. There were times, friends say, when Rucker would have to scrape up loose change to buy a whistle, and others when he had to borrow basketballs from some of the kids playing in his games.

The late John "Twenty Grand" Hunter, a dapper "street entrepreneur with his ear to the street" as one player from those days describes him, often slipped Rucker a few dollars when the going got real tight. Though Hunter earned much of his money through sports gambling on events like horse racing and football games, he was always generous with his profits where Holcombe Rucker was concerned. If Rucker's kids needed uniforms or sneakers and couldn't afford them, Hunter went deep into his pockets. Hunter also provided transportation money for players traveling to and from games, and he made sure that every car or bus that transported the players had a full tank of gas.

Ernie Morris remembers playing on those early Rucker teams, and competing against the very best that the city had to offer: "Hook or crook, Holcombe had us on the move," he said. "We played against black kids from the Bronx, Irish and Italian kids from Hell's Kitchen, anyone who wanted to give us a game."

A Date with Mary

Holcombe Rucker's hoop dream was slowly coming into focus on an April night in 1947, when a friend asked if he would do him a favor and take his date, a young woman named Mary Green, to a Billie Holiday performance at Small's Paradise Club on 135th Street and Seventh Avenue. Rucker's friend had made other plans that evening, and though he and Mary were not seriously involved, he did not want to hurt her feelings.

"But I have my own date tonight," Holcombe told his friend.

"Please," Holcombe's friend replied. "Just do me this favor, just this once."

So Holcombe took Mary to Small's, which ranked in Harlem and show business legends with the old Cotton Club and the Savoy Ballroom. It was the place where Harlem's elite gathered for good times when talents like Holiday, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Billy Eckstine, Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Bill Robinson dominated the stage.

"Holcombe had a date and told her to meet him there," Mary Rucker Thomas recently recalled. "But when his girlfriend came in, I guess she saw us together, and she just went and sat somewhere else."

And Mary's original date?

"He just never showed up, and Holcombe knew he wasn't going to," she recalled. "So Holcombe just stayed there with me and we listened to Billie Holiday together. I thought to myself, 'Here's a real nice guy.' "

Eight months later, Mary and Holcombe were married.

"It was a December wedding," she said, "a beautiful December wedding."

By 1949, two years after Holcombe and Mary wed, Rucker's tournament had moved to the St. Nicholas Houses playground on 128th Street and Seventh Avenue. The park there soon became Rucker's office, a weathered green bench serving as his office chair, an old streetlamp his night-light. There, scores of young black men and women, many from single-parent households, some of whom did not even play basketball, showed up daily for some good, old-fashioned Holcombe advice, finding stability and comfort, guidance and assurance, and ultimately proper direction in their mentor's words.

Harlem's Pied Piper, Rucker spent fourteen and fifteen hours a day in that park. He ate dinner there, his favorite meal a Chinese dish of vegetables and rice with heavy brown gravy. Dessert always came in two courses: a cup of coffee followed by a cigarette. He'd arrive most mornings by 8:30, often finding some kids already waiting for him. For many of them, Rucker's park was a home away from home. "Each one, teach one," was his motto; it would later become the name of a Harlem youth organization run by his disciples.

The Pied Piper imparted his wisdom to talented but underprivileged Harlem hoopsters, hundreds of whom he helped steer off the streets and toward college and a better life. These were kids who perfected their moves on playground courts throughout the city, bringing to the blacktop the grit, muscle, and determination it took to survive on the mean streets where they were raised. That brand of hard-nosed basketball, combined with high-flying, artistic moves to the basket created during years of one-on-one and full-scale battles on the asphalt, became in essence the true identity of the city game, separating it from the way the game was being played in places like Indiana, where country boys were perfecting their long-range shooting in driveways or local gyms, or laid-back California, where the game was becoming associated more with finesse than with the in-your-face attitude found on strips of blacktop throughout New York's five boroughs.

Under the watchful eye of Holcombe Rucker, neighborhood kids honed their considerable skills. Soon, many of these kids began filling the rosters of local college teams, helping schools like New York University, City College, Long Island University (LIU), and St. John's become dominant forces in the early days of college basketball. For some, the basketball ride did not end there, but continued on the professional level in the United States or overseas.

Rucker's young flock, who learned as much about life as basketball from their mentor, included players like Roger Gibbs, who starred at Virginia Union, Ralph "The Durango Kid" Bacote, a sweet-shooting guard who lit it up at Northern Illinois, and Thomas "Satch" Sanders, who teamed with Cal Ramsey at New York University before moving on to win eight championships with the Boston Celtics of Cousy, Russell, and Havlicek.

Catching a Fallen Idol

The gospel according to Holcombe Rucker even saved Ed Warner's life.

After the 1949-50 college basketball season, Ed Warner was on top of the world. The six four forward from Harlem had just led City College to a double championship crown, as City won both the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship. At the time, teams competed in both tournaments, and both were equally important.

Warner, the most valuable player of the NIT that season, and the first black player to receive that award, was rumored to be heading to the mighty Boston Celtics of the NBA.

"Me and every kid in Harlem wanted to be like Ed Warner," said Carl Green, Warner's protege, who had a long career with the Harlem Globetrotters. "Everyone wanted to know him," Green said. "I mean, we played like Ed Warner, we dressed like Ed Warner, and we carried ourselves like Ed Warner."

Green had idolized Warner ever since the day he sat in the old RKO Theater on 116th Street and Seventh Avenue, when a newsreel about City College's powerful hoops program flashed onto the screen.

"That was the year they won both tournaments," said Green, who was fourteen at the time. "I went back to that theater eight times to see that newsreel, and you know, I don't even remember what movie was playing there."

But shortly after City's magical season, the magic carpet ride ended for Warner, as he and six other players from that team--Ed Roman, Alvin Roth, Irwin Dambrot, Norman Mager, Herb Cohen, and Floyd Layne--were arrested and indicted after it was learned that they were also involved in a point-shaving scandal that rocked New York City and the rest of the nation.

Ed Warner never wore Celtic green. He put on a prison uniform instead and spent six months of his life on Rikers Island.

"Me and Floyd were denied access to play in the NBA," said Warner in a rare interview, his last, given a few months before he died in September 2002 at the age of seventy-three. Warner had been confined to a wheelchair in his Harlem apartment, the result of a car accident that nearly took his life on April 23, 1984.

"I was young and foolish at the time," he said, "and when I came home, I found that people were more or less ashamed about what had taken place."

A fallen idol whose ticket to fame was torn by greed and youthful naivete, Warner had few places to turn when he left Rikers for home. Of the thousands of Harlem kids who once looked up to him, few were willing to even give the disgraced star a game of one-on-one.

Ed Warner was now a complete outcast in a world he once conquered. That's when Holcombe Rucker found him.

"Holcombe came to me and said, 'Hey, Ed, I'm not condoning what you fellows did, but I believe that to err is human, to forgive divine.'

"He said, 'I'm gonna give you fellows an opportunity to redeem yourselves.' He was referring to the guys involved in the scandal. I still get goose bumps when I remember him telling me, 'You fellows were young and you didn't know what you were doing. But I'm going to give you an opportunity to come back to your community and let the people know that you made a mistake as a youngster and you tried very hard to correct the mistakes that you made. I'm forming this tournament, and I'd like very much for you to be a part of it.'

From the Hardcover edition.