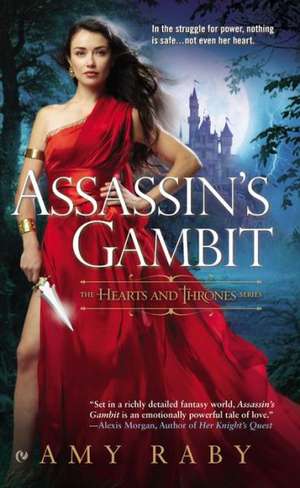

Assassin's Gambit: The Hearts and Thrones: The Hearts and Thrones Series

Autor Amy Rabyen Limba Engleză Paperback – apr 2013 – vârsta de la 18 ani

Vitala Salonius, champion of the warlike game of Caturanga, is as deadly as she is beautiful. She’s a trained assassin for the resistance, and her true play is for ultimate power. Using her charm and wit, she plans to seduce her way into the emperor’s bed and deal him one final, fatal blow, sparking a battle of succession that could change the face of the empire.

As the ruler of a country on the brink of war and the son of a deposed emperor, Lucien must constantly be wary of an attempt on his life. But he’s drawn to the stunning Caturanga player visiting the palace. Vitala may be able to distract him from his woes for a while—and fulfill other needs, as well.

Lucien’s quick mind and considerable skills awaken unexpected desires in Vitala, weakening her resolve to finish her mission. An assassin cannot fall for her prey, but Vitala’s gut is telling her to protect this sexy, sensitive man. Now she must decide where her heart and loyalties lie and navigate the dangerous war of politics before her gambit causes her to lose both Lucien and her heart for good.…

Preț: 46.52 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.91€ • 9.16$ • 7.39£

8.91€ • 9.16$ • 7.39£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780451417824

ISBN-10: 0451417828

Pagini: 389

Dimensiuni: 114 x 188 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Signet Book

Seria The Hearts and Thrones Series

ISBN-10: 0451417828

Pagini: 389

Dimensiuni: 114 x 188 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Signet Book

Seria The Hearts and Thrones Series

Recenzii

“Set in a richly detailed fantasy world, Assassin’s Gambit is an emotionally powerful tale of love.”—Alexis Morgan, author of Her Knight’s Quest

Notă biografică

Amy Raby is literally a product of the U.S. space program, since her parents met working for NASA on the Apollo missions. After earning her bachelor's in Computer Science from the University of Washington, Amy settled in the Pacific Northwest with her family, where she's always looking for life's next adventure, whether it's capsizing tiny sailboats in Lake Washington or riding dressage horses. Amy is a 2011 Golden Heart® finalist and a 2012 Daphne du Maurier winner. Assassin's Gambit is her debut novel.

Extras

Chapter 1

“Vitala Salonius?”

She set down her heavy valise on the dock’s oak planking. The man approaching her looked the quintessential Kjallan—tall and muscular, black hair, and a hawk nose. He wore Kjallan military garb, double belted, with a sword on one hip. On the other hip sat a flintlock pistol with a walnut stock and gilt bronze mounts, so fine and polished that Vitala found herself coveting it. His orange uniform bore no blood mark but instead the sickle and sunburst—the insignia of the Legaciatti, which made him one of the emperor’s famed personal bodyguards.

“Yes, sir. That’s me,” she said.

His handsome face broke into a smile. “My name is Remus, and I’m here to escort you to the palace. I’ll get that for you.” He hefted the valise with ease and gestured at a carriage waiting at the end of the dock.

She followed him, swaying at the sensation of being on dry land after two weeks aboard ship. Remus’s riftstone was not visible. Most Kjallan mages wore them on chains around their necks, concealed beneath their clothes. The collar of Remus’s uniform hid even the chain. He was certainly a mage—all the Legaciatti were—but she could not tell what sort of magic he possessed. Was he a war mage? That was the only type difficult to kill. She relaxed her mind a little, opening herself to the tiny fault lines that separated her world from the spirit world, and viewed the ghostly blue threading of his wards. He was well protected from disease, parasites, and even from the conception of a child.

They arrived at the carriage, a landau pulled by dark bays. At Remus’s gesture, she climbed inside. He handed her valise to a bespectacled footman, who heaved it onto the back and strapped it in place. Remus, whom she’d expected to ride on the back or up front with the driver, stepped into the carriage and sat in the seat opposite her. Of course. The vetting process began here. He would make small talk, and she’d have to be very, very careful what she said to him.

The carriage lurched forward, and the Imperial City of Riat began to pass by the windows—wide streets and narrow ones, large homes and small ones, with the usual collection of inns, shops, and street vendors crammed into the available spaces. She spotted a millinery shop, a gunsmith, a Warder’s, an open-air market with fresh, imported lemons. A newsboy with an armload of papers cried his wares from a corner. Kjallan townsfolk moved about the streets, buying, flirting, and trading gossip. The citizens caught her eye with their brightly colored, robelike syrtoses, while slaves in gray flitted by like shadows. The city was pleasant enough, but unremarkable. Well, what had she expected? Marble houses? Streets lined with diamonds?

“I hear you’re a master of Caturanga,” said Remus.

“Yes, sir. I won the tournament this year in Beryl.”

“The emperor was impressed by your accomplishment.” His blue eyes studied her with a more than casual interest.

“I’m honored by that.”

“And you’re from the province of Dahat?”

Please don’t be from Dahat yourself. It would be a disaster if he were looking for someone to swap childhood stories with. She’d been to Dahat, so she could provide a few details about the region, but she hadn’t grown up there. “Yes, sir.”

“How are feelings toward the emperor there?”

Her forehead wrinkled. What sort of question is that? “Citizens of Dahat have great respect for Emperor Lucien.”

Remus laughed. “You think this is a loyalty test, don’t you? Tell me the truth, Miss Salonius. Emperor Lucien likes to know how public sentiment runs throughout his empire. Platitudes and blind expressions of loyalty mean nothing to him. He wants honesty.”

Vitala bit her lip. “I’ve been on the Caturanga circuit for more than three years, sir, longer than Emperor Lucien’s reign. What little I picked up from my visits home is that while most of the citizenry supports him, there are some who disapprove of his policies and preferred the former emperor. I imagine that would be true in any province.”

“Indeed,” said Remus. “There are those who miss the old Emperor Florian and his Imperial Garden. Have you had the privilege of visiting it?”

“Visiting what?”

“Florian’s Imperial Garden.”

“No, sir. This is my first visit to the palace.” Vitala was puzzled. He had to know that already.

“Ah,” he said. “You should seek it out during your visit.”

“That would be lovely, sir.”

The carriage tilted backward. Vitala looked out her window. They’d passed through the city and started up the steep hill that led to the Imperial Palace. The carriage was navigating the first of half a dozen switchbacks. When she turned back to Remus, his eyes had lost their intensity. Whatever the test was, it seemed she’d passed it. “You are the first woman to win the Beryl tournament,” he said. “Pray tell me who you studied under.”

Vitala smiled. This was one of the questions she’d been coached on. “My father taught me to play when I was four years old and I showed an aptitude for the game. Within a year, I could beat my cousins. Later, I studied under Caecus, and when I’d mastered his teachings, I studied under Ralla.” She droned on, feeding him the lies she’d recited under Bayard’s tutelage. Remus leaned back and nodded dully. It seemed he’d lost interest in her. Thank the gods.

As the carriage crested the final switchback, Vitala craned her neck for a look at the Imperial Palace. Three white marble domes, each topped with a gilt roof, rose into view, gleaming in the sunshine. Next appeared the numerous outbuildings and walled gardens that surrounded the domes. A wide, tree-lined avenue directed them to the front gates.

Inside the palace, silk hangings of immeasurable value draped the walls, while priceless paintings and sculptures graced every nook. She’d never been anywhere so boldly ostentatious. What a contrast to Riorca, with its broken streets and ramshackle pit houses! How much of this had been built by Riorcan slave labor?

Two Legaciatti, both women, met them inside the door. Vitala studied them, curious at the oddity of female Kjallan soldiers. Bayard had told her that women made ideal assassins for Kjallan targets because Kjallan men didn’t take women seriously. Ostensibly, that was true; Kjall was patriarchal, and women had little power under the law. But as she’d traveled on the tournament circuit, she’d learned the reality was more complicated. Most Kjallan men were soldiers who were often away from home. In their absence, their wives had authority over their households. Women and slaves were the real engine of Kjall’s economy; few men had many practical skills outside of soldiering.

“Search her,” ordered Remus.

One of the women beckoned. “Come along.”

The search took place in a private room and was humiliatingly thorough. Vitala knew what they were looking for: concealed weapons or perhaps a riftstone. They would not find either. She didn’t wear her riftstone around her neck; it was surgically implanted in her body, along with the deathstone, her escape from torture and interrogation if she botched this mission. Her weapons were magically hidden where none but a wardbreaker could detect them. And there were no Kjallan wardbreakers; only Riorcans possessed the secrets of that form of magic.

As she put her clothes back on, the Legaciatti emptied her valise, checked it for hidden compartments, and pawed through her paltry collection of spare clothes, undergarments, powders, and baubles. They found nothing that concerned them.

They repacked her things and led her up two flights of white marble stairs. The walls were rounded and concave; she must be in one of the domes. Her room was the third on the right from the top of the stairway. A young guard with peach fuzz on his chin stood in front of it, wearing an orange uniform but no sickle and sunburst. Peach fuzz. He looked familiar.

The young soldier lay on the cot, his wrists and ankles bound. His blanket had fallen to the floor, a result of his struggles. His eyes jerked toward her, wide with fear, but when he saw her, he relaxed a little. He wasn’t expecting a teenage girl.

“Miss Salonius?”

He shouldn’t know her name. How did he know her name?

“Miss Salonius?”

And why did he sound like a woman?

Vitala blinked. The Legaciatti were staring at her in concern. “Miss Salonius?” one of them asked.

“I’m sorry.” Gods, where was she? Marble walls. The Imperial Palace.

“You stopped moving. You were staring into space.”

“Sorry, I was . . . never mind.” Averting her eyes so that she wouldn’t see the young man guarding her door, she stepped inside.

Vitala’s room was a suite. Just inside was a sitting room with a single peaked window along its curved wall and a pair of light-glows in brass mountings suspended from the ceiling. The room was lavishly furnished with carved oaken tables and chairs upholstered in silk. A bookshelf on the far wall drew her eye. Among its contents, she recognized all the classic treatises on Caturanga and some she’d never seen before, as well as books on other subjects. An herbal by Lentulus. Cinna’s Tactics of War. Numerous works of fiction, including the notoriously racy Seventh Life of the Potter’s Daughter. Who had put that a book like that into an otherwise erudite bookshelf?

On a table in the center of the room sat the finest Caturanga set she’d ever seen. Pieces of carved agate with jeweled eyes winked at her from a round, two-tiered board of polished marble. She picked up one of the red cavalry pieces. The rider was richly detailed down to the folds of his cloak. The warhorse was wild-eyed, his beautifully carved expression showing equal parts fear and determination.

Had Emperor Lucien set up this room just for her? No, of course not. He hosted many Caturanga champions. Probably all of them had been housed here.

The bedroom was equally fine, with a high, four-poster bed, silk sheets, and a damask down-stuffed comforter. The silk hangings were blue and red. Was that by design? Blue and red were the traditional colors of Caturanga pieces.

“You will reside here until the emperor summons you,” a Legaciatta instructed. “Take your rest as needed, but you are not to wander about the palace. If you desire something, such as food or drink, ask the door guard. If you wish to bathe, he can escort you to the baths on the lower level.”

Vitala nodded. “Thank you, ma’am.”

The Legaciatti left, closing the door behind them. Vitala went to the window—real glass, she noted—and peered out. Below was a walled enclosure obscured by a canopy of trees, through which she caught glimpses of red, purple, and orange. The famous Imperial Garden? Looking up to take in the broader view, she noticed a patch of too-light blue in the sky and picked out the Vagabond, the tiny moon that glowed blue at night but faded almost to invisibility in the daytime. God of reversals and unforeseen disaster, the Vagabond wandered across the sky in the direction opposite the other two moons, and was not always a favorable sighting. “Great One, pass me by,” she prayed reflexively.

Leaving the window and lighting one of the glows with a touch of her finger, she pulled Seventh Life from the bookshelf. Sprawling on a couch, she waited upon the pleasure of the emperor.

Vitala was not her given name. When she was born dark-haired, Papa named her Kolta: “blackbird.”

She was eight years old when the stranger arrived. Mama and Papa took him into the bedroom to speak with him. They shut her out, but she pressed her ear against the door to listen.

“We’ve completed the testing,” said the stranger, “and your daughter is exactly what we’re looking for. Highly intelligent, physically strong, and coordinated. And, of course, she’s black-haired.”

Mama said something she couldn’t quite make out.

“In the village, perhaps,” replied the stranger. “But in the Circle, dark hair is an asset. She can pass for Kjallan. It will allow her to move in areas where others cannot.”

More mumbling from Mama.

“The Circle is prepared to offer you compensation. Four hundred tetrals.”

Papa gasped.

Mama raised her voice. “I’m not selling my daughter!”

“Of course not,” soothed the stranger. “But Kolta will never reach her potential here in the village—not with the prejudice against girls like her. Why subject her to harassment and ostracism, when among the Circle she will be valued and revered? The money is our gift to you. A token of our thanks for aiding Riorca in its time of need.”

Mama began to sob.

“Treva, he’s right,” said Papa. “It would be selfish to keep Kolta here. A half-Kjallan bastard will never be accepted—”

“You hate her!” cried Mama. “You want to be rid of her!”

“Madam,” said the stranger, “consider the advantages to Kolta in joining the Circle. She will receive a thorough education, far better than anything she could get here. And she will be among her own kind. We have other half-breeds like her, dark-haired girls who know what it’s like to be Riorcan but look Kjallan. For the first time in her life, she will have friends.”

Mama continued to sob.

“Treva, think of it,” said Papa. “Four hundred tetrals! You know what that money would mean for us. This man is right. The Circle can do far better for Kolta than we can.”

Something unintelligible from Mama.

“No,” said the stranger. “It must be now. She must begin her language training immediately, or she’ll never speak with the proper accent.”

A long silence followed, broken only by Mama’s sobbing. There were soft words that Kolta could not make out.

The stranger was saying, “We find it’s best if there are no good-byes.”

The door opened, and the stranger stepped out. Terrified, Kolta hid in the corner between the wall and the door. But the door moved away, revealing her. The stranger stared down at her in surprise. “Were you listening, Kolta?”

She shook her head.

He knelt, bringing himself to her eye level. “Tell me the truth, and you will not be in trouble. Were you listening?”

She hesitated a moment, but nodded.

“And yet you do not cry.” His mouth twisted as he lifted her chin with his finger. “My name is Bayard. I’m going to be your friend, Kolta. Would you like that?”

She was silent.

“The people here don’t treat you very well, do they? They don’t like dark-haired girls. But I’m going to take you somewhere else. Somewhere you’ll be loved, Kolta. Do you want to be loved?”

Her chin began to tremble.

“Of course you do.” He folded her into his arms, and she began to cry. “It’s what we all want.”

Lucien limped on his artificial leg his way through the doorway into his office, fell into his chair, and leaned his crutch against the wall. Three years he’d been emperor, and still a shiver went down his spine every time he crossed that threshold. He’d spent too much time in the opposite chair, the one on the other side of the desk, facing a loud and frightening father he could never please.

Septian, his bodyguard, a head taller than Lucien and twice as broad, moved in almost perfect silence as he took his customary place behind the chair and shouldered a musket. He carried the weapon more for show than for any real need; it would be a rare enemy Septian couldn’t handle with a sword or a knife or even his bare hands. Lucien had been escorted by Legaciatti all his life, but since ascending the throne, he’d become hyperaware of them, especially Septian. The man rarely spoke, and his face was impossible to read. What did he think of Lucien? Did he recognize Lucien’s head for military strategy? Or, like Florian, did he privately roll his eyes at what he perceived as a useless, crippled boy?

Lucien rubbed his forehead. His empire was fragile, precarious. He had problems to solve. Real problems. What his bodyguards thought of him should be the least of his concerns.

Septian cleared his throat.

Lucien raised his head and saw the man standing in the doorway. “Remus. Come.”

The Legaciattus entered, bowed his obeisance, and sat in the chair across from him. The door guards shut him in.

“What’s the schedule today?” asked Lucien.

“You’re seeing Legatus Cassian Nikolaos this morning.”

Lucien made a face. “Pox. Is he waiting outside?”

“Yes, sir. And this afternoon, you were going to speak to the new recruits at the palaestra. Then there’s the meetings with your advisors.”

Lucien nodded. The morning would be a harassment, but the afternoon wasn’t so bad. He liked public speaking, especially when the audience was young soldiers—it wasn’t long since he’d been one himself. He’d seen action on the battlefield, and frontline soldiers tended to respect that.

Was there a gap in his schedule? His meeting with Cassian would not take all morning. “Remus, has that woman who won in Beryl arrived yet?”

Remus smiled. “She arrived by ship yesterday, Your Imperial Majesty, and awaits your pleasure.”

Lucien brightened. “Have her ready to play by midmorning.”

“Very good, Your Imperial Majesty. Shall I send in Cassian?”

“Yes.”

Remus left, and the guards admitted Legatus Cassian Nikolaos, Lucien’s highest-ranking military officer. Cassian was a longtime friend of Lucien’s father, the former emperor, and he was everything Lucien wasn’t. Big, burly, whole—that is, possessed of all four limbs—and afraid of nothing. Middle-aged, he had decades of command experience behind him, and it rankled him to report to an emperor in his twenties. “Legatus,” said Lucien, granting the man permission to speak.

“Your Imperial Majesty.” Cassian bowed.

Lucien’s eyes narrowed. The bow wasn’t as low as it ought to be. It bordered on insolence, yet the slight was subtle. He would look foolish if he drew attention to it. “Have a seat.” He’d tried several strategies for winning Cassian’s respect. Flattery hadn’t worked. Neither had pointing out the patently obvious holes in the man’s proposed strategies. In the end, he’d given up and fallen back on the style he’d used with his equally intractable father, a tone of breezy, uncaring confidence. It didn’t work either.

Cassian began, “Lucien, about the Riorcan rebels—”

“That’s Sir or Your Imperial Majesty,” snapped Lucien. “And I’m not going to decimate the Riorcans.”

Cassian stiffened. “Sir, you’ve let their crimes go unpunished far too long. They flaunt their disrespect in a hundred tiny ways every day, and their Obsidian Circle sabotages our supply lines and assassinates our officers.”

“I have a battalion combing the hills in search of the Circle. It’s not easy to find. In the past year, we’ve found only two enclaves, neither of which had more than twenty people in it. And you know what my soldiers discovered when they broke in.”

“Corpses,” said Cassian.

“They killed themselves rather than risk interrogation. We know nothing about where their headquarters are or who’s in charge.”

“Sir, this is why you have to decimate the Riorcan villages. We can’t find the Circle, but we can find the villagers who support them. Punish them, and that support will end.”

“Cassian.” Lucien paused, considering his words carefully. “You are one of Kjall’s finest commanders, and I have a tremendous respect for your experience in the field. But you haven’t been in Riorca. I have—”

“For two years!” spat Cassian.

“Two years longer than you have, and those years opened my eyes. Most Riorcans want nothing more than to live their lives and raise their families in peace. The rebels are a minority. Your opinion is noted, but my mind is made up. We will not decimate Riorca.”

“Yes, sir.” Instead of leaving, Cassian sat quietly in his chair.

Lucien eyed him narrowly. “You are dismissed, Legatus.”

“Sir, about last night’s state dinner . . .” He hesitated.

“Didn’t like my speech?”

“Your oration was superlative and the food exquisite. But you deprived us of the court’s brightest jewel, the imperial princess.”

Lucien’s mouth tightened. “Celeste chose not to attend.”

“At your urging, no doubt.”

“She is thirteen years old, Legatus, and she finds state dinners tedious.” Indeed, he could hardly blame his sister for not wanting to spend an evening being slobbered over by older men looking to insert themselves into the line of succession. In Cassian’s case, it was particularly disgusting, because he was already married. He would divorce his wife in a heartbeat if he thought he could remarry more advantageously. And while politically motivated divorces and marriages were common in Kjall, Lucien considered the practice repugnant.

“Perhaps she found them dull when she was a child, but she’s a young woman now. Young women love to be the center of attention. Perhaps she would like to attend the upcoming dinner for the Asclepian delegates? I should be glad to escort her.”

Lucien stared at him stonily. “No.”

“If you should change your mind—” began Cassian.

“You are dismissed, Legatus.”

Vitala paced nervously in her suite. The door guard—a new one, thank the gods; there must have been a shift change—had informed her the emperor would see her later that morning. Soon, the moment would come, the moment she’d spent eleven years preparing for. Could she seduce and kill Emperor Lucien?

Seduction was the easy part, but she’d never targeted an emperor before.

We know very little about his love life, Bayard had told her. Only that he must have one.

What if he liked only blondes or redheads? Gods, what if he preferred men?

She’d suggested to Bayard that she lose her first Caturanga game with Lucien. She’d seduced a Kjallan officer once with a similar technique. She played the part of a foolish bufflehead searching for a misplaced glove, which turned out to be under her chair. A little flattery and flirtation, a touch here and there, and he was hers. But soldiers were easy; an emperor was something else. Lucien was probably approached by beautiful, sexually receptive women on a daily basis. She had to make herself stand out.

You must win the initial game, Bayard had said. He may lose interest if he thinks you have nothing to teach him. And we don’t know how long it will take you to lure him into bed. This man is powerful. He has his choice of women. And he may be particular.

Thanks for the encouragement, she had retorted.

We suspect he likes strong women.

How can you tell, if you know nothing about his love life? she asked.

Because the closest relationship he’s ever had with a woman was with his cousin Rhianne, said Bayard.

The one who ran off to Mosar?

She was rebellious as a child, and Lucien was her partner in crime. Word is he misses her. We think the more you remind him of Rhianne, the more interested in you he’ll be.

Fine. She would win the first game. But how to proceed from there?

Someone knocked at her door. “Miss Vitala? His Imperial Majesty will see you now.”

“Vitala Salonius?”

She set down her heavy valise on the dock’s oak planking. The man approaching her looked the quintessential Kjallan—tall and muscular, black hair, and a hawk nose. He wore Kjallan military garb, double belted, with a sword on one hip. On the other hip sat a flintlock pistol with a walnut stock and gilt bronze mounts, so fine and polished that Vitala found herself coveting it. His orange uniform bore no blood mark but instead the sickle and sunburst—the insignia of the Legaciatti, which made him one of the emperor’s famed personal bodyguards.

“Yes, sir. That’s me,” she said.

His handsome face broke into a smile. “My name is Remus, and I’m here to escort you to the palace. I’ll get that for you.” He hefted the valise with ease and gestured at a carriage waiting at the end of the dock.

She followed him, swaying at the sensation of being on dry land after two weeks aboard ship. Remus’s riftstone was not visible. Most Kjallan mages wore them on chains around their necks, concealed beneath their clothes. The collar of Remus’s uniform hid even the chain. He was certainly a mage—all the Legaciatti were—but she could not tell what sort of magic he possessed. Was he a war mage? That was the only type difficult to kill. She relaxed her mind a little, opening herself to the tiny fault lines that separated her world from the spirit world, and viewed the ghostly blue threading of his wards. He was well protected from disease, parasites, and even from the conception of a child.

They arrived at the carriage, a landau pulled by dark bays. At Remus’s gesture, she climbed inside. He handed her valise to a bespectacled footman, who heaved it onto the back and strapped it in place. Remus, whom she’d expected to ride on the back or up front with the driver, stepped into the carriage and sat in the seat opposite her. Of course. The vetting process began here. He would make small talk, and she’d have to be very, very careful what she said to him.

The carriage lurched forward, and the Imperial City of Riat began to pass by the windows—wide streets and narrow ones, large homes and small ones, with the usual collection of inns, shops, and street vendors crammed into the available spaces. She spotted a millinery shop, a gunsmith, a Warder’s, an open-air market with fresh, imported lemons. A newsboy with an armload of papers cried his wares from a corner. Kjallan townsfolk moved about the streets, buying, flirting, and trading gossip. The citizens caught her eye with their brightly colored, robelike syrtoses, while slaves in gray flitted by like shadows. The city was pleasant enough, but unremarkable. Well, what had she expected? Marble houses? Streets lined with diamonds?

“I hear you’re a master of Caturanga,” said Remus.

“Yes, sir. I won the tournament this year in Beryl.”

“The emperor was impressed by your accomplishment.” His blue eyes studied her with a more than casual interest.

“I’m honored by that.”

“And you’re from the province of Dahat?”

Please don’t be from Dahat yourself. It would be a disaster if he were looking for someone to swap childhood stories with. She’d been to Dahat, so she could provide a few details about the region, but she hadn’t grown up there. “Yes, sir.”

“How are feelings toward the emperor there?”

Her forehead wrinkled. What sort of question is that? “Citizens of Dahat have great respect for Emperor Lucien.”

Remus laughed. “You think this is a loyalty test, don’t you? Tell me the truth, Miss Salonius. Emperor Lucien likes to know how public sentiment runs throughout his empire. Platitudes and blind expressions of loyalty mean nothing to him. He wants honesty.”

Vitala bit her lip. “I’ve been on the Caturanga circuit for more than three years, sir, longer than Emperor Lucien’s reign. What little I picked up from my visits home is that while most of the citizenry supports him, there are some who disapprove of his policies and preferred the former emperor. I imagine that would be true in any province.”

“Indeed,” said Remus. “There are those who miss the old Emperor Florian and his Imperial Garden. Have you had the privilege of visiting it?”

“Visiting what?”

“Florian’s Imperial Garden.”

“No, sir. This is my first visit to the palace.” Vitala was puzzled. He had to know that already.

“Ah,” he said. “You should seek it out during your visit.”

“That would be lovely, sir.”

The carriage tilted backward. Vitala looked out her window. They’d passed through the city and started up the steep hill that led to the Imperial Palace. The carriage was navigating the first of half a dozen switchbacks. When she turned back to Remus, his eyes had lost their intensity. Whatever the test was, it seemed she’d passed it. “You are the first woman to win the Beryl tournament,” he said. “Pray tell me who you studied under.”

Vitala smiled. This was one of the questions she’d been coached on. “My father taught me to play when I was four years old and I showed an aptitude for the game. Within a year, I could beat my cousins. Later, I studied under Caecus, and when I’d mastered his teachings, I studied under Ralla.” She droned on, feeding him the lies she’d recited under Bayard’s tutelage. Remus leaned back and nodded dully. It seemed he’d lost interest in her. Thank the gods.

As the carriage crested the final switchback, Vitala craned her neck for a look at the Imperial Palace. Three white marble domes, each topped with a gilt roof, rose into view, gleaming in the sunshine. Next appeared the numerous outbuildings and walled gardens that surrounded the domes. A wide, tree-lined avenue directed them to the front gates.

Inside the palace, silk hangings of immeasurable value draped the walls, while priceless paintings and sculptures graced every nook. She’d never been anywhere so boldly ostentatious. What a contrast to Riorca, with its broken streets and ramshackle pit houses! How much of this had been built by Riorcan slave labor?

Two Legaciatti, both women, met them inside the door. Vitala studied them, curious at the oddity of female Kjallan soldiers. Bayard had told her that women made ideal assassins for Kjallan targets because Kjallan men didn’t take women seriously. Ostensibly, that was true; Kjall was patriarchal, and women had little power under the law. But as she’d traveled on the tournament circuit, she’d learned the reality was more complicated. Most Kjallan men were soldiers who were often away from home. In their absence, their wives had authority over their households. Women and slaves were the real engine of Kjall’s economy; few men had many practical skills outside of soldiering.

“Search her,” ordered Remus.

One of the women beckoned. “Come along.”

The search took place in a private room and was humiliatingly thorough. Vitala knew what they were looking for: concealed weapons or perhaps a riftstone. They would not find either. She didn’t wear her riftstone around her neck; it was surgically implanted in her body, along with the deathstone, her escape from torture and interrogation if she botched this mission. Her weapons were magically hidden where none but a wardbreaker could detect them. And there were no Kjallan wardbreakers; only Riorcans possessed the secrets of that form of magic.

As she put her clothes back on, the Legaciatti emptied her valise, checked it for hidden compartments, and pawed through her paltry collection of spare clothes, undergarments, powders, and baubles. They found nothing that concerned them.

They repacked her things and led her up two flights of white marble stairs. The walls were rounded and concave; she must be in one of the domes. Her room was the third on the right from the top of the stairway. A young guard with peach fuzz on his chin stood in front of it, wearing an orange uniform but no sickle and sunburst. Peach fuzz. He looked familiar.

The young soldier lay on the cot, his wrists and ankles bound. His blanket had fallen to the floor, a result of his struggles. His eyes jerked toward her, wide with fear, but when he saw her, he relaxed a little. He wasn’t expecting a teenage girl.

“Miss Salonius?”

He shouldn’t know her name. How did he know her name?

“Miss Salonius?”

And why did he sound like a woman?

Vitala blinked. The Legaciatti were staring at her in concern. “Miss Salonius?” one of them asked.

“I’m sorry.” Gods, where was she? Marble walls. The Imperial Palace.

“You stopped moving. You were staring into space.”

“Sorry, I was . . . never mind.” Averting her eyes so that she wouldn’t see the young man guarding her door, she stepped inside.

Vitala’s room was a suite. Just inside was a sitting room with a single peaked window along its curved wall and a pair of light-glows in brass mountings suspended from the ceiling. The room was lavishly furnished with carved oaken tables and chairs upholstered in silk. A bookshelf on the far wall drew her eye. Among its contents, she recognized all the classic treatises on Caturanga and some she’d never seen before, as well as books on other subjects. An herbal by Lentulus. Cinna’s Tactics of War. Numerous works of fiction, including the notoriously racy Seventh Life of the Potter’s Daughter. Who had put that a book like that into an otherwise erudite bookshelf?

On a table in the center of the room sat the finest Caturanga set she’d ever seen. Pieces of carved agate with jeweled eyes winked at her from a round, two-tiered board of polished marble. She picked up one of the red cavalry pieces. The rider was richly detailed down to the folds of his cloak. The warhorse was wild-eyed, his beautifully carved expression showing equal parts fear and determination.

Had Emperor Lucien set up this room just for her? No, of course not. He hosted many Caturanga champions. Probably all of them had been housed here.

The bedroom was equally fine, with a high, four-poster bed, silk sheets, and a damask down-stuffed comforter. The silk hangings were blue and red. Was that by design? Blue and red were the traditional colors of Caturanga pieces.

“You will reside here until the emperor summons you,” a Legaciatta instructed. “Take your rest as needed, but you are not to wander about the palace. If you desire something, such as food or drink, ask the door guard. If you wish to bathe, he can escort you to the baths on the lower level.”

Vitala nodded. “Thank you, ma’am.”

The Legaciatti left, closing the door behind them. Vitala went to the window—real glass, she noted—and peered out. Below was a walled enclosure obscured by a canopy of trees, through which she caught glimpses of red, purple, and orange. The famous Imperial Garden? Looking up to take in the broader view, she noticed a patch of too-light blue in the sky and picked out the Vagabond, the tiny moon that glowed blue at night but faded almost to invisibility in the daytime. God of reversals and unforeseen disaster, the Vagabond wandered across the sky in the direction opposite the other two moons, and was not always a favorable sighting. “Great One, pass me by,” she prayed reflexively.

Leaving the window and lighting one of the glows with a touch of her finger, she pulled Seventh Life from the bookshelf. Sprawling on a couch, she waited upon the pleasure of the emperor.

Vitala was not her given name. When she was born dark-haired, Papa named her Kolta: “blackbird.”

She was eight years old when the stranger arrived. Mama and Papa took him into the bedroom to speak with him. They shut her out, but she pressed her ear against the door to listen.

“We’ve completed the testing,” said the stranger, “and your daughter is exactly what we’re looking for. Highly intelligent, physically strong, and coordinated. And, of course, she’s black-haired.”

Mama said something she couldn’t quite make out.

“In the village, perhaps,” replied the stranger. “But in the Circle, dark hair is an asset. She can pass for Kjallan. It will allow her to move in areas where others cannot.”

More mumbling from Mama.

“The Circle is prepared to offer you compensation. Four hundred tetrals.”

Papa gasped.

Mama raised her voice. “I’m not selling my daughter!”

“Of course not,” soothed the stranger. “But Kolta will never reach her potential here in the village—not with the prejudice against girls like her. Why subject her to harassment and ostracism, when among the Circle she will be valued and revered? The money is our gift to you. A token of our thanks for aiding Riorca in its time of need.”

Mama began to sob.

“Treva, he’s right,” said Papa. “It would be selfish to keep Kolta here. A half-Kjallan bastard will never be accepted—”

“You hate her!” cried Mama. “You want to be rid of her!”

“Madam,” said the stranger, “consider the advantages to Kolta in joining the Circle. She will receive a thorough education, far better than anything she could get here. And she will be among her own kind. We have other half-breeds like her, dark-haired girls who know what it’s like to be Riorcan but look Kjallan. For the first time in her life, she will have friends.”

Mama continued to sob.

“Treva, think of it,” said Papa. “Four hundred tetrals! You know what that money would mean for us. This man is right. The Circle can do far better for Kolta than we can.”

Something unintelligible from Mama.

“No,” said the stranger. “It must be now. She must begin her language training immediately, or she’ll never speak with the proper accent.”

A long silence followed, broken only by Mama’s sobbing. There were soft words that Kolta could not make out.

The stranger was saying, “We find it’s best if there are no good-byes.”

The door opened, and the stranger stepped out. Terrified, Kolta hid in the corner between the wall and the door. But the door moved away, revealing her. The stranger stared down at her in surprise. “Were you listening, Kolta?”

She shook her head.

He knelt, bringing himself to her eye level. “Tell me the truth, and you will not be in trouble. Were you listening?”

She hesitated a moment, but nodded.

“And yet you do not cry.” His mouth twisted as he lifted her chin with his finger. “My name is Bayard. I’m going to be your friend, Kolta. Would you like that?”

She was silent.

“The people here don’t treat you very well, do they? They don’t like dark-haired girls. But I’m going to take you somewhere else. Somewhere you’ll be loved, Kolta. Do you want to be loved?”

Her chin began to tremble.

“Of course you do.” He folded her into his arms, and she began to cry. “It’s what we all want.”

Lucien limped on his artificial leg his way through the doorway into his office, fell into his chair, and leaned his crutch against the wall. Three years he’d been emperor, and still a shiver went down his spine every time he crossed that threshold. He’d spent too much time in the opposite chair, the one on the other side of the desk, facing a loud and frightening father he could never please.

Septian, his bodyguard, a head taller than Lucien and twice as broad, moved in almost perfect silence as he took his customary place behind the chair and shouldered a musket. He carried the weapon more for show than for any real need; it would be a rare enemy Septian couldn’t handle with a sword or a knife or even his bare hands. Lucien had been escorted by Legaciatti all his life, but since ascending the throne, he’d become hyperaware of them, especially Septian. The man rarely spoke, and his face was impossible to read. What did he think of Lucien? Did he recognize Lucien’s head for military strategy? Or, like Florian, did he privately roll his eyes at what he perceived as a useless, crippled boy?

Lucien rubbed his forehead. His empire was fragile, precarious. He had problems to solve. Real problems. What his bodyguards thought of him should be the least of his concerns.

Septian cleared his throat.

Lucien raised his head and saw the man standing in the doorway. “Remus. Come.”

The Legaciattus entered, bowed his obeisance, and sat in the chair across from him. The door guards shut him in.

“What’s the schedule today?” asked Lucien.

“You’re seeing Legatus Cassian Nikolaos this morning.”

Lucien made a face. “Pox. Is he waiting outside?”

“Yes, sir. And this afternoon, you were going to speak to the new recruits at the palaestra. Then there’s the meetings with your advisors.”

Lucien nodded. The morning would be a harassment, but the afternoon wasn’t so bad. He liked public speaking, especially when the audience was young soldiers—it wasn’t long since he’d been one himself. He’d seen action on the battlefield, and frontline soldiers tended to respect that.

Was there a gap in his schedule? His meeting with Cassian would not take all morning. “Remus, has that woman who won in Beryl arrived yet?”

Remus smiled. “She arrived by ship yesterday, Your Imperial Majesty, and awaits your pleasure.”

Lucien brightened. “Have her ready to play by midmorning.”

“Very good, Your Imperial Majesty. Shall I send in Cassian?”

“Yes.”

Remus left, and the guards admitted Legatus Cassian Nikolaos, Lucien’s highest-ranking military officer. Cassian was a longtime friend of Lucien’s father, the former emperor, and he was everything Lucien wasn’t. Big, burly, whole—that is, possessed of all four limbs—and afraid of nothing. Middle-aged, he had decades of command experience behind him, and it rankled him to report to an emperor in his twenties. “Legatus,” said Lucien, granting the man permission to speak.

“Your Imperial Majesty.” Cassian bowed.

Lucien’s eyes narrowed. The bow wasn’t as low as it ought to be. It bordered on insolence, yet the slight was subtle. He would look foolish if he drew attention to it. “Have a seat.” He’d tried several strategies for winning Cassian’s respect. Flattery hadn’t worked. Neither had pointing out the patently obvious holes in the man’s proposed strategies. In the end, he’d given up and fallen back on the style he’d used with his equally intractable father, a tone of breezy, uncaring confidence. It didn’t work either.

Cassian began, “Lucien, about the Riorcan rebels—”

“That’s Sir or Your Imperial Majesty,” snapped Lucien. “And I’m not going to decimate the Riorcans.”

Cassian stiffened. “Sir, you’ve let their crimes go unpunished far too long. They flaunt their disrespect in a hundred tiny ways every day, and their Obsidian Circle sabotages our supply lines and assassinates our officers.”

“I have a battalion combing the hills in search of the Circle. It’s not easy to find. In the past year, we’ve found only two enclaves, neither of which had more than twenty people in it. And you know what my soldiers discovered when they broke in.”

“Corpses,” said Cassian.

“They killed themselves rather than risk interrogation. We know nothing about where their headquarters are or who’s in charge.”

“Sir, this is why you have to decimate the Riorcan villages. We can’t find the Circle, but we can find the villagers who support them. Punish them, and that support will end.”

“Cassian.” Lucien paused, considering his words carefully. “You are one of Kjall’s finest commanders, and I have a tremendous respect for your experience in the field. But you haven’t been in Riorca. I have—”

“For two years!” spat Cassian.

“Two years longer than you have, and those years opened my eyes. Most Riorcans want nothing more than to live their lives and raise their families in peace. The rebels are a minority. Your opinion is noted, but my mind is made up. We will not decimate Riorca.”

“Yes, sir.” Instead of leaving, Cassian sat quietly in his chair.

Lucien eyed him narrowly. “You are dismissed, Legatus.”

“Sir, about last night’s state dinner . . .” He hesitated.

“Didn’t like my speech?”

“Your oration was superlative and the food exquisite. But you deprived us of the court’s brightest jewel, the imperial princess.”

Lucien’s mouth tightened. “Celeste chose not to attend.”

“At your urging, no doubt.”

“She is thirteen years old, Legatus, and she finds state dinners tedious.” Indeed, he could hardly blame his sister for not wanting to spend an evening being slobbered over by older men looking to insert themselves into the line of succession. In Cassian’s case, it was particularly disgusting, because he was already married. He would divorce his wife in a heartbeat if he thought he could remarry more advantageously. And while politically motivated divorces and marriages were common in Kjall, Lucien considered the practice repugnant.

“Perhaps she found them dull when she was a child, but she’s a young woman now. Young women love to be the center of attention. Perhaps she would like to attend the upcoming dinner for the Asclepian delegates? I should be glad to escort her.”

Lucien stared at him stonily. “No.”

“If you should change your mind—” began Cassian.

“You are dismissed, Legatus.”

Vitala paced nervously in her suite. The door guard—a new one, thank the gods; there must have been a shift change—had informed her the emperor would see her later that morning. Soon, the moment would come, the moment she’d spent eleven years preparing for. Could she seduce and kill Emperor Lucien?

Seduction was the easy part, but she’d never targeted an emperor before.

We know very little about his love life, Bayard had told her. Only that he must have one.

What if he liked only blondes or redheads? Gods, what if he preferred men?

She’d suggested to Bayard that she lose her first Caturanga game with Lucien. She’d seduced a Kjallan officer once with a similar technique. She played the part of a foolish bufflehead searching for a misplaced glove, which turned out to be under her chair. A little flattery and flirtation, a touch here and there, and he was hers. But soldiers were easy; an emperor was something else. Lucien was probably approached by beautiful, sexually receptive women on a daily basis. She had to make herself stand out.

You must win the initial game, Bayard had said. He may lose interest if he thinks you have nothing to teach him. And we don’t know how long it will take you to lure him into bed. This man is powerful. He has his choice of women. And he may be particular.

Thanks for the encouragement, she had retorted.

We suspect he likes strong women.

How can you tell, if you know nothing about his love life? she asked.

Because the closest relationship he’s ever had with a woman was with his cousin Rhianne, said Bayard.

The one who ran off to Mosar?

She was rebellious as a child, and Lucien was her partner in crime. Word is he misses her. We think the more you remind him of Rhianne, the more interested in you he’ll be.

Fine. She would win the first game. But how to proceed from there?

Someone knocked at her door. “Miss Vitala? His Imperial Majesty will see you now.”