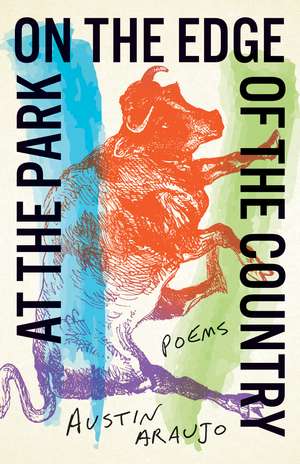

At the Park on the Edge of the Country: Poems: The Journal Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize

Autor Austin Araujoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 feb 2025

In At the Park on the Edge of the Country, Austin Araujo maps the intricacies of memory, immigration, and belonging through the experiences of one Mexican American family—his own—in the rural American South, crystallizing memory and self-knowledge as collaborative, multivocal affairs. Human and nonhuman voices and the competing landscapes of childhood and adulthood propel these poems, offering an unyielding portrait of a family’s endless encounters with the shortcomings of citizenship. Speakers sleep like tostadas, mistake hikers crossing a small river in Arkansas for a migrant father, and hold onto silence through difficult conversations in the fields and in the city. Revelatory and striking, these poems reinvent origin myths to unmask the contradictory and expansive astonishments of Mexican American identity in the twenty-first century.

Preț: 84.96 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.26€ • 17.38$ • 13.55£

16.26€ • 17.38$ • 13.55£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-11 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814259368

ISBN-10: 0814259367

Pagini: 72

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria The Journal Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize

ISBN-10: 0814259367

Pagini: 72

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria The Journal Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize

Recenzii

“Simply cinematic—utterly memorable and moving. In these fierce and fiery poems of goldenrod and tostadas, Araujo covers satisfying and crackling ground. An imaginative debut.” —Aimee Nezhukumatathil

“The lushness of the language, the precision of the images, the humor, the deft and digressive narratives—these poems are so beautiful. But I am most moved by and keep going back to the wrenching, complicated, grown-ass poems about fathers, and about fathers and sons: by how patient Araujo is in those poems, how he lets them answer to music, and love.” —Ross Gay

“From the peripheries of oblivion, Austin Araujo coaxes honey from rock to deliver us At the Park on the Edge of the Country. . . . These poems of sensorial majesty enact the continuous process of becoming human. Their specificity, propulsive action, and deft panning from Arkansas to California and across generations remind me how miraculous the overlooked elements are of the worlds we build with our own two hands—how like reclaimed magic, inevitable and necessary.” —Paul Tran

Notă biografică

Austin Araujo is a writer from northwest Arkansas. The recipient of a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University, his poems have appeared in Poetry,TriQuarterly, and Gulf Coast. At the Park on the Edge of the Country is his first book.

Extras

Another Crossing

The river sloughs off mist, elk approach

its banks for a drink. Moon perched

in the mezzanine of the night. Dogs clamor

for each other miles away. I settle

onto this stone seat trying hard to see anything

but the men stepping into the rushing water,

each holding a small bag over his head. Striding

into the silence I’ve embraced. What crossings

can be made when already in Arkansas?

One of them falls hard into the White River,

foot probably catching on some rock’s jag.

Those in front keep walking, those behind

go around his brief thrashing below the surface.

His mouth opens with ¡estoy bien!

when he rises, which disturbs the elk

who look up so that they might study him

with me, so that we all might behold the man

who is suddenly here, who, of course,

resembles my father, droplets tumbling

from his creased brow back into the current.

He blows snot from each nostril and runs

his fingers through the hair almost landing

on his shoulders as it does in my father’s first photo

ID, taken in Mexico, listing the wrong birthday,

catching him as a teen, looking like this guy

hauling his hand across the surface of the water.

He works hard to match pace, impossible, like my dad

in the White River, crossing twenty-odd years

after the fact. Who needs dreams when I’ve got eyes.

The others emerge by the shore, disappear

into the woods, refuse to wait. The elk and me,

welcome committee. A stranger climbs into the bramble

where he hollers, gaining ground on the group.

Sight and Sound

Roxie Theater, San Francisco

I am led into the dark

cinema for a restored

print of a major work

by David Lynch

he speaks to us

in a previously recorded

introduction

every now and again

I try to turn my head

an imperceptible degree

to catch you in the glow

I am taking stock

of how I feel

suspicious

but of what

there’s a woman

who makes occasional

smart comments

there’s a man

eating chocolate

and popcorn

in fistfuls

your hand opens

for potential touching

holding your

perfume in my mouth

your leather skirt

squeaks in the seat

the sun’s laboring

across the finish line

when we leave the theater

we walk toward

the bar where I’ll lose

my wallet

in the film

a man with a powdered face

says hello at a party

in one of those big LA houses

he says hello on the phone too

he likes to watch people sleep

the main character

becomes someone else

driven by formless desires

I am afraid I am

alive I am turning

twenty-six today

at an auto shop

the young man

he has become is pulled

or manipulated between

the forces of duty

the forces of desire

cars are lifted hoods

popped some force

tells him come to

the desert I am still

pulling myself

apart when you order

cocktails I am still

A Mexican American Novel

The novel includes a protagonist with a mysterious scar slashed across his scrotum as well as numerous references to tax fraud, bruised fruits, and last names. A year-in-the-life type of tale. In a pivotal September scene, he asks his father whether anything weighs more than madness. (Readers will know the man’s frown counts for an answer.) Then a flashback to when the father crushed his five-year-old son’s fingers with a rising car window. A chapter entitled “Robert Hayden Was Rarely Wrong.” The boy wanders from light source to light source: big moons, small lanterns, candles, burnt-out bulbs hanging on grocery store ceilings, and the various deep purples of a beloved’s bedroom. I’m working out how he’ll talk to lovers, but his legs will shake, bare but for goosebumps rising around his knees. In the first paragraph, the boy presses a guitar into a cloth case. By the end of the year, he’ll understand what symbolizes great human suffering and what of the ordinary self remains.

The river sloughs off mist, elk approach

its banks for a drink. Moon perched

in the mezzanine of the night. Dogs clamor

for each other miles away. I settle

onto this stone seat trying hard to see anything

but the men stepping into the rushing water,

each holding a small bag over his head. Striding

into the silence I’ve embraced. What crossings

can be made when already in Arkansas?

One of them falls hard into the White River,

foot probably catching on some rock’s jag.

Those in front keep walking, those behind

go around his brief thrashing below the surface.

His mouth opens with ¡estoy bien!

when he rises, which disturbs the elk

who look up so that they might study him

with me, so that we all might behold the man

who is suddenly here, who, of course,

resembles my father, droplets tumbling

from his creased brow back into the current.

He blows snot from each nostril and runs

his fingers through the hair almost landing

on his shoulders as it does in my father’s first photo

ID, taken in Mexico, listing the wrong birthday,

catching him as a teen, looking like this guy

hauling his hand across the surface of the water.

He works hard to match pace, impossible, like my dad

in the White River, crossing twenty-odd years

after the fact. Who needs dreams when I’ve got eyes.

The others emerge by the shore, disappear

into the woods, refuse to wait. The elk and me,

welcome committee. A stranger climbs into the bramble

where he hollers, gaining ground on the group.

Sight and Sound

Roxie Theater, San Francisco

I am led into the dark

cinema for a restored

print of a major work

by David Lynch

he speaks to us

in a previously recorded

introduction

every now and again

I try to turn my head

an imperceptible degree

to catch you in the glow

I am taking stock

of how I feel

suspicious

but of what

there’s a woman

who makes occasional

smart comments

there’s a man

eating chocolate

and popcorn

in fistfuls

your hand opens

for potential touching

holding your

perfume in my mouth

your leather skirt

squeaks in the seat

the sun’s laboring

across the finish line

when we leave the theater

we walk toward

the bar where I’ll lose

my wallet

in the film

a man with a powdered face

says hello at a party

in one of those big LA houses

he says hello on the phone too

he likes to watch people sleep

the main character

becomes someone else

driven by formless desires

I am afraid I am

alive I am turning

twenty-six today

at an auto shop

the young man

he has become is pulled

or manipulated between

the forces of duty

the forces of desire

cars are lifted hoods

popped some force

tells him come to

the desert I am still

pulling myself

apart when you order

cocktails I am still

A Mexican American Novel

The novel includes a protagonist with a mysterious scar slashed across his scrotum as well as numerous references to tax fraud, bruised fruits, and last names. A year-in-the-life type of tale. In a pivotal September scene, he asks his father whether anything weighs more than madness. (Readers will know the man’s frown counts for an answer.) Then a flashback to when the father crushed his five-year-old son’s fingers with a rising car window. A chapter entitled “Robert Hayden Was Rarely Wrong.” The boy wanders from light source to light source: big moons, small lanterns, candles, burnt-out bulbs hanging on grocery store ceilings, and the various deep purples of a beloved’s bedroom. I’m working out how he’ll talk to lovers, but his legs will shake, bare but for goosebumps rising around his knees. In the first paragraph, the boy presses a guitar into a cloth case. By the end of the year, he’ll understand what symbolizes great human suffering and what of the ordinary self remains.

Cuprins

Contents I. Another Crossing Sight and Sound A Mexican American Novel My Documentary The Tostada Translation At the Park on the Edge of the Country Within Earshot of 1991 Lost Year At Lake Temescal Aperture II. The Bull Clearing Watching Him Cross After Someone Is the Water Debut Another Look Sancho Panza Betting the House At the Park on the Edge of the White River The Father III. Gathering Jamboree, Evening, Midsummer On the Road to Irapuato Irapuato Mexican in the Meadow Early Conversation with My American Grandmother Maintenance My Condition In Body Sweet Brothers Notes Acknowledgments

Descriere

Poems that map the intricacies of memory, immigration, and belonging through the experiences of one Mexican American family in the rural American South.