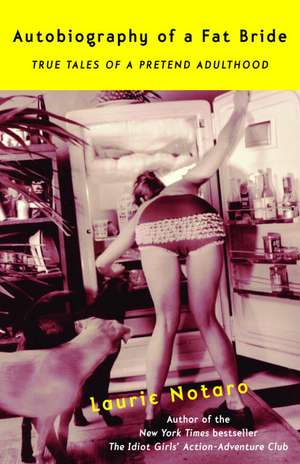

Autobiography of a Fat Bride: True Tales of a Pretend Adulthood

Autor Laurie Notaroen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003

In Autobiography of a Fat Bride, Laurie Notaro tries painfully to make the transition from all-night partyer and bar-stool regular to mortgagee with plumbing problems and no air-conditioning. Laurie finds grown-up life just as harrowing as her reckless youth, as she meets Mr. Right, moves in, settles down, and crosses the toe-stubbing threshold of matrimony. From her mother's grade-school warning to avoid kids in tie-dyed shirts because their hippie parents spent their food money on drugs and art supplies; to her night-before-the-wedding panic over whether her religion is the one where you step on the glass; to her unfortunate overpreparation for the mandatory drug-screening urine test at work; to her audition as a Playboy centerfold as research for a newspaper story, Autobiography of a Fat Bride has the same zits-and-all candor and outrageous humor that made Idiot Girls an instant cult phenomenon.

In Autobiography of a Fat Bride, Laurie contemplates family, home improvement, and the horrible tyrannies of cosmetic saleswomen. She finds that life doesn't necessarily get any easier as you get older. But it does get funnier.

Preț: 105.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.10€ • 21.84$ • 16.89£

20.10€ • 21.84$ • 16.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375760921

ISBN-10: 037576092X

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Villard Books

ISBN-10: 037576092X

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Villard Books

Notă biografică

Laurie Notaro has never written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, Harper's, The New Yorker, Lowrider, American Logger, Farm Show, or McSweeney's. She lives, and will probably die, in Phoenix, Arizona. Miraculously, this is her second book.

Extras

It’s Not You, It’s Me

I am the sucker.

Ben’s standing on the sidewalk, his hands in his pockets; his hair, normally straight and elbow-length, is now appallingly cornrowed as his head hangs toward the ground because I’ve caught him.

I’ve caught him.

He’s too goddamned scared to make a move and I don’t blame him, because he’s my boyfriend and I caught him, just now, packing up all of his crap into a piece-of-shit hippie van because he’s running off to Seattle to follow his dream, which is growing pot, smoking it, and learning to play Neil Young’s “Old Man” on an acoustic guitar in order to perform it as a birthday gift for his dad, a man he has never met.

He is running away.

With HER.

Turn to the right, there she is, standing behind the van, trying to hide from me; it’s Dog Girl, his ex-girlfriend, dressed in a tremendous gauze dress and with matching cornrow hair.

“She made the curtains,” he mutters, still looking at the sidewalk.

“WHAT?” I said, shaking my head.

“She made the curtains,” he repeats. “For the van. She sold her car and bought the van.”

For a moment, I’m confused and I wonder about what I’m supposed to do with this. Am I supposed to fight, and kick and scream, am I supposed to oppose it? I have no idea, and I don’t do anything. I just walk away.

“Don’t you want to hit me?” he calls out.

“Don’t you want to yell at me, tell me you hate me?” he yells to me.

I just shake my head, and keep walking.

“It’s not you!” he shouts one last time. “It’s me!”

That’s enough to make me stop dead in my tracks.

“Really?” I ask as I spin around. “Are you sure it’s you? Because that would make my day, just knowing that it was YOU and NOT ME, especially after I just caught you in the middle of an escape attempt. Is it you? Is it really you, Ben?”

“Well, I guess it’s me a little bit,” he stammers as Dog Girl peeks an eye out from behind the purple curtains as one of her hair ornaments chimes. “But, well, if you really want to know, I’d say that yeah, it’s mostly you.”

“Mostly me?” I reply. “It’s mostly me that’s forced you into this scene from Children of the Cornrow? God, it looks like Stevie Wonder and Bo Derek jumped you in an alley and gang-braided you!”

He stands quiet for a moment, thinking, then nods his head.

“Actually, it’s pretty much all you,” he adds with a sigh. “I don’t think it’s me at all. No, no, it’s you. All you. It’s not me, because the feeling that I’m getting in my chakras is that it’s definitely you.”

As if I needed confirmation. I’ve seen that play It’s Not You, It’s Me before, and as a matter of fact, I’ve played the lead in that scenario since before I had boobs.

My role is “Super Idiot Girl,” the kind of female who searches out the most alluring sociopath to date, who never learns that if you see a tornado coming, especially one that works in a record store and displays no other ambition outside of making mixed tapes from bootleg Grateful Dead shows, duck under the nearest table until the roar passes.

It all started in fifth grade, when my mother bought me a box of valentines from Kmart. I searched out the perfect Holly Hobbie valentine, a little farmer boy in overalls milking a cow, for the boy I wanted to move into sixth grade with. Only a few days earlier, he had passed me a note, chunkily folded in the shape of a football, that said, “Whats your shampew? Gee, your hair smels terrifick.” It absolutely declared the love that was to guarantee me perfect happiness for the rest of my life, or at least until summer vacation. In my best cursive handwriting, I signed the back of the valentine, “To Paul, I use Breck once a week. Luv, Laurie,” and, to add a sense of female intrigue, dotted the i’s with puffy hearts to let him know that I was all lady, all right.

I can understand now how that kind of message would be chilling enough for a boy to shy away from the love of an oily-headed, prepubescent girl, but I still don’t think it reached the proportions required for him to stand up during lunchtime and loudly scream, “I am NOT your boyfriend! I like Melissa Crow because she can sit on her hair and she has horses!”

When I transferred to junior high I already had a major crush on Mike Smithfield from my sixth-grade class, and had waited all summer to see him. I began parting my hair on the left out of compassion for his left-handedness, a somber physical disability that he bravely bore in a cruel right-handed world, which, at the same time, made it difficult for others to cheat off of him during tests. If I could tell that Mike Smithfield was a knight of gallantry and preeminence just by the way he faced the obstacle of the No. 2 pencil God had placed in his left hand, we were meant to be soul mates. Ideal husband material. For him, I relentlessly practiced my cutest smile, which I had noticed in a certain light was identical to the smile of the Elizabeth sister on Eight Is Enough, and entailed curling down the sides of my mouth and then innocently—yet strategically—pouting out my two front teeth slightly. I found it to be the perfect image of vulnerability and a girlish glow of a much-delayed, though still yet possible, sexual awakening. My mother, on the other hand, saw a premature appearance of the Elizabeth smile when she stormed into the bathroom one day and suddenly interrupted my practice time.

“Jesus Christ,” she said sharply in her native Brooklyn accent, “if you had that look on your face the day I brought you home from the hospital, I probably would have laid off the cigarettes when I was pregnant with your two younger sisters. Now, I don’t know what the hell you’ve been sniffing, but I’m telling you right now to get off smelling the paint or eating the glue or whatever, and from now on when I fill up the gas tank, you are staying in the car!!! I’ll be watching for deep breaths, you know! This isn’t the Linkletter house, for your information! No one in this house is getting drug crazed and then jumping off my goddamned roof! We just had that thing retarred!”

My mother had convinced herself that it was my destiny to one day simply fling myself off the roof like Art Linkletter’s daughter, who vaulted to her death from the top of a six-story apartment building after taking some drugs in 1969. I’m sure it was a frightening moment for my mother, who most likely looked at me when she heard the news flash and mumbled, “Over my dead body!” despite the fact that at the time, I didn’t even have the ability to chew, let alone the motor skills necessary to assemble a rig and shoot my fat little baby arm up with black-tar heroin. My “Art Linkletter’s Daughter” lessons started early, when I was about nine. It happened the day my mother dropped me off for school in our Country Squire station wagon and saw a sixth-grader wearing a tie-dyed T-shirt. “See that kid?” she said, grabbing my arm and pointing to the rainbow-colored figure swinging on the monkey bars. “I bet his parents are drug people. Hippies! You know what hippies eat for dinner?”

I shook my head. “Meat on Fridays?” I ventured.

“NO!” my mother informed me. “TRASH! Hippies eat trash! They go through their neighbors’ garbage and eat spoiled food because they spend all their money on drugs and art supplies! From now on, never take a piece of gum or candy from anyone BUT ME! Never take an aspirin or drink out of the same soda can from anyone BUT ME! There are people out there, LIKE THAT HIPPIE KID, who want to get you hopped up on drugs to be like them. One day, you take a piece of gum from a girl in your PE class that makes all of the colors very bright and the world a beautiful place and the VERY NEXT DAY, you’re eating rotten meat loaf out of Mrs. Kelch’s trash bin and you’re not wearing underwear. That’s a loose life! Art Linkletter’s daughter jumped off the roof after someone gave her some gum, and although nobody says it, I bet she ate trash, too. Is that the kind of life you want to lead? A loose life? IS IT?”

I spent a long time believing that a sabotaged stick of funky Juicy Fruit, a Mr. Pibb laced with a Bayer aspirin, or an angel dust–spiked Jolly Rancher would fill me with pulsating, uncontrollable urges to locate my father’s ladder, scramble up it, and then fling myself off our one-story spec house like a virgin sacrifice and then flatten my mother’s yucca plant like a lily pad. Honestly, in hindsight, I don’t think it was the possibility of my experiencing a drug-related death that scared my mother as much as the possibility of her being known as “Mrs. Notaro, who’s addict daughter jumped off the roof” that sunk a worry knife in her straight to the bone. However, since I believed that most of the people in my environment were trying to get me to fly off a roof (that is, until I was twenty-five and finally understood that no one gives away free drugs to people they don’t know because friends always come first), I was faced with an undeniable love dilemma when I saw Mike Smithfield on the first day of middle school.

I spotted him poised at the trash can in the cafeteria, his tray held gingerly with his left hand, and I rushed over to say hi. He nodded, smiled slightly, and I gawked.

A tense, long moment passed before he said suddenly, “Um, want this Snoball?” and pointed to the pink, coconut-flecked mound that teetered on the edge of the tray, a mere millisecond away from mating with a cold, mottled Salisbury-steak patty that waited eagerly in the trash heap below. A four-star hippie dinner, I remembered thinking.

Understanding the potential of a poisoned bakery product, I was naturally wary, though the spongy, marshmallowy goodness and the fluffy-filling creaminess called out to my spiking hormones in nothing less than a siren song. No, Mike Smithfield was not my mother. That was true. But he was a lefty. An underdog. A social cripple. He understood pain, he knew it well. Those who weep are the last ones to cause a tear. I believed I could trust him. Besides, if he needed me to jump off a roof to prove my love, I would soar like an ostrich.

I nodded back and slowly looked up as I launched the Elizabeth smile, poked out my two donkey teeth, and plucked up the Snoball with my left hand. Knowing that this Snoball gift was a sure sign of tender affection, and given the fact the I was wearing my new, cute pair of brick-red Dittoes, I sucked up all of my courage in one deep breath and said, “Wanna go with me to the Sadie Hawkins dance on Friday?”

“No,” he said simply, but I didn’t believe him. I knew better. Boys will be shy. They are afraid of love, I told myself, you must coax them, show them the love light. I followed him all the way to his PE class at the gym with the Elizabeth smile frozen on my face as I asked, “Why? Why won’t you go with me? Why?” until we hit the baseball field and he just took off running. He ran the entire length of the field, constantly looking over his shoulder to see if I was still chasing him. I stood there for a long time, understanding slowly that Snoballs, although pink and soft, didn’t always mean love. At that precise moment, Patti Herman, the first girl who smoked at our school and the one most likely to force you to eat a hallucinogenic stick of Big Red in the girls’ bathroom, walked by me and said, “Hey! Do you think your pants are tight enough, Cameltoe? You don’t even need to wear pants if you’re going to show off your cookie like that!”

Things weren’t about to get better, even after that.

My romantic life took a violent turn my sophomore year in high school. I was adoringly watching Jim Kroeger, a senior, play basketball in the gym when he called my name for the first time. I turned around and flashed my biggest, brightest, newly practiced Chrissy Snow bucktoothed smile just in time for him to bounce the basketball right off my head. I got up, dazed but still smiling amid the laughter rolling in waves around me, and smiled all the way to the nurse, who looked at the round, patterned welt on my forehead and asked me if I had seizures often.

Later in high school, I dated an older, nearly high school graduate from Los Angeles whom I worked with at a Pizza D’Amore (The Pizza of Love) in the mall. With romance sparking between every dough ball and sprinkle of mozzarella, our eyes met, except the one he had that was a little bit lazy. When he pulled in front of my house that night in a green Chevy van with the windows painted black, my mother chased him away, waving a dish towel and screaming, “Put it in reverse and back it up, buddy! You’re not getting your greasy pizza paws on my kid, Mr. California!”

In college, I had enough experience that I should have taken note of the red flag when it popped up on dates, especially on the ones when the guy was already drunk when I went to pick him up. It was always a bad sign, because I figured if I had the foresight to remain sober for the most promising portion of the date, the guy should have the same kind of hope, too. One such potential mate, now referred to by friends as “The Horror of Todd,” was a guy that I met in a communications law class who was not only drunk when I went to pick him up, he was unconscious. After my pounding at the front door woke him up, he accompanied me to dinner and proceeded to eat an entire cheeseburger without the use of his hands. He would look up every now and then, his face smeared with ketchup, meat flecks, and chewed-up bits of lettuce, and simply whine at me like a hyena at a carcass.

I, on the other hand, was determined to work things out. I tried as hard as I could to pretend that everything was fine, saying things like “So, how long did it take you to make the rainbow—oh, I’m sorry, light prism—in your living room out of beer bottles?” “I think it’s fascinating that you can play every Dave Matthews song by blowing into a beer bottle,” “It takes a certain kind of talent to make a wind chime out of a beer bottle,” and “No, Todd, I really don’t think that will fit up your nose, being that it’s a beer bottle.”

I began dating another guy I met at a bar until I found him engaged in a random sex act with a teenaged dairy queen, her little red apron crumpled up at the foot of the couch, but that was really okay because I was looking for a way out ever since I found a Special Olympics medal in his room. It gave me the opportunity to return his gift of the Lego block version of the Millennium Falcon that I thought was so wacky and displayed a madcap sense of humor instead of his current stage of mental development. I finally understood that he just may not have had a serious drinking problem after all, and figured it might be a wise idea to call a lawyer and prepare for my courtroom defense. My boyfriend after that planted his seed in a uterus that wasn’t mine, and I eventually got over it by losing thirty pounds and dating his best friend, who then realized girls really grossed him out.

So I graduated from college with a degree in journalism and was ready to find my dream job at a newspaper in addition to one good man who owned his own car and was certain about his sexuality, my two new, revised qualifying criteria for a potential date.

I had the exceptional bad fortune to enter the job market at the same time the morning daily newspaper bought out the afternoon daily newspaper, merged the two, and 250 reporters and editors found themselves without employment. Though I successfully scored an interview at another small paper as an obituary writer, I eventually lost out to a former features editor with twenty years’ experience.

So I began my life as Brenda Starr, cub receptionist for a small music distributor. My friend Kate worked there in the accounting department, and mentioned that the last receptionist had been let go after she was found naked at her desk, talking to clients who didn’t actually exist. It was an easy job. I didn’t have to dress up, just remain dressed, and I was hired on the spot after I reassured the general manager that I had never heard or, most important, answered to voices that called out to me from beyond demanding that I disrobe. The job had two perks: a 25 percent employee discount on records and the option that I didn’t have to wear my Wonderbra if I didn’t want to. In fact, it was encouraged that I leave it in a drawer at home.

There were plenty of handsome boys working in the warehouse, but I figured it would be wise not to shit where I ate. Besides, the handsomest one—this guy with alluringly sensitive eyes—would barely speak to me, even though I tried desperately to impress him with my knowledge and expertise at the copy machine. I was a college graduate, after all. He had a warm smile and those incredible eyes that avoided all contact with mine, almost like I was a tick that was trying to suck out his soul with my womanly stare. I tried to break the ice one day when one of his copies jammed, so I immediately jumped up to perform surgery on the machine, successfully freeing the renegade sheet of paper. I showed him the culprit and closed up the innards, but his response was slightly less than the magnificent awe I was expecting. He looked at me for only a moment, grabbed the paper from my hand, and then fled back into the warehouse.

Kate laughed when I recounted the story later that day, and I was horrified when she pointed out a little tiny booger in my left nostril that poked its milky, wormy head out every time I exhaled. Then we met up for happy hour, and Kate bought me a drink after work, and we toasted the fact that mucus was a beautiful preventative measure to shitting where you were about to take a big bite.

I am the sucker.

Ben’s standing on the sidewalk, his hands in his pockets; his hair, normally straight and elbow-length, is now appallingly cornrowed as his head hangs toward the ground because I’ve caught him.

I’ve caught him.

He’s too goddamned scared to make a move and I don’t blame him, because he’s my boyfriend and I caught him, just now, packing up all of his crap into a piece-of-shit hippie van because he’s running off to Seattle to follow his dream, which is growing pot, smoking it, and learning to play Neil Young’s “Old Man” on an acoustic guitar in order to perform it as a birthday gift for his dad, a man he has never met.

He is running away.

With HER.

Turn to the right, there she is, standing behind the van, trying to hide from me; it’s Dog Girl, his ex-girlfriend, dressed in a tremendous gauze dress and with matching cornrow hair.

“She made the curtains,” he mutters, still looking at the sidewalk.

“WHAT?” I said, shaking my head.

“She made the curtains,” he repeats. “For the van. She sold her car and bought the van.”

For a moment, I’m confused and I wonder about what I’m supposed to do with this. Am I supposed to fight, and kick and scream, am I supposed to oppose it? I have no idea, and I don’t do anything. I just walk away.

“Don’t you want to hit me?” he calls out.

“Don’t you want to yell at me, tell me you hate me?” he yells to me.

I just shake my head, and keep walking.

“It’s not you!” he shouts one last time. “It’s me!”

That’s enough to make me stop dead in my tracks.

“Really?” I ask as I spin around. “Are you sure it’s you? Because that would make my day, just knowing that it was YOU and NOT ME, especially after I just caught you in the middle of an escape attempt. Is it you? Is it really you, Ben?”

“Well, I guess it’s me a little bit,” he stammers as Dog Girl peeks an eye out from behind the purple curtains as one of her hair ornaments chimes. “But, well, if you really want to know, I’d say that yeah, it’s mostly you.”

“Mostly me?” I reply. “It’s mostly me that’s forced you into this scene from Children of the Cornrow? God, it looks like Stevie Wonder and Bo Derek jumped you in an alley and gang-braided you!”

He stands quiet for a moment, thinking, then nods his head.

“Actually, it’s pretty much all you,” he adds with a sigh. “I don’t think it’s me at all. No, no, it’s you. All you. It’s not me, because the feeling that I’m getting in my chakras is that it’s definitely you.”

As if I needed confirmation. I’ve seen that play It’s Not You, It’s Me before, and as a matter of fact, I’ve played the lead in that scenario since before I had boobs.

My role is “Super Idiot Girl,” the kind of female who searches out the most alluring sociopath to date, who never learns that if you see a tornado coming, especially one that works in a record store and displays no other ambition outside of making mixed tapes from bootleg Grateful Dead shows, duck under the nearest table until the roar passes.

It all started in fifth grade, when my mother bought me a box of valentines from Kmart. I searched out the perfect Holly Hobbie valentine, a little farmer boy in overalls milking a cow, for the boy I wanted to move into sixth grade with. Only a few days earlier, he had passed me a note, chunkily folded in the shape of a football, that said, “Whats your shampew? Gee, your hair smels terrifick.” It absolutely declared the love that was to guarantee me perfect happiness for the rest of my life, or at least until summer vacation. In my best cursive handwriting, I signed the back of the valentine, “To Paul, I use Breck once a week. Luv, Laurie,” and, to add a sense of female intrigue, dotted the i’s with puffy hearts to let him know that I was all lady, all right.

I can understand now how that kind of message would be chilling enough for a boy to shy away from the love of an oily-headed, prepubescent girl, but I still don’t think it reached the proportions required for him to stand up during lunchtime and loudly scream, “I am NOT your boyfriend! I like Melissa Crow because she can sit on her hair and she has horses!”

When I transferred to junior high I already had a major crush on Mike Smithfield from my sixth-grade class, and had waited all summer to see him. I began parting my hair on the left out of compassion for his left-handedness, a somber physical disability that he bravely bore in a cruel right-handed world, which, at the same time, made it difficult for others to cheat off of him during tests. If I could tell that Mike Smithfield was a knight of gallantry and preeminence just by the way he faced the obstacle of the No. 2 pencil God had placed in his left hand, we were meant to be soul mates. Ideal husband material. For him, I relentlessly practiced my cutest smile, which I had noticed in a certain light was identical to the smile of the Elizabeth sister on Eight Is Enough, and entailed curling down the sides of my mouth and then innocently—yet strategically—pouting out my two front teeth slightly. I found it to be the perfect image of vulnerability and a girlish glow of a much-delayed, though still yet possible, sexual awakening. My mother, on the other hand, saw a premature appearance of the Elizabeth smile when she stormed into the bathroom one day and suddenly interrupted my practice time.

“Jesus Christ,” she said sharply in her native Brooklyn accent, “if you had that look on your face the day I brought you home from the hospital, I probably would have laid off the cigarettes when I was pregnant with your two younger sisters. Now, I don’t know what the hell you’ve been sniffing, but I’m telling you right now to get off smelling the paint or eating the glue or whatever, and from now on when I fill up the gas tank, you are staying in the car!!! I’ll be watching for deep breaths, you know! This isn’t the Linkletter house, for your information! No one in this house is getting drug crazed and then jumping off my goddamned roof! We just had that thing retarred!”

My mother had convinced herself that it was my destiny to one day simply fling myself off the roof like Art Linkletter’s daughter, who vaulted to her death from the top of a six-story apartment building after taking some drugs in 1969. I’m sure it was a frightening moment for my mother, who most likely looked at me when she heard the news flash and mumbled, “Over my dead body!” despite the fact that at the time, I didn’t even have the ability to chew, let alone the motor skills necessary to assemble a rig and shoot my fat little baby arm up with black-tar heroin. My “Art Linkletter’s Daughter” lessons started early, when I was about nine. It happened the day my mother dropped me off for school in our Country Squire station wagon and saw a sixth-grader wearing a tie-dyed T-shirt. “See that kid?” she said, grabbing my arm and pointing to the rainbow-colored figure swinging on the monkey bars. “I bet his parents are drug people. Hippies! You know what hippies eat for dinner?”

I shook my head. “Meat on Fridays?” I ventured.

“NO!” my mother informed me. “TRASH! Hippies eat trash! They go through their neighbors’ garbage and eat spoiled food because they spend all their money on drugs and art supplies! From now on, never take a piece of gum or candy from anyone BUT ME! Never take an aspirin or drink out of the same soda can from anyone BUT ME! There are people out there, LIKE THAT HIPPIE KID, who want to get you hopped up on drugs to be like them. One day, you take a piece of gum from a girl in your PE class that makes all of the colors very bright and the world a beautiful place and the VERY NEXT DAY, you’re eating rotten meat loaf out of Mrs. Kelch’s trash bin and you’re not wearing underwear. That’s a loose life! Art Linkletter’s daughter jumped off the roof after someone gave her some gum, and although nobody says it, I bet she ate trash, too. Is that the kind of life you want to lead? A loose life? IS IT?”

I spent a long time believing that a sabotaged stick of funky Juicy Fruit, a Mr. Pibb laced with a Bayer aspirin, or an angel dust–spiked Jolly Rancher would fill me with pulsating, uncontrollable urges to locate my father’s ladder, scramble up it, and then fling myself off our one-story spec house like a virgin sacrifice and then flatten my mother’s yucca plant like a lily pad. Honestly, in hindsight, I don’t think it was the possibility of my experiencing a drug-related death that scared my mother as much as the possibility of her being known as “Mrs. Notaro, who’s addict daughter jumped off the roof” that sunk a worry knife in her straight to the bone. However, since I believed that most of the people in my environment were trying to get me to fly off a roof (that is, until I was twenty-five and finally understood that no one gives away free drugs to people they don’t know because friends always come first), I was faced with an undeniable love dilemma when I saw Mike Smithfield on the first day of middle school.

I spotted him poised at the trash can in the cafeteria, his tray held gingerly with his left hand, and I rushed over to say hi. He nodded, smiled slightly, and I gawked.

A tense, long moment passed before he said suddenly, “Um, want this Snoball?” and pointed to the pink, coconut-flecked mound that teetered on the edge of the tray, a mere millisecond away from mating with a cold, mottled Salisbury-steak patty that waited eagerly in the trash heap below. A four-star hippie dinner, I remembered thinking.

Understanding the potential of a poisoned bakery product, I was naturally wary, though the spongy, marshmallowy goodness and the fluffy-filling creaminess called out to my spiking hormones in nothing less than a siren song. No, Mike Smithfield was not my mother. That was true. But he was a lefty. An underdog. A social cripple. He understood pain, he knew it well. Those who weep are the last ones to cause a tear. I believed I could trust him. Besides, if he needed me to jump off a roof to prove my love, I would soar like an ostrich.

I nodded back and slowly looked up as I launched the Elizabeth smile, poked out my two donkey teeth, and plucked up the Snoball with my left hand. Knowing that this Snoball gift was a sure sign of tender affection, and given the fact the I was wearing my new, cute pair of brick-red Dittoes, I sucked up all of my courage in one deep breath and said, “Wanna go with me to the Sadie Hawkins dance on Friday?”

“No,” he said simply, but I didn’t believe him. I knew better. Boys will be shy. They are afraid of love, I told myself, you must coax them, show them the love light. I followed him all the way to his PE class at the gym with the Elizabeth smile frozen on my face as I asked, “Why? Why won’t you go with me? Why?” until we hit the baseball field and he just took off running. He ran the entire length of the field, constantly looking over his shoulder to see if I was still chasing him. I stood there for a long time, understanding slowly that Snoballs, although pink and soft, didn’t always mean love. At that precise moment, Patti Herman, the first girl who smoked at our school and the one most likely to force you to eat a hallucinogenic stick of Big Red in the girls’ bathroom, walked by me and said, “Hey! Do you think your pants are tight enough, Cameltoe? You don’t even need to wear pants if you’re going to show off your cookie like that!”

Things weren’t about to get better, even after that.

My romantic life took a violent turn my sophomore year in high school. I was adoringly watching Jim Kroeger, a senior, play basketball in the gym when he called my name for the first time. I turned around and flashed my biggest, brightest, newly practiced Chrissy Snow bucktoothed smile just in time for him to bounce the basketball right off my head. I got up, dazed but still smiling amid the laughter rolling in waves around me, and smiled all the way to the nurse, who looked at the round, patterned welt on my forehead and asked me if I had seizures often.

Later in high school, I dated an older, nearly high school graduate from Los Angeles whom I worked with at a Pizza D’Amore (The Pizza of Love) in the mall. With romance sparking between every dough ball and sprinkle of mozzarella, our eyes met, except the one he had that was a little bit lazy. When he pulled in front of my house that night in a green Chevy van with the windows painted black, my mother chased him away, waving a dish towel and screaming, “Put it in reverse and back it up, buddy! You’re not getting your greasy pizza paws on my kid, Mr. California!”

In college, I had enough experience that I should have taken note of the red flag when it popped up on dates, especially on the ones when the guy was already drunk when I went to pick him up. It was always a bad sign, because I figured if I had the foresight to remain sober for the most promising portion of the date, the guy should have the same kind of hope, too. One such potential mate, now referred to by friends as “The Horror of Todd,” was a guy that I met in a communications law class who was not only drunk when I went to pick him up, he was unconscious. After my pounding at the front door woke him up, he accompanied me to dinner and proceeded to eat an entire cheeseburger without the use of his hands. He would look up every now and then, his face smeared with ketchup, meat flecks, and chewed-up bits of lettuce, and simply whine at me like a hyena at a carcass.

I, on the other hand, was determined to work things out. I tried as hard as I could to pretend that everything was fine, saying things like “So, how long did it take you to make the rainbow—oh, I’m sorry, light prism—in your living room out of beer bottles?” “I think it’s fascinating that you can play every Dave Matthews song by blowing into a beer bottle,” “It takes a certain kind of talent to make a wind chime out of a beer bottle,” and “No, Todd, I really don’t think that will fit up your nose, being that it’s a beer bottle.”

I began dating another guy I met at a bar until I found him engaged in a random sex act with a teenaged dairy queen, her little red apron crumpled up at the foot of the couch, but that was really okay because I was looking for a way out ever since I found a Special Olympics medal in his room. It gave me the opportunity to return his gift of the Lego block version of the Millennium Falcon that I thought was so wacky and displayed a madcap sense of humor instead of his current stage of mental development. I finally understood that he just may not have had a serious drinking problem after all, and figured it might be a wise idea to call a lawyer and prepare for my courtroom defense. My boyfriend after that planted his seed in a uterus that wasn’t mine, and I eventually got over it by losing thirty pounds and dating his best friend, who then realized girls really grossed him out.

So I graduated from college with a degree in journalism and was ready to find my dream job at a newspaper in addition to one good man who owned his own car and was certain about his sexuality, my two new, revised qualifying criteria for a potential date.

I had the exceptional bad fortune to enter the job market at the same time the morning daily newspaper bought out the afternoon daily newspaper, merged the two, and 250 reporters and editors found themselves without employment. Though I successfully scored an interview at another small paper as an obituary writer, I eventually lost out to a former features editor with twenty years’ experience.

So I began my life as Brenda Starr, cub receptionist for a small music distributor. My friend Kate worked there in the accounting department, and mentioned that the last receptionist had been let go after she was found naked at her desk, talking to clients who didn’t actually exist. It was an easy job. I didn’t have to dress up, just remain dressed, and I was hired on the spot after I reassured the general manager that I had never heard or, most important, answered to voices that called out to me from beyond demanding that I disrobe. The job had two perks: a 25 percent employee discount on records and the option that I didn’t have to wear my Wonderbra if I didn’t want to. In fact, it was encouraged that I leave it in a drawer at home.

There were plenty of handsome boys working in the warehouse, but I figured it would be wise not to shit where I ate. Besides, the handsomest one—this guy with alluringly sensitive eyes—would barely speak to me, even though I tried desperately to impress him with my knowledge and expertise at the copy machine. I was a college graduate, after all. He had a warm smile and those incredible eyes that avoided all contact with mine, almost like I was a tick that was trying to suck out his soul with my womanly stare. I tried to break the ice one day when one of his copies jammed, so I immediately jumped up to perform surgery on the machine, successfully freeing the renegade sheet of paper. I showed him the culprit and closed up the innards, but his response was slightly less than the magnificent awe I was expecting. He looked at me for only a moment, grabbed the paper from my hand, and then fled back into the warehouse.

Kate laughed when I recounted the story later that day, and I was horrified when she pointed out a little tiny booger in my left nostril that poked its milky, wormy head out every time I exhaled. Then we met up for happy hour, and Kate bought me a drink after work, and we toasted the fact that mucus was a beautiful preventative measure to shitting where you were about to take a big bite.

Descriere

From the author of "The New York Times" bestseller "The Idiot Girls' Action-Adventure Club" comes a sidesplitting tale of trying to live a grown-up life. This story has the same zits-and-all candor and outrageous humor that made Idiot Girls an instant cult phenomenon.