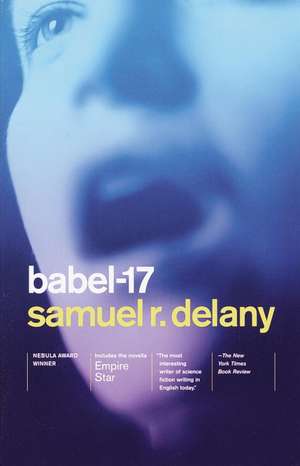

Babel-17/Empire Star

Autor Samuel R. Delanyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2001

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Nebula Awards (1966)

Babel-17, winner of the Nebula Award for best novel of the year, is a fascinating tale of a famous poet bent on deciphering a secret language that is the key to the enemy’s deadly force, a task that requires she travel with a splendidly improbable crew to the site of the next attack. For the first time, Babel-17 is published as the author intended with the short novel Empire Star, the tale of Comet Jo, a simple-minded teen thrust into a complex galaxy when he’s entrusted to carry a vital message to a distant world. Spellbinding and smart, both novels are testimony to Delany’s vast and singular talent.

Preț: 96.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 144

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.39€ • 19.20$ • 15.22£

18.39€ • 19.20$ • 15.22£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375706691

ISBN-10: 0375706690

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 131 x 205 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0375706690

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 131 x 205 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Notă biografică

Samuel R. Delany was born and raised in Harlem, where he still lives. He is a professor of English and Creative Writing at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Extras

1

It's a port city.

Here fumes rust the sky, the General thought. Industrial gases flushed the evening with oranges, salmons, purples with too much red. West, ascending and descending transports, shuttling cargoes to stellarcenters and satellites, lacerated the clouds. It's a rotten poor city too, thought the General, turning the corner by the garbage-strewn curb.

Since the Invasion six ruinous embargoes for months apiece had strangled this city whose lifeline must pulse with interstellar commerce to survive. Sequestered, how could this city exist? Six times in twenty years he'd asked himself that. Answer? It couldn't.

Panics, riots, burnings, twice cannibalism--

The General looked from the silhouetted loading-towers that jutted behind the rickety monorail to the grimy buildings. The streets were smaller here, cluttered with Transport workers, loaders, a few stellarmen in green uniforms, and the horde of pale, proper men and women who managed the intricate sprawl of customs operations. They are quiet now, intent on home or work, the General thought. Yet all these people have lived for two decades under the Invasion. They've starved during the embargoes, broken windows, looted, run screaming before firehoses, torn flesh from a corpse's arm with decalcified teeth.

Who is this animal man? He asked himself the abstract question to blur the lines of memory. It was easier, being a general, to ask about the "animal man" than about the woman who had sat in the middle of the sidewalk during the last embargo holding her skeletal baby by one leg, or the three scrawny teenage girls who had attacked him on the street with razors (--she had hissed through brown teeth, the bar of metal glistening toward his chest, "Come here, Beefsteak! Come get me, Lunch meat . . ." He had used karate--) or the blind man who had walked up the avenue, screaming.

Pale and proper men and women now, who spoke softly, who always hesitated before they let an expression fix their faces, with pale, proper, patriotic ideas: work for victory over the Invaders; Alona Star and Kip Rhyak were great in "Stellar Holliday" but Ronald Quar was the best serious actor around. They listened to Hi Lite's music (or did they listen, wondered the General, during those slow dances where no one touched). A position in Customs was a good secure job.

Working directly in Transport was probably more exciting and fun to watch in the movies; but really, such strange people--

Those with more intelligence and sophistication discussed Rydra Wong's poetry.

They spoke of the Invasion often, with some hundred phrases consecrated by twenty years' repetition on newscasts and in the papers. They referred to the embargoes seldom, and only by the one word.

Take any of them, take any million. Who are they? What do they want? What would they say if given a chance to say anything?

Rydra Wong has become this age's voice. The General recalled the glib line from a hyperbolic review. Paradoxical: a military leader with a military goal, he was going to meet Rydra Wong now.

The streetlights came on and his image glazed on the plate glass window of the bar. That's right, I'm not wearing my uniform this evening. He saw a tall, muscular man with the authority of half a century in his craggy face. He was uncomfortable in the gray civilian suit. Till age thirty, the physical impression he had left with people was "big and bumbling." Afterwards--the change had coincided with the Invasion--it was "massive and authoritarian."

Had Rydra Wong come to see him at Administrative Alliance Headquarters, he would have felt secure. But he was in civvies, not in stellarman-green. The bar was new to him. And she was the most famous poet in five explored galaxies. For the first time in a long while he felt bumbling again.

He went inside.

And whispered, "My God, she's beautiful," without even having to pick her from among the other women. "I didn't know she was so beautiful, not from the pictures . . ."

She turned to him (as the figure in the mirror behind the counter caught sight of him and turned away), stood up from the stool, smiled.

He walked forward, took her hand, the words Good evening, Miss Wong, tumbling on his tongue till he swallowed them unspoken. And now she was about to speak.

She wore copper lipstick, and the pupils of her eyes were beaten disks of copper--

"Babel-17," she said. "I haven't solved it yet, General Forester."

A knitted indigo dress, and her hair like fast water at night spilling one shoulder; he said, "That doesn't really surprise us, Miss Wong."

Surprise, he thought. She puts her hand on the bar, she leans back on the stool, hip moving in knitted blue, and with each movement, I am amazed, surprised, bewildered. Can I be this off guard, or can she really be that--

"But I've gotten further than you people at Military have been able to." The gentle line of her mouth bowed with gentler laughter.

"From what I've been led to expect of you, Miss Wong, that doesn't surprise me either." Who is she? he thought. He had asked the question of the abstract population. He had asked it of his own reflected image. He asked it of her now, thinking, No one else matters, but I must know about her. That's important. I have to know.

"First of all, General," she was saying, "Babel-17 isn't a code."

His mind skidded back to the subject and arrived teetering. "Not a code? But I thought Cryptography had at least established--" He stopped, because he wasn't sure what Cryptography had established, and because he needed another moment to haul himself down from the ledges of her high cheekbones, to retreat from the caves of her eyes. Tightening the muscles of his face, he marshaled his thoughts to Babel-17. The Invasion: Babel-17 might be one key to ending this twenty-year scourge. "You mean we've just been trying to decipher a lot of nonsense?"

"It's not a code," she repeated. "It's a language."

The General frowned. "Well, whatever you call it, code or language, we still have to figure out what it says. As long as we don't understand it, we're a hell of a way from where we should be." The exhaustion and pressure of the last months homed in his belly, a secret beast to strike the back of his tongue, harshening his words.

Her smile had left, and both hands were on the counter. He wanted to retract the harshness. She said, "You're not directly connected with the Cryptography Department." The voice was even, calming.

He shook his head.

"Then let me tell you this. Basically, General Forester, there are two types of codes, ciphers, and true codes. In the first, letters, or symbols that stand for letters, are shuffled and juggled according to a pattern. In the second, letters, words, or groups of words are replaced by other letters, symbols, or words. A code can be one type or the other, or a combination. But both have this in common: once you find the key, you just plug it in and out come logical sentences. A language, however, has its own internal logic, its own grammar, its own way of putting thoughts together with words that span various spectra of meaning. There is no key you can plug in to unlock the exact meaning. At best you can get a close approximation."

"Do you mean that Babel-17 decodes into some other language?"

"Not at all. That's the first thing I checked. We can take a probability scan on various elements and see if they are congruent with other language patterns, even if these elements are in the wrong order. No. Babel-17 is a language itself which we do not understand."

"I think--" General Forester tried to smile--"what you're trying to tell me is that because it isn't a code, but rather an alien language, we might as well give up." If this were defeat, receiving it from her was almost relief.

But she shook her head. "I'm afraid that's not what I'm saying at all. Unknown languages have been deciphered without translations, Linear B and Hittite for example. But if I'm to get further with Babel-17, I'll have to know a great deal more."

The General raised his eyebrows. "What more do you need to know? We've given you all our samples. When we get more, we'll certainly--"

"General, I have to know everything you know about Babel-17; where you got it, when, under what circumstances, anything that might give me a clue to the subject matter."

"We've released all the information that we--"

"You gave me ten pages of double-spaced typewritten garble with the code name Babel-17 and asked me what it meant. With just that I can't tell you. With more, I might. It's that simple."

He thought: If it were that simple, if it were only that simple, we would never have called you in about it, Rydra Wong.

She said: "If it were that simple, if it were only that simple, you would never have called me in about it, General Forester."

He started, for one absurd moment convinced she had read his mind. But of course, she would know that. Wouldn't she?

"General Forester, has your Cryptography Department even discovered it's a language?"

"If they have, they haven't told me."

"I'm fairly sure they don't know. I've made a few structural inroads on the grammar. Have they done that?"

"No."

"General, although they know a hell of a lot about codes, they know nothing of the nature of language. That sort of idiotic specialization is one of the reasons I haven't worked with them for the past six years."

Who is she? he thought again. A security dossier had been handed him that morning, but he had passed it to his aide and merely noted, later, that it had been marked "approved." He heard himself say, "Perhaps if you could tell me a little about yourself, Miss Wong, I could speak more freely with you." Illogical, yet he'd spoken it with measured calm and surety. Was her expression quizzical?

"What do you want to know?"

"What I already know is only this: your name, and that some time ago you worked for Military Cryptography. I know that even though you left when very young, you had enough of a reputation so that, six years later, the people who remembered you said unanimously--after they had struggled with Babel-17 for a month--'Send it to Rydra Wong.'" He paused. "And you tell me you have gotten someplace with it. So they were right."

"Let's have drinks," she said.

The bartender drifted forward, drifted back, leaving two small glasses of smoky green. She sipped, watching him. Her eyes, he thought, slant like astounded wings.

"I'm not from Earth," she said. "My father was a Communications engineer at Stellarcenter X-11-B just beyond Uranus. My mother was a translator for the Court of Outer Worlds. Until I was seven I was the spoiled brat of the Stellarcenter. There weren't many children. We moved rockside to Uranus-XXVII in '52. By the time I was twelve, I knew seven Earth languages and could make myself understood in five extraterrestrial tongues. I pick up languages like most people pick up the lyrics to popular songs. I lost both parents during the second embargo."

"You were on Uranus during the embargo?"

"You know what happened?"

"I know the Outer Planets were hit a lot harder than the Inner."

"Then you don't know. But, yes, they were." She drew a breath as memory surprised her. "One drink isn't enough to make me talk about it, though. When I came out of the hospital, there was a chance I may have had brain damage."

"Brain damage--?"

"Malnutrition you know about. Add neurosciatic plague."

"I know about plague, too."

"Anyway, I came to Earth to stay with an aunt and uncle here and receive neurotherapy. Only I didn't need it. And I don't know whether it was psychological or physiological, but I came out of the whole business with total verbal recall. I'd been bordering on it all my life so it wasn't too odd. But I also had perfect pitch."

"Doesn't that usually go along with lightning calculation and eidetic memory? I can see how all of them would be of use to a cryptographer."

"I'm a good mathematician, but no lightning calculator. I test high on visual conception and special relations--dream in technicolor and all that--but the total recall is strictly verbal. I had already begun writing. During the summer I got a job translating with the government and began to bone up on codes. In a little while I discovered that I had a certain knack. I'm not a good cryptographer. I don't have the patience to work that hard on anything written down that I didn't write myself. Neurotic as hell; that's another reason I gave it up for poetry. But the 'knack' was sort of frightening. Somehow, when I had too much work to do, and somewhere else I really wanted to be, and was scared my supervisor would start getting on my neck, suddenly everything I knew about communication would come together in my head, and it was easier to read the thing in front of me and say what it said than to be that scared and tired and miserable."

She glanced at her drink.

"Eventually the knack almost got to where I could control it. By then I was nineteen and had a reputation as the little girl who could crack anything. I guess it was knowing something about language that did it, being more facile at recognizing patterns--like distinguishing grammatical order from random rearrangement by feel, which is what I did with Babel-17."

"Why did you leave?"

"I've given you two reasons. A third is simply that when I mastered the knack, I wanted to use it for my own purposes. At nineteen, I quit the Military and, well, got . . . married, and started writing seriously. Three years later my first book came out." She shrugged, smiled. "For anything after that, read the poems. It's all there."

"And on the worlds of five galaxies, now, people delve your imagery and meaning for the answers to the riddles of language, love, and isolation." The three words jumped his sentence like vagabonds on a boxcar. She was before him, and was talking; here, divorced from the military, he felt desperately isolated; and he was desperately in . . . No!

That was impossible and ridiculous and too simple to explain what coursed and pulsed behind his eyes, inside his hands. "Another drink?" Automatic defense. But she will take it for automatic politeness. Will she? The bartender came, left.

"The worlds of five galaxies," she repeated. "That's so strange. I'm only twenty-six." Her eyes fixed somewhere behind the mirror. She was only half-through her first drink.

It's a port city.

Here fumes rust the sky, the General thought. Industrial gases flushed the evening with oranges, salmons, purples with too much red. West, ascending and descending transports, shuttling cargoes to stellarcenters and satellites, lacerated the clouds. It's a rotten poor city too, thought the General, turning the corner by the garbage-strewn curb.

Since the Invasion six ruinous embargoes for months apiece had strangled this city whose lifeline must pulse with interstellar commerce to survive. Sequestered, how could this city exist? Six times in twenty years he'd asked himself that. Answer? It couldn't.

Panics, riots, burnings, twice cannibalism--

The General looked from the silhouetted loading-towers that jutted behind the rickety monorail to the grimy buildings. The streets were smaller here, cluttered with Transport workers, loaders, a few stellarmen in green uniforms, and the horde of pale, proper men and women who managed the intricate sprawl of customs operations. They are quiet now, intent on home or work, the General thought. Yet all these people have lived for two decades under the Invasion. They've starved during the embargoes, broken windows, looted, run screaming before firehoses, torn flesh from a corpse's arm with decalcified teeth.

Who is this animal man? He asked himself the abstract question to blur the lines of memory. It was easier, being a general, to ask about the "animal man" than about the woman who had sat in the middle of the sidewalk during the last embargo holding her skeletal baby by one leg, or the three scrawny teenage girls who had attacked him on the street with razors (--she had hissed through brown teeth, the bar of metal glistening toward his chest, "Come here, Beefsteak! Come get me, Lunch meat . . ." He had used karate--) or the blind man who had walked up the avenue, screaming.

Pale and proper men and women now, who spoke softly, who always hesitated before they let an expression fix their faces, with pale, proper, patriotic ideas: work for victory over the Invaders; Alona Star and Kip Rhyak were great in "Stellar Holliday" but Ronald Quar was the best serious actor around. They listened to Hi Lite's music (or did they listen, wondered the General, during those slow dances where no one touched). A position in Customs was a good secure job.

Working directly in Transport was probably more exciting and fun to watch in the movies; but really, such strange people--

Those with more intelligence and sophistication discussed Rydra Wong's poetry.

They spoke of the Invasion often, with some hundred phrases consecrated by twenty years' repetition on newscasts and in the papers. They referred to the embargoes seldom, and only by the one word.

Take any of them, take any million. Who are they? What do they want? What would they say if given a chance to say anything?

Rydra Wong has become this age's voice. The General recalled the glib line from a hyperbolic review. Paradoxical: a military leader with a military goal, he was going to meet Rydra Wong now.

The streetlights came on and his image glazed on the plate glass window of the bar. That's right, I'm not wearing my uniform this evening. He saw a tall, muscular man with the authority of half a century in his craggy face. He was uncomfortable in the gray civilian suit. Till age thirty, the physical impression he had left with people was "big and bumbling." Afterwards--the change had coincided with the Invasion--it was "massive and authoritarian."

Had Rydra Wong come to see him at Administrative Alliance Headquarters, he would have felt secure. But he was in civvies, not in stellarman-green. The bar was new to him. And she was the most famous poet in five explored galaxies. For the first time in a long while he felt bumbling again.

He went inside.

And whispered, "My God, she's beautiful," without even having to pick her from among the other women. "I didn't know she was so beautiful, not from the pictures . . ."

She turned to him (as the figure in the mirror behind the counter caught sight of him and turned away), stood up from the stool, smiled.

He walked forward, took her hand, the words Good evening, Miss Wong, tumbling on his tongue till he swallowed them unspoken. And now she was about to speak.

She wore copper lipstick, and the pupils of her eyes were beaten disks of copper--

"Babel-17," she said. "I haven't solved it yet, General Forester."

A knitted indigo dress, and her hair like fast water at night spilling one shoulder; he said, "That doesn't really surprise us, Miss Wong."

Surprise, he thought. She puts her hand on the bar, she leans back on the stool, hip moving in knitted blue, and with each movement, I am amazed, surprised, bewildered. Can I be this off guard, or can she really be that--

"But I've gotten further than you people at Military have been able to." The gentle line of her mouth bowed with gentler laughter.

"From what I've been led to expect of you, Miss Wong, that doesn't surprise me either." Who is she? he thought. He had asked the question of the abstract population. He had asked it of his own reflected image. He asked it of her now, thinking, No one else matters, but I must know about her. That's important. I have to know.

"First of all, General," she was saying, "Babel-17 isn't a code."

His mind skidded back to the subject and arrived teetering. "Not a code? But I thought Cryptography had at least established--" He stopped, because he wasn't sure what Cryptography had established, and because he needed another moment to haul himself down from the ledges of her high cheekbones, to retreat from the caves of her eyes. Tightening the muscles of his face, he marshaled his thoughts to Babel-17. The Invasion: Babel-17 might be one key to ending this twenty-year scourge. "You mean we've just been trying to decipher a lot of nonsense?"

"It's not a code," she repeated. "It's a language."

The General frowned. "Well, whatever you call it, code or language, we still have to figure out what it says. As long as we don't understand it, we're a hell of a way from where we should be." The exhaustion and pressure of the last months homed in his belly, a secret beast to strike the back of his tongue, harshening his words.

Her smile had left, and both hands were on the counter. He wanted to retract the harshness. She said, "You're not directly connected with the Cryptography Department." The voice was even, calming.

He shook his head.

"Then let me tell you this. Basically, General Forester, there are two types of codes, ciphers, and true codes. In the first, letters, or symbols that stand for letters, are shuffled and juggled according to a pattern. In the second, letters, words, or groups of words are replaced by other letters, symbols, or words. A code can be one type or the other, or a combination. But both have this in common: once you find the key, you just plug it in and out come logical sentences. A language, however, has its own internal logic, its own grammar, its own way of putting thoughts together with words that span various spectra of meaning. There is no key you can plug in to unlock the exact meaning. At best you can get a close approximation."

"Do you mean that Babel-17 decodes into some other language?"

"Not at all. That's the first thing I checked. We can take a probability scan on various elements and see if they are congruent with other language patterns, even if these elements are in the wrong order. No. Babel-17 is a language itself which we do not understand."

"I think--" General Forester tried to smile--"what you're trying to tell me is that because it isn't a code, but rather an alien language, we might as well give up." If this were defeat, receiving it from her was almost relief.

But she shook her head. "I'm afraid that's not what I'm saying at all. Unknown languages have been deciphered without translations, Linear B and Hittite for example. But if I'm to get further with Babel-17, I'll have to know a great deal more."

The General raised his eyebrows. "What more do you need to know? We've given you all our samples. When we get more, we'll certainly--"

"General, I have to know everything you know about Babel-17; where you got it, when, under what circumstances, anything that might give me a clue to the subject matter."

"We've released all the information that we--"

"You gave me ten pages of double-spaced typewritten garble with the code name Babel-17 and asked me what it meant. With just that I can't tell you. With more, I might. It's that simple."

He thought: If it were that simple, if it were only that simple, we would never have called you in about it, Rydra Wong.

She said: "If it were that simple, if it were only that simple, you would never have called me in about it, General Forester."

He started, for one absurd moment convinced she had read his mind. But of course, she would know that. Wouldn't she?

"General Forester, has your Cryptography Department even discovered it's a language?"

"If they have, they haven't told me."

"I'm fairly sure they don't know. I've made a few structural inroads on the grammar. Have they done that?"

"No."

"General, although they know a hell of a lot about codes, they know nothing of the nature of language. That sort of idiotic specialization is one of the reasons I haven't worked with them for the past six years."

Who is she? he thought again. A security dossier had been handed him that morning, but he had passed it to his aide and merely noted, later, that it had been marked "approved." He heard himself say, "Perhaps if you could tell me a little about yourself, Miss Wong, I could speak more freely with you." Illogical, yet he'd spoken it with measured calm and surety. Was her expression quizzical?

"What do you want to know?"

"What I already know is only this: your name, and that some time ago you worked for Military Cryptography. I know that even though you left when very young, you had enough of a reputation so that, six years later, the people who remembered you said unanimously--after they had struggled with Babel-17 for a month--'Send it to Rydra Wong.'" He paused. "And you tell me you have gotten someplace with it. So they were right."

"Let's have drinks," she said.

The bartender drifted forward, drifted back, leaving two small glasses of smoky green. She sipped, watching him. Her eyes, he thought, slant like astounded wings.

"I'm not from Earth," she said. "My father was a Communications engineer at Stellarcenter X-11-B just beyond Uranus. My mother was a translator for the Court of Outer Worlds. Until I was seven I was the spoiled brat of the Stellarcenter. There weren't many children. We moved rockside to Uranus-XXVII in '52. By the time I was twelve, I knew seven Earth languages and could make myself understood in five extraterrestrial tongues. I pick up languages like most people pick up the lyrics to popular songs. I lost both parents during the second embargo."

"You were on Uranus during the embargo?"

"You know what happened?"

"I know the Outer Planets were hit a lot harder than the Inner."

"Then you don't know. But, yes, they were." She drew a breath as memory surprised her. "One drink isn't enough to make me talk about it, though. When I came out of the hospital, there was a chance I may have had brain damage."

"Brain damage--?"

"Malnutrition you know about. Add neurosciatic plague."

"I know about plague, too."

"Anyway, I came to Earth to stay with an aunt and uncle here and receive neurotherapy. Only I didn't need it. And I don't know whether it was psychological or physiological, but I came out of the whole business with total verbal recall. I'd been bordering on it all my life so it wasn't too odd. But I also had perfect pitch."

"Doesn't that usually go along with lightning calculation and eidetic memory? I can see how all of them would be of use to a cryptographer."

"I'm a good mathematician, but no lightning calculator. I test high on visual conception and special relations--dream in technicolor and all that--but the total recall is strictly verbal. I had already begun writing. During the summer I got a job translating with the government and began to bone up on codes. In a little while I discovered that I had a certain knack. I'm not a good cryptographer. I don't have the patience to work that hard on anything written down that I didn't write myself. Neurotic as hell; that's another reason I gave it up for poetry. But the 'knack' was sort of frightening. Somehow, when I had too much work to do, and somewhere else I really wanted to be, and was scared my supervisor would start getting on my neck, suddenly everything I knew about communication would come together in my head, and it was easier to read the thing in front of me and say what it said than to be that scared and tired and miserable."

She glanced at her drink.

"Eventually the knack almost got to where I could control it. By then I was nineteen and had a reputation as the little girl who could crack anything. I guess it was knowing something about language that did it, being more facile at recognizing patterns--like distinguishing grammatical order from random rearrangement by feel, which is what I did with Babel-17."

"Why did you leave?"

"I've given you two reasons. A third is simply that when I mastered the knack, I wanted to use it for my own purposes. At nineteen, I quit the Military and, well, got . . . married, and started writing seriously. Three years later my first book came out." She shrugged, smiled. "For anything after that, read the poems. It's all there."

"And on the worlds of five galaxies, now, people delve your imagery and meaning for the answers to the riddles of language, love, and isolation." The three words jumped his sentence like vagabonds on a boxcar. She was before him, and was talking; here, divorced from the military, he felt desperately isolated; and he was desperately in . . . No!

That was impossible and ridiculous and too simple to explain what coursed and pulsed behind his eyes, inside his hands. "Another drink?" Automatic defense. But she will take it for automatic politeness. Will she? The bartender came, left.

"The worlds of five galaxies," she repeated. "That's so strange. I'm only twenty-six." Her eyes fixed somewhere behind the mirror. She was only half-through her first drink.

Recenzii

“The most interesting writer of science fiction writing in English today.”–The New York Times Book Review

Descriere

Winner of the Nebula Award for best novel of the year, "Babel-17" is a fascinating tale of a famous poet bent on deciphering a secret language that is the key to the enemy's deadly force, a task that requires she travel with a splendidly improbable crew to the site of the next attack.

Premii

- Nebula Awards Winner, 1966