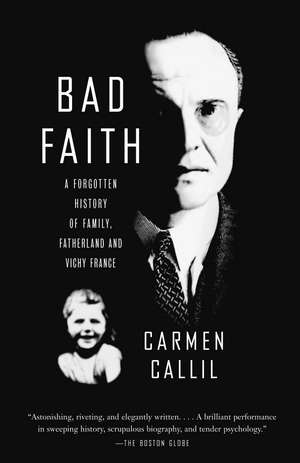

Bad Faith: A Forgotten History of Family, Fatherland and Vichy France

Autor Carmen Callilen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2007

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

National Jewish Book Award (2006)

Darquier set about to eliminate Jews in France with brutal efficiency, delivering 75,000 men, women, and children to the Nazis and confiscating Jewish property, which he used for his own gain. Carmen Callil’s riveting and sometimes darkly comic narrative reveals Darquier as a self-obsessed fantasist who found his metier in propagating hatred—a career he denied to his dying day—and traces the heartrending consequences for his daughter Anne of her poisoned family legacy. A brilliant meld of epic sweep and psychological insight, Bad Faith is a startling history of our times.

Preț: 108.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 163

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.83€ • 21.85$ • 17.34£

20.83€ • 21.85$ • 17.34£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307279255

ISBN-10: 0307279251

Pagini: 607

Ilustrații: 32 PP. PHOTOS./3 MAPS/ ILLUS.

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 34 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307279251

Pagini: 607

Ilustrații: 32 PP. PHOTOS./3 MAPS/ ILLUS.

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 34 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Carmen Callil was born in Australia and moved to England, where she began working in the publishing industry. In 1972 she founded Virago, publishing such authors as A.S. Byatt, Angela Carter, and Toni Morrison. She was subsequently Managing and Publishing Director of Chatto & Windus, publisher-atlarge for Random House UK, and Director of Channel 4 Television. The recipient of numerous honorary degrees, she is a Fellow of the Royal Society for the Arts and co-author of The Modern Library.

Extras

Chapter 1

The Priest’s Children

Cahors, in southwest France, the Darquiers’ native town, is built on a loop in the River Lot, and boasts monuments and buildings, bridges and churches of great beauty, strong red wine, plump geese and famous sons, one of whom was the great hero of the Third Republic, Léon Gambetta, after whom the main boulevard and the ancient school of Cahors are named. It is an amiable, sturdy, provincial place, with the windy beauty of so many southern French towns, dominated by its perfect medieval Pont Valentré and its Romanesque fortress of a cathedral, the massive Cathédrale de St.-Étienne. Cahors was the capital of the ancient region of Quercy, whose many rivers cut through great valleys and hills, patched with limestone plateaux, grottos and cascades. In medieval times Cahors was a flourishing city of great bankers who funded the popes and kings, but up to the Wars of Religion in the sixteenth century Quercy was also an explosive region of great violence, one explanation perhaps for the cautious politics of its citizens–Cadurciens–in the centuries that followed.

Quercy reflected an important fissure in the French body politic, in the rivalry that existed between Cahors–fiercely Catholic during the Wars of Religion, when its leaders massacred the Protestants of the town–and its southern neighbour, the more prosperous town of Montauban, a Protestant stronghold. But under Napoleon Cahors became the administrative centre of the new department of the Lot, Montauban of the Tarn-et-Garonne. (The rivalry continued: when the Vichy state came to power in 1940, and wanted to work with the Nazis to control its Jewish population, the two Frenchmen who managed much of this process were Louis Darquier of Cahors, Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, and René Bousquet of Montauban, Secretary-General for the Police.)

In the late nineteenth century the Lot was a poor agricultural department, covered with vineyards large and small, a place where “notables”–the elite bourgeoisie–reigned supreme, looking after a rural community who worked a hard land. The Lot was modestly revolutionary after 1789, restively Napoleonic under Napoleon, imperially Bonapartiste in the time of Louis Napoleon, warily republican after 1870. By 1890 the department had become solidly republican, and remained thus ever afterwards. Isolated from the political sophistications and turmoils of Paris, the Lot turned its face towards Toulouse, a hundred kilometres or so to the south.

The Lotois were conformists, but they were individualists and pragmatists. The scandalised clergy of the Lot watched as their congregations went to Mass on Sundays and holidays, while regularly voting for the godless republic and indulging in the “murderous practice” of birth control for the rest of the week. The Lot stood out in the southwest for this singularity: nearby Aveyron remained fervently Catholic; other neighbouring regions veered to the left and distanced themselves from the Church. In Cahors “On allait à l’église mais on votait à gauche”; they went to church but they voted for the left–piety on Sundays and holy days, anticlerical the rest of the week. The Lot remained faithful to both republic and Church, on its own terms. But in 1877 the vineyards which provided so much of its prosperity were destroyed by phylloxera, and so began a long decline, as the Lotois left to find work in the cities.

For the first half of his life Louis Darquier’s father, Pierre, was a fortunate man. He was born at a propitious time, he married a wealthy wife who loved him, and he had three handsome and intelligent sons, and at least one other child born out of wedlock. He was a good doctor, and almost everyone who knew him spoke well of him and remembered him fondly. Born in 1869, he was only a year old when the last of the French emperors, Louis Napoleon, Napoleon III, made the mistake of attacking Prussia in 1870. The Franco-Prussian war ended in the defeat of France and the bloody suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, and it was also the end of all kings and emperors in France. The Third Republic, proclaimed in 1870, was to last until 1940, almost the entire lifetime of Pierre Darquier.

The origins of the Darquier family were extremely modest. Louis Darquier always varied his claims to nobility, adding and subtracting claims to aristocratic, Gascon or French Celtic blood as the whim took him. His obsession with pure French blood flowing from French soil is genuine, however: most of his ancestors, the dregs of the earth for centuries, are buried in the small towns of the Lot. They were poor, and many were both illegitimate and illiterate.

Pierre Darquier was born on 23 January 1869 at number 10, rue du Tapis Vert, the street of the green carpet, one of the medieval ruelles which cluster around the Cathédrale de St.-Étienne. This was the house of his maternal great-grandmother, and generations of his family had been born and lived there. Pierre’s grandfather, Pierre Eugène Vayssade, a tobacco worker in Cahors, had died there at the age of thirty-eight. His widow, Marie Adélaide Constanty, supported herself and their only child, Eugénie, born in 1843, by working with her mother-in-law in the family’s grocery shop, which served the clergy of the cathedral nearby; it is still there on the angle of rue Nationale and place Chapou, and was worked by the family until 1907.

Pierre’s father Jean often helped his wife Eugénie and his mother-in-law at the counter, and Pierre grew up between shop and home, with his parents and grandmother, fluent in the local patois, a variant of Occitan, la langue d’Oc, the language of the Languedoc. After a lifetime’s work, Louis’ great-grandmother, when she died, had nothing to leave.

About ninety kilometres to the north of Cahors lies the medieval town of Martel, where a large number of Pierre’s paternal ancestors were born, all carefully chronicled in the records of Church and state. His great-grandfather, Bernard Avril, was a priest working in the Dordogne when he authorised the marriage of his daughter Marguerite in 1827, and agreed to provide her with an annual dowry of “wheat, half a pig, two pairs of conserved geese and twelve kilograms of nut oil.” Marguerite was twenty-three when she married Jean Joseph Darquier, a policeman from Toulouse, where his father Joseph was a cobbler and chair porter. It is necessary to be precise about these persons and dates, because it is this unfortunate Marguerite Avril who was used to give Louis Darquier his erroneous claims to nobility. Marguerite had four children, all boys, all born in Martel, before her husband Jean died at his barracks at the age of forty-five. Their first son, Jean the younger, was born in 1828, and it was he who initiated the social rise of the Darquier clan when he took up the lucrative post of tax collector.

On 25 August 1862, when he was thirty-four, Jean the tax collector married his relative Eugénie Vayssade by special dispensation, for Eugénie was also related to the fecund Father Avril. The nineteen-year-old Eugénie took her husband to live in her mother’s house in rue du Tapis Vert. There were two sons of this marriage, both called Pierre, but only the second, christened Jean Henri Pierre, survived to inherit all the considerable worldly goods garnered by his father, who died when Pierre was nineteen. Louis’ paternal grandfather the tax collector left shops in Cahors earning rent, other houses, furniture worth over twenty thousand francs, as well as letters of credit, savings, buildings, land and vineyards at Montcuq and St.-Cyprien, near Cahors.

Pierre was now a wealthy young man. He turned twenty-one just as the belle époque ushered in the joys, both frivolous and practical, of those legendary pre-war decades. As a medical student in Paris from 1888 to 1893 he and his elder brother, who died there at the age of eighteen, were the first Darquiers to savour the full glories of the Parisian vie bohème. Three years later, in 1896, he married an even wealthier young woman.

Louis Darquier’s mother, Louise, was a class above Pierre Darquier, but in fact her family’s prosperity was only one generation older than that of her husband. The Laytou family had lived in Cahors for generations, and Louise’s grandfather made their fortune with his printing works and the newspaper he founded in 1861, the Journal du Lot. His son inherited the business, and his daughter Louise Emilie Victoria was born on 11 April 1877. Like Pierre Darquier, her only sibling, a brother, also died, so she alone inherited all the wealth and property of her printing family.

Cahors was a bustling provincial city of some twenty thousand persons in January 1896, when Pierre and Louise married. He was almost twenty-seven, she eighteen; they honeymooned in Paris, Nice and Marseille. By then he had completed his medical studies in Paris at the time of the great French medical teacher and neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Pierre’s thesis, which qualified him as a doctor, was on the subject of one of Charcot’s neurological discoveries. Pierre seems to have taken the best from Charcot, unaffected by the latter’s theories of racial inheritance, and he was often described as a gifted practician, always as a kindly one. Louise Laytou brought wealth to her marriage, and was thought to have married beneath her, but in return Pierre Darquier’s profession qualified him to become one of the leading notables of Cahors and the Lot.

Pierre was blue-eyed and not tall–Louise was taller than he–and had inherited the tendency to corpulence of his mother and grandmother.

When young he was a handsome fellow with brown curls and a round, cheerful face, the shape of which, if not the temperament it expressed, was passed on to his second son, Louis, his granddaughter Anne and many of his other grandchildren. He had a rather feminine voice, wore the formal clothes of the time–bowler hat in winter, frock-coat, necktie, a boater in summer–and a handsome handlebar moustache at all times. His personal appearance, however, does not explain his success with the opposite sex.

Pierre cherished his wife, but he was a creature of his time, as addicted to dalliance as was Marshal Pétain, thirteen years his senior but a product of the same sexual mores. Pierre was a jolly man, self-indulgent, a typical “hearty bourgeois of the period, a woman-chaser, and a doctor in his spare time.” He was “big and solid, cordial and joyous, much loved in Cahors,” and was often spotted, braces flying, returning home at the crack of dawn. One early morning a worker called after him, “Hey, Doctor, do you take your trousers off to examine your patients?” But this shocked no one in those days, least of all Louise. Her “real Don Juan . . . has the charm of a Marquis,” she would say with pride. “One must know when to shut one’s eyes.”

Louise Darquier was beautiful when young, and remained so all her life. She was attended by the consideration such women are accustomed to receive, but this was not, in her case, always accompanied by much affection. Louise was “impeccable,” with “l’air presque aristocratique”–an almost aristocratic air. To some she seemed warm and lovable, to others she gushed and fluttered. Some who worked for her loved her for her kindness and affection, others regarded it as mannered patronage. Family recollections describe her as remarkably stupid, and acquaintances are not much kinder–she was “very proud,” “very spoiled, very old France, very beautiful,” “with a high, studied voice, given to little exclamations.” Everything about her was exquisite, her clothes, her hats, her considerable collection of jewellery, her carefully coiffed fair hair. Even her handkerchiefs, delicately embroidered by herself, were the envy of the women of Cahors.

Louise enjoyed ill health, feminine maladies and exercising Christian charity towards the unfortunate. She took the waters at Vichy, read poetry, wrote to her women friends, stitched and embroidered beautifully–for herself, for the church, for family and friends–and trained her maids and poor relations to look after her properly. Her letters–outpourings of domestic fuss and bother, alternating wheedling requests with woes plaintively enumerated–throb with her anxious hold on social position. She bequeathed her habitual note of lamentation to Louis, together with her pretension to social grandeur. Louis spent much of his adult life complaining that his parents did not support him, did not help him financially as they did his brothers, and when the time came, during the Occupation, that he could support himself, he made the same complaints about Pétain and the mandarins of Vichy.

Louise was what they called “une punaise de sacristie,” a churchy woman. The French Church had been in a state of recurrent war with the anti-clerical republic since the Revolution–it was Gambetta who had said in 1877 that “Le cléricalisme, c’est l’ennemi!” The Darquier marriage perfectly encapsulated this French duality. Educated at the convent of Les Dames de Nevers in Cahors, Louise went to Mass every Sunday and often during the week, while Pierre confined his attendances to weddings and funerals. Louise Darquier embodied every reason why French women were not to receive the vote until 1944.

In the early years of the Darquier marriage the struggle between the French Church and the republican government reached its climax over the Dreyfus affair and the control of education. The outcome was the separation of Church and state in 1905, the removal of education from clerical hands and the expulsion from France of a number of religious orders. The republic, ruled by governments of the Radical Party, formed in 1901 and representative of the politics of the provinces and the petite bourgeoisie, thus won its major victory over the Catholic Church in France.

The men who represented the Lot politically, at both national and local levels, were almost always lawyers and doctors, rarely the nobility, and of these doctors were always the most numerous. Pierre Darquier had wealth, the right profession, family connections and a family newspaper. He joined the Radical Party and proceeded in the classic manner: first mayor, then councillor for the department–after that would follow Paris and national politics.

His party, which would be dominant in French politics until the Second World War, was by no means radical in the British sense of the word. It was a centrist party, republican, anticlerical, but moderate–like the Whigs in England. The Radical Party was an umbrella group of many different opinions and cliques, tolerant of considerable dissent. In the Lot, Radicals often belonged to the Radical-Socialist wing of the party, the use of the word “socialist” being even more baffling to Anglo-Saxon ears, for these politicians ran the Lot like a private business. The ruling Radicals were progressive but fatherly, almost feudal men of position and profession, manipulators of influence and patronage and accustomed to being obeyed.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Priest’s Children

Cahors, in southwest France, the Darquiers’ native town, is built on a loop in the River Lot, and boasts monuments and buildings, bridges and churches of great beauty, strong red wine, plump geese and famous sons, one of whom was the great hero of the Third Republic, Léon Gambetta, after whom the main boulevard and the ancient school of Cahors are named. It is an amiable, sturdy, provincial place, with the windy beauty of so many southern French towns, dominated by its perfect medieval Pont Valentré and its Romanesque fortress of a cathedral, the massive Cathédrale de St.-Étienne. Cahors was the capital of the ancient region of Quercy, whose many rivers cut through great valleys and hills, patched with limestone plateaux, grottos and cascades. In medieval times Cahors was a flourishing city of great bankers who funded the popes and kings, but up to the Wars of Religion in the sixteenth century Quercy was also an explosive region of great violence, one explanation perhaps for the cautious politics of its citizens–Cadurciens–in the centuries that followed.

Quercy reflected an important fissure in the French body politic, in the rivalry that existed between Cahors–fiercely Catholic during the Wars of Religion, when its leaders massacred the Protestants of the town–and its southern neighbour, the more prosperous town of Montauban, a Protestant stronghold. But under Napoleon Cahors became the administrative centre of the new department of the Lot, Montauban of the Tarn-et-Garonne. (The rivalry continued: when the Vichy state came to power in 1940, and wanted to work with the Nazis to control its Jewish population, the two Frenchmen who managed much of this process were Louis Darquier of Cahors, Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, and René Bousquet of Montauban, Secretary-General for the Police.)

In the late nineteenth century the Lot was a poor agricultural department, covered with vineyards large and small, a place where “notables”–the elite bourgeoisie–reigned supreme, looking after a rural community who worked a hard land. The Lot was modestly revolutionary after 1789, restively Napoleonic under Napoleon, imperially Bonapartiste in the time of Louis Napoleon, warily republican after 1870. By 1890 the department had become solidly republican, and remained thus ever afterwards. Isolated from the political sophistications and turmoils of Paris, the Lot turned its face towards Toulouse, a hundred kilometres or so to the south.

The Lotois were conformists, but they were individualists and pragmatists. The scandalised clergy of the Lot watched as their congregations went to Mass on Sundays and holidays, while regularly voting for the godless republic and indulging in the “murderous practice” of birth control for the rest of the week. The Lot stood out in the southwest for this singularity: nearby Aveyron remained fervently Catholic; other neighbouring regions veered to the left and distanced themselves from the Church. In Cahors “On allait à l’église mais on votait à gauche”; they went to church but they voted for the left–piety on Sundays and holy days, anticlerical the rest of the week. The Lot remained faithful to both republic and Church, on its own terms. But in 1877 the vineyards which provided so much of its prosperity were destroyed by phylloxera, and so began a long decline, as the Lotois left to find work in the cities.

For the first half of his life Louis Darquier’s father, Pierre, was a fortunate man. He was born at a propitious time, he married a wealthy wife who loved him, and he had three handsome and intelligent sons, and at least one other child born out of wedlock. He was a good doctor, and almost everyone who knew him spoke well of him and remembered him fondly. Born in 1869, he was only a year old when the last of the French emperors, Louis Napoleon, Napoleon III, made the mistake of attacking Prussia in 1870. The Franco-Prussian war ended in the defeat of France and the bloody suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, and it was also the end of all kings and emperors in France. The Third Republic, proclaimed in 1870, was to last until 1940, almost the entire lifetime of Pierre Darquier.

The origins of the Darquier family were extremely modest. Louis Darquier always varied his claims to nobility, adding and subtracting claims to aristocratic, Gascon or French Celtic blood as the whim took him. His obsession with pure French blood flowing from French soil is genuine, however: most of his ancestors, the dregs of the earth for centuries, are buried in the small towns of the Lot. They were poor, and many were both illegitimate and illiterate.

Pierre Darquier was born on 23 January 1869 at number 10, rue du Tapis Vert, the street of the green carpet, one of the medieval ruelles which cluster around the Cathédrale de St.-Étienne. This was the house of his maternal great-grandmother, and generations of his family had been born and lived there. Pierre’s grandfather, Pierre Eugène Vayssade, a tobacco worker in Cahors, had died there at the age of thirty-eight. His widow, Marie Adélaide Constanty, supported herself and their only child, Eugénie, born in 1843, by working with her mother-in-law in the family’s grocery shop, which served the clergy of the cathedral nearby; it is still there on the angle of rue Nationale and place Chapou, and was worked by the family until 1907.

Pierre’s father Jean often helped his wife Eugénie and his mother-in-law at the counter, and Pierre grew up between shop and home, with his parents and grandmother, fluent in the local patois, a variant of Occitan, la langue d’Oc, the language of the Languedoc. After a lifetime’s work, Louis’ great-grandmother, when she died, had nothing to leave.

About ninety kilometres to the north of Cahors lies the medieval town of Martel, where a large number of Pierre’s paternal ancestors were born, all carefully chronicled in the records of Church and state. His great-grandfather, Bernard Avril, was a priest working in the Dordogne when he authorised the marriage of his daughter Marguerite in 1827, and agreed to provide her with an annual dowry of “wheat, half a pig, two pairs of conserved geese and twelve kilograms of nut oil.” Marguerite was twenty-three when she married Jean Joseph Darquier, a policeman from Toulouse, where his father Joseph was a cobbler and chair porter. It is necessary to be precise about these persons and dates, because it is this unfortunate Marguerite Avril who was used to give Louis Darquier his erroneous claims to nobility. Marguerite had four children, all boys, all born in Martel, before her husband Jean died at his barracks at the age of forty-five. Their first son, Jean the younger, was born in 1828, and it was he who initiated the social rise of the Darquier clan when he took up the lucrative post of tax collector.

On 25 August 1862, when he was thirty-four, Jean the tax collector married his relative Eugénie Vayssade by special dispensation, for Eugénie was also related to the fecund Father Avril. The nineteen-year-old Eugénie took her husband to live in her mother’s house in rue du Tapis Vert. There were two sons of this marriage, both called Pierre, but only the second, christened Jean Henri Pierre, survived to inherit all the considerable worldly goods garnered by his father, who died when Pierre was nineteen. Louis’ paternal grandfather the tax collector left shops in Cahors earning rent, other houses, furniture worth over twenty thousand francs, as well as letters of credit, savings, buildings, land and vineyards at Montcuq and St.-Cyprien, near Cahors.

Pierre was now a wealthy young man. He turned twenty-one just as the belle époque ushered in the joys, both frivolous and practical, of those legendary pre-war decades. As a medical student in Paris from 1888 to 1893 he and his elder brother, who died there at the age of eighteen, were the first Darquiers to savour the full glories of the Parisian vie bohème. Three years later, in 1896, he married an even wealthier young woman.

Louis Darquier’s mother, Louise, was a class above Pierre Darquier, but in fact her family’s prosperity was only one generation older than that of her husband. The Laytou family had lived in Cahors for generations, and Louise’s grandfather made their fortune with his printing works and the newspaper he founded in 1861, the Journal du Lot. His son inherited the business, and his daughter Louise Emilie Victoria was born on 11 April 1877. Like Pierre Darquier, her only sibling, a brother, also died, so she alone inherited all the wealth and property of her printing family.

Cahors was a bustling provincial city of some twenty thousand persons in January 1896, when Pierre and Louise married. He was almost twenty-seven, she eighteen; they honeymooned in Paris, Nice and Marseille. By then he had completed his medical studies in Paris at the time of the great French medical teacher and neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Pierre’s thesis, which qualified him as a doctor, was on the subject of one of Charcot’s neurological discoveries. Pierre seems to have taken the best from Charcot, unaffected by the latter’s theories of racial inheritance, and he was often described as a gifted practician, always as a kindly one. Louise Laytou brought wealth to her marriage, and was thought to have married beneath her, but in return Pierre Darquier’s profession qualified him to become one of the leading notables of Cahors and the Lot.

Pierre was blue-eyed and not tall–Louise was taller than he–and had inherited the tendency to corpulence of his mother and grandmother.

When young he was a handsome fellow with brown curls and a round, cheerful face, the shape of which, if not the temperament it expressed, was passed on to his second son, Louis, his granddaughter Anne and many of his other grandchildren. He had a rather feminine voice, wore the formal clothes of the time–bowler hat in winter, frock-coat, necktie, a boater in summer–and a handsome handlebar moustache at all times. His personal appearance, however, does not explain his success with the opposite sex.

Pierre cherished his wife, but he was a creature of his time, as addicted to dalliance as was Marshal Pétain, thirteen years his senior but a product of the same sexual mores. Pierre was a jolly man, self-indulgent, a typical “hearty bourgeois of the period, a woman-chaser, and a doctor in his spare time.” He was “big and solid, cordial and joyous, much loved in Cahors,” and was often spotted, braces flying, returning home at the crack of dawn. One early morning a worker called after him, “Hey, Doctor, do you take your trousers off to examine your patients?” But this shocked no one in those days, least of all Louise. Her “real Don Juan . . . has the charm of a Marquis,” she would say with pride. “One must know when to shut one’s eyes.”

Louise Darquier was beautiful when young, and remained so all her life. She was attended by the consideration such women are accustomed to receive, but this was not, in her case, always accompanied by much affection. Louise was “impeccable,” with “l’air presque aristocratique”–an almost aristocratic air. To some she seemed warm and lovable, to others she gushed and fluttered. Some who worked for her loved her for her kindness and affection, others regarded it as mannered patronage. Family recollections describe her as remarkably stupid, and acquaintances are not much kinder–she was “very proud,” “very spoiled, very old France, very beautiful,” “with a high, studied voice, given to little exclamations.” Everything about her was exquisite, her clothes, her hats, her considerable collection of jewellery, her carefully coiffed fair hair. Even her handkerchiefs, delicately embroidered by herself, were the envy of the women of Cahors.

Louise enjoyed ill health, feminine maladies and exercising Christian charity towards the unfortunate. She took the waters at Vichy, read poetry, wrote to her women friends, stitched and embroidered beautifully–for herself, for the church, for family and friends–and trained her maids and poor relations to look after her properly. Her letters–outpourings of domestic fuss and bother, alternating wheedling requests with woes plaintively enumerated–throb with her anxious hold on social position. She bequeathed her habitual note of lamentation to Louis, together with her pretension to social grandeur. Louis spent much of his adult life complaining that his parents did not support him, did not help him financially as they did his brothers, and when the time came, during the Occupation, that he could support himself, he made the same complaints about Pétain and the mandarins of Vichy.

Louise was what they called “une punaise de sacristie,” a churchy woman. The French Church had been in a state of recurrent war with the anti-clerical republic since the Revolution–it was Gambetta who had said in 1877 that “Le cléricalisme, c’est l’ennemi!” The Darquier marriage perfectly encapsulated this French duality. Educated at the convent of Les Dames de Nevers in Cahors, Louise went to Mass every Sunday and often during the week, while Pierre confined his attendances to weddings and funerals. Louise Darquier embodied every reason why French women were not to receive the vote until 1944.

In the early years of the Darquier marriage the struggle between the French Church and the republican government reached its climax over the Dreyfus affair and the control of education. The outcome was the separation of Church and state in 1905, the removal of education from clerical hands and the expulsion from France of a number of religious orders. The republic, ruled by governments of the Radical Party, formed in 1901 and representative of the politics of the provinces and the petite bourgeoisie, thus won its major victory over the Catholic Church in France.

The men who represented the Lot politically, at both national and local levels, were almost always lawyers and doctors, rarely the nobility, and of these doctors were always the most numerous. Pierre Darquier had wealth, the right profession, family connections and a family newspaper. He joined the Radical Party and proceeded in the classic manner: first mayor, then councillor for the department–after that would follow Paris and national politics.

His party, which would be dominant in French politics until the Second World War, was by no means radical in the British sense of the word. It was a centrist party, republican, anticlerical, but moderate–like the Whigs in England. The Radical Party was an umbrella group of many different opinions and cliques, tolerant of considerable dissent. In the Lot, Radicals often belonged to the Radical-Socialist wing of the party, the use of the word “socialist” being even more baffling to Anglo-Saxon ears, for these politicians ran the Lot like a private business. The ruling Radicals were progressive but fatherly, almost feudal men of position and profession, manipulators of influence and patronage and accustomed to being obeyed.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Astonishing, riveting, and elegantly written. . . . A brilliant performance in sweeping history, scrupulous biography, and tender psychology.” —The Boston Globe“Darquier [was] one of the monsters of French history. . . . [Callil’s] account of France’s descent into the anti-Semitic maelstrom is dramatic.” —The New York Times Book Review“Callil has written a fascinating book about this monster. . . . Bad Faith is an often moving book, as well as an improbably funny one—a study of awfulness made unexpectedly poignant by the author’s own stake in the subject.” —Harper’s“Much more than the story of one family’s dark secrets. This book becomes a quietly devastating history of Vichy France’s anti-Semitic machinations.” —The New York Times

Premii

- National Jewish Book Award Finalist, 2006