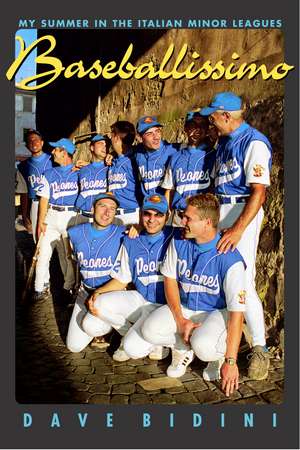

Baseballissimo

Autor Dave Bidinien Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2005

For six months Bidini followed the fortunes of the Serie B Peones, Nettunese to the core. At the same time he was also learning about his own heritage, having spent his youth vigorously ignoring his Italianness. The result of his summer in Italy is vintage Bidini: a funny, perceptive, and engrossing book that takes readers far beyond the professional sport to the game that people around the world love to play.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 94.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.10€ • 18.95$ • 14.98£

18.10€ • 18.95$ • 14.98£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771014628

ISBN-10: 0771014627

Pagini: 360

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 169 x 230 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771014627

Pagini: 360

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 169 x 230 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Author and musician Dave Bidini is the only person to have been nominated for a Gemini, Genie and Juno as well CBC's Canada Reads. A founding member of Rheostatics, he has written 10 books, including On a Cold Road, Tropic of Hockey, Around the World in 57 1/2 Gigs, and Home and Away. He has made two Gemini Award-nominated documentaries and his play, the Five Hole Stories, was staged by One Yellow Rabbit Performance Company, touring the country in 2008. His third book, Baseballissimo, is being developed for the screen by Jay Baruchel, and, in 2010, he won his third National Magazine Award, for "Travels in Narnia." He writes a weekly column for the Saturday Post and, in 2011, he published his latest book, Writing Gordon Lightfoot.

Extras

During a pregame workout in Nettuno, Italy, Mirko Rocchetti, an infielder with the Peones, arrived at the park carrying a tray of cornetti, brioche, and biscotti. Simone Cancelli (the Natural) followed twenty minutes later with a large box, which he placed on the ledge of the dugout. He lifted the lid, pulled back a layer of crepe paper, and revealed a small mountain of fresh croissants, their light, flaky shells embossed with vanilla crema. A few minutes later Francesco “Pompo” Pompozzi, the Peones’ twentyoneyearold fireballer, produced two green bottles filled with sugarsoaked espresso, and passed out little white plastic cups. Ricky Viccaro (Solid Gold) — who looked, as always, as if he were standing in front of a wind machine — showed up a halfhour into the game, swinging a red Thermos of espresso, which he cracked in the fifth inning and refilled for the beginning of the second game. Someone else placed boxes of sweets on racks above the bench, and they were polished off in no time.

This sugar fiesta was typical for the Peones, Nettuno’s Serie B baseball team. They believed — as did many Italians — that sugar and coffee were all you needed to get you through any game. Andrea Cancelli (the Emperor) munched on energy pills that tasted like tiny soap cakes. At a game in Sardinia, I saw Fabio Giolitti (Fab Julie) pat his rumbling stomach before fetching a box of wafer cookies from his kit bag, which he passed out, two at a time, to his teammates. Then Mirko asked me, “Davide? Are you hungry?” and promptly handed me two panini spread with grape jelly — the Italian athlete’s equivalent of an energy bar. At the same game, Mario Mazza, the Peones’ second baseman, gathered the team excitedly, as if he’d just cracked the opposing team’s sequence of signs, only to pass out packets of sugar he’d swiped from a café. The players poured them down the hatch. I joined in, even though I wasn’t playing, just watching the Peones, the team I’d come to Italy to write about.

I found language as much a cultural divide as the approach to food, though I was able to find my place among the Peones by spouting a combination ItaloCanadianBaseballese, at the risk of becoming Team Stooge. At times, I wondered whether the boys were asking me questions just to see how I would mangle their mother tongue.

One day, Chencho Navacci, the team’s lefthanded reliever, heard me comment that a hit had been “il pollo morto.”

“Tuo pollo?” he asked.

“No, la palla. La palla è il pollo. Il pollo è morto.”

“Okay, okay,” he said, smiling.

“You know, dying quail,” I said, reverting to English.

“?”

“The chicken is dead,” I said, making a high, curving motion with my hand. “The ball — la palla. La palla è il pollo.”

“Il pollo?”

I couldn’t understand why Chencho was so confused. I’d always assumed that dying quail — baseball’s term for a hit that bloops between the infield and the outfield — was one of those universal baseball terms.

“Si! Il pollo è morto!” I repeated.

“Il pollo è morto? Okay, is good!” he said, turning away.

Later, I told Janet, my wife, what had happened at the ballpark.

“La qualia,” she corrected. “You should have said ‘la qualia.’”

“How was I supposed to know they had quail in Italy?”

“What did you think? They have chicken, don’t they?”

“Ya, but quail.”

“Yes, quail. And I don’t think pollo is the right word for chicken. La gallina is how you say chicken. Pollo is what you order in a restaurant.’

“Pollo is restaurant chicken?” I said, mortified.

“I think so.”

“So, you mean I was telling Chencho that the ball was like a piece of cooked chicken?”

“Yes, I’m afraid you were.”

“Flying cooked chicken?”

For my first few weeks with the team, I probably sounded like a moron. I regularly confused the word for last with first, and used always instead of never, as in “Speaking good Italian is always the first thing I learn.” I’d also fallen into the embarrassing habit of pronouncing the word penne (the pasta) as if it were pene, the Italian word for penis. But I was excused for saying things like “I’d like my penis with tomatoes and mushroom,” and, to their credit, the team and townsfolk hung with me. After a while, the players must have noticed a pattern in the things I said at practice: dying quail, rabbit ball, hot potato, ducks on the pond, bring the gas, in his kitchen. They probably figured I was just really hungry.

Before leaving Canada for Italy in the spring of 2002, I bound my five bats together with black packing tape. They looked like a wooden bouquet and their heads clacked as I laid them on the airport’s baggage belt: the brown, thirtyfourounce Harold Baines Adirondack, two new fungo bats, a red Louisville smiting pole, and a vintage Pudge Fisk hurt stick, with Pudge’s signature burnt into the fat of the wood.

My bats and I weren’t alone. There was also my wife, Janet; our two children, Cecilia, a curlyhaired twoyearold blabberpuss, and Lorenzo, not ten weeks old; and for the first part of the trip Janet’s mother, Norma.

Other than a curiosity to experience sport unblemished by money, I had a few more reasons for shipping the family off to Italy. First, I love the game of baseball, having committed the last halfdecade of summer Sunday evenings to something named the Queen Street Softball League. I am the starting shortstop for a team called the Rebels, originally affiliated with a local brewery, which was both our strength and poison. I spend most games standing on the gravel in my white Converse lowcuts, waiting for some silkscreen print shop worker or bartender or anthropology student or recordstore clerk to whale the ball to my feet, providing that no offleash hound makes for the pitcher’s mound, lovestruck couple promenades through centre field, or rapscallions riding their bmxs rip up the sod in the power alleys, which lie just to the right of the oak tree and slightly to the left of the guy selling weed out of his Dickie Dee icecream cart. Still, we compete like heck. As a weekend scrub, I give everything at the plate. I also try my best to keep my feet spread, arse down, and eyes on the ball when fielding ground hops, the way Pee Wee Reese might have. Statswise, I’ve hovered around .400 — a modest softball average — year in and out, having effectively learned how to slice a 25-mph spinball just beyond the reach of the guy in the knee brace, who’s swatting a mosquito while trying not to spill his lager.

It’s because of my shortcomings as a ballplayer that I couldn’t possibly have tagged along with an elite, or even semielite, prolevel team in Italy. I had briefly flirted with the notion of following around a major league club, but ditched the idea after hearing about Nettuno, which had just the right combination of respectable talent level, rabid fan base, and casual sporting culture to allow a dreamy scrub like me to toss in my glove and wander among them.

Which is to say: they let me.

From the Hardcover edition.

This sugar fiesta was typical for the Peones, Nettuno’s Serie B baseball team. They believed — as did many Italians — that sugar and coffee were all you needed to get you through any game. Andrea Cancelli (the Emperor) munched on energy pills that tasted like tiny soap cakes. At a game in Sardinia, I saw Fabio Giolitti (Fab Julie) pat his rumbling stomach before fetching a box of wafer cookies from his kit bag, which he passed out, two at a time, to his teammates. Then Mirko asked me, “Davide? Are you hungry?” and promptly handed me two panini spread with grape jelly — the Italian athlete’s equivalent of an energy bar. At the same game, Mario Mazza, the Peones’ second baseman, gathered the team excitedly, as if he’d just cracked the opposing team’s sequence of signs, only to pass out packets of sugar he’d swiped from a café. The players poured them down the hatch. I joined in, even though I wasn’t playing, just watching the Peones, the team I’d come to Italy to write about.

I found language as much a cultural divide as the approach to food, though I was able to find my place among the Peones by spouting a combination ItaloCanadianBaseballese, at the risk of becoming Team Stooge. At times, I wondered whether the boys were asking me questions just to see how I would mangle their mother tongue.

One day, Chencho Navacci, the team’s lefthanded reliever, heard me comment that a hit had been “il pollo morto.”

“Tuo pollo?” he asked.

“No, la palla. La palla è il pollo. Il pollo è morto.”

“Okay, okay,” he said, smiling.

“You know, dying quail,” I said, reverting to English.

“?”

“The chicken is dead,” I said, making a high, curving motion with my hand. “The ball — la palla. La palla è il pollo.”

“Il pollo?”

I couldn’t understand why Chencho was so confused. I’d always assumed that dying quail — baseball’s term for a hit that bloops between the infield and the outfield — was one of those universal baseball terms.

“Si! Il pollo è morto!” I repeated.

“Il pollo è morto? Okay, is good!” he said, turning away.

Later, I told Janet, my wife, what had happened at the ballpark.

“La qualia,” she corrected. “You should have said ‘la qualia.’”

“How was I supposed to know they had quail in Italy?”

“What did you think? They have chicken, don’t they?”

“Ya, but quail.”

“Yes, quail. And I don’t think pollo is the right word for chicken. La gallina is how you say chicken. Pollo is what you order in a restaurant.’

“Pollo is restaurant chicken?” I said, mortified.

“I think so.”

“So, you mean I was telling Chencho that the ball was like a piece of cooked chicken?”

“Yes, I’m afraid you were.”

“Flying cooked chicken?”

For my first few weeks with the team, I probably sounded like a moron. I regularly confused the word for last with first, and used always instead of never, as in “Speaking good Italian is always the first thing I learn.” I’d also fallen into the embarrassing habit of pronouncing the word penne (the pasta) as if it were pene, the Italian word for penis. But I was excused for saying things like “I’d like my penis with tomatoes and mushroom,” and, to their credit, the team and townsfolk hung with me. After a while, the players must have noticed a pattern in the things I said at practice: dying quail, rabbit ball, hot potato, ducks on the pond, bring the gas, in his kitchen. They probably figured I was just really hungry.

Before leaving Canada for Italy in the spring of 2002, I bound my five bats together with black packing tape. They looked like a wooden bouquet and their heads clacked as I laid them on the airport’s baggage belt: the brown, thirtyfourounce Harold Baines Adirondack, two new fungo bats, a red Louisville smiting pole, and a vintage Pudge Fisk hurt stick, with Pudge’s signature burnt into the fat of the wood.

My bats and I weren’t alone. There was also my wife, Janet; our two children, Cecilia, a curlyhaired twoyearold blabberpuss, and Lorenzo, not ten weeks old; and for the first part of the trip Janet’s mother, Norma.

Other than a curiosity to experience sport unblemished by money, I had a few more reasons for shipping the family off to Italy. First, I love the game of baseball, having committed the last halfdecade of summer Sunday evenings to something named the Queen Street Softball League. I am the starting shortstop for a team called the Rebels, originally affiliated with a local brewery, which was both our strength and poison. I spend most games standing on the gravel in my white Converse lowcuts, waiting for some silkscreen print shop worker or bartender or anthropology student or recordstore clerk to whale the ball to my feet, providing that no offleash hound makes for the pitcher’s mound, lovestruck couple promenades through centre field, or rapscallions riding their bmxs rip up the sod in the power alleys, which lie just to the right of the oak tree and slightly to the left of the guy selling weed out of his Dickie Dee icecream cart. Still, we compete like heck. As a weekend scrub, I give everything at the plate. I also try my best to keep my feet spread, arse down, and eyes on the ball when fielding ground hops, the way Pee Wee Reese might have. Statswise, I’ve hovered around .400 — a modest softball average — year in and out, having effectively learned how to slice a 25-mph spinball just beyond the reach of the guy in the knee brace, who’s swatting a mosquito while trying not to spill his lager.

It’s because of my shortcomings as a ballplayer that I couldn’t possibly have tagged along with an elite, or even semielite, prolevel team in Italy. I had briefly flirted with the notion of following around a major league club, but ditched the idea after hearing about Nettuno, which had just the right combination of respectable talent level, rabid fan base, and casual sporting culture to allow a dreamy scrub like me to toss in my glove and wander among them.

Which is to say: they let me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

Nettuno Peones, 2002

Stronzo with a Smiting Pole

The Pasta Ghetto

Bob Dylan and the Drag Bunt

Mia Palanca, Mia

Nettuno at Montefiascone

There Came a One-Armed Man

1975

Roma at Nettuno

A Pocket of Brick and Mortar

1985

Nettuno at Salerno

Nettuno at Sardinia

Baseball in the Jaws of War

The Eye of the Pig

Montefiascone at Nettuno

The Music of the Mound

Father Baseball

The Fires of Rome

1987

The Eternal Game

Nettuno at Roma

Mike the Duck Must Die

Salerno at Nettuno

1992

The Italian

Palermo at Nettuno

If They Don’t Win, It’s a Shame

The Night of the Wolves

Coming Home

Baseballissimo

Epilogue: A Play at the Plate

Acknowledgments

From the Hardcover edition.

Stronzo with a Smiting Pole

The Pasta Ghetto

Bob Dylan and the Drag Bunt

Mia Palanca, Mia

Nettuno at Montefiascone

There Came a One-Armed Man

1975

Roma at Nettuno

A Pocket of Brick and Mortar

1985

Nettuno at Salerno

Nettuno at Sardinia

Baseball in the Jaws of War

The Eye of the Pig

Montefiascone at Nettuno

The Music of the Mound

Father Baseball

The Fires of Rome

1987

The Eternal Game

Nettuno at Roma

Mike the Duck Must Die

Salerno at Nettuno

1992

The Italian

Palermo at Nettuno

If They Don’t Win, It’s a Shame

The Night of the Wolves

Coming Home

Baseballissimo

Epilogue: A Play at the Plate

Acknowledgments

From the Hardcover edition.