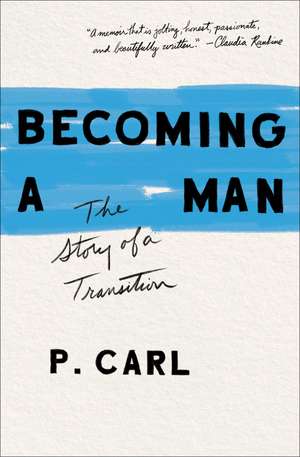

Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition

Autor P. Carlen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2021

Becoming a Man is a “moving narrative [that] illuminates the joy, courage, necessity, and risk-taking of gender transition” (Kirkus Reviews). For fifty years P. Carl lived as a girl and then as a queer woman, building a career, a life, and a loving marriage, yet still waiting to realize himself in full. As Carl embarks on his gender transition, he takes us inside the complex shifts and questions that arise throughout—the alternating moments of arrival and estrangement. He writes intimately about how transitioning reconfigures both his own inner experience and his closest bonds—his twenty-year relationship with his wife, Lynette; his already tumultuous relationships with his parents; and seemingly solid friendships that are subtly altered, often painfully and wordlessly.

Carl “has written a poignant and candid self-appraisal of life as a ‘work-of-progress’” (Booklist) and blends the remarkable story of his own personal journey with incisive cultural commentary, writing beautifully about gender, power, and inequality in America. His transition occurs amid the rise of the Trump administration and the #MeToo movement—a transition point in America’s own story, when transphobia and toxic masculinity are under fire even as they thrive in the highest halls of power. Carl’s quest to become himself and to reckon with his masculinity mirrors, in many ways, the challenge before the country as a whole, to imagine a society where every member can have a vibrant, livable life. Here, through this brave and deeply personal work, Carl brings an unparalleled new voice to this conversation.

Preț: 94.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.07€ • 18.80$ • 14.92£

18.07€ • 18.80$ • 14.92£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982105105

ISBN-10: 1982105100

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982105100

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

P. Carl is a Distinguished Artist-in-Residence at Emerson College in Boston and was awarded a 2017 Art of Change Fellowship from the Ford Foundation, the Berlin Prize fellowship from the American Academy for the Fall of 2018, the Andrew W. Mellon Creative Research Residency at the University of Washington, and the Anschutz Fellowship at Princeton for spring of 2020. He made theater for twenty years and now writes, teaches, travels, mountain climbs, and swims. He resides in Boston and lives with his wife of twenty-two years, the writer Lynette D’Amico and their dogs Lenny and Sonny. Becoming a Man is his first book.

Extras

Chapter One: Finally MeCHAPTER ONE FINALLY ME

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

When bodies gather as they do to express their indignation and to enact their plural existence in public space, they are also making broader demands; they are demanding to be recognized, to be valued, they are exercising a right to appear, to exercise freedom, and they are demanding a livable life.

—Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly

I have been living as a white, Midwestern woman for fifty years and ten months, until one weekend in March, I cross a line. It comes unexpectedly on this particular day, but I’ve been thinking and expecting it for as long as I can remember. The Hotel Chandler in Midtown Manhattan: seven months on testosterone, I check in at about 6 P.M. “Good evening, sir, how are you?” This isn’t my first “sir”—they have come and gone my entire life, and more often in recent weeks. But it’s the start of something that from this “sir” forward will be my new life. On March 16, 2017, I become a man.

What changed from yesterday and the day before yesterday? What is this fine line of gender that makes me a woman one day and a man the next? Did my jawline get just square enough, my voice deep enough? Did my hairline recede enough? All I know is that from March 16 forward, I am finally me. I take a selfie and send it to my wife, with a text message: “I’m me now.” I can’t fucking believe it. I am finally me. I am visible for the first time, just two months shy of my fifty-first birthday. This rite of passage, this moment of being welcomed into the world as embodied is something most people experience at the moment of birth, or even earlier, at the moment of those ultrasound pictures of unborn babies that all my friends with children have, already sexed by their obstetrician and their parents. Some of us are never announced into the world and some of us wait fifty years.

I am finally announced into being in this moment in a random hotel in Manhattan unraveling my past, present, and possible future. There are so many political ramifications of this new body—ramifications I both know and can’t know until I begin to live them.

The next morning, I will go down to the hotel restaurant for breakfast. “Good morning, sir, what can I get you? Coffee, sir?” I will read the news on my phone: a white supremacist is being asked to resign from the White House; it’s the lead story. Second up, another judge has granted a temporary restraining order on the president’s newly revised travel ban, from seven countries to six. This judge also thinks it is discriminatory, even with Iran dropped from the list. My waiter is from India I learn after he brings me my oatmeal; he tells me he and his wife recently immigrated here. Just in time, I think to myself. They both work at the restaurant. He forgets to bring me my orange juice. I will get free breakfast for the rest of the week, with many apologies to this newly minted white man. When I ask for more coffee, he calls me “boss,” a term I will hear often from now on from men of color in service positions: valets, waiters, taxi drivers. I am stunned and embarrassed by the term, the sudden privilege and power that emanates from my white male skin. I don’t feel it in my body yet. But the world can see it.

I come into being as a white man in 2017. White male supremacists occupy the White House. Immigrants are deported and denied entry to the United States. Black lives don’t matter to the politicians controlling Congress. I am announced to the world as a man eight months before #MeToo will fill our social media and news feeds—women will unsilence themselves and begin the arduous process of dismantling the lives of individual men, one by one by one, for unspeakable acts of discrimination, harassment, assault, and abuse. No part of this two-year stretch has been more divisive than the Republican Party’s insistence on appointing Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. No moment has been more despairing than listening to Susan Collins, a woman, a senator, say that Christine Blasey Ford was likely assaulted but that it wasn’t by Kavanaugh—to hear one woman say to another woman that she doesn’t believe her, among a chorus of white men who decry what has been done to Kavanaugh, that he is the victim, not Blasey Ford. Depending on who sees me and in what context, my body is grouped with these men and Collins in this moment in history—a threat not just to women but also to a fragile democracy on the brink of collapse, in part over a gender divide that has never been more volatile.

This book is a layperson’s anthropological exploration of living a double life, Double consciousness, to borrow a term from W.E.B. Dubois, is a permanent condition of a trans person who has lived a life in one body and then another. The nuances of doubling require an untangling of two bodies, two distinct perspectives, two lives lived. I seek to do justice to the complexity of this emotional travel as I write this book in a number of different cities and through an evolving bodily transubstantiation where in one moment I am material subject matter to be consumed and in another I feel like a holy essence, my body and blood both sacrificed and blessed into being.

For most of my life, this process of becoming feels lethal, the disparate parts always at war with one another. I am born to the name Polly, but I never feel like her. I spend decades trying to know her, shape her into something that I can bear to live with. I medicate her, I dress her like I imagine Carl would look if he were allowed to live. On two occasions, I try to kill her off. The moment at the Hotel Chandler when I am lifting my hands over my head and jumping up and down and taking photos and posting them everywhere is the beginning of revelations, the ones I will try to convey to you in these pages. I become solid enough to share with you how my becoming is filled with contradictions and questions, and sometimes I have the courage to look back and tell you about what Polly went through and other times I want to convince you I was always only Carl.

I purposely choose a name to reflect my past and present. I don’t know all the ways this name will matter to the life that will unfold when I choose it. I do know that I am fifty-one when I change my name. I can’t imagine suddenly being summoned as Paul, or my favorite Italian name, Giacomo, Jack in English. I know that if I heard these names at this stage in my life, I wouldn’t recognize them as me. Polly Kathleen Carl. What parts of her can I keep? My father and brothers have often mistakenly been called Carl, as if their last name might be their first. P. Carl is continuity. I hold on to a piece of her and acknowledge that he has always been with me. I had no idea the trouble this name would cause the world. It crashes the computer systems at the pharmacy and the airport. It makes my passport look like it’s missing a first name and at every border crossing I must convince the customs agent that this is me. Each exchange requires a shift in vantage point for what can constitute a name. “Yes, this is really my legal name,” I say over and over. “I go by Carl.” Though the first time we meet, people insist on calling me “P,” as if what is first in the order of a name must always come first.

This is also a book about changing a name, a life, and a gender—crossing a seemingly indistinguishable line and all the implications of that crossing—for me, my family, my friends—in an American political landscape that misunderstands transgender bodies even as some progress is being made toward accepting that we exist, we are human, and we deserve a livable life. I lived half a century first as a girl and then as a queer woman, and now for almost two years as a man. What does it mean for a body to transform? Do those changes transform an inner life, a person, and his personality? Am I fifty-two years old? Or have I just been born? What do you see? What do I feel? What do I know about America’s fraught relationship with gender having inhabited these two bodies? Is there a revolution lurking in my double consciousness, in transgender bodies, that might reinvent discussions of gender? Can I, can other white trans men, bring something new to the conversation about white masculinity? In the words of Christine Blasey Ford, an American hero, my purpose in coming forward is to be “helpful.”

If you had asked me five years ago, before I started taking testosterone, “Are you a man?” I would have said no. I would have said, as I wrote in an essay at the time, “A Boy in a Man’s Theatre,” that I was a boy—that I had missed the rites of passage to adulthood because I was never a girl and never a woman, and I didn’t want the baggage that comes with being a man. I desired to live in perpetual boyhood because boys are infinitely more likable than men.

Everyone around me was comfortable with this. They liked the image of me as a boy. I looked the part—youthful, short-haired, and short in stature, dressed in little tailored suits. My wife joked, “You dress like a businessman, a tiny toy businessman.” The last lines of my wedding vows to Lynette from 2012 were, “And I own these words now and say them with all the conviction a boy can muster: I love you, Mary Lynette D’Amico, and vow to do so forever and always.” As long as I stayed in the container of my female body, I could call myself a boy and still be a heroic woman, happily married to Lynette, challenging men and their dominance in my profession and inside my family.

It’s an important distinction, and one I didn’t understand until I crossed over from boy to man. In the queer community, boy is an affectionate term; the slang boi is used as another way to refer to younger or perhaps “less butch” butches. Butches and bois aren’t men, they are queer women. Lesbians, my wife for example, have expressly defined their desire in opposition to men but not to butches and to boys (that is, tomboys). When women marry butches and boys, they are still marrying women on the legal certificates.

Boys also have less accountability than men. I keep thinking of the family of the president. His two older sons are men and get called out for hunting endangered species, for lying, for being sexist. But the youngest son is only twelve. I don’t know what he does, but there is a consensus that he’s off-limits to a certain degree because he’s a boy. There is an accountability that comes with white adult masculinity, and if you’ve spent your life minimizing your contact with it and its power over you, suddenly being confronted by a white man in a marriage or friendship can be an unforgivable transgression.

Being a boy kept me in a body that presented as androgynous, quirky, tomboy, singular. It was a queer body that created discomfort for the world, but my family, friends, and most of the people in my profession embraced it as the true me; they had accepted and counted on my queerness. The opposite happened when I became a man. The world scooped me up and gave me a warm welcome in places I could never before have entered comfortably, and many of the people closest to me turned away, betrayed by a transition they took personally.

My father soured me to the idea of manhood from the get-go. My wife of twenty years wasn’t encouraging about the subject. She has identified as a lesbian for forty years, and though she loves boys, especially our nephews, men haven’t been of particular interest to her. She never had any intention of living with one. And as much as I had done every single thing to look like a man and live like one, I denied wanting to become one because I didn’t want to become my father or lose my lesbian lover or be a failed feminist and intellectual.

As a feminist for my entire adult life, and as someone who completed a PhD in cultural studies, my transition creates ripples of complications for my brain, a brain that lived with certainty about the elasticity of gender and its capacity to flex and expand with the culture. I desperately wanted to inhabit my ambiguity as a political position, as a way to say that I would not perpetuate a binary that almost killed me, but when I heard the definitive nature of that “sir” inside the Hotel Chandler, my body never wanted to look back. I imagined myself packing a single bag, a change of clothes, my passport, and some cash, and boarding a plane to another country to live the life I had missed for whatever time I had left on this earth.

My head and my body were at odds. I had been scrutinizing masculinity my whole life, trying to perfectly replicate it in my gestures and clothes and physique. I stayed very trim, wore only men’s clothes, studied the latest short-hair styles, tried to keep the tenor of my voice low, and always played the roles that I thought men played. I earned. I mowed the lawn. I kept track of the finances. I filed the taxes. I shoveled the snow. I lugged the air conditioners from the basement to the bedroom windows every summer. I always drove. I was grossly deficient at housecleaning. I owned only one bathroom towel when my wife, Lynette, first moved into my bachelor pad. But I insisted that I was not a man, until at age fifty, the knowledge that I had only ever felt like a man and a boy poured out of me with a certainty that I would never deny again. I learned quickly that it’s okay to theorize about bodies, but altering a body’s sex is perhaps the greatest disruption to the social order that makes up friendship, work, and love.

My body’s biological need is to live as a man. It presents a gender theory problem. My PhD had trained me to put all of my emphasis on the cultural manifestations of gender as a construct. I see queer and trans people wearing T-shirts now that read “Gender Is a Social Construct.” I think the oversimplification of that is as dangerous as is the reinforcing of genitalia defining sex as God’s will. A construct is something we make; it is a materiality that is drawn from the offerings of culture and reinscribed so seamlessly that it feels natural. For me, living as a woman was a construct. I am not a philosopher and this book is not a treatise on the ontological nature of being. What I know is that this transition wasn’t something I knew I wanted, it wasn’t something I chose. It was a longing and a desire so deeply embedded in my body that I could barely access it because every part of my life, all that culture had to offer, told me I couldn’t have it. I believe my maleness is the truest and most stable thing about me, and has been so since my earliest memories. I experience myself as a man; not as a construct, but how I construct that man knowing what I know as a woman is my work now.

There is a photo of me at age four with my older brother and some of my cousins. I’m wearing my brother Tim’s purple paisley shirt, an article of clothing I adored; it’s unbuttoned and my naked chest is sticking out proudly and I have a huge smile on my face. That boy knew who he was. How the culture of my childhood and most of my adulthood made living and exploring that truth both impossible and deadly is the trauma that formed my emotional core, separated my soul from my living, breathing existence. My body could feel alive and my heart could feel warm only when testosterone reunited me with that boy at age four who, I so clearly remember, dreamed of being a man.

“That’s what she wanted. White picket fences. Happy hubby, romantic, man and woman. And yet, she had the body she had, and she was who she was.”

These are the words of the best friend of the first transgender person killed in the United States in 2018. Christa Leigh Steele-Knudslien was bludgeoned with a hammer by her husband and then stabbed in the back and through the heart. “She had the body she had.” These six words play over and over again in my head. The inescapable doubling of the transgender body, expressed as if doubling means a life can never be complete, as if a certain combination of body parts is necessary to achieve “happiness,” even for a best friend who knows which pronouns to use.

How to tell you what it feels like? How to bring you inside this experience with me, so that you can be not just openhearted, but so you can know me, so that when I die, you can say the right words? Please don’t say “he had the body he had.” Please don’t ask me if I feel incomplete because the top half doesn’t match the bottom, as one good friend did. I love this body and all its contradictions. Please know that many things are true about my history that can never add up. I was conscripted to the girls’ locker room and the women’s restroom, but when I was speaking to you I was always speaking to you as the boy I was and the man I am. I knew I had to check the F box on my passport application to go to college in London, but when I saw the photos of me standing next to Windsor Castle, I didn’t recognize her and turned away. I will always feel the rage of being a woman who was told on too many occasions that I was aggressive and ambitious and angry. I feel those feelings as her, even though she’s me and not me. An inner self can learn to walk parallel with a constructed self and know and not know it simultaneously.

I am transgender to my past, to all the people who knew me as Polly. Friends will say, when I am not around, “You know, he was she before he was he.” I will enter rooms where my past is present and watch people search for the woman in me. I am an object of curiosity in one setting and the embodiment of privilege as I flaunt my whiteness and masculinity in another. I am a spy. I watch men and how they behave: I am at the pool. A man dismisses a young woman’s kind request. She has reserved the lane he is in for the lesson she will teach, the schedule posted on the door to the entry to the pool. “This is my lane.” He sneers at her and swims on. The next time he pops his head out of the water I shout at him, “Move the fuck over, buddy,” and he does. My body is at risk as trans and it has incredible mobility as white and male. I represent a threat to the lone woman walking in the park with her dog, and I am perhaps the greatest hope for the young trans students at the college where I teach, the only transgender professor as of this writing.

I have never felt so much. I am like a newborn who is expected to drive sixty-five miles per hour down the highway, but I can’t see above the steering wheel. I crane my neck upward to get a glimpse of wholeness in the rearview mirror and weep with relief at that gorgeous gray-haired man. I want to believe that my past is behind me, that I will look at him forever, that we are undivided. There is an episode in the Amazon television series Transparent in which the trans women on the show have their childhood photos altered to reinvent their history, to imagine their pasts different from what they were, to see themselves as the young girls they wish they had been. I want this, too, at the beginning. But I am a married man, and this transition isn’t singular. I was a lesbian lover once and now I am a husband. What to do with my history of loving the same woman for twenty years when both bodies worship the ground she walks on?

Old relationships formed under a dead name flounder, dead-ending, ending. “You changed,” they say—all the ways of coming into being as a transgender person threaten the chronology of history and memories for others. “Be prepared to lose everything,” my healthcare provider tells me when I start testosterone. This hardly feels like a warning because I think I can’t lose everything fast enough. I want her to stop talking and just give me that testosterone shot. But she was right, and over the course of these two years I have to face the loss. It’s taboo in the trans community to use someone’s “dead name.” Do not, for example, put a dead name in an obituary, or refer to the time when she was her if he is now him. I break that taboo in this book. You must know Polly, as much as I will begrudge telling you, because Polly knows so much about Carl and vice versa.

Polly knows what it is to be treated as a woman and to live inside the confines of the female gender. Carl knows the freedom of being a man and what happens in spaces where only men are allowed to go. Polly felt intensely the discrimination of being a successful woman, a leader in American theater. Carl witnesses the discrimination against women everywhere now in a way that Polly’s body couldn’t take in. I am a work in progress, always doubling as different selves in different spaces, still learning how to navigate the multiple truths this body inhabits. When I shout at that man in the pool, it’s Polly’s memories and Carl’s body.

I am slowly being surrounded by many young people who define themselves as nonbinary, friends who refuse to pick a side and use the pronoun “they.” And this possibility, one that feels very recent, may change the gender landscape for the better. It is a different experience of being trans and one that I am eager to continue to learn from. At the same time, white masculinity is more defined and powerful than ever—in the workplace, in the government, in the gym where I work out every day, in my little apartment in Berlin where I watch Kavanaugh testify, shout in anger, cry out over the indignation of being held accountable, lie repeatedly, and then get sworn into a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.

I walk in the world as a man. I am experiencing that privilege for the very first time and I love it unapologetically. This side of the binary suits me. But I can’t walk freely and act like I don’t know what women face in a culture of men who dismiss a women’s terror and traumas and history as unworthy of consideration. I will not recover from what I am seeing, a woman recounting her deepest pain in front of a group of disinterested and disbelieving men who run our country. The part of the assault most etched in Blasey Ford’s memory, of two boys/men laughing, not at her, but with each other over their power to destroy her life. I know she did not forget who was in that room. As my visible queerness has dissipated, and the fog of being disassociated from my body has lifted, I see with crystalline clearness the power that operates in men’s bodies—power that threatens the very integrity of our nation-state.

I see all the flaws of men, all the ways their fragility makes them dangerous and powerful and dismissive and sure that they know it all, and I love being a man. I love masculinity and I love hanging out with men. My body is a contradiction. I feel a fiery rage toward men for treating me like a woman, for making women seem crazy and emotional and inferior, for what men did to me. I feel so much joy living in a man’s body, my natural physicality, and I am trying to find a path toward becoming a good man.

If we are to survive America’s current war over who gets to have a livable life, we must confront and understand masculinity and we must all seek some version of double consciousness, to be inside and outside of identities that are not our own. Transgender people have something important to offer this conversation, and perhaps if we are allowed to speak, if we’re heard, we too will have a chance at more livable lives.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

When bodies gather as they do to express their indignation and to enact their plural existence in public space, they are also making broader demands; they are demanding to be recognized, to be valued, they are exercising a right to appear, to exercise freedom, and they are demanding a livable life.

—Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly

I have been living as a white, Midwestern woman for fifty years and ten months, until one weekend in March, I cross a line. It comes unexpectedly on this particular day, but I’ve been thinking and expecting it for as long as I can remember. The Hotel Chandler in Midtown Manhattan: seven months on testosterone, I check in at about 6 P.M. “Good evening, sir, how are you?” This isn’t my first “sir”—they have come and gone my entire life, and more often in recent weeks. But it’s the start of something that from this “sir” forward will be my new life. On March 16, 2017, I become a man.

What changed from yesterday and the day before yesterday? What is this fine line of gender that makes me a woman one day and a man the next? Did my jawline get just square enough, my voice deep enough? Did my hairline recede enough? All I know is that from March 16 forward, I am finally me. I take a selfie and send it to my wife, with a text message: “I’m me now.” I can’t fucking believe it. I am finally me. I am visible for the first time, just two months shy of my fifty-first birthday. This rite of passage, this moment of being welcomed into the world as embodied is something most people experience at the moment of birth, or even earlier, at the moment of those ultrasound pictures of unborn babies that all my friends with children have, already sexed by their obstetrician and their parents. Some of us are never announced into the world and some of us wait fifty years.

I am finally announced into being in this moment in a random hotel in Manhattan unraveling my past, present, and possible future. There are so many political ramifications of this new body—ramifications I both know and can’t know until I begin to live them.

The next morning, I will go down to the hotel restaurant for breakfast. “Good morning, sir, what can I get you? Coffee, sir?” I will read the news on my phone: a white supremacist is being asked to resign from the White House; it’s the lead story. Second up, another judge has granted a temporary restraining order on the president’s newly revised travel ban, from seven countries to six. This judge also thinks it is discriminatory, even with Iran dropped from the list. My waiter is from India I learn after he brings me my oatmeal; he tells me he and his wife recently immigrated here. Just in time, I think to myself. They both work at the restaurant. He forgets to bring me my orange juice. I will get free breakfast for the rest of the week, with many apologies to this newly minted white man. When I ask for more coffee, he calls me “boss,” a term I will hear often from now on from men of color in service positions: valets, waiters, taxi drivers. I am stunned and embarrassed by the term, the sudden privilege and power that emanates from my white male skin. I don’t feel it in my body yet. But the world can see it.

I come into being as a white man in 2017. White male supremacists occupy the White House. Immigrants are deported and denied entry to the United States. Black lives don’t matter to the politicians controlling Congress. I am announced to the world as a man eight months before #MeToo will fill our social media and news feeds—women will unsilence themselves and begin the arduous process of dismantling the lives of individual men, one by one by one, for unspeakable acts of discrimination, harassment, assault, and abuse. No part of this two-year stretch has been more divisive than the Republican Party’s insistence on appointing Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. No moment has been more despairing than listening to Susan Collins, a woman, a senator, say that Christine Blasey Ford was likely assaulted but that it wasn’t by Kavanaugh—to hear one woman say to another woman that she doesn’t believe her, among a chorus of white men who decry what has been done to Kavanaugh, that he is the victim, not Blasey Ford. Depending on who sees me and in what context, my body is grouped with these men and Collins in this moment in history—a threat not just to women but also to a fragile democracy on the brink of collapse, in part over a gender divide that has never been more volatile.

This book is a layperson’s anthropological exploration of living a double life, Double consciousness, to borrow a term from W.E.B. Dubois, is a permanent condition of a trans person who has lived a life in one body and then another. The nuances of doubling require an untangling of two bodies, two distinct perspectives, two lives lived. I seek to do justice to the complexity of this emotional travel as I write this book in a number of different cities and through an evolving bodily transubstantiation where in one moment I am material subject matter to be consumed and in another I feel like a holy essence, my body and blood both sacrificed and blessed into being.

For most of my life, this process of becoming feels lethal, the disparate parts always at war with one another. I am born to the name Polly, but I never feel like her. I spend decades trying to know her, shape her into something that I can bear to live with. I medicate her, I dress her like I imagine Carl would look if he were allowed to live. On two occasions, I try to kill her off. The moment at the Hotel Chandler when I am lifting my hands over my head and jumping up and down and taking photos and posting them everywhere is the beginning of revelations, the ones I will try to convey to you in these pages. I become solid enough to share with you how my becoming is filled with contradictions and questions, and sometimes I have the courage to look back and tell you about what Polly went through and other times I want to convince you I was always only Carl.

I purposely choose a name to reflect my past and present. I don’t know all the ways this name will matter to the life that will unfold when I choose it. I do know that I am fifty-one when I change my name. I can’t imagine suddenly being summoned as Paul, or my favorite Italian name, Giacomo, Jack in English. I know that if I heard these names at this stage in my life, I wouldn’t recognize them as me. Polly Kathleen Carl. What parts of her can I keep? My father and brothers have often mistakenly been called Carl, as if their last name might be their first. P. Carl is continuity. I hold on to a piece of her and acknowledge that he has always been with me. I had no idea the trouble this name would cause the world. It crashes the computer systems at the pharmacy and the airport. It makes my passport look like it’s missing a first name and at every border crossing I must convince the customs agent that this is me. Each exchange requires a shift in vantage point for what can constitute a name. “Yes, this is really my legal name,” I say over and over. “I go by Carl.” Though the first time we meet, people insist on calling me “P,” as if what is first in the order of a name must always come first.

This is also a book about changing a name, a life, and a gender—crossing a seemingly indistinguishable line and all the implications of that crossing—for me, my family, my friends—in an American political landscape that misunderstands transgender bodies even as some progress is being made toward accepting that we exist, we are human, and we deserve a livable life. I lived half a century first as a girl and then as a queer woman, and now for almost two years as a man. What does it mean for a body to transform? Do those changes transform an inner life, a person, and his personality? Am I fifty-two years old? Or have I just been born? What do you see? What do I feel? What do I know about America’s fraught relationship with gender having inhabited these two bodies? Is there a revolution lurking in my double consciousness, in transgender bodies, that might reinvent discussions of gender? Can I, can other white trans men, bring something new to the conversation about white masculinity? In the words of Christine Blasey Ford, an American hero, my purpose in coming forward is to be “helpful.”

If you had asked me five years ago, before I started taking testosterone, “Are you a man?” I would have said no. I would have said, as I wrote in an essay at the time, “A Boy in a Man’s Theatre,” that I was a boy—that I had missed the rites of passage to adulthood because I was never a girl and never a woman, and I didn’t want the baggage that comes with being a man. I desired to live in perpetual boyhood because boys are infinitely more likable than men.

Everyone around me was comfortable with this. They liked the image of me as a boy. I looked the part—youthful, short-haired, and short in stature, dressed in little tailored suits. My wife joked, “You dress like a businessman, a tiny toy businessman.” The last lines of my wedding vows to Lynette from 2012 were, “And I own these words now and say them with all the conviction a boy can muster: I love you, Mary Lynette D’Amico, and vow to do so forever and always.” As long as I stayed in the container of my female body, I could call myself a boy and still be a heroic woman, happily married to Lynette, challenging men and their dominance in my profession and inside my family.

It’s an important distinction, and one I didn’t understand until I crossed over from boy to man. In the queer community, boy is an affectionate term; the slang boi is used as another way to refer to younger or perhaps “less butch” butches. Butches and bois aren’t men, they are queer women. Lesbians, my wife for example, have expressly defined their desire in opposition to men but not to butches and to boys (that is, tomboys). When women marry butches and boys, they are still marrying women on the legal certificates.

Boys also have less accountability than men. I keep thinking of the family of the president. His two older sons are men and get called out for hunting endangered species, for lying, for being sexist. But the youngest son is only twelve. I don’t know what he does, but there is a consensus that he’s off-limits to a certain degree because he’s a boy. There is an accountability that comes with white adult masculinity, and if you’ve spent your life minimizing your contact with it and its power over you, suddenly being confronted by a white man in a marriage or friendship can be an unforgivable transgression.

Being a boy kept me in a body that presented as androgynous, quirky, tomboy, singular. It was a queer body that created discomfort for the world, but my family, friends, and most of the people in my profession embraced it as the true me; they had accepted and counted on my queerness. The opposite happened when I became a man. The world scooped me up and gave me a warm welcome in places I could never before have entered comfortably, and many of the people closest to me turned away, betrayed by a transition they took personally.

My father soured me to the idea of manhood from the get-go. My wife of twenty years wasn’t encouraging about the subject. She has identified as a lesbian for forty years, and though she loves boys, especially our nephews, men haven’t been of particular interest to her. She never had any intention of living with one. And as much as I had done every single thing to look like a man and live like one, I denied wanting to become one because I didn’t want to become my father or lose my lesbian lover or be a failed feminist and intellectual.

As a feminist for my entire adult life, and as someone who completed a PhD in cultural studies, my transition creates ripples of complications for my brain, a brain that lived with certainty about the elasticity of gender and its capacity to flex and expand with the culture. I desperately wanted to inhabit my ambiguity as a political position, as a way to say that I would not perpetuate a binary that almost killed me, but when I heard the definitive nature of that “sir” inside the Hotel Chandler, my body never wanted to look back. I imagined myself packing a single bag, a change of clothes, my passport, and some cash, and boarding a plane to another country to live the life I had missed for whatever time I had left on this earth.

My head and my body were at odds. I had been scrutinizing masculinity my whole life, trying to perfectly replicate it in my gestures and clothes and physique. I stayed very trim, wore only men’s clothes, studied the latest short-hair styles, tried to keep the tenor of my voice low, and always played the roles that I thought men played. I earned. I mowed the lawn. I kept track of the finances. I filed the taxes. I shoveled the snow. I lugged the air conditioners from the basement to the bedroom windows every summer. I always drove. I was grossly deficient at housecleaning. I owned only one bathroom towel when my wife, Lynette, first moved into my bachelor pad. But I insisted that I was not a man, until at age fifty, the knowledge that I had only ever felt like a man and a boy poured out of me with a certainty that I would never deny again. I learned quickly that it’s okay to theorize about bodies, but altering a body’s sex is perhaps the greatest disruption to the social order that makes up friendship, work, and love.

My body’s biological need is to live as a man. It presents a gender theory problem. My PhD had trained me to put all of my emphasis on the cultural manifestations of gender as a construct. I see queer and trans people wearing T-shirts now that read “Gender Is a Social Construct.” I think the oversimplification of that is as dangerous as is the reinforcing of genitalia defining sex as God’s will. A construct is something we make; it is a materiality that is drawn from the offerings of culture and reinscribed so seamlessly that it feels natural. For me, living as a woman was a construct. I am not a philosopher and this book is not a treatise on the ontological nature of being. What I know is that this transition wasn’t something I knew I wanted, it wasn’t something I chose. It was a longing and a desire so deeply embedded in my body that I could barely access it because every part of my life, all that culture had to offer, told me I couldn’t have it. I believe my maleness is the truest and most stable thing about me, and has been so since my earliest memories. I experience myself as a man; not as a construct, but how I construct that man knowing what I know as a woman is my work now.

There is a photo of me at age four with my older brother and some of my cousins. I’m wearing my brother Tim’s purple paisley shirt, an article of clothing I adored; it’s unbuttoned and my naked chest is sticking out proudly and I have a huge smile on my face. That boy knew who he was. How the culture of my childhood and most of my adulthood made living and exploring that truth both impossible and deadly is the trauma that formed my emotional core, separated my soul from my living, breathing existence. My body could feel alive and my heart could feel warm only when testosterone reunited me with that boy at age four who, I so clearly remember, dreamed of being a man.

“That’s what she wanted. White picket fences. Happy hubby, romantic, man and woman. And yet, she had the body she had, and she was who she was.”

These are the words of the best friend of the first transgender person killed in the United States in 2018. Christa Leigh Steele-Knudslien was bludgeoned with a hammer by her husband and then stabbed in the back and through the heart. “She had the body she had.” These six words play over and over again in my head. The inescapable doubling of the transgender body, expressed as if doubling means a life can never be complete, as if a certain combination of body parts is necessary to achieve “happiness,” even for a best friend who knows which pronouns to use.

How to tell you what it feels like? How to bring you inside this experience with me, so that you can be not just openhearted, but so you can know me, so that when I die, you can say the right words? Please don’t say “he had the body he had.” Please don’t ask me if I feel incomplete because the top half doesn’t match the bottom, as one good friend did. I love this body and all its contradictions. Please know that many things are true about my history that can never add up. I was conscripted to the girls’ locker room and the women’s restroom, but when I was speaking to you I was always speaking to you as the boy I was and the man I am. I knew I had to check the F box on my passport application to go to college in London, but when I saw the photos of me standing next to Windsor Castle, I didn’t recognize her and turned away. I will always feel the rage of being a woman who was told on too many occasions that I was aggressive and ambitious and angry. I feel those feelings as her, even though she’s me and not me. An inner self can learn to walk parallel with a constructed self and know and not know it simultaneously.

I am transgender to my past, to all the people who knew me as Polly. Friends will say, when I am not around, “You know, he was she before he was he.” I will enter rooms where my past is present and watch people search for the woman in me. I am an object of curiosity in one setting and the embodiment of privilege as I flaunt my whiteness and masculinity in another. I am a spy. I watch men and how they behave: I am at the pool. A man dismisses a young woman’s kind request. She has reserved the lane he is in for the lesson she will teach, the schedule posted on the door to the entry to the pool. “This is my lane.” He sneers at her and swims on. The next time he pops his head out of the water I shout at him, “Move the fuck over, buddy,” and he does. My body is at risk as trans and it has incredible mobility as white and male. I represent a threat to the lone woman walking in the park with her dog, and I am perhaps the greatest hope for the young trans students at the college where I teach, the only transgender professor as of this writing.

I have never felt so much. I am like a newborn who is expected to drive sixty-five miles per hour down the highway, but I can’t see above the steering wheel. I crane my neck upward to get a glimpse of wholeness in the rearview mirror and weep with relief at that gorgeous gray-haired man. I want to believe that my past is behind me, that I will look at him forever, that we are undivided. There is an episode in the Amazon television series Transparent in which the trans women on the show have their childhood photos altered to reinvent their history, to imagine their pasts different from what they were, to see themselves as the young girls they wish they had been. I want this, too, at the beginning. But I am a married man, and this transition isn’t singular. I was a lesbian lover once and now I am a husband. What to do with my history of loving the same woman for twenty years when both bodies worship the ground she walks on?

Old relationships formed under a dead name flounder, dead-ending, ending. “You changed,” they say—all the ways of coming into being as a transgender person threaten the chronology of history and memories for others. “Be prepared to lose everything,” my healthcare provider tells me when I start testosterone. This hardly feels like a warning because I think I can’t lose everything fast enough. I want her to stop talking and just give me that testosterone shot. But she was right, and over the course of these two years I have to face the loss. It’s taboo in the trans community to use someone’s “dead name.” Do not, for example, put a dead name in an obituary, or refer to the time when she was her if he is now him. I break that taboo in this book. You must know Polly, as much as I will begrudge telling you, because Polly knows so much about Carl and vice versa.

Polly knows what it is to be treated as a woman and to live inside the confines of the female gender. Carl knows the freedom of being a man and what happens in spaces where only men are allowed to go. Polly felt intensely the discrimination of being a successful woman, a leader in American theater. Carl witnesses the discrimination against women everywhere now in a way that Polly’s body couldn’t take in. I am a work in progress, always doubling as different selves in different spaces, still learning how to navigate the multiple truths this body inhabits. When I shout at that man in the pool, it’s Polly’s memories and Carl’s body.

I am slowly being surrounded by many young people who define themselves as nonbinary, friends who refuse to pick a side and use the pronoun “they.” And this possibility, one that feels very recent, may change the gender landscape for the better. It is a different experience of being trans and one that I am eager to continue to learn from. At the same time, white masculinity is more defined and powerful than ever—in the workplace, in the government, in the gym where I work out every day, in my little apartment in Berlin where I watch Kavanaugh testify, shout in anger, cry out over the indignation of being held accountable, lie repeatedly, and then get sworn into a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.

I walk in the world as a man. I am experiencing that privilege for the very first time and I love it unapologetically. This side of the binary suits me. But I can’t walk freely and act like I don’t know what women face in a culture of men who dismiss a women’s terror and traumas and history as unworthy of consideration. I will not recover from what I am seeing, a woman recounting her deepest pain in front of a group of disinterested and disbelieving men who run our country. The part of the assault most etched in Blasey Ford’s memory, of two boys/men laughing, not at her, but with each other over their power to destroy her life. I know she did not forget who was in that room. As my visible queerness has dissipated, and the fog of being disassociated from my body has lifted, I see with crystalline clearness the power that operates in men’s bodies—power that threatens the very integrity of our nation-state.

I see all the flaws of men, all the ways their fragility makes them dangerous and powerful and dismissive and sure that they know it all, and I love being a man. I love masculinity and I love hanging out with men. My body is a contradiction. I feel a fiery rage toward men for treating me like a woman, for making women seem crazy and emotional and inferior, for what men did to me. I feel so much joy living in a man’s body, my natural physicality, and I am trying to find a path toward becoming a good man.

If we are to survive America’s current war over who gets to have a livable life, we must confront and understand masculinity and we must all seek some version of double consciousness, to be inside and outside of identities that are not our own. Transgender people have something important to offer this conversation, and perhaps if we are allowed to speak, if we’re heard, we too will have a chance at more livable lives.

Descriere

A debut memoir that explores one man’s gender transition amid a pivotal political moment in America.