Bernard Maybeck: Visionary Architect

Autor Sally Byrne Woodbridge Fotografii de Richard Barnesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 oct 2006

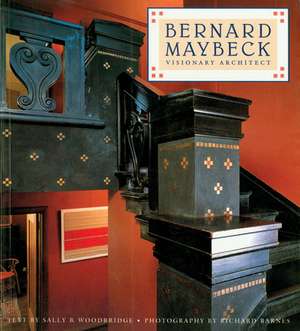

Now available in paperback, this bestselling volume chronicles one of the most innovative, influential, and beloved architects of the early 20th century.

Gracefully written and brilliantly illustrated, this handsome new volume captures the vision, the wit, and the down-to-earth inventiveness of one of the most influential and beloved architects of the early twentieth century.

Raised in Greenwich Village and trained in Paris, Maybeck spent most of his long career in northern California. An irrepressible bohemian with no desire to run a large office, he spent much of his time designing houses for friends and family, as well as for other patrons so loyal that they often hired him to design more than one house. Maybeck also created two of the most beautiful buildings in all of California: the exhilarating Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley, and the gloriously romantic Palace of Fine Arts, in San Francisco.

This incisive overview—the first to feature color reproductions of Maybeck's exquisite interiors and exteriors—analyzes every aspect of his life and work. Not only his architecture but also his furniture, his lighting designs, and his innovations in fire-resistant construction are thoroughly discussed and illustrated. The book is also enlivened by documentary photographs, by clearly drawn plans, and by several of Maybeck's dazzling, previously unpublished visionary drawings.

Bernard Maybeck is a major study of an internationally significant architect whose environmentally responsive work has much to offer today's designers and whose houses have given enormous pleasure to those fortunate enough to visit or dwell in them.

Gracefully written and brilliantly illustrated, this handsome new volume captures the vision, the wit, and the down-to-earth inventiveness of one of the most influential and beloved architects of the early twentieth century.

Raised in Greenwich Village and trained in Paris, Maybeck spent most of his long career in northern California. An irrepressible bohemian with no desire to run a large office, he spent much of his time designing houses for friends and family, as well as for other patrons so loyal that they often hired him to design more than one house. Maybeck also created two of the most beautiful buildings in all of California: the exhilarating Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley, and the gloriously romantic Palace of Fine Arts, in San Francisco.

This incisive overview—the first to feature color reproductions of Maybeck's exquisite interiors and exteriors—analyzes every aspect of his life and work. Not only his architecture but also his furniture, his lighting designs, and his innovations in fire-resistant construction are thoroughly discussed and illustrated. The book is also enlivened by documentary photographs, by clearly drawn plans, and by several of Maybeck's dazzling, previously unpublished visionary drawings.

Bernard Maybeck is a major study of an internationally significant architect whose environmentally responsive work has much to offer today's designers and whose houses have given enormous pleasure to those fortunate enough to visit or dwell in them.

Preț: 197.34 lei

Preț vechi: 241.21 lei

-18% Nou

Puncte Express: 296

Preț estimativ în valută:

37.76€ • 39.53$ • 31.24£

37.76€ • 39.53$ • 31.24£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789201324

ISBN-10: 0789201321

Pagini: 248

Dimensiuni: 251 x 279 x 23 mm

Greutate: 1.44 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 0789201321

Pagini: 248

Dimensiuni: 251 x 279 x 23 mm

Greutate: 1.44 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Cuprins

Table of Contents from Bernard Maybeck

Introduction

Foundations

Simple Homes and Clubhouses

The Hearst Commissions

The Church and the Palace

Mid-Career Houses

Projects for Earle C. Anthony

After the Fire

Notes

Acknowledgments

Buildings and Projects by Bernard Maybeck

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Foundations

Simple Homes and Clubhouses

The Hearst Commissions

The Church and the Palace

Mid-Career Houses

Projects for Earle C. Anthony

After the Fire

Notes

Acknowledgments

Buildings and Projects by Bernard Maybeck

Selected Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

Praise for Bernard Maybeck: Visionary Architect:

"One of the unclassifiable originals in American architecture—along with Frank Furness, Bruce Goff, and, today, Frank Gehry—Bernard Maybeck (1862-1957) devised a completely personal vocabulary of building, assembling a harmonious whole from an unlikely array of unusual forms and inventive details…Richard Barnes's ravishing photographs are the first to convey in color the complex splendors of Maybeck's inimitable achievement, and they succeed with appropriate vigor and warmth. Likewise, Sally B. Woodbridge's sympathetic text shows considerable understanding of this Whitmanesque figure." — Martin Filler, New York Times Book Review

"This excellent biography thoroughly documents the often fantastic and always interesting work of California architect Bernard Maybeck…Highly recommended for collections of architecture, design, and art." — Library Journal

"One of the unclassifiable originals in American architecture—along with Frank Furness, Bruce Goff, and, today, Frank Gehry—Bernard Maybeck (1862-1957) devised a completely personal vocabulary of building, assembling a harmonious whole from an unlikely array of unusual forms and inventive details…Richard Barnes's ravishing photographs are the first to convey in color the complex splendors of Maybeck's inimitable achievement, and they succeed with appropriate vigor and warmth. Likewise, Sally B. Woodbridge's sympathetic text shows considerable understanding of this Whitmanesque figure." — Martin Filler, New York Times Book Review

"This excellent biography thoroughly documents the often fantastic and always interesting work of California architect Bernard Maybeck…Highly recommended for collections of architecture, design, and art." — Library Journal

Notă biografică

Sally B. Woodbridge, who lives in Berkeley, California, is an architectural critic and historian whose previous books include Bay Area Houses.

Richard Barnes is a San Francisco based photographer who divides his time between commissioned work and personal projects. Noted for his photographs of work by Julia Morgan and other architects, he is currently photographing the Egyptian City of the Dead.

Richard Barnes is a San Francisco based photographer who divides his time between commissioned work and personal projects. Noted for his photographs of work by Julia Morgan and other architects, he is currently photographing the Egyptian City of the Dead.

Extras

Excerpt from Bernard Maybeck

Introduction

Nearly everyone who has written about Bernard Maybeck has described him as naive, even calling him the Great Naïf, as though he had reached a pinnacle of otherworldliness. Yet this benign genie, regarded by even his fellow architects as a crank and a dreamer, instigated and achieved projects with a lasting value that eluded more grounded and practical men. Other talented architects, who were nobody's fools and who did not spare themselves in pursuit of influence and fame, gained relative obscurity for their pains while the insouciant and world-resigned Maybeck has become ever more luminous. Is this simply the luminosity that accrues to genius in spite of itself? Was serene self-confidence at the root of Maybecks inclination to wait for the world to come to his door?

That Maybeck enjoyed playing the role of a carefree bohemian was evident in his life-style, his clothing, and his delight in all forms of theater and pageantry. His family celebrated holidays and birthdays in costumes that he designed, and he would transform the house into a make-believe world with backdrops of colored paper. The amateur theatrical productions at the Hillside Club (a mainstay of the Maybeck's social life) and at the Bohemian Club (to which he belonged for over fifty years) provided slightly more public occasions for him to create sets and costumes. Maybeck also designed clothing for his wife, Annie White Maybeck, and himself, drawing the patterns on blueprint paper. For Annie he favored subdued earth tones in simple cuts; for his own everyday wear he designed high-waisted trousers that did away with the need for a vest. After he grew bald in middle age, he wore a beret or tam-o-shanter to ward off colds, and at home he donned a flowing red-velvet robe. Yet he also appreciated good tailoring and bought fine suits when he could afford them. When he could not, he improvised. In 1897, when he and Annie were on their way to Europe to coordinate Phoebe A. Hearst's international architectural competition for the University of California in Berkeley, they were invited to Washington, D.C., to attend Mrs. Hearst's birthday party. The invitation became a daunting challenge when they discovered that Maybeck's old dress suit no longer fit. Lacking the money to purchase new formal attire, they bought a length of red silk instead. When wrapped around Maybeck's middle like a cummerbund, this vivid sash not only covered the gap but intensified his artistic aura.

Maybeck never lost his flair for such improvisation. He turned mishaps such as the malformed surface of the concrete Readers desk in the First Church of Christ, Scientist, into art by transmuting the creases into a frieze of painted irises. He liked to make inexpensive industrial materials serve aesthetic ends as, for example, when he used metal factory-sash in that same church but used a tinted, textured glass and had an extra muntin leaded in to refine the windows proportions. Maybeck's understanding of materials enabled him to use them in unconventional ways that others could not imitate. Although his ideas pervaded the local Arts and Crafts movement, his hyper-individuality inevitably set him apart from all movements. His students benefited from his teaching but not even the most devoted of them, Julia Morgan and Henry Gutterson, captured his wit and ingenuity in their work. During most of his lifetime Maybeck's fame, like that of the Greene brothers and Irving Gill in southern California, remained more or less regional. As the Arts and Crafts movement declined nationwide after World War I, the local allegiance to its principles waned and then vanished almost completely when the 1923 fire in Berkeley destroyed most of its artifacts. After World War II, under the influence of the European International Style, all other movements lost their luster. Like Gill and the Greene brothers, Maybeck was rediscovered in the postwar years, when California boomed and architects from all over the country rushed there to practice. Admiration for these regional geniuses was focused mainly on aspects of their work--structural expression and cubistic form, for example—that could be linked to the aesthetics of the modern movement. Yet, in spite of the romantic eclecticism evident in many of his buildings (and conveniently overlooked), Maybeck's fame began to increase. After he received the American Institute of Architects highest honor, the Gold Medal, in 1951, his national reputation was secure; and with the rise of pluralism in architectural taste in recent decades, the appreciation of Maybeck's work has spread around the world.

The destruction in the 1923 Berkeley fire of at least thirteen buildings from Maybeck's most active years has destroyed the continuity of his work, which would have promoted a better understanding of how his ideas had evolved. Only 150-60 of Maybeck's designs for individual buildings were ever built (there were about 50 unbuilt projects), and only a few were outside the Bay Area. Despite his having had an office in San Francisco for most of his career, which lasted for fifty-three years or so, only about a dozen buildings that Maybeck designed for clients there were built, and several of those have been destroyed or altered. A half-dozen or so of his buildings were constructed in southern California (most of them for Earle C. Anthony), and a few survive in locations north of the Bay Area. Of the several plans for college campuses, company towns, and other large-scale developments that Maybeck designed, the only one that was carried out was for the campus and buildings of Principia College in Elsah, Illinois, which he worked on at the end of his career, from 1930 to 1938, in association with Julia Morgan. After reorganizing his office in 1921 to limit his responsibility to the design phase of projects, Maybeck associated with other architects who took charge of the construction process. Thus he no longer intervened personally in the crafting of the buildings he designed, as he had early in his career, and although it cannot be said that he cared less about them, the delightful improvisations that appear in his earlier buildings are absent from the later ones, except those executed for his family.

Color played an increasingly painterly role in Maybeck's work; indeed, few architects have used color more expressionistically. He stained wooden structural members with orange, red, or green; mixed pigments with stucco for walls; and liked to paint doors and window sashes Prussian blue, sometimes tinting the shaded parts with purple to deepen the tone of the shadow. He also liked to use vivid colors as decorative accents--for example, in the red backing for some of the light fixtures and the doorbell surround in the Roos house (plate 4) and in the gold and bright blue stenciled motifs on the structural members of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley (plate 5). In talking to Dorothy Joralemon about the design of the Joralemon's house in 1923, Maybeck said that too much architecture was sober and drab, and he asked if she would prefer "a white house resembling a bird that has just dropped down on your hilltop, or an earth-colored one that seems to rise out of it." When she chose the latter, Maybeck invited her to participate in the process of spattering the walls with colored stucco. Four pails of wet stucco were prepared, each tinted with a different hue—pale chrome yellow, deep ocher, Venetian red, and gray—and each painter was given a whisk broom with which to flick the stucco onto the walls. Maybeck directed the operation like a maestro: "Red here. Ochre there. Now lighten with yellow. Now soften with gray." When the job was finished, he announced approvingly that the walls vibrated.

Another source of color that Maybeck considered important in designing buildings was landscaping, in which flowering plants, shrubs, and trees were prominent, and lamentably fugitive, components. The planters and trellises that he attached to his buildings testify to his desire to integrate his structure into the landscape, but almost no evidence remains of his intentions for the landscaping of his buildings. Although, for example, he specified pink geraniums for the rooftop planters of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, and bougainvillea and blue hydrangeas for its garden, only the wisteria that covers the trellis outside the great west window has survived (plate 79). In his 1906-7 booklet on hillside building, written for the Hillside Club, Maybeck recommended neighborhood cooperation in landscaping so that blocks were systematically planted: "not fifty feet of pink geraniums, twenty-five of nasturtiums, fifty of purple verbena, but long restful lines, big, quiet masses,—here a roadside of grey olive topped with purple plum, there a line of willows dipped in flame of ivy covered walls,—long avenues of trees with houses …hidden behind a foreground of shrubbery."

Maybeck's concern for architecture focused on a larger scale than the individual building. His training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts nurtured his belief that architecture made its greatest contribution to art and life at the level of urban or civic design, and throughout his career he pursued commissions for major developments. He entered several competitions—the largest of which was for a city plan for Canberra, Australia, in 1911—but without success. Nor did he manage to build the major parts of his plan for the company town of Brookings, Oregon, or to realize his general plan for Mills College. That Maybeck is known chiefly for residential design says more about the opportunities that came his way than about any preference he had for domestic architecture. As for designing large buildings for office use, he appears never even to have been considered for such a commission. The aspects of his personality that endeared him to the proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement doubtless had the opposite effect on the business community. But if Maybeck's bohemianism alarmed those who had commissions for corporate buildings to dispense, he seems not to have been embittered by this lack of notice. When he could not test his ideas through commissions, Maybeck often realized them on smaller projects of his own by mustering up a crew and doing the work himself. Or he committed his dreams to paper in the beautiful drawings that he delighted in doing until the end of his life.

Maybeck launched his practice by designing a series of innovative houses located in a highly visible scenic setting in the Berkeley hills not far from where he lived. The client for the first of these houses (and later his ardent protégé and publicizer) was Charles Keeler, someone he had met by chance on the commuter ferry from Berkeley to San Francisco. Another fortuitous event, Maybeck's presentation to Phoebe Apperson Hearst of a hastily executed sketch for the Hearst Memorial Mining Building on the Berkeley campus, led to his supervising the international competition to select a campus plan for the university. An equally capricious process led to one of Maybeck's greatest commissions: the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (plate 90). The palace was not only everyone's favorite while the fair was in progress, it was the only building complex to be preserved after the fair closed. Such achievements must have helped to balance the disappointments that Maybeck suffered in most of his large-scale projects…

Introduction

Nearly everyone who has written about Bernard Maybeck has described him as naive, even calling him the Great Naïf, as though he had reached a pinnacle of otherworldliness. Yet this benign genie, regarded by even his fellow architects as a crank and a dreamer, instigated and achieved projects with a lasting value that eluded more grounded and practical men. Other talented architects, who were nobody's fools and who did not spare themselves in pursuit of influence and fame, gained relative obscurity for their pains while the insouciant and world-resigned Maybeck has become ever more luminous. Is this simply the luminosity that accrues to genius in spite of itself? Was serene self-confidence at the root of Maybecks inclination to wait for the world to come to his door?

That Maybeck enjoyed playing the role of a carefree bohemian was evident in his life-style, his clothing, and his delight in all forms of theater and pageantry. His family celebrated holidays and birthdays in costumes that he designed, and he would transform the house into a make-believe world with backdrops of colored paper. The amateur theatrical productions at the Hillside Club (a mainstay of the Maybeck's social life) and at the Bohemian Club (to which he belonged for over fifty years) provided slightly more public occasions for him to create sets and costumes. Maybeck also designed clothing for his wife, Annie White Maybeck, and himself, drawing the patterns on blueprint paper. For Annie he favored subdued earth tones in simple cuts; for his own everyday wear he designed high-waisted trousers that did away with the need for a vest. After he grew bald in middle age, he wore a beret or tam-o-shanter to ward off colds, and at home he donned a flowing red-velvet robe. Yet he also appreciated good tailoring and bought fine suits when he could afford them. When he could not, he improvised. In 1897, when he and Annie were on their way to Europe to coordinate Phoebe A. Hearst's international architectural competition for the University of California in Berkeley, they were invited to Washington, D.C., to attend Mrs. Hearst's birthday party. The invitation became a daunting challenge when they discovered that Maybeck's old dress suit no longer fit. Lacking the money to purchase new formal attire, they bought a length of red silk instead. When wrapped around Maybeck's middle like a cummerbund, this vivid sash not only covered the gap but intensified his artistic aura.

Maybeck never lost his flair for such improvisation. He turned mishaps such as the malformed surface of the concrete Readers desk in the First Church of Christ, Scientist, into art by transmuting the creases into a frieze of painted irises. He liked to make inexpensive industrial materials serve aesthetic ends as, for example, when he used metal factory-sash in that same church but used a tinted, textured glass and had an extra muntin leaded in to refine the windows proportions. Maybeck's understanding of materials enabled him to use them in unconventional ways that others could not imitate. Although his ideas pervaded the local Arts and Crafts movement, his hyper-individuality inevitably set him apart from all movements. His students benefited from his teaching but not even the most devoted of them, Julia Morgan and Henry Gutterson, captured his wit and ingenuity in their work. During most of his lifetime Maybeck's fame, like that of the Greene brothers and Irving Gill in southern California, remained more or less regional. As the Arts and Crafts movement declined nationwide after World War I, the local allegiance to its principles waned and then vanished almost completely when the 1923 fire in Berkeley destroyed most of its artifacts. After World War II, under the influence of the European International Style, all other movements lost their luster. Like Gill and the Greene brothers, Maybeck was rediscovered in the postwar years, when California boomed and architects from all over the country rushed there to practice. Admiration for these regional geniuses was focused mainly on aspects of their work--structural expression and cubistic form, for example—that could be linked to the aesthetics of the modern movement. Yet, in spite of the romantic eclecticism evident in many of his buildings (and conveniently overlooked), Maybeck's fame began to increase. After he received the American Institute of Architects highest honor, the Gold Medal, in 1951, his national reputation was secure; and with the rise of pluralism in architectural taste in recent decades, the appreciation of Maybeck's work has spread around the world.

The destruction in the 1923 Berkeley fire of at least thirteen buildings from Maybeck's most active years has destroyed the continuity of his work, which would have promoted a better understanding of how his ideas had evolved. Only 150-60 of Maybeck's designs for individual buildings were ever built (there were about 50 unbuilt projects), and only a few were outside the Bay Area. Despite his having had an office in San Francisco for most of his career, which lasted for fifty-three years or so, only about a dozen buildings that Maybeck designed for clients there were built, and several of those have been destroyed or altered. A half-dozen or so of his buildings were constructed in southern California (most of them for Earle C. Anthony), and a few survive in locations north of the Bay Area. Of the several plans for college campuses, company towns, and other large-scale developments that Maybeck designed, the only one that was carried out was for the campus and buildings of Principia College in Elsah, Illinois, which he worked on at the end of his career, from 1930 to 1938, in association with Julia Morgan. After reorganizing his office in 1921 to limit his responsibility to the design phase of projects, Maybeck associated with other architects who took charge of the construction process. Thus he no longer intervened personally in the crafting of the buildings he designed, as he had early in his career, and although it cannot be said that he cared less about them, the delightful improvisations that appear in his earlier buildings are absent from the later ones, except those executed for his family.

Color played an increasingly painterly role in Maybeck's work; indeed, few architects have used color more expressionistically. He stained wooden structural members with orange, red, or green; mixed pigments with stucco for walls; and liked to paint doors and window sashes Prussian blue, sometimes tinting the shaded parts with purple to deepen the tone of the shadow. He also liked to use vivid colors as decorative accents--for example, in the red backing for some of the light fixtures and the doorbell surround in the Roos house (plate 4) and in the gold and bright blue stenciled motifs on the structural members of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley (plate 5). In talking to Dorothy Joralemon about the design of the Joralemon's house in 1923, Maybeck said that too much architecture was sober and drab, and he asked if she would prefer "a white house resembling a bird that has just dropped down on your hilltop, or an earth-colored one that seems to rise out of it." When she chose the latter, Maybeck invited her to participate in the process of spattering the walls with colored stucco. Four pails of wet stucco were prepared, each tinted with a different hue—pale chrome yellow, deep ocher, Venetian red, and gray—and each painter was given a whisk broom with which to flick the stucco onto the walls. Maybeck directed the operation like a maestro: "Red here. Ochre there. Now lighten with yellow. Now soften with gray." When the job was finished, he announced approvingly that the walls vibrated.

Another source of color that Maybeck considered important in designing buildings was landscaping, in which flowering plants, shrubs, and trees were prominent, and lamentably fugitive, components. The planters and trellises that he attached to his buildings testify to his desire to integrate his structure into the landscape, but almost no evidence remains of his intentions for the landscaping of his buildings. Although, for example, he specified pink geraniums for the rooftop planters of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, and bougainvillea and blue hydrangeas for its garden, only the wisteria that covers the trellis outside the great west window has survived (plate 79). In his 1906-7 booklet on hillside building, written for the Hillside Club, Maybeck recommended neighborhood cooperation in landscaping so that blocks were systematically planted: "not fifty feet of pink geraniums, twenty-five of nasturtiums, fifty of purple verbena, but long restful lines, big, quiet masses,—here a roadside of grey olive topped with purple plum, there a line of willows dipped in flame of ivy covered walls,—long avenues of trees with houses …hidden behind a foreground of shrubbery."

Maybeck's concern for architecture focused on a larger scale than the individual building. His training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts nurtured his belief that architecture made its greatest contribution to art and life at the level of urban or civic design, and throughout his career he pursued commissions for major developments. He entered several competitions—the largest of which was for a city plan for Canberra, Australia, in 1911—but without success. Nor did he manage to build the major parts of his plan for the company town of Brookings, Oregon, or to realize his general plan for Mills College. That Maybeck is known chiefly for residential design says more about the opportunities that came his way than about any preference he had for domestic architecture. As for designing large buildings for office use, he appears never even to have been considered for such a commission. The aspects of his personality that endeared him to the proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement doubtless had the opposite effect on the business community. But if Maybeck's bohemianism alarmed those who had commissions for corporate buildings to dispense, he seems not to have been embittered by this lack of notice. When he could not test his ideas through commissions, Maybeck often realized them on smaller projects of his own by mustering up a crew and doing the work himself. Or he committed his dreams to paper in the beautiful drawings that he delighted in doing until the end of his life.

Maybeck launched his practice by designing a series of innovative houses located in a highly visible scenic setting in the Berkeley hills not far from where he lived. The client for the first of these houses (and later his ardent protégé and publicizer) was Charles Keeler, someone he had met by chance on the commuter ferry from Berkeley to San Francisco. Another fortuitous event, Maybeck's presentation to Phoebe Apperson Hearst of a hastily executed sketch for the Hearst Memorial Mining Building on the Berkeley campus, led to his supervising the international competition to select a campus plan for the university. An equally capricious process led to one of Maybeck's greatest commissions: the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (plate 90). The palace was not only everyone's favorite while the fair was in progress, it was the only building complex to be preserved after the fair closed. Such achievements must have helped to balance the disappointments that Maybeck suffered in most of his large-scale projects…

Textul de pe ultima copertă

Gracefully written and brilliantly illustrated, this handsome new volume captures the vision, the wit, and the down-to-earth inventiveness of one of the most influential and beloved architects of the early twentieth century.