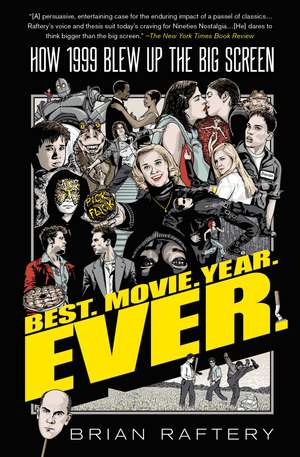

Best. Movie. Year. Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen

Autor Brian Rafteryen Limba Engleză Paperback – apr 2020

In 1999, Hollywood as we know it exploded: Fight Club. The Matrix. Office Space. Election. The Blair Witch Project. The Sixth Sense. Being John Malkovich. Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. American Beauty. The Virgin Suicides. Boys Don’t Cry. The Best Man. Three Kings. Magnolia. Those are just some of the landmark titles released in a dizzying movie year, one in which a group of daring filmmakers and performers pushed cinema to new limits—and took audiences along for the ride. Freed from the restraints of budget, technology, or even taste, they produced a slew of classics that took on every topic imaginable, from sex to violence to the end of the world. The result was a highly unruly, deeply influential set of films that would not only change filmmaking, but also give us our first glimpse of the coming twenty-first century. It was a watershed moment that also produced The Sopranos; Apple’s AirPort; Wi-Fi; and Netflix’s unlimited DVD rentals.

“A spirited celebration of the year’s movies” (Kirkus Reviews), Best. Movie. Year. Ever. is the story of not just how these movies were made, but how they re-made our own vision of the world. It features more than 130 new and exclusive interviews with such directors and actors as Reese Witherspoon, Edward Norton, Steven Soderbergh, Sofia Coppola, David Fincher, Nia Long, Matthew Broderick, Taye Diggs, M. Night Shyamalan, David O. Russell, James Van Der Beek, Kirsten Dunst, the Blair Witch kids, the Office Space dudes, the guy who played Jar-Jar Binks, and dozens more. It’s “the complete portrait of what it was like to spend a year inside a movie theater at the best possible moment in time” (Chuck Klosterman).

Preț: 117.71 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 177

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.53€ • 23.27$ • 18.75£

22.53€ • 23.27$ • 18.75£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501175398

ISBN-10: 1501175394

Pagini: 416

Ilustrații: b&w chapter opener illustrations thru-out

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501175394

Pagini: 416

Ilustrații: b&w chapter opener illustrations thru-out

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Brian Raftery is a senior writer for Wired magazine, where he covers film, television, and internet culture. His work has also appeared in GQ, Rolling Stone, Esquire, and New York magazine. The author of Best. Movie. Year. Ever., he lives in Burbank, California, with his wife and daughters.

Extras

Best. Movie. Year. Ever.

DECEMBER 31, 1999

It was New Year’s Eve, and on a private beach resort in Mexico, a handful of couples had gathered to celebrate the end of the century. Brad Pitt and his then girlfriend, Jennifer Aniston, were there. So were director David Fincher and his partner, the film producer Ceán Chaffin. For the last few months, they’d watched the world react with fury to Fight Club, Pitt and Fincher’s bruising new tale of chaos-loving alpha-maniacs. The movie was an assaultive big-budget takedown of late-nineties values with a catchphrase so recognizable—“The first rule of fight club is: You do not talk about fight club”—that Aniston had spoofed it while hosting Saturday Night Live that fall. But although people had talked about Fight Club, often angrily, few moviegoers had actually shown up to watch it. The film had barely earned back half its budget at the box office, making it among the biggest commercial failures of the two men’s careers. By the time the group arrived in Mexico, says Fight Club producer Chaffin, “we were still licking our wounds.”

Joining them on the getaway was Marc Gurvitz, a high-powered manager who worked with Aniston and who’d come to the island with his then fiancée. He remembers the early moments of their trip as being largely relaxed—so much so that he felt comfortable enough to prank his companions, putting fake snakes and scorpions in their beds. But Gurvitz was also a bit nervous about the decade coming to a close. Like millions of others, he’d heard the warnings: about how at midnight that night—just as the twenty-first century was grabbing a rave whistle and starting its hundred-year party—a global cataclysm would supposedly reboot civilization. Skylines would dim. Bank accounts would flatline. Things would break down. It was a save-the-date disaster with a strict deadline and a catchy name: Y2K, short for “Year 2000.” “Everyone was afraid that the world was going to end,” says Gurvitz. “It was pretty scary.” Even Fight Club had picked up on that premillennial tension, its final scene consisting of a series of credit card company headquarters crumbling to the ground—a chance for society to start anew. As Pitt later recalled, the mood in 1999 was one of uncertainty: “What was going to happen?” the actor asked. “People weren’t gonna go on trips, even, because they were afraid.”

Pitt and his fellow vacationers had nonetheless braved it to their island resort, where they’d be hours away from the nearest city. No matter what went down when the clock struck twelve, they’d largely be on their own. As the moment drew closer, Gurvitz and the others assembled for margaritas near the beach. Just as the new year was about to arrive, though, the group was thrown into darkness. “It was three . . . two . . . one . . . and then all the power in the entire place went out,” says Fincher. “There was nervous laughter, like, ‘Y2K, ha-ha-ha!’?”

The group decided to relocate to a nearby bonfire. “All of a sudden,” remembers Gurvitz, “two jeeps in the distance come out of the dark with their lights flashing.” It was a team of local federales, many traveling in a large black vehicle with the word policía on it. “There were three nineteen-year-old kids with M16s in the back,” says Fincher. “They came over the hill, pulled in, and got out and went running into the main lobby.”

Eventually the hotel concierge emerged, saying there was a problem with the plane the group had chartered to the island, and that someone needed to come with the police. The task would fall on Gurvitz, who was confused—in the dark in every way. Before he knew it, Gurvitz’s hands were being pulled behind his Hawaiian-print shirt and placed in cuffs. The federales were speaking to him in Spanish, which Gurvitz couldn’t understand. But he realized they were taking him to jail. “Pitt walks up to the guys,” Gurvitz recalls, “and gets in their face: ‘Hey! You can’t come into a resort and take an American citizen!’?” Unimpressed, the officials threw Pitt to the ground. “Brad’s saying, ‘This is outrageous! You’ll hear from my attorneys!’?” says Fincher, who volunteered to go with Gurvitz.

As they pulled away from the beach, Gurvitz looked back at his party, unsure of what would happen next. “His fiancée’s freaking out, in tears,” Pitt said. “They’re driving off with him into the pitch blackness, and he’s surrounded by guys with [guns].”

Gurvitz watched as his friends grew smaller in the distance. Just as he’d feared, something had gone wrong. Something had broken down.

Oh my fucking God, he thought.

• • •

In the final months of the twentieth century, millions of Americans believed we were headed toward a reckoning—so much so, they spent what was left of the nineties gearing up for a meltdown. Some converted their homes into DIY fallout shelters, stocking them with canned chow mein, toilet paper, or three-hundred-gallon waterbeds (which they could pop open and drink from in the event of a drought). Others prepared by buying guns—lots of guns. Less than two weeks before the arrival of the new millennium, the FBI received 67,000 gun sale background check requests in a single day, setting a new record. Many of those applicants had no doubt become obsessed with the “millennium bug”—a data hiccup that would supposedly cause thousands of computers to simultaneously collapse, unable to recognize the changeover from 12/31/99 to 01/01/00.

The US government, along with several corporations, had spent an estimated $100 billion combined to upgrade their machines in time. In Silicon Valley, Y2K worries were so pitched that Apple head Steve Jobs commissioned a Super Bowl ad featuring HAL, the creepily sentient computer system from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi trip 2001: A Space Odyssey. The commercial finds HAL speaking from the future, where he apologizes for the chaos caused by the changeover. “When the new millennium arrived,” HAL says coldly, “we had no choice but to cause a global economic destruction.” (The only computers to avoid the meltdown, according to HAL, were made by Apple.)

The famously private Kubrick would later call Jobs, telling him how much he had enjoyed the spot. Yet some in the tech industry didn’t find the prospect of Y2K funny. There was a real fear that, no matter what we did to prepare, Prince’s famed pop prophecy was bound to come true: “Two-thousand-zero-zero/party over/oops/out of time.” “I’ve seen how fragile so many software systems are—how one bug can bring them down,” a longtime programmer told Wired. He’d retreated into the California desert and built a solar-powered, fenced-off New Year’s Eve hideaway (he also bought his very first gun, just in case). Others saw Y2K as a potential biblical event: in Jerry Falwell’s home video Y2K: A Christian’s Survival Guide to the Millennium Bug, available for just under $30 a pop, the smug televangelist—last seen warning his flock about the gay agenda of the Teletubbies—cautioned that Y2K could be “God’s instrument to shake this nation, to humble this nation” (he also advised loading up on ammo, just in case).

Whether they were freaked out by technology or theology, many of the end-timers shared a common tut-tutting anxiety: namely, that we’d advanced a bit too much during the twentieth century, sacrificing our humanity in favor of ease and desire. And now retribution was due, whether it took the form of an act of God or a downloadable rapture. As one mother of three sighed in the December 31, 1999, edition of the New York Times, “It just seems like the end is getting closer.”

If the collapse of civilization was upon us, the timing couldn’t have been worse. In 1999, the United States was in the midst of an unexpected comeback. The decade had begun with a recession, pivoted to a foreign war, and nearly culminated in a president’s removal from office. Now, across the country, people were indulging in a wave of contagious optimism. You could see that giddiness on Wall Street, where, throughout 1999, the Dow Jones, the NASDAQ, and the New York Stock Exchange had all experienced hypercharged highs. You could sense it on the radio, where the gloom raiders who’d soundtracked so much of the decade had been replaced by teen cutie pies and loca-living pop stars. You could even experience it via the digital dopamine rush of the internet, which was still in utero—and still populated by weirdos—but which had the potential to make everyone smarter or richer than they’d ever imagined. In just a few years, Jeff Bezos had transformed Amazon.com from an online bookseller to an all-encompassing twenty-four-hour shopping mall (Bezos’s awkwardly smiling face would be stuffed into a cardboard box for Time’s 1999 Person of the Year cover). And before the year was over, the recently launched movies-by-mail company Netflix would raise $30 million in funding, and introduce its first monthly DVD-rental plan.

But the surest way to feel that static-electric zap of possibility was to walk into a movie theater in 1999—the most unruly, influential, and unrepentantly pleasurable film year of all time.

It began with January’s Sundance Film Festival debut of The Blair Witch Project—a jumpy, star-free vomit comet—and ended with the December deluge of Magnolia, the movie-ist movie of the year, featuring a 188-minute running time, a plague of frogs, and the sight of megaceleb Tom Cruise crotch thrusting his way to catharsis. In between came a collision of visions, all of them thrillingly singular: The Matrix. The Sixth Sense. Election. Rushmore. Office Space. The Virgin Suicides. Boys Don’t Cry. Run Lola Run. The Insider. Three Kings. Being John Malkovich. Many of those films—along with Star Wars: Episode 1—The Phantom Menace, the most unpopular popular movie of the year, if not of all time—would break the laws of narrative, form, and even bullet-time–bending physics. In 1999, “The whole concept of ‘making a movie’ got turned on its head,” proclaimed writer Jeff Gordinier in a November cover story in Entertainment Weekly. “The year when all the old, boring rules about cinema started to crumble.”

Yet for all their audacity, the movies of 1999 were also sneakily personal, luring viewers with promises of high-end thrills or movie star grandeur—only to turn the focus back on the audience, forcing them to consider all sorts of questions about identity and destiny: Who am I? Who else could I be? The body-bending thrills of The Matrix; the white-collar uprisings of Fight Club and Office Space; the self-seeking voyages of Being John Malkovich and Boys Don’t Cry; the Xbox-on-ecstasy story line swaps of Go and Run Lola Run. Each was a glimpse of not just an alternate world but an alternate you—maybe even the real you. As exhilarating as it was to walk into a theater that year, it felt ever better to float on out, alive with a sense of potential, the end credits hinting at a new start. Maybe something amazing was awaiting us on the other side of 1999.

“It was a new century—the beginning of a new story,” says director M. Night Shyamalan, whose spiritual shocker The Sixth Sense would become 1999’s second-highest-grossing movie. “And it was a time for original voices. The people paying to make the movies—and the people going to the movies—all said, ‘We don’t need to know where we are going. We trust the filmmaker.’?”

Studio executives have long lusted for the so-called four-quadrant movie—a film that appeals equally to men and women, young and old. But 1999 was a four-quadrant year: it had something for everyone. The domestic box office pulled in nearly $7.5 billion, and although some of that was fueled by franchise entries such as Toy Story 2 and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, many of the most successful films of 1999 were complete originals: The Matrix, The Sixth Sense, American Beauty, American Pie, Notting Hill, and The Blair Witch Project all made more than $100 million, even though none was based on a comic book series, a TV show, or a real-life witch (despite what some Blair viewers may have believed). “One thing I learned from my farmer friends is that, every twenty or thirty years, you get a good harvest,” says actor Luis Guzmán, who appeared in Magnolia and The Limey (and who spends a good amount of time in rural Vermont). “And that’s how I look at the movies from 1999.”

Film dictated the conversation that year—which is impressive when you consider just how satisfyingly overstuffed 1999 was. Top-forty pop had just been reignited by MTV’s Total Request Live and such crazy-sexy-cruel mainstays as Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Eminem, and Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst. And the January arrival of the mob drama The Sopranos—the most must-see TV show in a year that was full of them, from The West Wing to Freaks and Geeks—heralded a small-screen overthrow that would only become more pronounced in the years to come.

But in 1999, the movies were still the higher power of popular culture. You had to see Fight Club—or American Beauty or Rushmore or Magnolia—if for no other reason than to see what everyone else was talking about.

• • •

There’d been other years like this, of course—ones in which film took an almost teleportative leap forward, reinventing and reviving itself in front of our very eyes. In 1939, the triple-headed tornado of The Wizard of Oz, Gone With the Wind, and Stagecoach reimagined what big-screen storytelling could look like. The year 1967 saw the generation-defining (and generation-dividing) debuts of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, while a decade later came Star Wars, Annie Hall, and Eraserhead—a trio of films that are still being ripped off and riffed upon today. Even a relatively shallow season like 1985, which occurred smack in the middle of the escapist Reagan era, could find room for sneak-attack thrills such as Brazil, After Hours, and Desperately Seeking Susan. Pretty much every movie year is a good one, even if you have to do some searching to find the masterworks or minimovements.

But in 1999, sixty years after Dorothy dropped a house into Oz, a group of filmmakers started their own Technicolor riot, one that took place right on the fault line of two centuries, and drew power and inspiration from both. Many of the directors, writers, and executives from that year were de facto film scholars—some educated at NYU or USC, some by VHS—and their movies shared a reverence for what had come before. It wasn’t hard to connect The Matrix’s reality-revealing red pill to Oz’s yellow brick road; or the fax-and-mouse games of The Insider to the hush-hush muckraking of All the President’s Men; or the adrift suburban teens of The Virgin Suicides to the ones in Sixteen Candles.

“We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us,” is the oft spoken mantra of Magnolia, and the past was everywhere you looked in 1999—as if all of those previous cinematic epochs had been compressed, burned onto a zip drive, and passed around from one filmmaker to the next. The movies that loomed largest over 1999 were the ones produced between 1967 and 1979—a period that saw an unparalleled, and today unthinkable, combination of high-IQ thrillers, confrontational comedies, and existentially troubled dramas. For many late-nineties directors, the so-called Easy Riders, Raging Bulls filmmakers—named after Peter Biskind’s myth-making 1998 book—were the big screen’s own greatest generation, executing wild ideas with big-studio backing. “They were movies that dealt with the texture of real life,” says director Alison Maclean, whose 1999 druggie travelogue Jesus’ Son was influenced by such rough-and-tumble seventies pictures as The Long Goodbye and The Panic in Needle Park. “There’s a soulfulness to those films, and a sense of spiritual crisis—of something being broken.”

Decades later, that unvarnished, unfulfilled sense of purpose-driven ennui crept back into movie theaters. Sometimes the links between the movies of 1999 and the films of the Nixon/Carter years were atmospheric: the Gulf War–set Three Kings echoed such combative black comedies as M*A*S*H and Catch-22, while the doomed heartland romance in Boys Don’t Cry recalled the one in Badlands. Other times, the filmmakers had consciously sought to forge connections with the past. Pedro Almodóvar’s Oscar-winning All About My Mother—a vibrant heartbreaker about love and theater—was inspired by John Cassavetes’s 1977 drama Opening Night. Before shooting Magnolia, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson held cast and crew screenings of the 1976 tragicomedy Network for inspiration. And no movie seduced quite as many filmmakers as 1967’s The Graduate, the quintessential tale of rudderless youth that informed everything from Fight Club to Rushmore to American Pie.

But that reverence toward film’s history was matched by a desire to fuck around with its future. Everything was up for grabs in 1999—visually, narratively, thematically. The old “It’s like movie X meets movie Y” descriptors simply didn’t compute anymore. “I remember looking at that lineup in ’99 and thinking, ‘Name me any year between 1967 and 1975 that had more really original young filmmakers tapping into the zeitgeist,’?” says Fight Club’s Edward Norton. “I would stack that year up against any other.” Adds Sam Mendes, whose suburban nightmare debut, American Beauty, earned Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture: “It’s astonishing how many different genres were being redefined. Is The Sixth Sense a horror movie, a thriller, or a ghost story? What is Fight Club? What is Being John Malkovich? Even American Beauty—is it a coming-of-age tale or a fantasy? Something was definitely shifting.”

It wasn’t just genres that were evolving in 1999. Storytelling itself was in the middle of a mutation. Aided by quick-moving digital editing machines and cheap video cameras, filmmakers ripped up and remixed the century-old rules of cinema, screwing with time, perspective, and expectations. Movies such as the madcap Go or Steven Soderbergh’s crisp neo-noir The Limey treated traditional story beats like Tetris blocks, stacking them atop or snugging them around one another—or letting them fall, just to see what form they might take. And The Matrix and The Phantom Menace used immersive digital effects to render entire artificial worlds, which could then be altered with a computer; it was almost as if the filmmakers could actually reach right into the frame and reorder their onscreen universe.

Audience members—who’d spent the nineties retraining their brains to absorb everything from reality TV to Resident Evil to pixel-dusted webcam videos—were willing to play along, even if they didn’t always know what they were getting into. “The entire narrative structure of movies exploded,” notes Lisa Schwarzbaum, an Entertainment Weekly film critic from 1991 to 2013. “You could tell stories in pieces, or backward. You could be lost at the beginning, or you could repeat things, or you could have people flying around the Matrix.”

At times the movies of 1999 felt like part of some mass insurrection, one overseen by three overlapping generations of idiosyncratic filmmakers. “These are very eclectic, interesting directors, who have all stood the test of ‘Do you have anything really to say?’?” notes Fincher, who refers to his peers as “precocious, inspired lunatics.” “Speed was one of the biggest movies that had ever been made at that time—but was [director] Jan de Bont a voice? No. These directors we’re talking about all have something that stains what they do.”

Some of the Class of ’99—including Eyes Wide Shut’s Stanley Kubrick and The Thin Red Line’s Terrence Malick—were returning to moviemaking for the first time in decades. Others, such as Michael Mann (The Insider), had been revered as sly, stylish troublemakers since at least the eighties. Then there were the upstarts who’d begun their careers in the world of lower-budget indies: Wes Anderson (Rushmore), the Wachowskis (The Matrix), and Alexander Payne (Election), among several others. In 1999, they’d all be joined by such nü-brat debutantes as Sofia Coppola, Spike Jonze, and Kimberly Peirce. “We were de facto not the establishment,” Peirce says of her contemporaries. “A bunch of us were reacting to the bigger and more actiony movies of the nineties, saying, ‘That’s not how I think—but I have this story that I really love, one that’s smaller and weirder.’?”

Nearly all the filmmakers of 1999 opted to tell stories that were similarly personal (even if they weren’t always quite so small-scale). And they often subverted the expectations of their own fans. Few would have guessed, for example, that Magnolia’s Paul Thomas Anderson would follow his sweaty porn-biz odyssey Boogie Nights with a sober drama about cancer and interconnectivity. Nor would anyone have predicted that David Lynch—who’d spent the decade making such provocations as Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me—would close out the nineties with a film like The Straight Story, a G-rated, Disney-released tale of an elderly man traveling cross-country on a tractor to visit his ailing brother. If the writers and directors of 1999 shared one unspoken trait, it was the ambition to make something no one had seen before. “Young and older generations came together in this exploratory way,” says Run Lola Run writer-director Tom Tykwer. “There was this beautiful competition between experimental filmmaking and the so-called established filmmaking. But they were also giving each other fire and enthusiasm.”

And they were doing so in a year in which some people were penciling the apocalypse on their calendar, just in case. “There was so much going on about Y2K, and so much talk about computers going haywire, that it even reached down to the people who thought it was total malarkey,” says The Straight Story cowriter and editor Mary Sweeney. “It was the end of a very dramatic decade.”

While the nineties would later be revised by some as a sort of pre-9/11 paradise, the period had in fact been marked by social and political tumult: the beating of Rodney King, the battle over Anita Hill, and terrorist attacks like the bombing in Oklahoma City. By the time 1999 arrived, it felt like anything could happen. “People forget how much anxiety there was,” says Norton. “It was the anxiety of Gen-X entering adulthood, and it had real collateral. It’s expressed in Magnolia, it’s expressed in Fight Club, and it’s expressed in Being John Malkovich: that anxiety about being asked to enter a world that seemed a little bit uninviting.”

But it’s Norton’s Fight Club character—an unnamed solace seeker who dramatically reboots his own life—who discovers the hidden promise of this new era of uncertainty: “Losing all hope was freedom,” he says, and many of the filmmakers and performers from the 1999 movies could relate. Thrown together at the end of the century, and at the height of their industry’s pop-culture powers, they’d been liberated from constraints of budget and technology—and sometimes even the wishes of their bosses—to make whatever movie they wanted, however they wanted. “Maybe it was the rush of everyone thinking about the end of the world,” says Rick Famuyiwa, the writer-director of the 1999 comedy-drama The Wood. “We felt we had to get our voices heard before we all disappeared.”

• • •

And so, as the clocks drew closer to midnight on New Year’s Eve and the Y2K buzzkillers waited it out from their homemade bunkers, the rest of the world prepared to party into a new age. At the White House, President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton hosted a massive gala, as well as a musical concert emceed by Will Smith, he of the recent kinda hit “Will 2K” (“What’s gonna happen/Don’t nobody know/We’ll see when the clock hits twelve-oh-oh”). In Manhattan, nearly a million ball watchers showed up in Times Square—the home of MTV’s studios, where No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani would play R.E.M.’s hyperwordy “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” aided by a grip holding up cue cards.

Meanwhile, at smaller get-togethers across the country, revelers stuck close to friends and family, waiting to make sure the millennium went off without a hitch. Brendan Fraser, star of 1999’s summer hit The Mummy, was in his newly finished home in rainy Los Angeles, watching Tonight Show host Jay Leno fend off the downpour on live television, “looking like a wet cat who was really annoyed,” Fraser says. Shyamalan—no stranger to surprise endings—sat in his Pennsylvania home, keeping an eye on his newborn daughter. Sofia Coppola and her husband, Being John Malkovich director Spike Jonze, gathered for a decadent get-together at her parents’ estate in Napa Valley, California. “If it was the end of the world,” she says, “we were going to do it in style.” And The Matrix’s Joe Pantoliano was at a neighbor’s house in suburban Connecticut, hanging in the laundry room with actor Chazz Palminteri. Pantoliano had stockpiled some valuables for the millennium, just in case. “I’d bought $10,000 worth of silver coins and hid them above the refrigerator,” he says. “If there was any validity to Y2K, I thought I could buy milk and gas and tools.”

Not all of the celebrants that night were quite as concerned about the centennial changeover. Fraser remembers that by December 31, end-times hoopla had gotten so out of hand it was hard to take it seriously: “There’ll be giraffes on fire charging down the street! ATM machines are going to spit cash everywhere!” he jokingly remembers of the warnings.

Yet with an uncertain new decade now closer than ever, it was hard to put such concerns completely out of mind. That night in Los Angeles, Reese Witherspoon, the twenty-three-year-old star of Election and Cruel Intentions, was at a party in Los Angeles, just months after giving birth to her first child. At one point during the festivities, her Cruel Intentions costar (and then husband) Ryan Phillippe took a photo of Witherspoon posing underneath a giant Y2K sign, her hands covering her head. “We were all terrified,” she says.

Meanwhile in Mexico, Marc Gurvitz was heading down a long, darkened road. Fincher, riding with him, noticed the lights had suddenly gone back on at the resort, and asked the gun-toting officials to allow Gurvitz to return to make a phone call. Reluctantly, the driver agreed.

Soon the vehicle was pulling up at the beach—which is where Pitt and the rest of the revelers were waiting. “They’ve all got jeroboams of champagne, and Brad’s wearing this ridiculous gold-sequinned little party hat,” remembers Fincher. The whole thing had been a setup: the power outage, the arrest, even Pitt’s tussling with the federales (“Daniel Day-Lewis would have been awed,” Fincher says of the actor’s performance). After being subjected to Gurvitz’s own practical jokes for days, Fincher and Pitt—the space-monkeys behind Fight Club—had decided to take their revenge, coordinating the stunt with the help of the locals. “It was as harsh as it could be and not be cruel,” says Fincher, still chuckling at the ruse decades later. “Listen, if we could have had gunfire with blanks, we’d have done it, but it was a last-minute thing.” Even Gurvitz eventually laughed, “after I cleaned up my pants,” he says. “It was like Fincher choreographed a movie. That’s how sick these fucking guys are.”

As midnight arrived across the world, millions felt the same way as Gurvitz: They’d been pranked. The meltdown of Y2K never arrived. Computers kept humming; planes remained airborne; bank accounts survived. “Just a whimper, not a bang,” says Fraser.

Y2K was its own kind of phantom menace. We’d spent so much time wondering what the twenty-first century might look like, most of us failed to notice that it had already shown up. And if you wanted to see it, all you had to do was go to the movies.

PROLOGUE

“LOSING ALL HOPE WAS FREEDOM.”

DECEMBER 31, 1999

It was New Year’s Eve, and on a private beach resort in Mexico, a handful of couples had gathered to celebrate the end of the century. Brad Pitt and his then girlfriend, Jennifer Aniston, were there. So were director David Fincher and his partner, the film producer Ceán Chaffin. For the last few months, they’d watched the world react with fury to Fight Club, Pitt and Fincher’s bruising new tale of chaos-loving alpha-maniacs. The movie was an assaultive big-budget takedown of late-nineties values with a catchphrase so recognizable—“The first rule of fight club is: You do not talk about fight club”—that Aniston had spoofed it while hosting Saturday Night Live that fall. But although people had talked about Fight Club, often angrily, few moviegoers had actually shown up to watch it. The film had barely earned back half its budget at the box office, making it among the biggest commercial failures of the two men’s careers. By the time the group arrived in Mexico, says Fight Club producer Chaffin, “we were still licking our wounds.”

Joining them on the getaway was Marc Gurvitz, a high-powered manager who worked with Aniston and who’d come to the island with his then fiancée. He remembers the early moments of their trip as being largely relaxed—so much so that he felt comfortable enough to prank his companions, putting fake snakes and scorpions in their beds. But Gurvitz was also a bit nervous about the decade coming to a close. Like millions of others, he’d heard the warnings: about how at midnight that night—just as the twenty-first century was grabbing a rave whistle and starting its hundred-year party—a global cataclysm would supposedly reboot civilization. Skylines would dim. Bank accounts would flatline. Things would break down. It was a save-the-date disaster with a strict deadline and a catchy name: Y2K, short for “Year 2000.” “Everyone was afraid that the world was going to end,” says Gurvitz. “It was pretty scary.” Even Fight Club had picked up on that premillennial tension, its final scene consisting of a series of credit card company headquarters crumbling to the ground—a chance for society to start anew. As Pitt later recalled, the mood in 1999 was one of uncertainty: “What was going to happen?” the actor asked. “People weren’t gonna go on trips, even, because they were afraid.”

Pitt and his fellow vacationers had nonetheless braved it to their island resort, where they’d be hours away from the nearest city. No matter what went down when the clock struck twelve, they’d largely be on their own. As the moment drew closer, Gurvitz and the others assembled for margaritas near the beach. Just as the new year was about to arrive, though, the group was thrown into darkness. “It was three . . . two . . . one . . . and then all the power in the entire place went out,” says Fincher. “There was nervous laughter, like, ‘Y2K, ha-ha-ha!’?”

The group decided to relocate to a nearby bonfire. “All of a sudden,” remembers Gurvitz, “two jeeps in the distance come out of the dark with their lights flashing.” It was a team of local federales, many traveling in a large black vehicle with the word policía on it. “There were three nineteen-year-old kids with M16s in the back,” says Fincher. “They came over the hill, pulled in, and got out and went running into the main lobby.”

Eventually the hotel concierge emerged, saying there was a problem with the plane the group had chartered to the island, and that someone needed to come with the police. The task would fall on Gurvitz, who was confused—in the dark in every way. Before he knew it, Gurvitz’s hands were being pulled behind his Hawaiian-print shirt and placed in cuffs. The federales were speaking to him in Spanish, which Gurvitz couldn’t understand. But he realized they were taking him to jail. “Pitt walks up to the guys,” Gurvitz recalls, “and gets in their face: ‘Hey! You can’t come into a resort and take an American citizen!’?” Unimpressed, the officials threw Pitt to the ground. “Brad’s saying, ‘This is outrageous! You’ll hear from my attorneys!’?” says Fincher, who volunteered to go with Gurvitz.

As they pulled away from the beach, Gurvitz looked back at his party, unsure of what would happen next. “His fiancée’s freaking out, in tears,” Pitt said. “They’re driving off with him into the pitch blackness, and he’s surrounded by guys with [guns].”

Gurvitz watched as his friends grew smaller in the distance. Just as he’d feared, something had gone wrong. Something had broken down.

Oh my fucking God, he thought.

• • •

In the final months of the twentieth century, millions of Americans believed we were headed toward a reckoning—so much so, they spent what was left of the nineties gearing up for a meltdown. Some converted their homes into DIY fallout shelters, stocking them with canned chow mein, toilet paper, or three-hundred-gallon waterbeds (which they could pop open and drink from in the event of a drought). Others prepared by buying guns—lots of guns. Less than two weeks before the arrival of the new millennium, the FBI received 67,000 gun sale background check requests in a single day, setting a new record. Many of those applicants had no doubt become obsessed with the “millennium bug”—a data hiccup that would supposedly cause thousands of computers to simultaneously collapse, unable to recognize the changeover from 12/31/99 to 01/01/00.

The US government, along with several corporations, had spent an estimated $100 billion combined to upgrade their machines in time. In Silicon Valley, Y2K worries were so pitched that Apple head Steve Jobs commissioned a Super Bowl ad featuring HAL, the creepily sentient computer system from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi trip 2001: A Space Odyssey. The commercial finds HAL speaking from the future, where he apologizes for the chaos caused by the changeover. “When the new millennium arrived,” HAL says coldly, “we had no choice but to cause a global economic destruction.” (The only computers to avoid the meltdown, according to HAL, were made by Apple.)

The famously private Kubrick would later call Jobs, telling him how much he had enjoyed the spot. Yet some in the tech industry didn’t find the prospect of Y2K funny. There was a real fear that, no matter what we did to prepare, Prince’s famed pop prophecy was bound to come true: “Two-thousand-zero-zero/party over/oops/out of time.” “I’ve seen how fragile so many software systems are—how one bug can bring them down,” a longtime programmer told Wired. He’d retreated into the California desert and built a solar-powered, fenced-off New Year’s Eve hideaway (he also bought his very first gun, just in case). Others saw Y2K as a potential biblical event: in Jerry Falwell’s home video Y2K: A Christian’s Survival Guide to the Millennium Bug, available for just under $30 a pop, the smug televangelist—last seen warning his flock about the gay agenda of the Teletubbies—cautioned that Y2K could be “God’s instrument to shake this nation, to humble this nation” (he also advised loading up on ammo, just in case).

Whether they were freaked out by technology or theology, many of the end-timers shared a common tut-tutting anxiety: namely, that we’d advanced a bit too much during the twentieth century, sacrificing our humanity in favor of ease and desire. And now retribution was due, whether it took the form of an act of God or a downloadable rapture. As one mother of three sighed in the December 31, 1999, edition of the New York Times, “It just seems like the end is getting closer.”

If the collapse of civilization was upon us, the timing couldn’t have been worse. In 1999, the United States was in the midst of an unexpected comeback. The decade had begun with a recession, pivoted to a foreign war, and nearly culminated in a president’s removal from office. Now, across the country, people were indulging in a wave of contagious optimism. You could see that giddiness on Wall Street, where, throughout 1999, the Dow Jones, the NASDAQ, and the New York Stock Exchange had all experienced hypercharged highs. You could sense it on the radio, where the gloom raiders who’d soundtracked so much of the decade had been replaced by teen cutie pies and loca-living pop stars. You could even experience it via the digital dopamine rush of the internet, which was still in utero—and still populated by weirdos—but which had the potential to make everyone smarter or richer than they’d ever imagined. In just a few years, Jeff Bezos had transformed Amazon.com from an online bookseller to an all-encompassing twenty-four-hour shopping mall (Bezos’s awkwardly smiling face would be stuffed into a cardboard box for Time’s 1999 Person of the Year cover). And before the year was over, the recently launched movies-by-mail company Netflix would raise $30 million in funding, and introduce its first monthly DVD-rental plan.

But the surest way to feel that static-electric zap of possibility was to walk into a movie theater in 1999—the most unruly, influential, and unrepentantly pleasurable film year of all time.

It began with January’s Sundance Film Festival debut of The Blair Witch Project—a jumpy, star-free vomit comet—and ended with the December deluge of Magnolia, the movie-ist movie of the year, featuring a 188-minute running time, a plague of frogs, and the sight of megaceleb Tom Cruise crotch thrusting his way to catharsis. In between came a collision of visions, all of them thrillingly singular: The Matrix. The Sixth Sense. Election. Rushmore. Office Space. The Virgin Suicides. Boys Don’t Cry. Run Lola Run. The Insider. Three Kings. Being John Malkovich. Many of those films—along with Star Wars: Episode 1—The Phantom Menace, the most unpopular popular movie of the year, if not of all time—would break the laws of narrative, form, and even bullet-time–bending physics. In 1999, “The whole concept of ‘making a movie’ got turned on its head,” proclaimed writer Jeff Gordinier in a November cover story in Entertainment Weekly. “The year when all the old, boring rules about cinema started to crumble.”

Yet for all their audacity, the movies of 1999 were also sneakily personal, luring viewers with promises of high-end thrills or movie star grandeur—only to turn the focus back on the audience, forcing them to consider all sorts of questions about identity and destiny: Who am I? Who else could I be? The body-bending thrills of The Matrix; the white-collar uprisings of Fight Club and Office Space; the self-seeking voyages of Being John Malkovich and Boys Don’t Cry; the Xbox-on-ecstasy story line swaps of Go and Run Lola Run. Each was a glimpse of not just an alternate world but an alternate you—maybe even the real you. As exhilarating as it was to walk into a theater that year, it felt ever better to float on out, alive with a sense of potential, the end credits hinting at a new start. Maybe something amazing was awaiting us on the other side of 1999.

“It was a new century—the beginning of a new story,” says director M. Night Shyamalan, whose spiritual shocker The Sixth Sense would become 1999’s second-highest-grossing movie. “And it was a time for original voices. The people paying to make the movies—and the people going to the movies—all said, ‘We don’t need to know where we are going. We trust the filmmaker.’?”

Studio executives have long lusted for the so-called four-quadrant movie—a film that appeals equally to men and women, young and old. But 1999 was a four-quadrant year: it had something for everyone. The domestic box office pulled in nearly $7.5 billion, and although some of that was fueled by franchise entries such as Toy Story 2 and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, many of the most successful films of 1999 were complete originals: The Matrix, The Sixth Sense, American Beauty, American Pie, Notting Hill, and The Blair Witch Project all made more than $100 million, even though none was based on a comic book series, a TV show, or a real-life witch (despite what some Blair viewers may have believed). “One thing I learned from my farmer friends is that, every twenty or thirty years, you get a good harvest,” says actor Luis Guzmán, who appeared in Magnolia and The Limey (and who spends a good amount of time in rural Vermont). “And that’s how I look at the movies from 1999.”

Film dictated the conversation that year—which is impressive when you consider just how satisfyingly overstuffed 1999 was. Top-forty pop had just been reignited by MTV’s Total Request Live and such crazy-sexy-cruel mainstays as Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Eminem, and Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst. And the January arrival of the mob drama The Sopranos—the most must-see TV show in a year that was full of them, from The West Wing to Freaks and Geeks—heralded a small-screen overthrow that would only become more pronounced in the years to come.

But in 1999, the movies were still the higher power of popular culture. You had to see Fight Club—or American Beauty or Rushmore or Magnolia—if for no other reason than to see what everyone else was talking about.

• • •

There’d been other years like this, of course—ones in which film took an almost teleportative leap forward, reinventing and reviving itself in front of our very eyes. In 1939, the triple-headed tornado of The Wizard of Oz, Gone With the Wind, and Stagecoach reimagined what big-screen storytelling could look like. The year 1967 saw the generation-defining (and generation-dividing) debuts of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, while a decade later came Star Wars, Annie Hall, and Eraserhead—a trio of films that are still being ripped off and riffed upon today. Even a relatively shallow season like 1985, which occurred smack in the middle of the escapist Reagan era, could find room for sneak-attack thrills such as Brazil, After Hours, and Desperately Seeking Susan. Pretty much every movie year is a good one, even if you have to do some searching to find the masterworks or minimovements.

But in 1999, sixty years after Dorothy dropped a house into Oz, a group of filmmakers started their own Technicolor riot, one that took place right on the fault line of two centuries, and drew power and inspiration from both. Many of the directors, writers, and executives from that year were de facto film scholars—some educated at NYU or USC, some by VHS—and their movies shared a reverence for what had come before. It wasn’t hard to connect The Matrix’s reality-revealing red pill to Oz’s yellow brick road; or the fax-and-mouse games of The Insider to the hush-hush muckraking of All the President’s Men; or the adrift suburban teens of The Virgin Suicides to the ones in Sixteen Candles.

“We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us,” is the oft spoken mantra of Magnolia, and the past was everywhere you looked in 1999—as if all of those previous cinematic epochs had been compressed, burned onto a zip drive, and passed around from one filmmaker to the next. The movies that loomed largest over 1999 were the ones produced between 1967 and 1979—a period that saw an unparalleled, and today unthinkable, combination of high-IQ thrillers, confrontational comedies, and existentially troubled dramas. For many late-nineties directors, the so-called Easy Riders, Raging Bulls filmmakers—named after Peter Biskind’s myth-making 1998 book—were the big screen’s own greatest generation, executing wild ideas with big-studio backing. “They were movies that dealt with the texture of real life,” says director Alison Maclean, whose 1999 druggie travelogue Jesus’ Son was influenced by such rough-and-tumble seventies pictures as The Long Goodbye and The Panic in Needle Park. “There’s a soulfulness to those films, and a sense of spiritual crisis—of something being broken.”

Decades later, that unvarnished, unfulfilled sense of purpose-driven ennui crept back into movie theaters. Sometimes the links between the movies of 1999 and the films of the Nixon/Carter years were atmospheric: the Gulf War–set Three Kings echoed such combative black comedies as M*A*S*H and Catch-22, while the doomed heartland romance in Boys Don’t Cry recalled the one in Badlands. Other times, the filmmakers had consciously sought to forge connections with the past. Pedro Almodóvar’s Oscar-winning All About My Mother—a vibrant heartbreaker about love and theater—was inspired by John Cassavetes’s 1977 drama Opening Night. Before shooting Magnolia, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson held cast and crew screenings of the 1976 tragicomedy Network for inspiration. And no movie seduced quite as many filmmakers as 1967’s The Graduate, the quintessential tale of rudderless youth that informed everything from Fight Club to Rushmore to American Pie.

But that reverence toward film’s history was matched by a desire to fuck around with its future. Everything was up for grabs in 1999—visually, narratively, thematically. The old “It’s like movie X meets movie Y” descriptors simply didn’t compute anymore. “I remember looking at that lineup in ’99 and thinking, ‘Name me any year between 1967 and 1975 that had more really original young filmmakers tapping into the zeitgeist,’?” says Fight Club’s Edward Norton. “I would stack that year up against any other.” Adds Sam Mendes, whose suburban nightmare debut, American Beauty, earned Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture: “It’s astonishing how many different genres were being redefined. Is The Sixth Sense a horror movie, a thriller, or a ghost story? What is Fight Club? What is Being John Malkovich? Even American Beauty—is it a coming-of-age tale or a fantasy? Something was definitely shifting.”

It wasn’t just genres that were evolving in 1999. Storytelling itself was in the middle of a mutation. Aided by quick-moving digital editing machines and cheap video cameras, filmmakers ripped up and remixed the century-old rules of cinema, screwing with time, perspective, and expectations. Movies such as the madcap Go or Steven Soderbergh’s crisp neo-noir The Limey treated traditional story beats like Tetris blocks, stacking them atop or snugging them around one another—or letting them fall, just to see what form they might take. And The Matrix and The Phantom Menace used immersive digital effects to render entire artificial worlds, which could then be altered with a computer; it was almost as if the filmmakers could actually reach right into the frame and reorder their onscreen universe.

Audience members—who’d spent the nineties retraining their brains to absorb everything from reality TV to Resident Evil to pixel-dusted webcam videos—were willing to play along, even if they didn’t always know what they were getting into. “The entire narrative structure of movies exploded,” notes Lisa Schwarzbaum, an Entertainment Weekly film critic from 1991 to 2013. “You could tell stories in pieces, or backward. You could be lost at the beginning, or you could repeat things, or you could have people flying around the Matrix.”

At times the movies of 1999 felt like part of some mass insurrection, one overseen by three overlapping generations of idiosyncratic filmmakers. “These are very eclectic, interesting directors, who have all stood the test of ‘Do you have anything really to say?’?” notes Fincher, who refers to his peers as “precocious, inspired lunatics.” “Speed was one of the biggest movies that had ever been made at that time—but was [director] Jan de Bont a voice? No. These directors we’re talking about all have something that stains what they do.”

Some of the Class of ’99—including Eyes Wide Shut’s Stanley Kubrick and The Thin Red Line’s Terrence Malick—were returning to moviemaking for the first time in decades. Others, such as Michael Mann (The Insider), had been revered as sly, stylish troublemakers since at least the eighties. Then there were the upstarts who’d begun their careers in the world of lower-budget indies: Wes Anderson (Rushmore), the Wachowskis (The Matrix), and Alexander Payne (Election), among several others. In 1999, they’d all be joined by such nü-brat debutantes as Sofia Coppola, Spike Jonze, and Kimberly Peirce. “We were de facto not the establishment,” Peirce says of her contemporaries. “A bunch of us were reacting to the bigger and more actiony movies of the nineties, saying, ‘That’s not how I think—but I have this story that I really love, one that’s smaller and weirder.’?”

Nearly all the filmmakers of 1999 opted to tell stories that were similarly personal (even if they weren’t always quite so small-scale). And they often subverted the expectations of their own fans. Few would have guessed, for example, that Magnolia’s Paul Thomas Anderson would follow his sweaty porn-biz odyssey Boogie Nights with a sober drama about cancer and interconnectivity. Nor would anyone have predicted that David Lynch—who’d spent the decade making such provocations as Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me—would close out the nineties with a film like The Straight Story, a G-rated, Disney-released tale of an elderly man traveling cross-country on a tractor to visit his ailing brother. If the writers and directors of 1999 shared one unspoken trait, it was the ambition to make something no one had seen before. “Young and older generations came together in this exploratory way,” says Run Lola Run writer-director Tom Tykwer. “There was this beautiful competition between experimental filmmaking and the so-called established filmmaking. But they were also giving each other fire and enthusiasm.”

And they were doing so in a year in which some people were penciling the apocalypse on their calendar, just in case. “There was so much going on about Y2K, and so much talk about computers going haywire, that it even reached down to the people who thought it was total malarkey,” says The Straight Story cowriter and editor Mary Sweeney. “It was the end of a very dramatic decade.”

While the nineties would later be revised by some as a sort of pre-9/11 paradise, the period had in fact been marked by social and political tumult: the beating of Rodney King, the battle over Anita Hill, and terrorist attacks like the bombing in Oklahoma City. By the time 1999 arrived, it felt like anything could happen. “People forget how much anxiety there was,” says Norton. “It was the anxiety of Gen-X entering adulthood, and it had real collateral. It’s expressed in Magnolia, it’s expressed in Fight Club, and it’s expressed in Being John Malkovich: that anxiety about being asked to enter a world that seemed a little bit uninviting.”

But it’s Norton’s Fight Club character—an unnamed solace seeker who dramatically reboots his own life—who discovers the hidden promise of this new era of uncertainty: “Losing all hope was freedom,” he says, and many of the filmmakers and performers from the 1999 movies could relate. Thrown together at the end of the century, and at the height of their industry’s pop-culture powers, they’d been liberated from constraints of budget and technology—and sometimes even the wishes of their bosses—to make whatever movie they wanted, however they wanted. “Maybe it was the rush of everyone thinking about the end of the world,” says Rick Famuyiwa, the writer-director of the 1999 comedy-drama The Wood. “We felt we had to get our voices heard before we all disappeared.”

• • •

And so, as the clocks drew closer to midnight on New Year’s Eve and the Y2K buzzkillers waited it out from their homemade bunkers, the rest of the world prepared to party into a new age. At the White House, President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton hosted a massive gala, as well as a musical concert emceed by Will Smith, he of the recent kinda hit “Will 2K” (“What’s gonna happen/Don’t nobody know/We’ll see when the clock hits twelve-oh-oh”). In Manhattan, nearly a million ball watchers showed up in Times Square—the home of MTV’s studios, where No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani would play R.E.M.’s hyperwordy “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” aided by a grip holding up cue cards.

Meanwhile, at smaller get-togethers across the country, revelers stuck close to friends and family, waiting to make sure the millennium went off without a hitch. Brendan Fraser, star of 1999’s summer hit The Mummy, was in his newly finished home in rainy Los Angeles, watching Tonight Show host Jay Leno fend off the downpour on live television, “looking like a wet cat who was really annoyed,” Fraser says. Shyamalan—no stranger to surprise endings—sat in his Pennsylvania home, keeping an eye on his newborn daughter. Sofia Coppola and her husband, Being John Malkovich director Spike Jonze, gathered for a decadent get-together at her parents’ estate in Napa Valley, California. “If it was the end of the world,” she says, “we were going to do it in style.” And The Matrix’s Joe Pantoliano was at a neighbor’s house in suburban Connecticut, hanging in the laundry room with actor Chazz Palminteri. Pantoliano had stockpiled some valuables for the millennium, just in case. “I’d bought $10,000 worth of silver coins and hid them above the refrigerator,” he says. “If there was any validity to Y2K, I thought I could buy milk and gas and tools.”

Not all of the celebrants that night were quite as concerned about the centennial changeover. Fraser remembers that by December 31, end-times hoopla had gotten so out of hand it was hard to take it seriously: “There’ll be giraffes on fire charging down the street! ATM machines are going to spit cash everywhere!” he jokingly remembers of the warnings.

Yet with an uncertain new decade now closer than ever, it was hard to put such concerns completely out of mind. That night in Los Angeles, Reese Witherspoon, the twenty-three-year-old star of Election and Cruel Intentions, was at a party in Los Angeles, just months after giving birth to her first child. At one point during the festivities, her Cruel Intentions costar (and then husband) Ryan Phillippe took a photo of Witherspoon posing underneath a giant Y2K sign, her hands covering her head. “We were all terrified,” she says.

Meanwhile in Mexico, Marc Gurvitz was heading down a long, darkened road. Fincher, riding with him, noticed the lights had suddenly gone back on at the resort, and asked the gun-toting officials to allow Gurvitz to return to make a phone call. Reluctantly, the driver agreed.

Soon the vehicle was pulling up at the beach—which is where Pitt and the rest of the revelers were waiting. “They’ve all got jeroboams of champagne, and Brad’s wearing this ridiculous gold-sequinned little party hat,” remembers Fincher. The whole thing had been a setup: the power outage, the arrest, even Pitt’s tussling with the federales (“Daniel Day-Lewis would have been awed,” Fincher says of the actor’s performance). After being subjected to Gurvitz’s own practical jokes for days, Fincher and Pitt—the space-monkeys behind Fight Club—had decided to take their revenge, coordinating the stunt with the help of the locals. “It was as harsh as it could be and not be cruel,” says Fincher, still chuckling at the ruse decades later. “Listen, if we could have had gunfire with blanks, we’d have done it, but it was a last-minute thing.” Even Gurvitz eventually laughed, “after I cleaned up my pants,” he says. “It was like Fincher choreographed a movie. That’s how sick these fucking guys are.”

As midnight arrived across the world, millions felt the same way as Gurvitz: They’d been pranked. The meltdown of Y2K never arrived. Computers kept humming; planes remained airborne; bank accounts survived. “Just a whimper, not a bang,” says Fraser.

Y2K was its own kind of phantom menace. We’d spent so much time wondering what the twenty-first century might look like, most of us failed to notice that it had already shown up. And if you wanted to see it, all you had to do was go to the movies.

Recenzii

“Best. Movie. Year. Ever. is a terrifically fun snapshot of American film culture on the brink of the Millennium. Brian Raftery is the ultimate pop-culture savant. From indies to blockbusters, auteurs to amateurs, he covers it all, as both a keen-eyed journalist and a true movie fan, delivering inside information and no small amount of laughs. I loved this book—even though it made me want to call in sick for a week, and go back and watch (or re-watch) the movies from this great year in film. An absolute must for any movie-lover or pop-culture nut!” —Gillian Flynn

"Two decades on, modern filmmakers still reference, study and worship the incredible films of 1999. Brian Raftery more than gives this era its due in this tremendously well-researched and insightful book." —Diablo Cody, Academy Award-winning screenwriter of Juno, Young Adult and Tully

"Even while it was happening, 1999 felt like an unusually interesting year for film. But what Brian Raftery illustrates in this deeply researched book is that classifying 1999 as interesting doesn't go far enough. It was a hinge moment for cinematic entertainment that still reverberates today, in ways I had either forgotten or never knew originally. This is the complete portrait of what it was like to spend a year inside a movie theater at the best possible moment in time." —Chuck Klosterman

"Brian Raftery expertly wields a journalist’s exhaustiveness and a novelist’s prose in Best. Movie. Year. Ever. His exclusive reporting and inside-out examination of 1999’s groundbreaking movies explain why the year remains the best movie year recorded and one who’s impact and reach will be felt in cinema for years to come." —Jonathan Abrams, New York Times bestselling author of All the Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of The Wire

"Best. Movie. Year. Ever. is packed with behind-the-scenes anecdotes from creators, as well as Raftery’s sharp, fair-minded and witty analysis—the culmination of over 30 years of an unwavering love for the big screen."—Mary Kaye Schilling, Newsweek

"The amount of research and reporting Raftery has done is as staggering as the year’s list of films. Best.Movie.Year.Ever is a fun and illuminating read and a highly recommended non-fiction title, not only for movie fans but also for lovers of mystery, crime and thriller films."

Mystery Tribune

"Two decades on, modern filmmakers still reference, study and worship the incredible films of 1999. Brian Raftery more than gives this era its due in this tremendously well-researched and insightful book." —Diablo Cody, Academy Award-winning screenwriter of Juno, Young Adult and Tully

"Even while it was happening, 1999 felt like an unusually interesting year for film. But what Brian Raftery illustrates in this deeply researched book is that classifying 1999 as interesting doesn't go far enough. It was a hinge moment for cinematic entertainment that still reverberates today, in ways I had either forgotten or never knew originally. This is the complete portrait of what it was like to spend a year inside a movie theater at the best possible moment in time." —Chuck Klosterman

"Brian Raftery expertly wields a journalist’s exhaustiveness and a novelist’s prose in Best. Movie. Year. Ever. His exclusive reporting and inside-out examination of 1999’s groundbreaking movies explain why the year remains the best movie year recorded and one who’s impact and reach will be felt in cinema for years to come." —Jonathan Abrams, New York Times bestselling author of All the Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of The Wire

"Best. Movie. Year. Ever. is packed with behind-the-scenes anecdotes from creators, as well as Raftery’s sharp, fair-minded and witty analysis—the culmination of over 30 years of an unwavering love for the big screen."—Mary Kaye Schilling, Newsweek

"The amount of research and reporting Raftery has done is as staggering as the year’s list of films. Best.Movie.Year.Ever is a fun and illuminating read and a highly recommended non-fiction title, not only for movie fans but also for lovers of mystery, crime and thriller films."

Mystery Tribune

Descriere

From a veteran culture writer, a celebration and analysis of the movies of 1999 — arguably the most groundbreaking year in cinematic history.