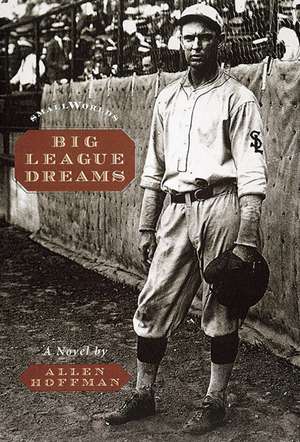

Big League Dreams: Small Worlds

Autor Allen Hoffmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 1999

In St. Louis, it is the summer of 1920 and the day is the Sabbath, but there is little rest for the Jews from Krimsk and less reverence for the wondrous Krimsker Rebbe, who led them to the New World seventeen years before. The rebbe's former hasidim have embraced America to discover that the vision of "gold in the streets" evokes larceny in the heart. Matti Sternweiss, the ungainly, studious child wonder in Krimsk, now the cerebral catcher for the St. Louis Browns, is scheming to fix Saturday's game against the pennant-contending Detroit Tigers.

It is an American Sabbath: Prohibition, bookies, the criminal syndicate, the Hiberian fellowship of the police brass, hometown blondes, a bootlegging rabbi, and big league baseball. It is also Krimsk in America: Boruch Levi, the successful junkman, confiscates his zany, crippled brother-in-law Barasch's sizable bets; Barasch's lusty wife, Malka, has her own connubial reasons for wanting to stop the gambling; the chief of police fatefully inspires his loyal disciple, Boruch Levi, to bring Matti before the Krimsker Rebbe on the Sabbath in order to preserve the purity of the national pastime.

Recluse and wonder-worker, messianist and pragmatist, the Krimsker Rebbe navigates the muddy Mississippi River, haunted by a recurring prophetic vision of Pharaoh's blood-red Nile. In the final, decisive innings, with Matti crouched behind home plate, it will come down to Ty Cobb versus the kabbalah.

Richly imagined, populated with robust, complex characters, Big League Dreams is a profoundly original, inspiring, and comic creation. It is the second volume in the series Small Worlds, which follows the people of Krimsk and their descendants in America, Russia, Poland, and Israel. In each volume Allen Hoffman draws on his deep knowledge of Jewish religion and history to evoke the finite yet infinite "small worlds" his characters inhabit.

It is an American Sabbath: Prohibition, bookies, the criminal syndicate, the Hiberian fellowship of the police brass, hometown blondes, a bootlegging rabbi, and big league baseball. It is also Krimsk in America: Boruch Levi, the successful junkman, confiscates his zany, crippled brother-in-law Barasch's sizable bets; Barasch's lusty wife, Malka, has her own connubial reasons for wanting to stop the gambling; the chief of police fatefully inspires his loyal disciple, Boruch Levi, to bring Matti before the Krimsker Rebbe on the Sabbath in order to preserve the purity of the national pastime.

Recluse and wonder-worker, messianist and pragmatist, the Krimsker Rebbe navigates the muddy Mississippi River, haunted by a recurring prophetic vision of Pharaoh's blood-red Nile. In the final, decisive innings, with Matti crouched behind home plate, it will come down to Ty Cobb versus the kabbalah.

Richly imagined, populated with robust, complex characters, Big League Dreams is a profoundly original, inspiring, and comic creation. It is the second volume in the series Small Worlds, which follows the people of Krimsk and their descendants in America, Russia, Poland, and Israel. In each volume Allen Hoffman draws on his deep knowledge of Jewish religion and history to evoke the finite yet infinite "small worlds" his characters inhabit.

Preț: 55.00 lei

Preț vechi: 631.73 lei

-91% Nou

Puncte Express: 83

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.53€ • 10.95$ • 8.69£

10.53€ • 10.95$ • 8.69£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789205834

ISBN-10: 0789205831

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 122 x 193 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Small Worlds

ISBN-10: 0789205831

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 122 x 193 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Small Worlds

Cuprins

Contents

Recollections

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

The Letter

About the Author

Recollections

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

The Letter

About the Author

Notă biografică

Allen Hoffman, award-winning author of the novel Small Worlds and of a novella and short stories, was born in St. Louis and received his B.A. in American history from Harvard University. He studied the Talmud in yeshivas in New York and Jerusalem, and has taught in New York City schools. He and his wife and four children live in Jerusalem. He teaches English literature and creative writing at Bar-Ilan University.

Extras

Chapter One

The white-bearded old man opened the Fords back door and with surprising ease hoisted a large trunk into the automobile. Remarkably erect and robust for his seventy years, he was not even sweating in the warm morning sunlight. As a concession to the St. Louis climate and this mornings physical task, he had removed his suit jacket but not his hat. He would like to have taken that off, too, but he was slightly embarrassed to appear on a public street in a skullcap. The tree-shaded suburban neighborhood knew him as the Krimsker Rebbes sexton, and it wouldnt have mattered to the Germans, Irish, and Italians, who inhabited the numerous duplexes and occasional apartment house and were really very fine neighbors, friendly, polite, and respectful. It mattered to Reb Zelig, however, because this was America, and whenever he could avoid calling attention to the difference, he preferred to do so. He had shortened his side curls and had tucked them behind his ears; he wore a modern short suit jacket and broad-brimmed felt hat. Outside the neighborhood they often mistook him for an old-fashioned farmer. That is, when he was alone. The Krimsker Rebbe himself wasnt embarrassed to go anywhere in a skullcap--he didnt tuck his long side curls behind any ear either--and his long frock coat trailed ostentatiously behind him like a Civil War relic.

When they had suddenly left Krimsk in 1903, Reb Zelig never had expected to understand the Krimsker Rebbe, and the rebbe did not disappoint him. But Reb Zelig had been puzzled more than usual recently when the rebbe insisted that he, Reb Zelig, must say the mourners kaddish for the deposed and executed Tsar Nicholas II. Reb Zelig mentioned to the rebbe that they were no longer in Russia, and Nicholas had been deposed before his death. The rebbe flicked his wrist impatiently and said, "Nu, you can ask a better question. Ask why a goy like you should say kaddish for a Jew. Ask me, and Ill tell you the answer. You killed him, and theres no one else to say kaddish for him, so you might as well do it."

In Krimsk, Reb Zelig would have assumed that the rebbe was referring to great kabbalistic secrets and mysteries. But such esoteric lore, essential as it was in the Russian village of Krimsk, seemed so very alien in St. Louis. Reb Zelig even wondered if the rebbe knew what he was talking about. Still, Reb Zelig had dutifully begun to say the memorial prayer, informing inquisitive congregants that the rebbe had told him to do so for the victims of the Bolshevik Revolution, who had no one left to say it in their memory, a story that was petty much true as far as it went. Occasionally Reb Zelig wondered what the rebbe had really meant, but even in America he wasnt about to take that much liberty with his rebbe as to ask him directly.

Most of the time the rebbe seemed aware of his surroundings--even when he went around the Osage Indian reservation with his phylacteries on his head and arm as if he were in the beis midrash back in Krimsk. Once Reb Zelig had asked the rebbe why he found the Indians so fascinating.

"Here," the rebbe said, pointing to the Osage encampment, "and only here lies the secret to America. Here and nowhere else." It all seemed a little strange to Reb Zelig, but he was only a sexton, not given to unraveling great secrets. Not given to killing people either, much less former tsars. Some day maybe the rebbe would explain that to him, too.

But tomorrow morning it would be the Osage Indians who were perplexed; tomorrow would be the Sabbath, and no Jew wore his phylacteries on the Sabbath. The Indians had never seen the rebbe on a Sabbath. In fact, Reb Zelig himself was slightly perplexed that they were about to drive down to the reservation. The rebbe had always insisted on returning home to St. Louis for the Sabbath, no matter how far or how fast Reb Zelig had to drive. Perhaps there was a very special ceremony that the rebbe wanted to observe. Reb Zelig would find out soon enough, but now that he had the automobile loaded, he had better put on his jacket and tell the rebbe that they could get started. They had a long journey and wanted to arrive well before sunset, when the Sabbath would begin.

The white-bearded old man opened the Fords back door and with surprising ease hoisted a large trunk into the automobile. Remarkably erect and robust for his seventy years, he was not even sweating in the warm morning sunlight. As a concession to the St. Louis climate and this mornings physical task, he had removed his suit jacket but not his hat. He would like to have taken that off, too, but he was slightly embarrassed to appear on a public street in a skullcap. The tree-shaded suburban neighborhood knew him as the Krimsker Rebbes sexton, and it wouldnt have mattered to the Germans, Irish, and Italians, who inhabited the numerous duplexes and occasional apartment house and were really very fine neighbors, friendly, polite, and respectful. It mattered to Reb Zelig, however, because this was America, and whenever he could avoid calling attention to the difference, he preferred to do so. He had shortened his side curls and had tucked them behind his ears; he wore a modern short suit jacket and broad-brimmed felt hat. Outside the neighborhood they often mistook him for an old-fashioned farmer. That is, when he was alone. The Krimsker Rebbe himself wasnt embarrassed to go anywhere in a skullcap--he didnt tuck his long side curls behind any ear either--and his long frock coat trailed ostentatiously behind him like a Civil War relic.

When they had suddenly left Krimsk in 1903, Reb Zelig never had expected to understand the Krimsker Rebbe, and the rebbe did not disappoint him. But Reb Zelig had been puzzled more than usual recently when the rebbe insisted that he, Reb Zelig, must say the mourners kaddish for the deposed and executed Tsar Nicholas II. Reb Zelig mentioned to the rebbe that they were no longer in Russia, and Nicholas had been deposed before his death. The rebbe flicked his wrist impatiently and said, "Nu, you can ask a better question. Ask why a goy like you should say kaddish for a Jew. Ask me, and Ill tell you the answer. You killed him, and theres no one else to say kaddish for him, so you might as well do it."

In Krimsk, Reb Zelig would have assumed that the rebbe was referring to great kabbalistic secrets and mysteries. But such esoteric lore, essential as it was in the Russian village of Krimsk, seemed so very alien in St. Louis. Reb Zelig even wondered if the rebbe knew what he was talking about. Still, Reb Zelig had dutifully begun to say the memorial prayer, informing inquisitive congregants that the rebbe had told him to do so for the victims of the Bolshevik Revolution, who had no one left to say it in their memory, a story that was petty much true as far as it went. Occasionally Reb Zelig wondered what the rebbe had really meant, but even in America he wasnt about to take that much liberty with his rebbe as to ask him directly.

Most of the time the rebbe seemed aware of his surroundings--even when he went around the Osage Indian reservation with his phylacteries on his head and arm as if he were in the beis midrash back in Krimsk. Once Reb Zelig had asked the rebbe why he found the Indians so fascinating.

"Here," the rebbe said, pointing to the Osage encampment, "and only here lies the secret to America. Here and nowhere else." It all seemed a little strange to Reb Zelig, but he was only a sexton, not given to unraveling great secrets. Not given to killing people either, much less former tsars. Some day maybe the rebbe would explain that to him, too.

But tomorrow morning it would be the Osage Indians who were perplexed; tomorrow would be the Sabbath, and no Jew wore his phylacteries on the Sabbath. The Indians had never seen the rebbe on a Sabbath. In fact, Reb Zelig himself was slightly perplexed that they were about to drive down to the reservation. The rebbe had always insisted on returning home to St. Louis for the Sabbath, no matter how far or how fast Reb Zelig had to drive. Perhaps there was a very special ceremony that the rebbe wanted to observe. Reb Zelig would find out soon enough, but now that he had the automobile loaded, he had better put on his jacket and tell the rebbe that they could get started. They had a long journey and wanted to arrive well before sunset, when the Sabbath would begin.