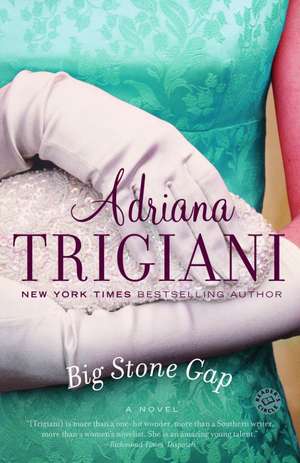

Big Stone Gap: Big Stone Gap Novels

Autor Adriana Trigianien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2001

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 57.67 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.04 lei 6-12 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 14 apr 2021 | 57.67 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.04 lei 6-12 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 6 mai 2002 | 57.80 lei 3-5 săpt. | +10.54 lei 6-12 zile |

Preț: 93.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 141

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.98€ • 18.69$ • 14.91£

17.98€ • 18.69$ • 14.91£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345438324

ISBN-10: 0345438329

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Big Stone Gap Novels

ISBN-10: 0345438329

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Big Stone Gap Novels

Notă biografică

Adriana Trigiani is beloved by millions of readers around the world for her fifteen bestsellers, including the blockbuster epic The Shoemaker’s Wife; the Big Stone Gap series; Lucia, Lucia; the Valentine series; the Viola series for young adults; and the bestselling memoir Don’t Sing at the Table. Trigiani reaches new heights with All the Stars in the Heavens, an epic tale from the Golden Age of Hollywood. She is the award-winning filmmaker of the documentary Queens of the Big Time. Trigiani wrote and directed the major motion picture Big Stone Gap, based on her debut novel and filmed entirely on location in her Virginia hometown. She lives in Greenwich Village with her family.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

This will be a good weekend for reading. I picked up a dozen of Vernie Crabtree’s killer chocolate chip cookies at the French Club bake sale yesterday. (I don’t know what she puts in them, but they’re chewy and crispy at the same time.) Those, a pot of coffee, and a good book are all I will need for the rainy weekend rolling in. It’s early September in our mountains, so it’s warm during the day, but tonight will bring a cool mist to remind us that fall is right around the corner.

The Wise County Bookmobile is one of the most beautiful sights in the world to me. When I see it lumbering down the mountain road like a tank, then turning wide and easing onto Shawnee Avenue, I flag it down like an old friend. I’ve waited on this corner every Friday since I can remember. The Bookmobile is just a government truck, but to me it’s a glittering royal coach delivering stories and knowledge and life itself. I even love the smell of books. People have often told me that one of their strongest childhood memories is the scent of their grandmother’s house. I never knew my grandmothers, but I could always count on the Bookmobile.

The most important thing I ever learned, I learned from books. Books have taught me how to size people up. The most useful book I ever read taught me how to read faces, an ancient Chinese art called siang mien, in which the size of the eyes, curve of the lip, and height of the forehead are important clues to a person’s character. The placement of ears indicates intelligence. Chins that stick out reflect stubbornness. Deep-set eyes suggest a secretive nature. Eyebrows that grow together may answer the question Could that man kill me with his bare hands? (He could.) Even dimples have meaning. I have them, and according to face-reading, something wonderful is supposed to happen to me when I turn thirty-five. (It’s been four months since my birthday, and I’m still waiting.)

If you were to read my face, you would find me a comfortable person with brown eyes, good teeth, nice lips, and a nose that folks, when they are being kind, refer to as noble. It’s a large nose, but at least it’s straight. My eyebrows are thick, which indicates a practical nature. (I’m a pharmacist—how much more practical can you get?) I have a womanly shape, known around here as a mountain girl’s body, strong legs, and a flat behind. Jackets cover it quite nicely.

This morning the idea of living in Big Stone Gap for the rest of my life gives me a nervous feeling. I stop breathing, as I do whenever I think too hard. Not breathing is very bad for you, so I inhale slowly and deeply. I taste coal dust. I don’t mind; it assures me that we still have an economy. Our town was supposed to become the “Pittsburgh of the South” and the “Coal Mining Capital of Virginia.” That never happened, so we are forever at the whims of the big coal companies. When they tell us the coal is running out in these mountains, who are we to doubt them?

It’s pretty here. Around six o’clock at night everything turns a rich Crayola midnight blue. You will never smell greenery so pungent. The Gap definitely has its romantic qualities. Even the train whistles are musical, sweet oboes in the dark. The place can fill you with longing.

The Bookmobile is at the stoplight. The librarian and driver is a good-time gal named Iva Lou Wade. She’s in her forties, but she’s yet to place the flag on her sexual peak. She’s got being a woman down. If you painted her, she’d be sitting on a pink cloud with gold-leaf edges, showing a lot of leg. Her perfume is so loud that when I visit the Bookmobile, I wind up smelling like her for the bulk of the day. (It’s a good thing I like Coty’s Emeraude.) My father used to say that that’s how a woman ought to be. “A man should know when there’s a woman in the room. When Iva Lou comes in, there ain’t no doubt.” I’d just say nothing and roll my eyes.

Iva Lou’s having a tough time parking. A mail truck has parked funny in front of the post office, taking up her usual spot, so she motions to me that she’s pulling into the gas station. That’s fine with the owner, Kent Vanhook. He likes Iva Lou a lot. What man doesn’t? She pays real nice attention to each and every one. She examines men like eggs, perfect specimens created by God to nourish. And she hasn’t met a man yet who doesn’t appreciate it. Luring a man is a true talent, like playing the piano by ear. Not all of us are born prodigies, but women like Iva Lou have made it an art form.

The Bookmobile doors open with a whoosh. I can’t believe what Iva Lou’s wearing: Her ice-blue turtleneck is so tight it looks like she’s wearing her bra on the outside. Her Mondrian-patterned pants, with squares of pale blue, yellow, and green, cling to her thighs like crisscross ribbons. Even sitting, Iva Lou has an unbelievable shape. But I wonder how much of it has to do with all the cinching. Could it be that her parts are so well-hoisted and suspended, she has transformed her real figure into a soft hourglass? Her face is childlike, with a small chin, big blue eyes, and a rosebud mouth. Her eyeteeth snaggle out over her front teeth, but on her they’re demure. Her blond hair is like yellow Easter straw, arranged in an upsweep you can see through the set curls. She wears lots of Sarah Coventry jewelry, because she sells it on the side.

“I’ll trade you. Shampoo for a best-seller.” I give Iva Lou a sack of shampoo samples from my pharmacy, Mulligan’s Mutual.

“You got a deal.” Iva Lou grabs the sack and starts sorting through the samples. She indicates the shelf of new arrivals. “Ave Maria, honey, you have got to read The Captains and the Kings that just came out. I know you don’t like historicals, but this one’s got sex.”

“How much more romance can you handle, Iva Lou? You’ve got half the men in Big Stone Gap tied up in knots.”

She snickers. “Half? Oh well, I’m-a gonna take that as a compliment-o anyway.” I’m half Italian, so Iva Lou insists on ending her words with vowels. I taught her some key phrases in Italian in case international romance was to present itself. It wasn’t very funny when Iva Lou tried them out on my mother one day. I sure got in some Big Trouble over that.

Iva Lou has a goal. She wants to make love to an Italian man, so she can decide if they are indeed the world’s greatest lovers. “Eye-talian men are my Matta-horn, honey,” she declares. Too bad there aren’t any in these parts. The people around here are mainly Scotch-Irish, or Melungeon (folks who are a mix of Turkish, French, African, Indian, and who knows what; they live up in the mountain hollers and stick to themselves). Zackie Wakin, owner of the town department store, is Lebanese. My mother and I were the only Italians; and then about five years ago we acquired one Jew, Lewis Eisenberg, a lawyer from Woodbury, New York.

“You always sit in the third snap stool. How come?” Iva Lou asks, not looking up as she flips through a new coffee-table book about travel photography.

“I like threes.”

“Sweetie-o, let me tell you something.” Iva Lou gets a faraway, mystical twinkle in her eye. Then her voice lowers to a throaty, sexy register. “When I get to blow this coal yard, and have my big adventure, I sure as hell won’t waste my time taking pictures of the Circus Maximus. I am not interested in rocks ’n’ ruins. I want to experience me some flesh and blood. Some magnificent, broad-shouldered hunk of a European man. Forget the points of interest, point me toward the men. Marble don’t hug back, baby.” Then she breathes deeply, “Whoo.”

Iva Lou fixes herself a cup of Sanka and laughs. She’s one of those people who are forever cracking themselves up. She always offers me a cup, and I always decline. I know that her one spare clean Styrofoam cup could be her entrée to a romantic rendezvous. Why waste it on me?

“I found you that book on wills you wanted. And here’s the only one I could find on grief.” Iva Lou holds up As Grief Exits as though she’s modeling it. The pretty cover has rococo cherubs and clouds on it. The angels’ smiles are instantly comforting. “How you been getting along?” I look at Iva Lou’s face. Her innocent expression is just like the cherubs’. She really wants to know how I am.

My mother died on August 2, 1978, exactly one month ago today. It was the worst day of my life. She had breast cancer. I never thought cancer would get both of my parents, but it did. Mama was fifty-two years old, which suddenly seems awfully young to me. She was only seventeen when she came to America. My father taught her English, but she always spoke with a thick accent. One of the things I miss most about her is the sound of her voice. Sometimes when I close my eyes I can hear her.

Mama didn’t want to die because she didn’t want to leave me here alone. I have no brothers or sisters. The roots in the Mulligan family are strong, but at this point, the branches are mostly dead. My mother never spoke of her family over in Italy, so I assume they died in the war or something. The only relative I have left is my aunt, Alice Mulligan Lambert. She is a pill. Her husband, my Uncle Wayne, has spent his life trying not to make her angry, but he has failed. Aunt Alice has a small head and thin lips. (That’s a terrible combination.)

“I’m gonna take a smoke, honey-o.” Iva Lou climbs down the steps juggling two coffees and her smokes. In under fifteen seconds, Kent Vanhook comes out from the garage, wiping his hands on a rag. Iva Lou gives Kent the Styrofoam cup, which looks tiny in his big hands. They smoke and sip. Kent Vanhook is a good-looking man of fifty, a tall, easygoing cowboy type. He looks like the great Walter Pidgeon with less hair. As he laughs with Iva Lou, twenty years seem to melt off of his face. Kent’s wife is a diabetic who stays at home and complains a lot. I know this because I drop off her insulin once a month. But with Iva Lou, all Kent does is laugh.

I like to be alone on the Bookmobile. It gives me a chance to really examine the new arrivals. I make a stack and then look through the old selections. I pick up my old standby, The Ancient Art of Chinese Face-Reading, and think of my father, Fred Mulligan. When he died thirteen years ago, I thought I would grieve, but to this day I haven’t. We weren’t close, but it wasn’t from my lack of trying. From the time I can remember, he just looked through me, the way you would look through the thick glass of a jelly jar to see if there’s any jelly left. Many nights when I was young I cried about him, and then one day I stopped expecting him to love me and the pain went away. I stuck by him when he got sick, though. All of a sudden, my father, who had always separated himself from people, had everything in common with the world. He was in pain and would inevitably die. The suffering gave him some humility. It’s sad that my best memories of him are when he was sick. It was then that I first checked out this book on Chinese face-reading.

I thought that if I read my father’s face, I would be able to understand why he was so mean. It took a lot of study. Dad’s face was square and full of angles: rectangular forehead, sharp jaw, pointy chin. He had small eyes (sign of a deceptive nature), a bulbous nose (sign of money in midlife, which he had from owning the Pharmacy), and no lips. Okay, he had two lips, but the set of the mouth was one tight gray lead-pencil line. That is a sign of cruelty. When you watch the news on television, look at the anchor’s mouth. I will guaran-damn-tee you that none of them have upper lips. You don’t get on the TV by being nice to people.

On and off for about four years straight the face-reading book was checked out in my name, and my name only. When I went up to Charlottesville on a buying trip for the Pharmacy, I tried to hunt down a copy to buy. It was out of print. Iva Lou has tried to give me the book outright many times. She said she would report it as lost. But I can’t do that. I like knowing it’s here, riding around with old Iva Lou.

I guess I’m staring out the windshield at them, because they’re both looking at me. Iva Lou stomps out her cigarette with her pink Papagallo flat and heads back toward the Bookmobile. Kent watches her return, drinking her in like that last sip of rich, black Sanka.

“I’m sorry. Me and Kent got to talking and, well, you know.”

“No problem.”

“Face-reading again? Don’t you have this memorized by now? Lordy.”

This will be a good weekend for reading. I picked up a dozen of Vernie Crabtree’s killer chocolate chip cookies at the French Club bake sale yesterday. (I don’t know what she puts in them, but they’re chewy and crispy at the same time.) Those, a pot of coffee, and a good book are all I will need for the rainy weekend rolling in. It’s early September in our mountains, so it’s warm during the day, but tonight will bring a cool mist to remind us that fall is right around the corner.

The Wise County Bookmobile is one of the most beautiful sights in the world to me. When I see it lumbering down the mountain road like a tank, then turning wide and easing onto Shawnee Avenue, I flag it down like an old friend. I’ve waited on this corner every Friday since I can remember. The Bookmobile is just a government truck, but to me it’s a glittering royal coach delivering stories and knowledge and life itself. I even love the smell of books. People have often told me that one of their strongest childhood memories is the scent of their grandmother’s house. I never knew my grandmothers, but I could always count on the Bookmobile.

The most important thing I ever learned, I learned from books. Books have taught me how to size people up. The most useful book I ever read taught me how to read faces, an ancient Chinese art called siang mien, in which the size of the eyes, curve of the lip, and height of the forehead are important clues to a person’s character. The placement of ears indicates intelligence. Chins that stick out reflect stubbornness. Deep-set eyes suggest a secretive nature. Eyebrows that grow together may answer the question Could that man kill me with his bare hands? (He could.) Even dimples have meaning. I have them, and according to face-reading, something wonderful is supposed to happen to me when I turn thirty-five. (It’s been four months since my birthday, and I’m still waiting.)

If you were to read my face, you would find me a comfortable person with brown eyes, good teeth, nice lips, and a nose that folks, when they are being kind, refer to as noble. It’s a large nose, but at least it’s straight. My eyebrows are thick, which indicates a practical nature. (I’m a pharmacist—how much more practical can you get?) I have a womanly shape, known around here as a mountain girl’s body, strong legs, and a flat behind. Jackets cover it quite nicely.

This morning the idea of living in Big Stone Gap for the rest of my life gives me a nervous feeling. I stop breathing, as I do whenever I think too hard. Not breathing is very bad for you, so I inhale slowly and deeply. I taste coal dust. I don’t mind; it assures me that we still have an economy. Our town was supposed to become the “Pittsburgh of the South” and the “Coal Mining Capital of Virginia.” That never happened, so we are forever at the whims of the big coal companies. When they tell us the coal is running out in these mountains, who are we to doubt them?

It’s pretty here. Around six o’clock at night everything turns a rich Crayola midnight blue. You will never smell greenery so pungent. The Gap definitely has its romantic qualities. Even the train whistles are musical, sweet oboes in the dark. The place can fill you with longing.

The Bookmobile is at the stoplight. The librarian and driver is a good-time gal named Iva Lou Wade. She’s in her forties, but she’s yet to place the flag on her sexual peak. She’s got being a woman down. If you painted her, she’d be sitting on a pink cloud with gold-leaf edges, showing a lot of leg. Her perfume is so loud that when I visit the Bookmobile, I wind up smelling like her for the bulk of the day. (It’s a good thing I like Coty’s Emeraude.) My father used to say that that’s how a woman ought to be. “A man should know when there’s a woman in the room. When Iva Lou comes in, there ain’t no doubt.” I’d just say nothing and roll my eyes.

Iva Lou’s having a tough time parking. A mail truck has parked funny in front of the post office, taking up her usual spot, so she motions to me that she’s pulling into the gas station. That’s fine with the owner, Kent Vanhook. He likes Iva Lou a lot. What man doesn’t? She pays real nice attention to each and every one. She examines men like eggs, perfect specimens created by God to nourish. And she hasn’t met a man yet who doesn’t appreciate it. Luring a man is a true talent, like playing the piano by ear. Not all of us are born prodigies, but women like Iva Lou have made it an art form.

The Bookmobile doors open with a whoosh. I can’t believe what Iva Lou’s wearing: Her ice-blue turtleneck is so tight it looks like she’s wearing her bra on the outside. Her Mondrian-patterned pants, with squares of pale blue, yellow, and green, cling to her thighs like crisscross ribbons. Even sitting, Iva Lou has an unbelievable shape. But I wonder how much of it has to do with all the cinching. Could it be that her parts are so well-hoisted and suspended, she has transformed her real figure into a soft hourglass? Her face is childlike, with a small chin, big blue eyes, and a rosebud mouth. Her eyeteeth snaggle out over her front teeth, but on her they’re demure. Her blond hair is like yellow Easter straw, arranged in an upsweep you can see through the set curls. She wears lots of Sarah Coventry jewelry, because she sells it on the side.

“I’ll trade you. Shampoo for a best-seller.” I give Iva Lou a sack of shampoo samples from my pharmacy, Mulligan’s Mutual.

“You got a deal.” Iva Lou grabs the sack and starts sorting through the samples. She indicates the shelf of new arrivals. “Ave Maria, honey, you have got to read The Captains and the Kings that just came out. I know you don’t like historicals, but this one’s got sex.”

“How much more romance can you handle, Iva Lou? You’ve got half the men in Big Stone Gap tied up in knots.”

She snickers. “Half? Oh well, I’m-a gonna take that as a compliment-o anyway.” I’m half Italian, so Iva Lou insists on ending her words with vowels. I taught her some key phrases in Italian in case international romance was to present itself. It wasn’t very funny when Iva Lou tried them out on my mother one day. I sure got in some Big Trouble over that.

Iva Lou has a goal. She wants to make love to an Italian man, so she can decide if they are indeed the world’s greatest lovers. “Eye-talian men are my Matta-horn, honey,” she declares. Too bad there aren’t any in these parts. The people around here are mainly Scotch-Irish, or Melungeon (folks who are a mix of Turkish, French, African, Indian, and who knows what; they live up in the mountain hollers and stick to themselves). Zackie Wakin, owner of the town department store, is Lebanese. My mother and I were the only Italians; and then about five years ago we acquired one Jew, Lewis Eisenberg, a lawyer from Woodbury, New York.

“You always sit in the third snap stool. How come?” Iva Lou asks, not looking up as she flips through a new coffee-table book about travel photography.

“I like threes.”

“Sweetie-o, let me tell you something.” Iva Lou gets a faraway, mystical twinkle in her eye. Then her voice lowers to a throaty, sexy register. “When I get to blow this coal yard, and have my big adventure, I sure as hell won’t waste my time taking pictures of the Circus Maximus. I am not interested in rocks ’n’ ruins. I want to experience me some flesh and blood. Some magnificent, broad-shouldered hunk of a European man. Forget the points of interest, point me toward the men. Marble don’t hug back, baby.” Then she breathes deeply, “Whoo.”

Iva Lou fixes herself a cup of Sanka and laughs. She’s one of those people who are forever cracking themselves up. She always offers me a cup, and I always decline. I know that her one spare clean Styrofoam cup could be her entrée to a romantic rendezvous. Why waste it on me?

“I found you that book on wills you wanted. And here’s the only one I could find on grief.” Iva Lou holds up As Grief Exits as though she’s modeling it. The pretty cover has rococo cherubs and clouds on it. The angels’ smiles are instantly comforting. “How you been getting along?” I look at Iva Lou’s face. Her innocent expression is just like the cherubs’. She really wants to know how I am.

My mother died on August 2, 1978, exactly one month ago today. It was the worst day of my life. She had breast cancer. I never thought cancer would get both of my parents, but it did. Mama was fifty-two years old, which suddenly seems awfully young to me. She was only seventeen when she came to America. My father taught her English, but she always spoke with a thick accent. One of the things I miss most about her is the sound of her voice. Sometimes when I close my eyes I can hear her.

Mama didn’t want to die because she didn’t want to leave me here alone. I have no brothers or sisters. The roots in the Mulligan family are strong, but at this point, the branches are mostly dead. My mother never spoke of her family over in Italy, so I assume they died in the war or something. The only relative I have left is my aunt, Alice Mulligan Lambert. She is a pill. Her husband, my Uncle Wayne, has spent his life trying not to make her angry, but he has failed. Aunt Alice has a small head and thin lips. (That’s a terrible combination.)

“I’m gonna take a smoke, honey-o.” Iva Lou climbs down the steps juggling two coffees and her smokes. In under fifteen seconds, Kent Vanhook comes out from the garage, wiping his hands on a rag. Iva Lou gives Kent the Styrofoam cup, which looks tiny in his big hands. They smoke and sip. Kent Vanhook is a good-looking man of fifty, a tall, easygoing cowboy type. He looks like the great Walter Pidgeon with less hair. As he laughs with Iva Lou, twenty years seem to melt off of his face. Kent’s wife is a diabetic who stays at home and complains a lot. I know this because I drop off her insulin once a month. But with Iva Lou, all Kent does is laugh.

I like to be alone on the Bookmobile. It gives me a chance to really examine the new arrivals. I make a stack and then look through the old selections. I pick up my old standby, The Ancient Art of Chinese Face-Reading, and think of my father, Fred Mulligan. When he died thirteen years ago, I thought I would grieve, but to this day I haven’t. We weren’t close, but it wasn’t from my lack of trying. From the time I can remember, he just looked through me, the way you would look through the thick glass of a jelly jar to see if there’s any jelly left. Many nights when I was young I cried about him, and then one day I stopped expecting him to love me and the pain went away. I stuck by him when he got sick, though. All of a sudden, my father, who had always separated himself from people, had everything in common with the world. He was in pain and would inevitably die. The suffering gave him some humility. It’s sad that my best memories of him are when he was sick. It was then that I first checked out this book on Chinese face-reading.

I thought that if I read my father’s face, I would be able to understand why he was so mean. It took a lot of study. Dad’s face was square and full of angles: rectangular forehead, sharp jaw, pointy chin. He had small eyes (sign of a deceptive nature), a bulbous nose (sign of money in midlife, which he had from owning the Pharmacy), and no lips. Okay, he had two lips, but the set of the mouth was one tight gray lead-pencil line. That is a sign of cruelty. When you watch the news on television, look at the anchor’s mouth. I will guaran-damn-tee you that none of them have upper lips. You don’t get on the TV by being nice to people.

On and off for about four years straight the face-reading book was checked out in my name, and my name only. When I went up to Charlottesville on a buying trip for the Pharmacy, I tried to hunt down a copy to buy. It was out of print. Iva Lou has tried to give me the book outright many times. She said she would report it as lost. But I can’t do that. I like knowing it’s here, riding around with old Iva Lou.

I guess I’m staring out the windshield at them, because they’re both looking at me. Iva Lou stomps out her cigarette with her pink Papagallo flat and heads back toward the Bookmobile. Kent watches her return, drinking her in like that last sip of rich, black Sanka.

“I’m sorry. Me and Kent got to talking and, well, you know.”

“No problem.”

“Face-reading again? Don’t you have this memorized by now? Lordy.”

Recenzii

Praise for BIG STONE GAP

"Charming . . . Readers would do well to fall into the nearest easy chair and savor the story."

— USA Today

"Delightfully quirky . . . chock-full of engaging, oddball characters and unexpected plot twists, this Gap is meant to be crossed."

— People (Book of the Week)

"As comforting as a mug of chamomile tea on a rainy Sunday."

— The New York Times Book Review

"A touching tale of a sleepy Southern town and a young woman on the brink of self-discovery and acceptance."

— Southern Living

"Ave Maria's spunky attitude, sardonic wit, and extravagant generosity compel you into her fan club . . . . Delightfully entertaining."

— Tampa Tribune

"A delightful tale of intimate community life [where] the characters are as real as the ones who live next door."

— Sunday Oklahoman

"In a sassy Southern voice, [Trigiani] creates honest, endearingly original characters."

— Glamour

From the Hardcover edition.

"Charming . . . Readers would do well to fall into the nearest easy chair and savor the story."

— USA Today

"Delightfully quirky . . . chock-full of engaging, oddball characters and unexpected plot twists, this Gap is meant to be crossed."

— People (Book of the Week)

"As comforting as a mug of chamomile tea on a rainy Sunday."

— The New York Times Book Review

"A touching tale of a sleepy Southern town and a young woman on the brink of self-discovery and acceptance."

— Southern Living

"Ave Maria's spunky attitude, sardonic wit, and extravagant generosity compel you into her fan club . . . . Delightfully entertaining."

— Tampa Tribune

"A delightful tale of intimate community life [where] the characters are as real as the ones who live next door."

— Sunday Oklahoman

"In a sassy Southern voice, [Trigiani] creates honest, endearingly original characters."

— Glamour

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The warm and very funny story of a small town is told by Ave Maria Mulligan, a 35-year-old self-proclaimed spinster, whose comfortable routine is about to be disrupted forever. "Funny, charming, and original".--Fannie Flagg.