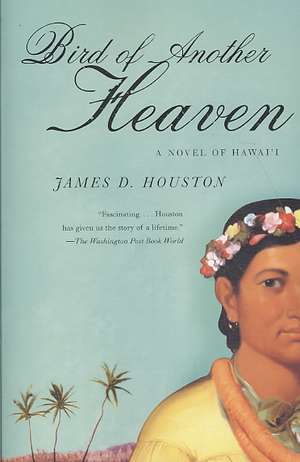

Bird of Another Heaven

Autor James D. Houstonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2008

When talk show host Sheridan Brody finds the journals of his great grandmother Nani Keala (aka Nancy Callahan), he uncovers a mythic, unknown tale. Nani, a shy girl from a remote Indian village, met the Hawai'ian king, David Kalakaua, on his grand progress by train across the United States in 1881, eventually returning with him to Honolulu. There, as his young ally and protégée, ever more assured and charming, she played an integral role in his attempt to revive the monarchy and spirit of his people and, eventually, witnessed the mysterious circumstances surrounding his downfall. Deeply engaging through its vivid portrayal of California and Hawai'i at the end of the nineteenth century, Bird of Another Heaven is a masterful portrait of an era long past.

Preț: 122.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 184

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.43€ • 24.46$ • 19.39£

23.43€ • 24.46$ • 19.39£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307388087

ISBN-10: 0307388085

Pagini: 337

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307388085

Pagini: 337

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

James D. Houston is the author of seven novels, including Continental Drift, Love Life, The Last Paradise—honored with a 1999 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation—and Snow Mountain Passage. His non-fiction works include Californians and Farewell to Manzanar, which he coauthored with his wife, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford, he has received the Humanities Prize, an NEA writing grant, and a Rockefeller Foundation residency. He lives in Santa Cruz, CA.

Extras

Born in a tribal village in the Sierra Nevada foothills, Nani Keala is the daughter of an Indian mother and Hawaiian father. In 1881, at age 17, she joins a local group of Hawaiians traveling to Sacramento to welcome David Kalakaua, the king of Hawaii, who is passing through California at the end of his round-the-world tour.

The Words Came

Though the last ones drank until after midnight, they were all up early for the final leg. In skiffs and launches they made a small fleet coasting south with the current, a couple of dozen Hawaiians and mixed-bloods, Indian wives, some children. They pulled into the wharf at Sacramento and from there walked three blocks to the Central Pacific depot. The king’s two railroad cars, which had arrived overnight from Denver, had been shunted off to a siding where a crowd had already gathered, curious townspeople for the most part, here to get their first glimpse of a ruling

monarch.

Nani stayed close to the Kinsman as he limped his way toward the side entrance of the first car. His nephew Makua, who went by “Mike,” had taken her arm, as if assigned as a personal escort. He was thickset and sure of himself, and lighter than Nani, with skin the shade of cocoa butter. He leaned down to murmur,“ This is a great day, you know. In Honolulu I have only seen the king from a great distance. They say he is a charming man.”

More islanders stood waiting there, three or four dozen, some with families, called in from nearby ranches and foothill towns and river towns farther downstream. They waved greetings to the Kinsman and his followers, then fell silent as the car door opened.

With no announcement or fanfare, a large Hawaiian stepped out onto the loading platform. He wore a black broadcloth morning coat, sharply creased trousers, a necktie around a high starched collar, but no hat atop his black and curly hair. He sported a moustache and muttonchops. At forty-four he looked ten years younger, a radiant and captivating man with unblemished olive-tinted skin, and his voice a melodious baritone.

“Aloha!” he said, with arms raised high. “Aloha kanaka maoli o Kaleponi!” (Greetings to my people here in California!)

While the white onlookers gazed in puzzled wonder, unsure what to make of this, the front ranks of islanders shouted out their loud reply. His voice itself was the sound of their distant homeland.

“Aloha, Kalakaua! Aloha! Aloha!”

In a burst of celebration they were waving, laughing and crying all at once, Nani among them, weeping for her father, who would have relished such a moment. This king was so much like him it was almost too much to bear–the same girth, the same eyes.

Gifts had appeared, to be heaped before him on the platform, flowers, fresh vegetables, a sack of walnuts, a box of apples, a cooked fish on a wooden platter. The Kinsman, who had left Hawai’i thirty years ago and never returned, was wiping his eyes as he stepped forward to chant in Hawaiian an oli aloha, a long chant of welcome.

As his last words dwindled, the celebrants waited for the king’s response, but the king too had to wait, so moved was he by this expression of love, by these gifts, by the sound of Hawaiian, the pulse of the chant. Into this waiting silence another voice rose. It was the cowboy who had composed the song about sailing down to meet the king. He had brought along a battered guitar. He sang five verses, and the king's eyes were glistening. As a fellow composer and performer he clapped in loud applause, urging the crowd to join him.

“Hana hou!” the king called out. “Hana hou!” (Encore! Play some more!)

The second time through, others from the river trip chimed in, drawing a wider round of applause, a few hoots and whistles of approval. The exuberant king thanked them for this song and for this welcome. In

English he proclaimed that on his trip across America he had stopped in many places, in Pennsylvania, in Lexington, Kentucky, in Omaha and Denver, but there had been no reception such as this, with such a show of his own people gathered together. Extending his arms and his smile to embrace the entire crowd, he thanked them all for coming to share his time in Sacramento, the capital of the wonderful state of California, a place he loved to visit for the beauties of its mountains and valleys and also because of its strong ties to Hawai’i.

Above the applause came a happy cry from one of the townspeople. “You better come back and see us, then!”

From the edge of the crowd another voice shouted,“But next time stay a little longer!”

Everyone laughed, including the king, and Nani was listening to his laugh, rumbling and resonant and full of delight. It could have been her father’s laugh. His voice could have been Keala’s voice, comforting, as smooth as honey.When the king spoke, it seemed he spoke to her alone. As he waved, ready to make his exit,he seemed to be waving to her.Some turn in the lifting of his hand was like her father’s hand beckoning, and she felt compelled to speak. She didn’t know what she meant to say, but the words came. A profound silence fell upon the yard and the loading dock as Nani’s throat vibrated with Hawaiian words. She stood straight, her chin lifted, and names rolled forth as if drawn out or guided by her hands, which swam in front of her chest like dancer’s hands. It was her family’s genealogy, and the voice speaking was much older than her own.

Kalakaua, poised on the upper step, had stopped in midstride.With one foot inside the doorway he regarded this young woman attentively, transfixed by what he heard. The sound of these names and the music of these words ringing above the railroad tracks of a foreign land, and the look of sweet innocence on the face of one whose voice had such an ancient ring–it filled his heart. When at last her voice subsided, Kalakaua did not move. Nani did not move. She let the tears stream down her face. No one moved or knew quite what to do. Finally he waved again to the silent crowd, then beckoned to the Kinsman, who moved closer for a whispered message. Moments later he and Nani were following the king.

Inside, the royal car was furnished like the lounge of a fine hotel, with carpeted floors, cushioned couches, plush upholstery, velvet draperies, a velvet-topped card table, and at one end a small bar with silver fittings. Near the bar a large white man in military dress had been watching

through parted drapes as the Hawaiians outside began to sing again. Now he approached the king.

“With all due respect, Your Majesty has a meeting in half an hour . . . the State Legislature . . .”

“Thank you, Charles.We will be there. They can’t start without me. And of course you know those gifts outside will have to be collected. It would be an insult to leave them.”

To his visitors the king said,“My chamberlain.”

The Kinsman, overwhelmed by the pomp and royal presence, managed to say,“Hello.”

Nani said,“I’m pleased to meet you,” with a little curtsy that seemed to amuse the king.

“Your Hawaiian is very good,” he said.“And I gather that you both speak English too?”

“Yes, we do,” the Kinsman said.

Once Charles had excused himself, with an impatient smile, stepping through a door and into the adjoining car, the king urged them to sit down. He had a few minutes now.

“I did not expect to hear such chanting in the city of Sacramento. I am curious about your family. Are you this woman’s father?”

“Her father was my cousin and my good friend, but he has passed on.”

“Au-we,” said the king, turning compassionate eyes toward Nani. “Perhaps I know some of your people Your father had several brothers. It seems we may have some ancestors in common.”

“I know,” she said.“He told me.”

“Ah, he told you this. And is that why you spoke the chant?”

“I do not know why I spoke it. Not since my father died have I said those names.”

For just an instant the king’s eyes opened wider, and Nani held his gaze with a kind of fearlessness that ruffled his composure. What passed between them is best described by Nani herself, as she wrote about this day many years later:

I often think of those first moments in his railroad car. When his eyes met mine there was a spark such as I had not seen before. His eyes were black as coal, but light came through them. Though he was older than me by nearly thirty years, at that moment he had a young man’s eyes. I felt I knew him. In those days I did not know how to say such things or describe them for myself. I know now that he had the same feeling and was surprised by what he saw in the eyes of someone my age. I knew many young women, he would one day confess to me, but they were all trained to attend to me as the king and to do my bidding in any way I requested. I thought of them as birds who flew down from the sky and into my life and out of my life.You did not have the training to know what was expected of you in the presence of a king. But you knew something else. You were a bird from another heaven. And that captivated me.

He asked Nani if she’d been to Hawai’i. She said she’d only heard stories. Suppose you had the chance to travel there, he said, would it interest you? It was my father’s dream, she said, but the islands are so very far away.

The king’s broad smile returned, a warm, expectant smile.

“Something has occurred to me. In Honolulu I have need for a kahili bearer, someone who can carry the royal standard from time to time. It must be a person of a certain known family background. You could be this person.”

Nani could no longer match his gaze, nor could she speak. His presence was suddenly overpowering, his physical size, the riveting command of his black eyes, which had taken on a conspiratorial glint. His smile filled the room. She looked down at the carpet, studying its floral swirls.

“We are a small party now,” he said. “My chamberlain. My aide. A few retainers.We will easily have room for one more on the ship.”

Still she couldn’t speak. This was too much to think about.

He asked the opinion of the Kinsman–as speechless now as Nani– who’d never heard of such a thing, a woman of this age, hardly more than a girl, setting out to travel with the king of Hawai’i. She was like a daughter to him, and granddaughter too. He wanted to object, yet it was not his place to question or contradict Kalakaua.

“Is your mother here today?” asked the king. “Do you have a husband? Or family to care for?”

At the word “husband,” her cheeks grew warm. The first thought of escaping Edward’s constant attention came with a rush of buoyant relief. She didn’t want the king to see her cheeks.With head inclined, still peering at the carpet, she said,“My mother also passed away. I have a younger

sister who lives up the river.”

Finding his voice, the Kinsman said,“We must talk of this among ourselves,Your Majesty. Nani teaches in the school. The younger children need her there.”

“Of course. I can see that in her. She already has the look of a wise teacher. But perhaps there is also work for her in Hawai’i.We encourage our people to come home, you know . . . if only for a short time.”

A door slid open, and the chamberlain appeared, officiously lifting a round silver watch from his vest pocket.“A carriage is waiting. We have fifteen minutes to get there.”

“What about tomorrow? What time do we leave?”

“Eight a.m. Tomorrow afternoon we connect with the last ferry from Oakland across to San Francisco.”

“I wish we could give you more time to consider this,” said the king. “But if you can join us, you must be here in the morning at eight o’clock sharp.”

Alarm filled the chamberlain’s ruddy face.“If who can join us?”

“I want you to meet Nani Keala. Perhaps a relative of mine.”

From the Hardcover edition.

The Words Came

Though the last ones drank until after midnight, they were all up early for the final leg. In skiffs and launches they made a small fleet coasting south with the current, a couple of dozen Hawaiians and mixed-bloods, Indian wives, some children. They pulled into the wharf at Sacramento and from there walked three blocks to the Central Pacific depot. The king’s two railroad cars, which had arrived overnight from Denver, had been shunted off to a siding where a crowd had already gathered, curious townspeople for the most part, here to get their first glimpse of a ruling

monarch.

Nani stayed close to the Kinsman as he limped his way toward the side entrance of the first car. His nephew Makua, who went by “Mike,” had taken her arm, as if assigned as a personal escort. He was thickset and sure of himself, and lighter than Nani, with skin the shade of cocoa butter. He leaned down to murmur,“ This is a great day, you know. In Honolulu I have only seen the king from a great distance. They say he is a charming man.”

More islanders stood waiting there, three or four dozen, some with families, called in from nearby ranches and foothill towns and river towns farther downstream. They waved greetings to the Kinsman and his followers, then fell silent as the car door opened.

With no announcement or fanfare, a large Hawaiian stepped out onto the loading platform. He wore a black broadcloth morning coat, sharply creased trousers, a necktie around a high starched collar, but no hat atop his black and curly hair. He sported a moustache and muttonchops. At forty-four he looked ten years younger, a radiant and captivating man with unblemished olive-tinted skin, and his voice a melodious baritone.

“Aloha!” he said, with arms raised high. “Aloha kanaka maoli o Kaleponi!” (Greetings to my people here in California!)

While the white onlookers gazed in puzzled wonder, unsure what to make of this, the front ranks of islanders shouted out their loud reply. His voice itself was the sound of their distant homeland.

“Aloha, Kalakaua! Aloha! Aloha!”

In a burst of celebration they were waving, laughing and crying all at once, Nani among them, weeping for her father, who would have relished such a moment. This king was so much like him it was almost too much to bear–the same girth, the same eyes.

Gifts had appeared, to be heaped before him on the platform, flowers, fresh vegetables, a sack of walnuts, a box of apples, a cooked fish on a wooden platter. The Kinsman, who had left Hawai’i thirty years ago and never returned, was wiping his eyes as he stepped forward to chant in Hawaiian an oli aloha, a long chant of welcome.

As his last words dwindled, the celebrants waited for the king’s response, but the king too had to wait, so moved was he by this expression of love, by these gifts, by the sound of Hawaiian, the pulse of the chant. Into this waiting silence another voice rose. It was the cowboy who had composed the song about sailing down to meet the king. He had brought along a battered guitar. He sang five verses, and the king's eyes were glistening. As a fellow composer and performer he clapped in loud applause, urging the crowd to join him.

“Hana hou!” the king called out. “Hana hou!” (Encore! Play some more!)

The second time through, others from the river trip chimed in, drawing a wider round of applause, a few hoots and whistles of approval. The exuberant king thanked them for this song and for this welcome. In

English he proclaimed that on his trip across America he had stopped in many places, in Pennsylvania, in Lexington, Kentucky, in Omaha and Denver, but there had been no reception such as this, with such a show of his own people gathered together. Extending his arms and his smile to embrace the entire crowd, he thanked them all for coming to share his time in Sacramento, the capital of the wonderful state of California, a place he loved to visit for the beauties of its mountains and valleys and also because of its strong ties to Hawai’i.

Above the applause came a happy cry from one of the townspeople. “You better come back and see us, then!”

From the edge of the crowd another voice shouted,“But next time stay a little longer!”

Everyone laughed, including the king, and Nani was listening to his laugh, rumbling and resonant and full of delight. It could have been her father’s laugh. His voice could have been Keala’s voice, comforting, as smooth as honey.When the king spoke, it seemed he spoke to her alone. As he waved, ready to make his exit,he seemed to be waving to her.Some turn in the lifting of his hand was like her father’s hand beckoning, and she felt compelled to speak. She didn’t know what she meant to say, but the words came. A profound silence fell upon the yard and the loading dock as Nani’s throat vibrated with Hawaiian words. She stood straight, her chin lifted, and names rolled forth as if drawn out or guided by her hands, which swam in front of her chest like dancer’s hands. It was her family’s genealogy, and the voice speaking was much older than her own.

Kalakaua, poised on the upper step, had stopped in midstride.With one foot inside the doorway he regarded this young woman attentively, transfixed by what he heard. The sound of these names and the music of these words ringing above the railroad tracks of a foreign land, and the look of sweet innocence on the face of one whose voice had such an ancient ring–it filled his heart. When at last her voice subsided, Kalakaua did not move. Nani did not move. She let the tears stream down her face. No one moved or knew quite what to do. Finally he waved again to the silent crowd, then beckoned to the Kinsman, who moved closer for a whispered message. Moments later he and Nani were following the king.

Inside, the royal car was furnished like the lounge of a fine hotel, with carpeted floors, cushioned couches, plush upholstery, velvet draperies, a velvet-topped card table, and at one end a small bar with silver fittings. Near the bar a large white man in military dress had been watching

through parted drapes as the Hawaiians outside began to sing again. Now he approached the king.

“With all due respect, Your Majesty has a meeting in half an hour . . . the State Legislature . . .”

“Thank you, Charles.We will be there. They can’t start without me. And of course you know those gifts outside will have to be collected. It would be an insult to leave them.”

To his visitors the king said,“My chamberlain.”

The Kinsman, overwhelmed by the pomp and royal presence, managed to say,“Hello.”

Nani said,“I’m pleased to meet you,” with a little curtsy that seemed to amuse the king.

“Your Hawaiian is very good,” he said.“And I gather that you both speak English too?”

“Yes, we do,” the Kinsman said.

Once Charles had excused himself, with an impatient smile, stepping through a door and into the adjoining car, the king urged them to sit down. He had a few minutes now.

“I did not expect to hear such chanting in the city of Sacramento. I am curious about your family. Are you this woman’s father?”

“Her father was my cousin and my good friend, but he has passed on.”

“Au-we,” said the king, turning compassionate eyes toward Nani. “Perhaps I know some of your people Your father had several brothers. It seems we may have some ancestors in common.”

“I know,” she said.“He told me.”

“Ah, he told you this. And is that why you spoke the chant?”

“I do not know why I spoke it. Not since my father died have I said those names.”

For just an instant the king’s eyes opened wider, and Nani held his gaze with a kind of fearlessness that ruffled his composure. What passed between them is best described by Nani herself, as she wrote about this day many years later:

I often think of those first moments in his railroad car. When his eyes met mine there was a spark such as I had not seen before. His eyes were black as coal, but light came through them. Though he was older than me by nearly thirty years, at that moment he had a young man’s eyes. I felt I knew him. In those days I did not know how to say such things or describe them for myself. I know now that he had the same feeling and was surprised by what he saw in the eyes of someone my age. I knew many young women, he would one day confess to me, but they were all trained to attend to me as the king and to do my bidding in any way I requested. I thought of them as birds who flew down from the sky and into my life and out of my life.You did not have the training to know what was expected of you in the presence of a king. But you knew something else. You were a bird from another heaven. And that captivated me.

He asked Nani if she’d been to Hawai’i. She said she’d only heard stories. Suppose you had the chance to travel there, he said, would it interest you? It was my father’s dream, she said, but the islands are so very far away.

The king’s broad smile returned, a warm, expectant smile.

“Something has occurred to me. In Honolulu I have need for a kahili bearer, someone who can carry the royal standard from time to time. It must be a person of a certain known family background. You could be this person.”

Nani could no longer match his gaze, nor could she speak. His presence was suddenly overpowering, his physical size, the riveting command of his black eyes, which had taken on a conspiratorial glint. His smile filled the room. She looked down at the carpet, studying its floral swirls.

“We are a small party now,” he said. “My chamberlain. My aide. A few retainers.We will easily have room for one more on the ship.”

Still she couldn’t speak. This was too much to think about.

He asked the opinion of the Kinsman–as speechless now as Nani– who’d never heard of such a thing, a woman of this age, hardly more than a girl, setting out to travel with the king of Hawai’i. She was like a daughter to him, and granddaughter too. He wanted to object, yet it was not his place to question or contradict Kalakaua.

“Is your mother here today?” asked the king. “Do you have a husband? Or family to care for?”

At the word “husband,” her cheeks grew warm. The first thought of escaping Edward’s constant attention came with a rush of buoyant relief. She didn’t want the king to see her cheeks.With head inclined, still peering at the carpet, she said,“My mother also passed away. I have a younger

sister who lives up the river.”

Finding his voice, the Kinsman said,“We must talk of this among ourselves,Your Majesty. Nani teaches in the school. The younger children need her there.”

“Of course. I can see that in her. She already has the look of a wise teacher. But perhaps there is also work for her in Hawai’i.We encourage our people to come home, you know . . . if only for a short time.”

A door slid open, and the chamberlain appeared, officiously lifting a round silver watch from his vest pocket.“A carriage is waiting. We have fifteen minutes to get there.”

“What about tomorrow? What time do we leave?”

“Eight a.m. Tomorrow afternoon we connect with the last ferry from Oakland across to San Francisco.”

“I wish we could give you more time to consider this,” said the king. “But if you can join us, you must be here in the morning at eight o’clock sharp.”

Alarm filled the chamberlain’s ruddy face.“If who can join us?”

“I want you to meet Nani Keala. Perhaps a relative of mine.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Fascinating. . . . Houston has given us the story of a lifetime.” —The Washington Post Book World“Poignant. . . . [Houston's subjects] have never been written about with more insight.” —The Oregonian“[Bird of Another Heaven], filled with real historical figures, richly reconceives the demise of the Hawaiian monarchy.” —Entertainment Weekly“Sweeping….a panoramic saga that spans two centuries.” —Sacramento Bee