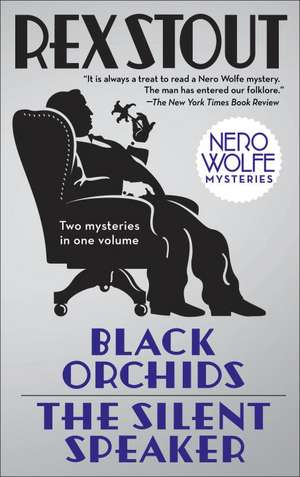

Black Orchids/The Silent Speaker: Nero Wolfe Mysteries: Nero Wolfe

Autor Rex Stouten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

“Nero Wolfe towers over his rivals...he is an exceptional character creation.” —New Yorker A grand master of the form, Rex Stout is one of America’s greatest mystery writers, and his literary creation Nero Wolfe is one of fiction’s greatest detectives. In this double helping of classic Nero Wolfe mysteries, Stout presents the arrogant, gourmandizing, sedentary sleuth and his trusty man-about-town, Archie Goodwin, with a pair of delectable murders that no connoisseur of the whodunit could possibly resist.

BLACK ORCHIDS

Not much can get Wolfe to leave his comfortable brownstone, but the showing of a rare black orchid lures him to a flower show. Unfortunately, the much-anticipated event is soon overshadowed by a murder as daring as it is sudden. It’s a case of weeding out a cunning killer who can turn up anywhere—and Wolfe must do it quickly. Because a second case awaits his urgent attention: a society widow on a mailing list of poison-pen letters leading to a plot as dark as any orchid Wolfe has ever encountered.

THE SILENT SPEAKER

When a government power broker scheduled to speak before an influential group of millionaires turns up dead, Nero Wolfe grudgingly takes the case—even as his own financial affairs teeter toward ruin. Soon a second victim is discovered, a missing stenographer’s tape causes a panic, and a dead man speaks, after a fashion. As the business world demands answers, the great detective baits a trap to net a killer worth his weight in gold.

Preț: 80.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 121

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.47€ • 16.15$ • 12.80£

15.47€ • 16.15$ • 12.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-22 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553386554

ISBN-10: 0553386557

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 134 x 212 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Nero Wolfe

ISBN-10: 0553386557

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 134 x 212 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Nero Wolfe

Notă biografică

Rex Stout (1886-1975) wrote hundreds of short stories, novelas, and full-length mystery novels, most featuring his two indelible characters, the peerless detective Nero Wolfe and his handy sidekick, Archie Goodwin.

Extras

Chapter One

What Are the Odds in Times like These?

The self-owned and -operated business is the freest life in the world.—Paul Hawken

When I answered the phone, I was startled to hear a man whispering, “Hi, this is Scott. I’m calling from work, but I had to talk to you.”

“Sure,” I said.

“I want to be JJ,” he whispered back.

“Jay Jay?” I thought. “Who’s Jay Jay? Why’s he telling me this?” Before I could ask, he went on to explain that he loathed his job and longed to be “joyfully jobless.” We made an appointment for him to call back when he could talk out loud.

Scott’s not the only one, of course. One memorable message arrived in my email box with the title “Cowering in my cubicle.”

Every day I hear from people who have come to the same conclusion. Some have no idea what they want to do instead of having a conventional job. Others have an idea but don’t know how to get started. And recently, more people who find themselves without a job are looking at alternatives and options they may not have considered before.

My own journey began when I was in the midst of a second career and found myself as miserable as I had been in my first job. Ironically, I had landed a position as a job counselor, working for the Minnesota Department of Employment Services. Shortly after arriving there (and already realizing I was not cut out to be a bureaucrat), I discovered a gigantic book called The Dictionary of Occupational Titles. This book contains tens of thousands of job descriptions. “Surely,” I thought, “if I read this book, I’ll find my lost career.” In any free moment, I’d grab the dictionary and begin reading. The more I read, the more discouraged I became.

“There’s nothing here I want to do,” I lamented. I feared I was doomed to a life of drudgery.

That’s not how my story ends, of course. I discovered that I could create my own work, be my own boss, and eventually get paid generously to do the things I loved. Along the way, I made wonderful new friends and plenty of mistakes. There were moments when I thought I had taken leave of my senses—and many more moments when I could hardly believe my good fortune. What I never imagined back at the beginning was that I’d end up teaching thousands of people how to leave behind the nine-tofive world and start building something on their own.

Of course, the people coming to my self- employment seminars and teleclasses bring plenty of questions with them, but the one I get asked the most seemingly has nothing to do with making a living without a job. The most frequently asked question I’ve ever received came after I relocated three years ago. “Why did you move to Las Vegas?” is the one I hear over and over.

The runner-up is “Do you actually think anyone can be selfemployed?” Almost always, the person asking the question sounds shocked or at least skeptical. I have several answers to the first question, but my usual response to the second has been “Yes, I think anyone can be self- employed, but not everyone will be.” As of this writing, there seems to be another topic that’s grabbed everyone’s attention: the current and confusing economic recession. Everything, from news stories to personal decisions, seems to be filtered through this growing crisis. So, of course, the question I’m hearing more often these days is “Isn’t this a dangerous time to start a business?”

That’s certainly a fair question, and I can answer it as only a Las Vegan might: “Have you considered the odds?” Unlike the rest of the world, here in Las Vegas our casinos boldly post the odds, warning that they’re not in your favor if you’re about to gamble. That doesn’t deter folks who hope to beat those odds.

One of the common assumptions about self- employment is that it is intrinsically risky. I’d like to suggest that you think about the odds of success if you are making a life change. How do you calculate odds? Not being a gambler myself, odds weren’t something I gave much thought to until I was fretting about the possibility of a giant calamity, such as being devastated by an earthquake or some natural disaster. I mentioned my qualms to my sister Margaret, who calmly asked, “Don’t you know the odds are always in your favor?” I was startled by that answer and shook my head, so she explained further, “Haven’t you noticed that even in large catastrophes, more people survive than don’t?”

That was a new insight to me, so I began looking for evidence. Sure enough, Margaret was absolutely right. No matter what crisis is going on, more people are unaffected than harmed. Knowing this has kept me calm in situations that previously would have scared the wits out of me.

I’ve also considered that if the odds are in my favor—and yours—in times of calamity, how much more must they be on our side when we’re creating something about which we care deeply? Even though a topsy- turvy economy has an impact on everyone at some level, many will be far less affected than others. And some will come through it better than before it happened. Let’s look at how the odds are shifting.

Most of us grew up in a Big Is Better culture. Our parents and older siblings seemed to draw their self- esteem from working for giant companies. It didn’t matter that these companies did not possess a soul or that their workers were discouraged from thinking creatively. Spending their days in a cubicle became socially acceptable. The company was big and that was impressive. As we watch the collapse of gigantic institutions (the list gets longer every day), we can join the doom-and-gloom crowd and see this as the end of our world as we know it. Or we can see it as a groundswell of change that is bringing with it unimagined opportunities, opportunities that will be the basis of the Small Is Better culture that’s been quietly emerging for several years. More than a decade ago, trendspotter Faith Popcorn pointed out that more and more of us would move out of corporate confines and into our own businesses. In her book The Popcorn Report, she says that satisfaction and having control over our own time are going to be top priorities. Popcorn writes, “After a shocking period of corporate greed, after years of commuting, people are dreaming of renovating old houses, starting hands-on entrepreneurial businesses, or even doing what they’ve built their careers doing—but on their own time and terms. We are asking ourselves what is real, what is honest, what is quality, what is really important. . . . Nobody works harder, or happier, or more productively, than people working for themselves.”

So why haven’t we all figured that out? Could it be that making a living without a job is almost never an option offered by guidance counselors? Why do colleges continue to turn out corporate workers when the trend is in a different direction? Have the myths about risk scared us away?

Despite living in the shadow of an old paradigm about work, every day more of us decide to inhabit this new creative minority. A few years ago, I became a Junior Achievement volunteer. For six weeks, I spent an hour every week with a group of lively fourth-graders. The first day I was there, I introduced myself to the class and told them about my business. Then I asked if anyone knew somebody who ran a small business from home. Nearly two-thirds of the kids raised their hands. That probably wouldn’t have happened even a decade earlier.

Now hardly a day passes when I don’t read about or meet someone who is happily working on their own. At the end of 2003, a London newspaper headline proclaimed, “Huge Rise in Workers Who Go It Alone.” The article stated that an estimated 300,000 people in the U.K. had decided to abandon their jobs to go out on their own just that year.

The U.S. Census Bureau, in a report from the late 1990s, shared this affirming information: “In the past, a homebased business was viewed as a side business operated primarily as a hobby or as a source of secondary income. The data contained in this study show that assertion to be inaccurate. The researchers’ findings demonstrate how the home has become a hub of business activity, entrepreneurship, and business creation. Sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations added $2.9 trillion to the economy, with homebased firms contributing $314 billion, or 11 percent.” The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) reports that every year there are dramatic increases in the numbers of home business operations.

What does a tiny business offer that a big one doesn’t? Why are the odds in favor of the small enterprise? To begin with, small is flexible. Times change, and smart small businesses change with them. No slow bureaucracy needs to be approached for permission before change can be implemented. The ability and willingness to change as necessary ups the odds that a company will weather tough times.

Small is accessible. Your guidance counselor may have forgotten to tell you this, but the free enterprise system is wonderfully open to anyone who wishes to participate, providing their intentions are honorable. You don’t have to look very far to see entrepreneurs who are young, old, educated, uneducated, immigrants, physically challenged, women, social activists, and introverts. That list doesn’t even begin to describe the array of people who have found success working on their own.

Small is diversified. Financial gurus have always advised investors to diversify their portfolios. That same advice can be applied to earning that money. In this book, you’ll be introduced to the idea of creating Multiple Profit Centers. Once you understand the value of having several income sources, you’ll be eager to start building your own portfolio of moneymakers. Not only will this affect your earnings, it will also eliminate the Eggs in One Basket syndrome (which is devastating if the one and only income source disappears).

Small can be frugal when necessary. Anyone who has built a business on a shoestring knows how to be thrifty. In fact, some folks discover how creative they can be when they tap into their imagination to solve problems.

One of my favorite entrepreneurial role models was Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop. In her early days in business, she had no money to advertise, so she created attention- getting signs for her shop windows to draw customers in. Even after The Body Shop was an international chain, the company never spent a penny for advertising but found creative ways to let people know it was there.

Spendthrifts aren’t nearly as good at improvising. Odds favor the frugal.

Small is less risky. Author and entrepreneur Seth Godin says, “For the last six years, I’ve had exactly one employee. Me. This has changed my life in ways that I hadn’t predicted. . . . I can write an e-book and launch it in some crazy way and just see what happens . . . If you don’t have to bet the farm on every launch, you’re way more likely to launch more, which vastly increases your odds.”

What Are the Odds in Times like These?

The self-owned and -operated business is the freest life in the world.—Paul Hawken

When I answered the phone, I was startled to hear a man whispering, “Hi, this is Scott. I’m calling from work, but I had to talk to you.”

“Sure,” I said.

“I want to be JJ,” he whispered back.

“Jay Jay?” I thought. “Who’s Jay Jay? Why’s he telling me this?” Before I could ask, he went on to explain that he loathed his job and longed to be “joyfully jobless.” We made an appointment for him to call back when he could talk out loud.

Scott’s not the only one, of course. One memorable message arrived in my email box with the title “Cowering in my cubicle.”

Every day I hear from people who have come to the same conclusion. Some have no idea what they want to do instead of having a conventional job. Others have an idea but don’t know how to get started. And recently, more people who find themselves without a job are looking at alternatives and options they may not have considered before.

My own journey began when I was in the midst of a second career and found myself as miserable as I had been in my first job. Ironically, I had landed a position as a job counselor, working for the Minnesota Department of Employment Services. Shortly after arriving there (and already realizing I was not cut out to be a bureaucrat), I discovered a gigantic book called The Dictionary of Occupational Titles. This book contains tens of thousands of job descriptions. “Surely,” I thought, “if I read this book, I’ll find my lost career.” In any free moment, I’d grab the dictionary and begin reading. The more I read, the more discouraged I became.

“There’s nothing here I want to do,” I lamented. I feared I was doomed to a life of drudgery.

That’s not how my story ends, of course. I discovered that I could create my own work, be my own boss, and eventually get paid generously to do the things I loved. Along the way, I made wonderful new friends and plenty of mistakes. There were moments when I thought I had taken leave of my senses—and many more moments when I could hardly believe my good fortune. What I never imagined back at the beginning was that I’d end up teaching thousands of people how to leave behind the nine-tofive world and start building something on their own.

Of course, the people coming to my self- employment seminars and teleclasses bring plenty of questions with them, but the one I get asked the most seemingly has nothing to do with making a living without a job. The most frequently asked question I’ve ever received came after I relocated three years ago. “Why did you move to Las Vegas?” is the one I hear over and over.

The runner-up is “Do you actually think anyone can be selfemployed?” Almost always, the person asking the question sounds shocked or at least skeptical. I have several answers to the first question, but my usual response to the second has been “Yes, I think anyone can be self- employed, but not everyone will be.” As of this writing, there seems to be another topic that’s grabbed everyone’s attention: the current and confusing economic recession. Everything, from news stories to personal decisions, seems to be filtered through this growing crisis. So, of course, the question I’m hearing more often these days is “Isn’t this a dangerous time to start a business?”

That’s certainly a fair question, and I can answer it as only a Las Vegan might: “Have you considered the odds?” Unlike the rest of the world, here in Las Vegas our casinos boldly post the odds, warning that they’re not in your favor if you’re about to gamble. That doesn’t deter folks who hope to beat those odds.

One of the common assumptions about self- employment is that it is intrinsically risky. I’d like to suggest that you think about the odds of success if you are making a life change. How do you calculate odds? Not being a gambler myself, odds weren’t something I gave much thought to until I was fretting about the possibility of a giant calamity, such as being devastated by an earthquake or some natural disaster. I mentioned my qualms to my sister Margaret, who calmly asked, “Don’t you know the odds are always in your favor?” I was startled by that answer and shook my head, so she explained further, “Haven’t you noticed that even in large catastrophes, more people survive than don’t?”

That was a new insight to me, so I began looking for evidence. Sure enough, Margaret was absolutely right. No matter what crisis is going on, more people are unaffected than harmed. Knowing this has kept me calm in situations that previously would have scared the wits out of me.

I’ve also considered that if the odds are in my favor—and yours—in times of calamity, how much more must they be on our side when we’re creating something about which we care deeply? Even though a topsy- turvy economy has an impact on everyone at some level, many will be far less affected than others. And some will come through it better than before it happened. Let’s look at how the odds are shifting.

Most of us grew up in a Big Is Better culture. Our parents and older siblings seemed to draw their self- esteem from working for giant companies. It didn’t matter that these companies did not possess a soul or that their workers were discouraged from thinking creatively. Spending their days in a cubicle became socially acceptable. The company was big and that was impressive. As we watch the collapse of gigantic institutions (the list gets longer every day), we can join the doom-and-gloom crowd and see this as the end of our world as we know it. Or we can see it as a groundswell of change that is bringing with it unimagined opportunities, opportunities that will be the basis of the Small Is Better culture that’s been quietly emerging for several years. More than a decade ago, trendspotter Faith Popcorn pointed out that more and more of us would move out of corporate confines and into our own businesses. In her book The Popcorn Report, she says that satisfaction and having control over our own time are going to be top priorities. Popcorn writes, “After a shocking period of corporate greed, after years of commuting, people are dreaming of renovating old houses, starting hands-on entrepreneurial businesses, or even doing what they’ve built their careers doing—but on their own time and terms. We are asking ourselves what is real, what is honest, what is quality, what is really important. . . . Nobody works harder, or happier, or more productively, than people working for themselves.”

So why haven’t we all figured that out? Could it be that making a living without a job is almost never an option offered by guidance counselors? Why do colleges continue to turn out corporate workers when the trend is in a different direction? Have the myths about risk scared us away?

Despite living in the shadow of an old paradigm about work, every day more of us decide to inhabit this new creative minority. A few years ago, I became a Junior Achievement volunteer. For six weeks, I spent an hour every week with a group of lively fourth-graders. The first day I was there, I introduced myself to the class and told them about my business. Then I asked if anyone knew somebody who ran a small business from home. Nearly two-thirds of the kids raised their hands. That probably wouldn’t have happened even a decade earlier.

Now hardly a day passes when I don’t read about or meet someone who is happily working on their own. At the end of 2003, a London newspaper headline proclaimed, “Huge Rise in Workers Who Go It Alone.” The article stated that an estimated 300,000 people in the U.K. had decided to abandon their jobs to go out on their own just that year.

The U.S. Census Bureau, in a report from the late 1990s, shared this affirming information: “In the past, a homebased business was viewed as a side business operated primarily as a hobby or as a source of secondary income. The data contained in this study show that assertion to be inaccurate. The researchers’ findings demonstrate how the home has become a hub of business activity, entrepreneurship, and business creation. Sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations added $2.9 trillion to the economy, with homebased firms contributing $314 billion, or 11 percent.” The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) reports that every year there are dramatic increases in the numbers of home business operations.

What does a tiny business offer that a big one doesn’t? Why are the odds in favor of the small enterprise? To begin with, small is flexible. Times change, and smart small businesses change with them. No slow bureaucracy needs to be approached for permission before change can be implemented. The ability and willingness to change as necessary ups the odds that a company will weather tough times.

Small is accessible. Your guidance counselor may have forgotten to tell you this, but the free enterprise system is wonderfully open to anyone who wishes to participate, providing their intentions are honorable. You don’t have to look very far to see entrepreneurs who are young, old, educated, uneducated, immigrants, physically challenged, women, social activists, and introverts. That list doesn’t even begin to describe the array of people who have found success working on their own.

Small is diversified. Financial gurus have always advised investors to diversify their portfolios. That same advice can be applied to earning that money. In this book, you’ll be introduced to the idea of creating Multiple Profit Centers. Once you understand the value of having several income sources, you’ll be eager to start building your own portfolio of moneymakers. Not only will this affect your earnings, it will also eliminate the Eggs in One Basket syndrome (which is devastating if the one and only income source disappears).

Small can be frugal when necessary. Anyone who has built a business on a shoestring knows how to be thrifty. In fact, some folks discover how creative they can be when they tap into their imagination to solve problems.

One of my favorite entrepreneurial role models was Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop. In her early days in business, she had no money to advertise, so she created attention- getting signs for her shop windows to draw customers in. Even after The Body Shop was an international chain, the company never spent a penny for advertising but found creative ways to let people know it was there.

Spendthrifts aren’t nearly as good at improvising. Odds favor the frugal.

Small is less risky. Author and entrepreneur Seth Godin says, “For the last six years, I’ve had exactly one employee. Me. This has changed my life in ways that I hadn’t predicted. . . . I can write an e-book and launch it in some crazy way and just see what happens . . . If you don’t have to bet the farm on every launch, you’re way more likely to launch more, which vastly increases your odds.”

Recenzii

"It is always a treat to read a Nero Wolfe mystery. The man has entered our folklore.” —New York Times Book Review