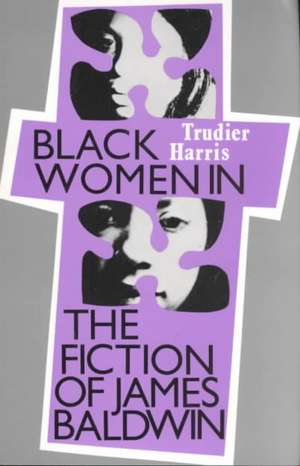

Black Women in the Fiction of James Baldwin

Autor Trudier Harrisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 iun 1987

Black women in the early fiction, responding to their elders as well as to religious influences, see their lives in terms of duty as wives, mothers, sisters, and lovers. Failure in any of these roles leads to feelings of guilt and the expectation of damnation. In his later works, Baldwin adopts a new point of view, acknowledging complex extenuating circumstances in lieu of pronouncing moral judgement. Female characters in works written at this stage eventually come to believe that the church affords no comfort.

Baldwin subsequently makes villains of some female churchgoers, and caring women who do not attend church become his most attractive characters. Still later in Baldwin's career, a woman who frees herself of guilt by moving completely beyond the church attains greater contentment than almost all of her counterparts in the earlier works.

Preț: 158.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 238

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.34€ • 31.56$ • 25.05£

30.34€ • 31.56$ • 25.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-01 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780870495342

ISBN-10: 0870495348

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

ISBN-10: 0870495348

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

Notă biografică

Trudier Harris is an author specializing in African American literature and folklore. Professor emerita from the University of Alabama, she earned her bachelor's degree from Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and her master's and PhD from The Ohio State University. Some of her other books include From Mammies to Militants: Domestics in Black American Literature, Fiction and Folklore: The Novels of Toni Morrison; and The Power of the Porch: The Storyteller's Craft in Zora Neale Hurston.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

The many reactions I have received to my study of James Baldwin's treatment of black women in his fiction have encouraged me in my belief that such a work is necessary and timely. Individuals with whom I spoke who remembered the women in Baldwin's fiction were intrigued that I wanted to do a detailed study of these characters. Scholars more familiar with issues and themes than characters were concerned to know if the women were prominent enough to deserve a separate study and, if so, what I would say about them. Frequently persons less familiar with Baldwin's works could not remember the names of the female characters, and they often asked questions about which works were to be included in the study.

On occasion, I was surprised to discover that a writer of Baldwin's reputation evoked such vague memories from individuals in the scholarly community, most of whom maintained that they had read one or more of his fictional works. When I began a thorough examination of Baldwin scholarship, however, some of that reaction became clearer. Baldwin seems to be read at times for the sensationalism readers anticipate in his work, but his treatment in scholarly circles is not commensurate to that claim to sensationalism or to his more solidly justified literary reputation. It was discouraging, therefore, to think that one of America's best-known writers, and certainly one of its best-known black writers, has not attained a more substantial place in the scholarship on Afro-American writers. I am hopeful, therefore, that this study of the black women characters in Baldwin's fiction may inspire further discussions and promote additional detailed treatments of his works.

Within the limited number of critical volumes devoted to Baldwin, it is not surprising to discover that the female characters are the subjects of only a minute portion of them. Though Baldwin has been writing for over thirty years and has more than sixteen books to his credit, only three book-length critical studies of his work exist.1 Another book-length study is primarily biographical in orientation.2 Of these studies, none focuses exclusively on fiction, which is the genre in which Baldwin has produced most,3 and only one was published after 1978. Two collections of critical essays have been published, both before 1978.4 Only one critic distinguishes herself in the bulk of the criticism by giving more than cursory attention to the black women who populate Baldwin's fiction.5 For the other critics, these women, in spite of their roles as central or shaping forces in the lives of the male characters, have been relegated to a secondary or nonexistent place in their discussions of the fiction.

Black women such as Florence and Elizabeth in Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) have received the most critical exposure be cause parts of the novel are narrated from their points of view, but the angle of vision of the criticism has focused consistently on John and Gabriel; the women have not commanded attention in their own right as female characters. Ida, in Another Country (1962), has been judged a central character by two or three critics, but they have not followed through on their evaluations to give more than a few para graphs of commentary; she usually receives only passing attention. Women in Going to Meet the Man (1965), even Ruth, from whose point of view "Come Out the Wilderness" is narrated, have essentially been ignored. Tish (Clementine), who narrates If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), has been the subject of a couple of articles, but she has also been viewed as an unconvincing narrator. Julia and other women in Just Above My Head (1979) have been mentioned in review articles and plot summaries. Publication dates of Just Above My Head and If Beale Street Could Talk are undoubtedly relevant in considering the quantity of criticism that has appeared so far, in terms of treatment, but most of it continues the trend of giving Baldwin's black women characters only minimal attention.

The types as well as the limited number of book-length treatments of Baldwin's works underscore the fact that a major American writer has not received the intensive and extensive evaluation warranted by his prominence. While this study is designed to fill a gap in Baldwin scholarship, it has the equally important purpose of treating characters often neglected in specific discussions of Baldwin as well as in more generalized discussions of American and black American literature. Categories I define and analyses I offer about Baldwin's black female characters are derived from careful examination of Go Tell It on the Mountain, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man, If Beale Street Could Talk, and Just Above My Head.6

The black women Baldwin treats in his works play a number of roles, several of which overlap. Whatever their role, most of the women believe themselves to be guilty of some crime or condition of existence that demands their doing penance. At times the women are spiritual outcasts, psychological ghetto dwellers in a familial, sexual, religious world where their suffering does not lead to redemption. Whatever her position, no black woman in Baldwin's fiction is ultimately, continuously happy, though a few, like Julia in Just Above My Head, reach a state of contentment. Further, few of them are spiritually healthy. Their guilt for the "crimes" that they can articulate only through suffering is often tied to their evaluations of past actions in a "sinful" life. Because of their willingness to suffer, they are therefore frequently doomed to exist in psychological discomfort, in self-accusation and repression. This book examines the sources of their guilt, its manifestations in their daily lives, and the process of extrication through which the few women who do so manage to escape their guilt.

The sense of guilt the women feel is often tied to their desire to break away from roles that have been defined for them, or to their failure to fulfill a role. Almost all of the roles in which we find black women in Baldwin's fiction are traditional ones-mothers, sisters, lovers, wives-and almost all of them are roles of support for the male characters. The most prominent women we associate with Bald win's fiction are those who are solidly within the tradition of the fundamentalist church as it exists in black communities. These women may be classified as churchgoers, and appear from Go Tell It on the Mountain to Just Above My Head. The women in this cate gory come closer to being stereotypes than perhaps any others in Baldwin's works. They are usually described as large, buxom, very dark-skinned, and middle-aged or older. Their long years of faithful attendance and their tending to the souls of younger church members have won them a respectable status in the church. Usually models of Christian faith and actions to nonmembers of the church, these long suffering women are best exemplified by Praying Mother Washington and Sister McCandless in Go Tell It on the Mountain. They remind us of the matriarchal Mama Lena Younger in Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun in the unwavering quality of their faith and in their concern that other members of their immediate or church family should come into or remain within the fold of the church.

These women, like Mrs. Hunt in If Beale Street Could Talk, may be almost fanatical in the fervor with which they carry out their commitment to the church and to God. Deborah, in Go Tell It on the Mountain, clings to the church as if it is her last chance for life. Although she is younger than the other women, her life experiences have aged her prematurely, and she is therefore as "old" in faith as Praying Mother Washington. She is consistent in witnessing for the Lord, in attending to the sick and the dead, and in fervently uttering "amens" in response to Gabriel's and other preachers' sermons. These fanatical church women may on occasion make the very example of their piety a threat to those around them. People who would make fun of Deborah's plainness or of the fact that she has been raped are awed into silence by the faith she exhibits. Mrs. Hunt specifically becomes a threat to the young people around her, as do Sister Mc Candless and Sister Daniels in "The Outing." These women may also become so single-mindedly dedicated to the church that, like Mrs. Hunt, they neglect their families in a literal adaptation of the biblical injunction to sacrifice even husband, son, and daughter for one's belief in God.

A subdivision of the category of churchgoers, represented by women slightly younger than those described above, would be the one into which Elizabeth Grimes fits in Go Tell It on the Mountain. By virtue of the fact that her husband is a preacher and a deacon, Elizabeth must have a role in the church. She is torn, therefore, between what form demands and what she knows her own heart to believe. She is certainly not without faith, but she is not as believing or as committed as Deborah and Mrs. Hunt are. She tries to find the blend of raising her children within the church and minding her own soul; she does not reject one in favor of the other. She is much more silent and passive than the first category of churchgoers. Although we see her on her knees praying in church, we never hear her so much as utter an "amen" during the services she frequently attends. On rare occasions, these women in the church extend their roles beyond those of support to ones of leadership. Praying Mother Washington has a recognized position of respect in Go Tell It on the Mountain; she is "a powerful evangelist and very widely known."7 Sister Daniels, a member of the same church, has been "blessed" with a "mighty voice with which to sing and preach," and she is "going out soon into the field" (p. 57). The most prominent of the female leaders in the churches that appear in Baldwin's works, however, is Julia Miller in Just Above My Head. As a seven-year-old child prodigy preacher, she is responsible for bringing many souls to Christ.

As leaders and as supporters, the women in the church subdivide into true believers and hypocrites, which in turn affects their portrayal as women. Even among the true believers, some are presented more seriously than others; Deborah is portrayed straightforwardly, but Sister Daniels is sometimes presented in slightly derogatory ways. Mrs. Hunt is obviously a hypocrite at whom we are encouraged to laugh. How the women are presented is affected in part by the period in which the work appeared and by the nature of Baldwin's politics at the time.

Baldwin's portrayal of mothers overlaps with his portrayal of churchgoers. Indeed, many of the women in the church who have no children of their own assume the role of mother to the young people in their churches. Several of the mothers, like the churchgoing women, are long-suffering. They range from hypersensitive Elizabeth, from whom her son John must sense her moods and desires, to supportive Sharon Rivers in If Beale Street Could Talk. The atypical portrait of the mother is Mrs. Hunt, also in Beale Street, who rejects her son. The most attractive mothers are the ones who would give everything for their children, either in quiet ways, as Elizabeth does with John, or in very vocal, aggressive ways, as Sharon Rivers does with her daughter Tish. Mrs. Hunt, by contrast, is most unattractive as a mother because she fails to support, because she refuses to allow sacrifice for her family to become part of her personality.

Women as sisters are also important to Baldwin. They range from Florence in Go Tell It on the Mountain, to Ida in Another Country, to Ernestine, Adrienne and Sheila in If Beale Street Could Talk, to Julia in Just Above My Head. Sisters, like mothers, are most attractive when they are in helpful roles to other members of their families, particularly the males. Florence believes she has trouble partly because she feels she has mocked her brother Gabriel's ministry, while Ernestine is a positive image because of the sacrificial nature of her support for Tish and Fonny. Adrienne and Sheila are superficial fluffs, mere window dressing, because they care more for aristocratic manners than for their brother Fonny. Julia initially causes many problems for her younger brother Jimmy, but later redeems her role as sister by being especially helpful to him.

As lovers, Baldwin's women are always engaged in heterosexual affairs; lesbianism as a concept does not surface in his books. In their roles as lovers, therefore, the women are to be evaluated on the basis of how well they complement, satisfy, and work toward the happiness of the men in their lives—or, in the case of the fanatical lovers of the (masculine) Lord, the extent to which they are committed to Him. Just as mothers are to sacrifice for their children, so are women to sacrifice for their men. The women almost invariably allow the men to determine their paths in life, whether it is to be a part of the church, as with Elizabeth, or to shape her conceptions of beauty and worth, as with Tish. Julia is the only female in Baldwin's fiction who finally seems to lead a reasonably happy life without a man; when men are in her life, however, she is acutely destructive in sublimating her desires to theirs.

Lovers make up one category of romantic or sexual involvements in Baldwin's fiction, but there are others. Several women are pictured as having "loose" or questionable morals. The first of these is Esther in Go Tell It on the Mountain. Though Gabriel is basely attracted to Esther, he nevertheless tries to picture her as wanton because of the numerous young men he sees escorting her to and from work. She is outside the traditional moral values as exemplified by the members of Gabriel's church, but she is not as morally confused as Ruth in "Come Out the Wilderness." Ruth sleeps with more men than Gabriel suspects Esther of being involved with. Neither woman is presented as being emotionally stable-although Esther is certainly more men tally healthy than Ruth.

Esther and Ruth are the more "innocent" of the women with loose morals. Both Ida in Another Country and Julia in Just Above My Head are more seasoned in the liberties they take with their bodies. Ida can be described as an elevated whore; she makes a conscious decision to use her body in an effort to become a successful singer. She concludes that the only way of dealing with the exploitative system under which she must live in New York is to become the "biggest, coolest, hardest whore around."8 Julia, on the other hand, is the saint/whore, the daughter who willingly engages in incest with her father and the "sister" whose brother revels in the delights her body offers him. She is debased, but she is also a source of elevation; ultimately, she is able to extricate herself from degrading circumstances.

Few women in Baldwin's works are able to move beyond the bounds of the traditional roles that have been cut out for them and in which the use of their bodies is the most important factor. There are, nonetheless, a few iconoclasts. Florence expresses more independence than is usual with anyone in Baldwin's early fiction, and Sharon Rivers is certainly unusual in her cursing, nonreligious approach to sacrificing for her children. Ernestine, as a community activist, also moves her role beyond strict confines.

In terms of the work they do, though, few women in Baldwin's works are nontraditional. Even Florence, who values independence so much, still has a very traditional job as a domestic. Ida, in her bid to be a singer, has a profession that started in tradition and has moved beyond it. Like many women in Baldwin's works, she started out singing in the church; her desire to be a blues singer in nightclubs is the added dimension. But it is Julia who has the atypical career for women in Baldwin's fiction; she is a model. Mention of her work seems more a device for allowing Julia and Hall to meet again than to emphasize the intrinsic value of the work; but it is different from that in which most of the other women engage.

Different categories can mean that the black women are treated differently and that Baldwin has varying degrees of positive or negative responses to them. However, no woman is ultimately so acceptable to Baldwin that she is to be viewed as equal to the prominent male characters. It is a function of their guilt as well as of their creation that most of the black female characters in Baldwin's fiction have been subordinated to the males; they are in a supportive, serving position in relation to the males and the male images in their lives. They serve their neighbors; they serve their children and their husbands; and they serve God. The serving position reflects the central fact of their existence: they are incomplete without men or male images in their lives because wholeness without males is not a concept the majority of them have internalized.

Such evaluations also apply to the black women characters treated in Baldwin's dramas. Sister Margaret Alexander, pastor of the church in The Amen Corner (1954), is most like the women in the fiction in her desire and ability to serve. Though she leaves her husband, she replaces him with the church and God, and with the possibility of making her son David as unlike her husband Luke as she can. In her adherence to scripture, she is one of the most fanatical of Baldwin's black women characters. Yet in her recognition of the unrelenting antagonism between males and females, she voices the plight of all of the church-based women: "The only thing my mother should have told me is that being a woman ain't nothing but one long fight with men. And even the Lord, look like, ain't nothing but the most impossible kind of man there is."9 Juanita, in Blues for Mister Charlie (1964), asserts early upon Richard's return to their small Southern town that she views it as her responsibility to save him-from the whites as well as from himself. She determines not to let Richard "go anywhere without" her.10 At times an outspoken, feisty civil rights marcher, Juanita still experiences the most thoroughly satisfying time of her life when she is with Richard. Black women in the dramas may act differently at times because of the demands of the genre and Baldwin's political/religious statements, but in the guilt they feel and the burdens they bear, they are often strikingly akin to their novelistic sisters.

How the characters in the fiction are revealed to us is important for understanding Baldwin's progression in the treatment of them as well as for seeing more clearly the place he has assigned to them. Most of the women are revealed through omniscient narration or through male narrators in a third-person, limited point of view. The only female who narrates a story or novel is Tish in Beale Street. Like Hall Montana in Just Above My Head, she often ventures into an omni science in picturing scenes at which she is not present, in recreating conversations she has not heard, and in revealing thoughts of other characters when those thoughts have not been verbalized to her. For the male narrators, it is often necessary to consider their personalities and sympathies as well as what they present about the women characters who appear through their narrations. Black women we see in Baldwin's fiction, then, are usually at least twice removed-by way of Baldwin and his narrators-and are sometimes distanced through other layers as well.

The women presented in this study progress from trying to find sanctuary in the church to realizing that it affords none. They progress from condemning themselves for their trespasses against other human beings and against God to taking advantage whenever it is necessary and to pushing God into the background, if not completely out of their lives; community replaces church, and secular, social commitment replaces traditional religion and the hope of heaven. The women generally move out from under the shadow of their own guilt and doubt about their humanity to singing praises to life and living. Their sexual attitudes change from the pristine to the carefree and sometimes to the outrageous. They move from individual family concerns to extended and communal family concerns. Yet for all this growth and progression, for all this freedom of action and movement, the women are still confined to niches carved out for them by men whose egos are too fragile to grant their equality; and, for their own part, there are still flaws in their characters that enable them to accept those external definitions. Even the freest of Baldwin's black women, such as Ernestine in Beale Street and Julia in Just Above My Head, are initially not free of conformity, and, at some level, to male definitions of them. Finally, and most important, they are not free of the creator who continues to draw in their potential for growth on the short rein of possibility.

The many reactions I have received to my study of James Baldwin's treatment of black women in his fiction have encouraged me in my belief that such a work is necessary and timely. Individuals with whom I spoke who remembered the women in Baldwin's fiction were intrigued that I wanted to do a detailed study of these characters. Scholars more familiar with issues and themes than characters were concerned to know if the women were prominent enough to deserve a separate study and, if so, what I would say about them. Frequently persons less familiar with Baldwin's works could not remember the names of the female characters, and they often asked questions about which works were to be included in the study.

On occasion, I was surprised to discover that a writer of Baldwin's reputation evoked such vague memories from individuals in the scholarly community, most of whom maintained that they had read one or more of his fictional works. When I began a thorough examination of Baldwin scholarship, however, some of that reaction became clearer. Baldwin seems to be read at times for the sensationalism readers anticipate in his work, but his treatment in scholarly circles is not commensurate to that claim to sensationalism or to his more solidly justified literary reputation. It was discouraging, therefore, to think that one of America's best-known writers, and certainly one of its best-known black writers, has not attained a more substantial place in the scholarship on Afro-American writers. I am hopeful, therefore, that this study of the black women characters in Baldwin's fiction may inspire further discussions and promote additional detailed treatments of his works.

Within the limited number of critical volumes devoted to Baldwin, it is not surprising to discover that the female characters are the subjects of only a minute portion of them. Though Baldwin has been writing for over thirty years and has more than sixteen books to his credit, only three book-length critical studies of his work exist.1 Another book-length study is primarily biographical in orientation.2 Of these studies, none focuses exclusively on fiction, which is the genre in which Baldwin has produced most,3 and only one was published after 1978. Two collections of critical essays have been published, both before 1978.4 Only one critic distinguishes herself in the bulk of the criticism by giving more than cursory attention to the black women who populate Baldwin's fiction.5 For the other critics, these women, in spite of their roles as central or shaping forces in the lives of the male characters, have been relegated to a secondary or nonexistent place in their discussions of the fiction.

Black women such as Florence and Elizabeth in Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) have received the most critical exposure be cause parts of the novel are narrated from their points of view, but the angle of vision of the criticism has focused consistently on John and Gabriel; the women have not commanded attention in their own right as female characters. Ida, in Another Country (1962), has been judged a central character by two or three critics, but they have not followed through on their evaluations to give more than a few para graphs of commentary; she usually receives only passing attention. Women in Going to Meet the Man (1965), even Ruth, from whose point of view "Come Out the Wilderness" is narrated, have essentially been ignored. Tish (Clementine), who narrates If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), has been the subject of a couple of articles, but she has also been viewed as an unconvincing narrator. Julia and other women in Just Above My Head (1979) have been mentioned in review articles and plot summaries. Publication dates of Just Above My Head and If Beale Street Could Talk are undoubtedly relevant in considering the quantity of criticism that has appeared so far, in terms of treatment, but most of it continues the trend of giving Baldwin's black women characters only minimal attention.

The types as well as the limited number of book-length treatments of Baldwin's works underscore the fact that a major American writer has not received the intensive and extensive evaluation warranted by his prominence. While this study is designed to fill a gap in Baldwin scholarship, it has the equally important purpose of treating characters often neglected in specific discussions of Baldwin as well as in more generalized discussions of American and black American literature. Categories I define and analyses I offer about Baldwin's black female characters are derived from careful examination of Go Tell It on the Mountain, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man, If Beale Street Could Talk, and Just Above My Head.6

The black women Baldwin treats in his works play a number of roles, several of which overlap. Whatever their role, most of the women believe themselves to be guilty of some crime or condition of existence that demands their doing penance. At times the women are spiritual outcasts, psychological ghetto dwellers in a familial, sexual, religious world where their suffering does not lead to redemption. Whatever her position, no black woman in Baldwin's fiction is ultimately, continuously happy, though a few, like Julia in Just Above My Head, reach a state of contentment. Further, few of them are spiritually healthy. Their guilt for the "crimes" that they can articulate only through suffering is often tied to their evaluations of past actions in a "sinful" life. Because of their willingness to suffer, they are therefore frequently doomed to exist in psychological discomfort, in self-accusation and repression. This book examines the sources of their guilt, its manifestations in their daily lives, and the process of extrication through which the few women who do so manage to escape their guilt.

The sense of guilt the women feel is often tied to their desire to break away from roles that have been defined for them, or to their failure to fulfill a role. Almost all of the roles in which we find black women in Baldwin's fiction are traditional ones-mothers, sisters, lovers, wives-and almost all of them are roles of support for the male characters. The most prominent women we associate with Bald win's fiction are those who are solidly within the tradition of the fundamentalist church as it exists in black communities. These women may be classified as churchgoers, and appear from Go Tell It on the Mountain to Just Above My Head. The women in this cate gory come closer to being stereotypes than perhaps any others in Baldwin's works. They are usually described as large, buxom, very dark-skinned, and middle-aged or older. Their long years of faithful attendance and their tending to the souls of younger church members have won them a respectable status in the church. Usually models of Christian faith and actions to nonmembers of the church, these long suffering women are best exemplified by Praying Mother Washington and Sister McCandless in Go Tell It on the Mountain. They remind us of the matriarchal Mama Lena Younger in Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun in the unwavering quality of their faith and in their concern that other members of their immediate or church family should come into or remain within the fold of the church.

These women, like Mrs. Hunt in If Beale Street Could Talk, may be almost fanatical in the fervor with which they carry out their commitment to the church and to God. Deborah, in Go Tell It on the Mountain, clings to the church as if it is her last chance for life. Although she is younger than the other women, her life experiences have aged her prematurely, and she is therefore as "old" in faith as Praying Mother Washington. She is consistent in witnessing for the Lord, in attending to the sick and the dead, and in fervently uttering "amens" in response to Gabriel's and other preachers' sermons. These fanatical church women may on occasion make the very example of their piety a threat to those around them. People who would make fun of Deborah's plainness or of the fact that she has been raped are awed into silence by the faith she exhibits. Mrs. Hunt specifically becomes a threat to the young people around her, as do Sister Mc Candless and Sister Daniels in "The Outing." These women may also become so single-mindedly dedicated to the church that, like Mrs. Hunt, they neglect their families in a literal adaptation of the biblical injunction to sacrifice even husband, son, and daughter for one's belief in God.

A subdivision of the category of churchgoers, represented by women slightly younger than those described above, would be the one into which Elizabeth Grimes fits in Go Tell It on the Mountain. By virtue of the fact that her husband is a preacher and a deacon, Elizabeth must have a role in the church. She is torn, therefore, between what form demands and what she knows her own heart to believe. She is certainly not without faith, but she is not as believing or as committed as Deborah and Mrs. Hunt are. She tries to find the blend of raising her children within the church and minding her own soul; she does not reject one in favor of the other. She is much more silent and passive than the first category of churchgoers. Although we see her on her knees praying in church, we never hear her so much as utter an "amen" during the services she frequently attends. On rare occasions, these women in the church extend their roles beyond those of support to ones of leadership. Praying Mother Washington has a recognized position of respect in Go Tell It on the Mountain; she is "a powerful evangelist and very widely known."7 Sister Daniels, a member of the same church, has been "blessed" with a "mighty voice with which to sing and preach," and she is "going out soon into the field" (p. 57). The most prominent of the female leaders in the churches that appear in Baldwin's works, however, is Julia Miller in Just Above My Head. As a seven-year-old child prodigy preacher, she is responsible for bringing many souls to Christ.

As leaders and as supporters, the women in the church subdivide into true believers and hypocrites, which in turn affects their portrayal as women. Even among the true believers, some are presented more seriously than others; Deborah is portrayed straightforwardly, but Sister Daniels is sometimes presented in slightly derogatory ways. Mrs. Hunt is obviously a hypocrite at whom we are encouraged to laugh. How the women are presented is affected in part by the period in which the work appeared and by the nature of Baldwin's politics at the time.

Baldwin's portrayal of mothers overlaps with his portrayal of churchgoers. Indeed, many of the women in the church who have no children of their own assume the role of mother to the young people in their churches. Several of the mothers, like the churchgoing women, are long-suffering. They range from hypersensitive Elizabeth, from whom her son John must sense her moods and desires, to supportive Sharon Rivers in If Beale Street Could Talk. The atypical portrait of the mother is Mrs. Hunt, also in Beale Street, who rejects her son. The most attractive mothers are the ones who would give everything for their children, either in quiet ways, as Elizabeth does with John, or in very vocal, aggressive ways, as Sharon Rivers does with her daughter Tish. Mrs. Hunt, by contrast, is most unattractive as a mother because she fails to support, because she refuses to allow sacrifice for her family to become part of her personality.

Women as sisters are also important to Baldwin. They range from Florence in Go Tell It on the Mountain, to Ida in Another Country, to Ernestine, Adrienne and Sheila in If Beale Street Could Talk, to Julia in Just Above My Head. Sisters, like mothers, are most attractive when they are in helpful roles to other members of their families, particularly the males. Florence believes she has trouble partly because she feels she has mocked her brother Gabriel's ministry, while Ernestine is a positive image because of the sacrificial nature of her support for Tish and Fonny. Adrienne and Sheila are superficial fluffs, mere window dressing, because they care more for aristocratic manners than for their brother Fonny. Julia initially causes many problems for her younger brother Jimmy, but later redeems her role as sister by being especially helpful to him.

As lovers, Baldwin's women are always engaged in heterosexual affairs; lesbianism as a concept does not surface in his books. In their roles as lovers, therefore, the women are to be evaluated on the basis of how well they complement, satisfy, and work toward the happiness of the men in their lives—or, in the case of the fanatical lovers of the (masculine) Lord, the extent to which they are committed to Him. Just as mothers are to sacrifice for their children, so are women to sacrifice for their men. The women almost invariably allow the men to determine their paths in life, whether it is to be a part of the church, as with Elizabeth, or to shape her conceptions of beauty and worth, as with Tish. Julia is the only female in Baldwin's fiction who finally seems to lead a reasonably happy life without a man; when men are in her life, however, she is acutely destructive in sublimating her desires to theirs.

Lovers make up one category of romantic or sexual involvements in Baldwin's fiction, but there are others. Several women are pictured as having "loose" or questionable morals. The first of these is Esther in Go Tell It on the Mountain. Though Gabriel is basely attracted to Esther, he nevertheless tries to picture her as wanton because of the numerous young men he sees escorting her to and from work. She is outside the traditional moral values as exemplified by the members of Gabriel's church, but she is not as morally confused as Ruth in "Come Out the Wilderness." Ruth sleeps with more men than Gabriel suspects Esther of being involved with. Neither woman is presented as being emotionally stable-although Esther is certainly more men tally healthy than Ruth.

Esther and Ruth are the more "innocent" of the women with loose morals. Both Ida in Another Country and Julia in Just Above My Head are more seasoned in the liberties they take with their bodies. Ida can be described as an elevated whore; she makes a conscious decision to use her body in an effort to become a successful singer. She concludes that the only way of dealing with the exploitative system under which she must live in New York is to become the "biggest, coolest, hardest whore around."8 Julia, on the other hand, is the saint/whore, the daughter who willingly engages in incest with her father and the "sister" whose brother revels in the delights her body offers him. She is debased, but she is also a source of elevation; ultimately, she is able to extricate herself from degrading circumstances.

Few women in Baldwin's works are able to move beyond the bounds of the traditional roles that have been cut out for them and in which the use of their bodies is the most important factor. There are, nonetheless, a few iconoclasts. Florence expresses more independence than is usual with anyone in Baldwin's early fiction, and Sharon Rivers is certainly unusual in her cursing, nonreligious approach to sacrificing for her children. Ernestine, as a community activist, also moves her role beyond strict confines.

In terms of the work they do, though, few women in Baldwin's works are nontraditional. Even Florence, who values independence so much, still has a very traditional job as a domestic. Ida, in her bid to be a singer, has a profession that started in tradition and has moved beyond it. Like many women in Baldwin's works, she started out singing in the church; her desire to be a blues singer in nightclubs is the added dimension. But it is Julia who has the atypical career for women in Baldwin's fiction; she is a model. Mention of her work seems more a device for allowing Julia and Hall to meet again than to emphasize the intrinsic value of the work; but it is different from that in which most of the other women engage.

Different categories can mean that the black women are treated differently and that Baldwin has varying degrees of positive or negative responses to them. However, no woman is ultimately so acceptable to Baldwin that she is to be viewed as equal to the prominent male characters. It is a function of their guilt as well as of their creation that most of the black female characters in Baldwin's fiction have been subordinated to the males; they are in a supportive, serving position in relation to the males and the male images in their lives. They serve their neighbors; they serve their children and their husbands; and they serve God. The serving position reflects the central fact of their existence: they are incomplete without men or male images in their lives because wholeness without males is not a concept the majority of them have internalized.

Such evaluations also apply to the black women characters treated in Baldwin's dramas. Sister Margaret Alexander, pastor of the church in The Amen Corner (1954), is most like the women in the fiction in her desire and ability to serve. Though she leaves her husband, she replaces him with the church and God, and with the possibility of making her son David as unlike her husband Luke as she can. In her adherence to scripture, she is one of the most fanatical of Baldwin's black women characters. Yet in her recognition of the unrelenting antagonism between males and females, she voices the plight of all of the church-based women: "The only thing my mother should have told me is that being a woman ain't nothing but one long fight with men. And even the Lord, look like, ain't nothing but the most impossible kind of man there is."9 Juanita, in Blues for Mister Charlie (1964), asserts early upon Richard's return to their small Southern town that she views it as her responsibility to save him-from the whites as well as from himself. She determines not to let Richard "go anywhere without" her.10 At times an outspoken, feisty civil rights marcher, Juanita still experiences the most thoroughly satisfying time of her life when she is with Richard. Black women in the dramas may act differently at times because of the demands of the genre and Baldwin's political/religious statements, but in the guilt they feel and the burdens they bear, they are often strikingly akin to their novelistic sisters.

How the characters in the fiction are revealed to us is important for understanding Baldwin's progression in the treatment of them as well as for seeing more clearly the place he has assigned to them. Most of the women are revealed through omniscient narration or through male narrators in a third-person, limited point of view. The only female who narrates a story or novel is Tish in Beale Street. Like Hall Montana in Just Above My Head, she often ventures into an omni science in picturing scenes at which she is not present, in recreating conversations she has not heard, and in revealing thoughts of other characters when those thoughts have not been verbalized to her. For the male narrators, it is often necessary to consider their personalities and sympathies as well as what they present about the women characters who appear through their narrations. Black women we see in Baldwin's fiction, then, are usually at least twice removed-by way of Baldwin and his narrators-and are sometimes distanced through other layers as well.

The women presented in this study progress from trying to find sanctuary in the church to realizing that it affords none. They progress from condemning themselves for their trespasses against other human beings and against God to taking advantage whenever it is necessary and to pushing God into the background, if not completely out of their lives; community replaces church, and secular, social commitment replaces traditional religion and the hope of heaven. The women generally move out from under the shadow of their own guilt and doubt about their humanity to singing praises to life and living. Their sexual attitudes change from the pristine to the carefree and sometimes to the outrageous. They move from individual family concerns to extended and communal family concerns. Yet for all this growth and progression, for all this freedom of action and movement, the women are still confined to niches carved out for them by men whose egos are too fragile to grant their equality; and, for their own part, there are still flaws in their characters that enable them to accept those external definitions. Even the freest of Baldwin's black women, such as Ernestine in Beale Street and Julia in Just Above My Head, are initially not free of conformity, and, at some level, to male definitions of them. Finally, and most important, they are not free of the creator who continues to draw in their potential for growth on the short rein of possibility.

Recenzii

"Harris breaks new ground with this book. Cross-gender representations have been a problem for black writers and critics for some time, but no one before has systematically examined a writer's body of work to explore the topic. . . . the book is thorough and useful, and sets a model for further cross-gender explorations of black writers."