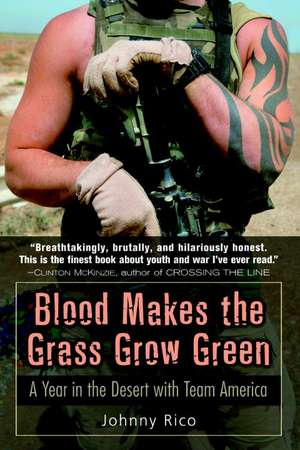

Blood Makes the Grass Grow Green: A Year in the Desert with Team America

Autor Johnny Ricoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2007

No one would have picked Johnny Rico for a soldier. The son of an aging hippie father, Johnny was overeducated and hostile to all authority. But when 9/11 happened, the twenty-six-year-old probation officer dropped everything to become an “infantry combat killer.”

But if he’d thought that serving his country would be the kind of authentic experience a reader of The Catcher in the Rye would love, he quickly realized he had another thing coming. In Afghanistan he found himself living a Lord of the Flies existence among soldiers who feared civilian life more than they feared the Taliban–guys like Private Cox, a musical prodigy busy “planning his future poverty,” and Private Mulbeck, who didn’t know precisely which country he was in. Life in a combat zone meant carnage and courage–but it also meant tedious hours standing guard, punctuated with thoughtful arguments about whether Bea Arthur was still alive.

Utterly uncensored and full of dark wit, Blood Makes the Grass Grow Green is a poignant, frightening, and heartfelt view of life in this and every man’s army.

Preț: 114.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.89€ • 22.61$ • 18.22£

21.89€ • 22.61$ • 18.22£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780891418979

ISBN-10: 0891418970

Pagini: 318

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE INSERT

Dimensiuni: 140 x 209 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0891418970

Pagini: 318

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE INSERT

Dimensiuni: 140 x 209 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Extras

Chapter 1 Night Patrol: Dancing with Cornflakes in Afghanistan

I was somewhere in the desert at the edge of civilization when the psychosis began to take hold. My heart beats securely and steadily, buried deep somewhere in this gear I wear. It’s buried by bulletproof plates and flack vests and tactical vests and ammunition and global positioning system handheld devices and maps and red star cluster flares and grenades and canteens and cigarettes and gum and Jolly Ranchers, but my heart is in there somewhere. I can feel it thumping securely somewhere deep inside. I feel encased, entombed in a catalog of military waste. My hands, sheathed in thin trigger-ready gloves, feel like distant attachments, moving inexplicably without my knowledge as they crinkle and fist and smooth themselves in nervous fidgety tics. Something’s cutting into my hip. Some buried harness or piece of equipment isn’t fitting well. Something is always sitting wrong. You reorganize, readjust, refit, and go back out, and something’s always cutting you, biting you. My green night vision goggles with their scratched exterior lens make me think that the scratch is out there beyond my Humvee all-terrain vehicle flying through the open desert. I’m always wondering what’s beside that building or on the side of the mountain, and I have to always remind myself seconds later that it’s only my scratch. My little lens scratch. I can’t get foreground and background to come into focus simultaneously. I keep rotating my focus lever until I get tired and just leave everything blurry. It’s like playing with rabbit ears on an old decrepit television; you can’t get good reception no matter how much you mess with it. My night vision goggles keep slipping. I need a new mount. Mounts are hard to come by. Some guys had been waiting for mounts before we left for this deployment. The mounts had supposedly been “on order” for the last six months. I should’ve just gone on line and bought a new mount myself from a private company, and then I’d have had mine in six weeks like everyone else. It was the principle of the thing, though. I didn’t want to buy any more of my own gear. I’ve already spent thousands outfitting myself for the war, and I refuse to spend one dollar more. So I sit here instead, one eye shut and one eye open, behind a green lens that’s increasingly slipping, cutting the vision in my one good eye in half. I focus on the weird light patterns that you get when you close your eyes after staring into a lightbulb and watch them float around this black vacuum like fluorescent ghosts that drift quietly in a luminescent world. The form of the residual light is what I can only describe as cornflakes. Relaxed, slowly drifting cornflakes. In my mind’s eye I am zooming in to join them, dancing with them and floating. Just dancing with the cornflakes in Afghanistan. I feel relaxed. Is this meditation? Just sitting here floating and dancing with the phantoms of residual light that remind me of cornflakes? The radio crackles next to my ear. I am suddenly brought back to the mission. To reality. We’re in the Humvee. I can’t understand what he said. He said something that sounded like “. . . on the hill; over?” Was that a question? Is he asking me a question or giving me a command? Should I call him back? No, I won’t, I decide. He’ll call back if it’s important. We pull to a stop, and I look sideways out my window. I see two red lights of some vehicles way off in the distance on a mountain across the valley. They’re moving. My vision shifts. And then I notice they aren’t distant vehicles. They’re the taillights of the other Humvee. The one only five feet from my own. I shake my head. I have to get straight in the head. Stupid night vision—there’s no depth perception, no peripheral vision, no detailed texture that allows for easily identifiable scale or size comparison. My vehicle moves forward as I struggle lamely against the piles of ammunition on my right side between me and the legs of our gunner, who’s popped up through the roof manning the .50-caliber machine gun mounted on top. To my left is the metal door. My legs—damn, my long fucking legs are awkwardly bent and pressed intensely into the metal frame of the seat in front of me. I am surrounded by metal. I hate metal. It’s so cold and unforgiving and sterile and harsh. I wish I could surrounded myself with sock monkeys. Soft sock monkeys. My grandma used to make me sock monkeys, monkeys made out of used socks. They were not only soft but strangely comforting and safe, despite rather grotesque grimaces perpetually framed on their faces. Those monkey faces were the type of faces I imagine child molesters get when they spy their prey: big wide eyes and extreme exaggerated creepy pedophile smiles. Maybe I don’t want to be surrounded by sock monkeys, but perhaps a towel, a nice soft towel or a bathrobe, the kind I used as a blanket when I’d curl up on the heating vent with the family cat when I was just a little boy. Me and the cat underneath a towel. That’d be nice. I rip off my helmet and breathe deeply, sucking air and choking on it as if I’d just emerged from a pool and a long swim underwater. Am I the only one who gets claustrophobic just wearing my gear? I want to rip it all off and run around the Humvee naked, flapping my arms and immersing myself in the cold air of early winter while yelping like a bird. Yes, the bird yelping would be a nice touch. I’d surely get discharged for that. Psychological discharge. Why the psychological discharge? “Well, sir, he was yelping like a bird and running around naked while on a mission.” Anything to get me out. I can’t afford to stay in. They’re saying I’m going be stop-lossed. “Stop loss” means you can’t get out of the Army. That means the Army lets you go when they want to let you go. Just hearing the words makes me sick to my stomach. Sudden sickness as an electrical charge rips through my intestines and I feel my bowels loosen and lose their solid form. My stomach acid churns on itself. My head pounds. My breathing rises. I have so much to do, so many plans, so many timetables and life schedules to meet. My old professor is leaving, moving to Philadelphia. I have to start doing research with him, make up for all the time I lost in the Army being inactive in academia. He’s my ticket to graduate school and my doctorate. My best friend, Sean, is teaching at Metro State as a part-time professor, and I want to do that too. But time, my time, is slipping. The more years that separate me from academia, the harder it will be to get hired. Sean and Eric and Elizabeth’s dad and I are all supposed to climb Kilimanjaro in Kenya in the spring of 2006. They’re all carefully planning and manipulating to get time off. My sister has secured a job for me in Antarctica for the fall of 2005, and if that doesn’t work my ex-employer keeps talking about holding my old job for me. But how many years can I expect to hear this offer, which comes every year with a little less frequency? And I’ll miss out on all of it, sitting at some lonely Army base two years after the date I was supposed to get out of the Army, finding that all my plans have passed me by because the Army had to keep me past my normal enlistment term to go to Iraq. I’m going to miss out on my life. I feel sad about my supposedly intentionally noble decision to join the Army and serve and protect my country after September 11 and to take a three-year break from my career. It seems to be turning into a disastrous move. I hate to feel this way—that serving my country will have been the worst mistake of my life—but if I get kept an additional two years beyond when I was supposed to have been let go, it will have become exactly that. I don’t want to regret serving America. But with all the hard work I put into creating a career, crafting my little niche in the world, and obtaining an education, I can’t afford to take a five-year detour. The only lesson to be learned is to not make the mistake and give them a few years because they’ll take from you as many as they want. This is my advice to the youth of America: Don’t serve. You’ll regret it if you have anything else you want to do with your life. And that three-year contract you’re going to sign? Read the fine print; they can keep you as long as they want. We pull to a stop. We’re on a cold windy ridge studded with ragged poles, with flags and pennants waving off of them. My intuitively deductive mind figures out that it’s some type of Haji marking system. “What’s this?” Cox asks. “Some type of Haji marking system,” I cleverly remark. I sit down Indian style on a smooth face of rock and stare off into the darkness for some seriously intense observation. Below the ridge is nothing but darkness. I might as well be staring out into the voids of space beyond the galaxies where there are no stars. I get the sudden feeling that I’m sitting on the edge of an abyss that leads to a free fall of never-ending darkness. No. Wait. Scratch that abyss comment. I see some wheatfields down there, or something. Never mind. Everybody’s quiet. There is some brief scatter of conversation, which is quickly muted. It’s too cold to be talkative, and besides, it’s no fun talking in hushed whispers. I scan my sector, but my thoughts keep drifting. I wonder exactly how big Amanda’s breasts are. They seemed so perky and sizable, yet the last time I went to feel them under the pretense of innocent cuddling, I quickly realized she had on a Wonderbra. I think about the movies I want to play during my shift as radio guard tomorrow. I think it’s time for a rotation of the classics. Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, maybe The Maltese Falcon. I bet Amanda has big nipples. Big pink nipples. I haven’t seen them, of course, but I’ve felt them sliding in and out of my fingertips. I’m not paying attention. I have to pay attention, scan my sector, soldier-the-fuck-onward. I have to shake this extraneous thought, get back to the mission at hand. I have to pay attention, stay sharp, stay frosty. I wonder if Amanda likes having her nipples sucked? This is how it’s done. We move to invisible over watch positions in the middle of the night for patrols. No one is aware of our presence in small concentric circles outside our firebase. Most of Afghanistan is in chaos, under the control of thugs and warlords. But for a two-kilometer radius around Firebase Dizzy, we are in control. And we control this two-kilometer radius with a vivacious indifference and mediocrity. That’s the level of commitment and dedication and sacrifice I’m talking about. Later, back at base, the soldiers drop from the Humvees and jump off roofs and dismount as orange-cherry tips of cigarettes break the blank lightless vacuum of the night. We’re at a tiny Special Forces compound separated from our parent Cougar (Charlie) company chain of command, providing security so the Special Forces can do missions without having to worry about their base. It’s a choice position that we’re all happy to have, because simply by working in a Special Forces base, we get three hot meals a day, and soda, and Internet and phone access to contact our loved ones back home, even though we’re somewhere in central Afghanistan about a day’s drive from any other U.S. forces deep behind enemy lines in Taliban country. In the adobe operations building with its secret hallways and back rooms, my gear falls off in random clumps and piles around the floor. The operations building is a complete mess, with empty Kool-Aid mix cans and candy wrappers littering the floor. Mulbeck, my nighttime counterpart in the perpetual task of radio guard, and two other soldiers are inside in T-shirts and socks, laughing at the movie Old School playing on the television. I enter the walk-in supply closet and offer a secret meal of milk and tuna to Brian, the kitten I adopted when we first arrived. Underweight and pitiful, he had been close to death. But I nursed him back to health and put a little meat on his slender kitten frame. Specialist Walker, our medic, used a laser to remove a growth from his eye, and he is now a happy plucky kitten, who perpetually pours forth affection toward those of us who saved him. I pull him from the rain tarp I’d buried him in and laugh at his confused sleepy-eyed bewilderment and feed him as I gently stroke his little head. When I finger the black patch of fur over his eye, he droops his head and purrs. Hiding Brian in my shirt, I go outside and climb onto the roof of the operations building, where I keep an extra cot. The rooftop is a tangled mess of wire and electrical cords running in every direction, the result of years of quick fixes by whoever happened to have the slightest bit of electrical know-how. Every day our power goes out for an hour or two, and each quick fix only compounds the problem of split wires and jerry-rigged transformers. Various antennas for radio systems point up at odd angles, unstable, rigged with duct tape, leaning too far one way or another. I do a perfunctory search of my cot and the immediate rooftop for the tarantula-sized leaping and biting sand spiders, and then snuggle deep into my sleeping bag. The cool desert air engulfs my body and causes light goose bumps to rise up underneath the desert camouflage uniform that I’ve been wearing for over a week. When you only own three sets of clothes, you stop caring about changing them. I rest my hands behind my head and stare up at the stars as I turn on my iPod to listen to the Beatles as I pet Brian. You can actually see the stars. Not just the stars, but the milky dust of the cosmos, a hazy twilight mist floating in a vacuum that somehow seems to accentuate the smallness of everything under it. A blitzkrieg of brilliant points of light breaking the blackness of empty space with fierce determination. With the power grids and neon and fluorescent noises turned off, the stars are so bright you can taste them.

I was somewhere in the desert at the edge of civilization when the psychosis began to take hold. My heart beats securely and steadily, buried deep somewhere in this gear I wear. It’s buried by bulletproof plates and flack vests and tactical vests and ammunition and global positioning system handheld devices and maps and red star cluster flares and grenades and canteens and cigarettes and gum and Jolly Ranchers, but my heart is in there somewhere. I can feel it thumping securely somewhere deep inside. I feel encased, entombed in a catalog of military waste. My hands, sheathed in thin trigger-ready gloves, feel like distant attachments, moving inexplicably without my knowledge as they crinkle and fist and smooth themselves in nervous fidgety tics. Something’s cutting into my hip. Some buried harness or piece of equipment isn’t fitting well. Something is always sitting wrong. You reorganize, readjust, refit, and go back out, and something’s always cutting you, biting you. My green night vision goggles with their scratched exterior lens make me think that the scratch is out there beyond my Humvee all-terrain vehicle flying through the open desert. I’m always wondering what’s beside that building or on the side of the mountain, and I have to always remind myself seconds later that it’s only my scratch. My little lens scratch. I can’t get foreground and background to come into focus simultaneously. I keep rotating my focus lever until I get tired and just leave everything blurry. It’s like playing with rabbit ears on an old decrepit television; you can’t get good reception no matter how much you mess with it. My night vision goggles keep slipping. I need a new mount. Mounts are hard to come by. Some guys had been waiting for mounts before we left for this deployment. The mounts had supposedly been “on order” for the last six months. I should’ve just gone on line and bought a new mount myself from a private company, and then I’d have had mine in six weeks like everyone else. It was the principle of the thing, though. I didn’t want to buy any more of my own gear. I’ve already spent thousands outfitting myself for the war, and I refuse to spend one dollar more. So I sit here instead, one eye shut and one eye open, behind a green lens that’s increasingly slipping, cutting the vision in my one good eye in half. I focus on the weird light patterns that you get when you close your eyes after staring into a lightbulb and watch them float around this black vacuum like fluorescent ghosts that drift quietly in a luminescent world. The form of the residual light is what I can only describe as cornflakes. Relaxed, slowly drifting cornflakes. In my mind’s eye I am zooming in to join them, dancing with them and floating. Just dancing with the cornflakes in Afghanistan. I feel relaxed. Is this meditation? Just sitting here floating and dancing with the phantoms of residual light that remind me of cornflakes? The radio crackles next to my ear. I am suddenly brought back to the mission. To reality. We’re in the Humvee. I can’t understand what he said. He said something that sounded like “. . . on the hill; over?” Was that a question? Is he asking me a question or giving me a command? Should I call him back? No, I won’t, I decide. He’ll call back if it’s important. We pull to a stop, and I look sideways out my window. I see two red lights of some vehicles way off in the distance on a mountain across the valley. They’re moving. My vision shifts. And then I notice they aren’t distant vehicles. They’re the taillights of the other Humvee. The one only five feet from my own. I shake my head. I have to get straight in the head. Stupid night vision—there’s no depth perception, no peripheral vision, no detailed texture that allows for easily identifiable scale or size comparison. My vehicle moves forward as I struggle lamely against the piles of ammunition on my right side between me and the legs of our gunner, who’s popped up through the roof manning the .50-caliber machine gun mounted on top. To my left is the metal door. My legs—damn, my long fucking legs are awkwardly bent and pressed intensely into the metal frame of the seat in front of me. I am surrounded by metal. I hate metal. It’s so cold and unforgiving and sterile and harsh. I wish I could surrounded myself with sock monkeys. Soft sock monkeys. My grandma used to make me sock monkeys, monkeys made out of used socks. They were not only soft but strangely comforting and safe, despite rather grotesque grimaces perpetually framed on their faces. Those monkey faces were the type of faces I imagine child molesters get when they spy their prey: big wide eyes and extreme exaggerated creepy pedophile smiles. Maybe I don’t want to be surrounded by sock monkeys, but perhaps a towel, a nice soft towel or a bathrobe, the kind I used as a blanket when I’d curl up on the heating vent with the family cat when I was just a little boy. Me and the cat underneath a towel. That’d be nice. I rip off my helmet and breathe deeply, sucking air and choking on it as if I’d just emerged from a pool and a long swim underwater. Am I the only one who gets claustrophobic just wearing my gear? I want to rip it all off and run around the Humvee naked, flapping my arms and immersing myself in the cold air of early winter while yelping like a bird. Yes, the bird yelping would be a nice touch. I’d surely get discharged for that. Psychological discharge. Why the psychological discharge? “Well, sir, he was yelping like a bird and running around naked while on a mission.” Anything to get me out. I can’t afford to stay in. They’re saying I’m going be stop-lossed. “Stop loss” means you can’t get out of the Army. That means the Army lets you go when they want to let you go. Just hearing the words makes me sick to my stomach. Sudden sickness as an electrical charge rips through my intestines and I feel my bowels loosen and lose their solid form. My stomach acid churns on itself. My head pounds. My breathing rises. I have so much to do, so many plans, so many timetables and life schedules to meet. My old professor is leaving, moving to Philadelphia. I have to start doing research with him, make up for all the time I lost in the Army being inactive in academia. He’s my ticket to graduate school and my doctorate. My best friend, Sean, is teaching at Metro State as a part-time professor, and I want to do that too. But time, my time, is slipping. The more years that separate me from academia, the harder it will be to get hired. Sean and Eric and Elizabeth’s dad and I are all supposed to climb Kilimanjaro in Kenya in the spring of 2006. They’re all carefully planning and manipulating to get time off. My sister has secured a job for me in Antarctica for the fall of 2005, and if that doesn’t work my ex-employer keeps talking about holding my old job for me. But how many years can I expect to hear this offer, which comes every year with a little less frequency? And I’ll miss out on all of it, sitting at some lonely Army base two years after the date I was supposed to get out of the Army, finding that all my plans have passed me by because the Army had to keep me past my normal enlistment term to go to Iraq. I’m going to miss out on my life. I feel sad about my supposedly intentionally noble decision to join the Army and serve and protect my country after September 11 and to take a three-year break from my career. It seems to be turning into a disastrous move. I hate to feel this way—that serving my country will have been the worst mistake of my life—but if I get kept an additional two years beyond when I was supposed to have been let go, it will have become exactly that. I don’t want to regret serving America. But with all the hard work I put into creating a career, crafting my little niche in the world, and obtaining an education, I can’t afford to take a five-year detour. The only lesson to be learned is to not make the mistake and give them a few years because they’ll take from you as many as they want. This is my advice to the youth of America: Don’t serve. You’ll regret it if you have anything else you want to do with your life. And that three-year contract you’re going to sign? Read the fine print; they can keep you as long as they want. We pull to a stop. We’re on a cold windy ridge studded with ragged poles, with flags and pennants waving off of them. My intuitively deductive mind figures out that it’s some type of Haji marking system. “What’s this?” Cox asks. “Some type of Haji marking system,” I cleverly remark. I sit down Indian style on a smooth face of rock and stare off into the darkness for some seriously intense observation. Below the ridge is nothing but darkness. I might as well be staring out into the voids of space beyond the galaxies where there are no stars. I get the sudden feeling that I’m sitting on the edge of an abyss that leads to a free fall of never-ending darkness. No. Wait. Scratch that abyss comment. I see some wheatfields down there, or something. Never mind. Everybody’s quiet. There is some brief scatter of conversation, which is quickly muted. It’s too cold to be talkative, and besides, it’s no fun talking in hushed whispers. I scan my sector, but my thoughts keep drifting. I wonder exactly how big Amanda’s breasts are. They seemed so perky and sizable, yet the last time I went to feel them under the pretense of innocent cuddling, I quickly realized she had on a Wonderbra. I think about the movies I want to play during my shift as radio guard tomorrow. I think it’s time for a rotation of the classics. Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, maybe The Maltese Falcon. I bet Amanda has big nipples. Big pink nipples. I haven’t seen them, of course, but I’ve felt them sliding in and out of my fingertips. I’m not paying attention. I have to pay attention, scan my sector, soldier-the-fuck-onward. I have to shake this extraneous thought, get back to the mission at hand. I have to pay attention, stay sharp, stay frosty. I wonder if Amanda likes having her nipples sucked? This is how it’s done. We move to invisible over watch positions in the middle of the night for patrols. No one is aware of our presence in small concentric circles outside our firebase. Most of Afghanistan is in chaos, under the control of thugs and warlords. But for a two-kilometer radius around Firebase Dizzy, we are in control. And we control this two-kilometer radius with a vivacious indifference and mediocrity. That’s the level of commitment and dedication and sacrifice I’m talking about. Later, back at base, the soldiers drop from the Humvees and jump off roofs and dismount as orange-cherry tips of cigarettes break the blank lightless vacuum of the night. We’re at a tiny Special Forces compound separated from our parent Cougar (Charlie) company chain of command, providing security so the Special Forces can do missions without having to worry about their base. It’s a choice position that we’re all happy to have, because simply by working in a Special Forces base, we get three hot meals a day, and soda, and Internet and phone access to contact our loved ones back home, even though we’re somewhere in central Afghanistan about a day’s drive from any other U.S. forces deep behind enemy lines in Taliban country. In the adobe operations building with its secret hallways and back rooms, my gear falls off in random clumps and piles around the floor. The operations building is a complete mess, with empty Kool-Aid mix cans and candy wrappers littering the floor. Mulbeck, my nighttime counterpart in the perpetual task of radio guard, and two other soldiers are inside in T-shirts and socks, laughing at the movie Old School playing on the television. I enter the walk-in supply closet and offer a secret meal of milk and tuna to Brian, the kitten I adopted when we first arrived. Underweight and pitiful, he had been close to death. But I nursed him back to health and put a little meat on his slender kitten frame. Specialist Walker, our medic, used a laser to remove a growth from his eye, and he is now a happy plucky kitten, who perpetually pours forth affection toward those of us who saved him. I pull him from the rain tarp I’d buried him in and laugh at his confused sleepy-eyed bewilderment and feed him as I gently stroke his little head. When I finger the black patch of fur over his eye, he droops his head and purrs. Hiding Brian in my shirt, I go outside and climb onto the roof of the operations building, where I keep an extra cot. The rooftop is a tangled mess of wire and electrical cords running in every direction, the result of years of quick fixes by whoever happened to have the slightest bit of electrical know-how. Every day our power goes out for an hour or two, and each quick fix only compounds the problem of split wires and jerry-rigged transformers. Various antennas for radio systems point up at odd angles, unstable, rigged with duct tape, leaning too far one way or another. I do a perfunctory search of my cot and the immediate rooftop for the tarantula-sized leaping and biting sand spiders, and then snuggle deep into my sleeping bag. The cool desert air engulfs my body and causes light goose bumps to rise up underneath the desert camouflage uniform that I’ve been wearing for over a week. When you only own three sets of clothes, you stop caring about changing them. I rest my hands behind my head and stare up at the stars as I turn on my iPod to listen to the Beatles as I pet Brian. You can actually see the stars. Not just the stars, but the milky dust of the cosmos, a hazy twilight mist floating in a vacuum that somehow seems to accentuate the smallness of everything under it. A blitzkrieg of brilliant points of light breaking the blackness of empty space with fierce determination. With the power grids and neon and fluorescent noises turned off, the stars are so bright you can taste them.

Notă biografică

Johnny Rico graduated from the University of Colorado in 2001. A month after September 11, 2001, he joined the Army under the delayed entry program. He was sent to Afghanistan with C. Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Infantry, of the 25th Infantry (Light) Division in Hawaii, where he served as an infantryman in three different areas of operation. He was released from active duty in September 2005.

Descriere

In this fresh and funny Afghanistan War memoir, a highly liberal, highly educated army misfit chronicles his time in the war with a healthy dose of skepticism and razor sharp wit.