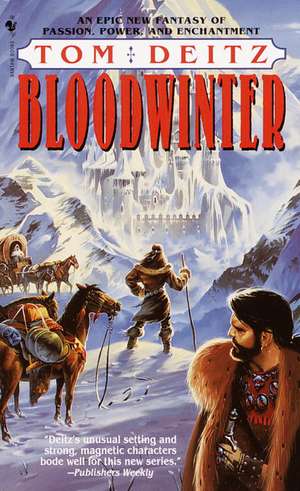

Bloodwinter

Autor Tom Deitzen Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 apr 2000

From a master of contemporary fantasy comes an unforgettable tale of heroes, heroines, and rogues whose two rival nations are scarred by suspicion, shadowed by war, and summoned to destiny by a magic that is both gift and curse.

In the icy northern realm of Eron, three young artisans bound by an unspeakable act of violence arrive at an isolated gem mine on a special commission for their king. They are the arrogant but talented Eddyn; Avall, his archrival; and beautiful Strynn, newly wed to Avall, but carrying Eddyn's child.

Meanwhile, to the south, amid Ixti's scorpion-riddled sands and sensuous cities, a horrible accident has forced Prince Kraxxi into exile with blood on his hands and a price on his head.

The four will be drawn together--and torn apart--by a magnificent find: a gem with magical properties beyond anyone's imagining or control. It is a struggle in which hidden forces pursue a frighteningly sinister agenda. For whoever possesses the gem holds the future of the world...and the power to destroy it.

Preț: 56.99 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 85

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.91€ • 11.25$ • 9.10£

10.91€ • 11.25$ • 9.10£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553576467

ISBN-10: 0553576461

Pagini: 608

Dimensiuni: 105 x 174 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

ISBN-10: 0553576461

Pagini: 608

Dimensiuni: 105 x 174 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Extras

Spring, Amalian concluded, had arrived not an instant too early.

It had snowed as late as yester morn: thick, heavy flakes that had come wafting out of the northwest, as though the mountains in Angen's Spine were airing out their linens for the Light. Which, she supposed, made her and the trek she mastered among the larger, more recalcitrant motes of accumulated detritus. If The Eight dwelt in those gloomy peaks behind her, which she doubted--or if the rocks themselves were subtly alive, which some of Common Clan averred--they'd have to rise early indeed to loathe the cold season as much as she.

Oh, it had been beautiful enough in Stone-Hold-Winter, where the Fateing had sent her last Dark Half. The head-high drifts had made a fabulous backdrop for the statuary in the forecourt: warriors this rotation, carved in ruddy catlinite that contrasted nicely with the dark green hollies. Still, the cliffs and crags so prevalent thereabouts were harsh, naked rock that had as its primary virtue its many grades and colors, most of which were good for carving--which Amalian had spent all winter doing, and which was another thing she wouldn't miss with the turning of the year.

At least she hadn't been cold. Some of the winter holds were absolutely frigid, in spite of the steam-springs with which they were heated. Besides, Gory had been posted with her, and he was furry enough to keep several people warm--even through those wild solstice storms when three strong sets of walls and doors between living quarters and the cold without failed to stave off winter's fingers.

But she'd missed people, curse it! People in all their variety--any people beyond the same double-hundred-odd she'd seen day in and day out at the hold. And over half of those were her kin, whom she saw most of the year anyway.

Which was why, when Stone-Hold's weather-witch predicted an early spring and the Ekkon River broke through its ice a whole eight-day sooner than expected, she'd determined to take the risk.

So far it had been worth it, with far more color in the first-blooms than usual. Why, the gold stars that named this place almost glowed, and the ferns and bracken were particularly bright and frothy in the hollows among the pines. And the skies! Clear for days (yester morn notwithstanding) and so blue she wanted to reach up and chip away a chunk to carve into something precious.

Something for the twins, perhaps. Carmil and Egin: girl and boy. Thirteen now, and poised on the chisel blade between the children they'd been last Sundeath, when the journey north had begun, and the adults they were fast becoming. Both were a hand taller than when they'd left the lowlands, and Carmil had breasts and a woman's bleeding. Egin's voice was shifting so that his singing, which had been so sweet, was now rather more like croaking. And Gory, who'd seen him daily in the baths, had confided that their little boy now had hair in all men's places--matching that on his head, which was the same red-lit black as his sire's. Carmil's mirrored Amalian's own rare tawny gold.

She wondered where they were now. Riding ahead with Gory, perhaps? Or back swapping tales with the braver folk from Oak, who'd swelled their ranks that morning? She envied them--the children their freedom, the Oak folk their proximity to the northmost of the gorges where the bulk of clan, craft, and kin spent Eron's too-brief summers. It was to that cleft in the coastal plateau that Amalian led the trek now, through melting drifts of knee-deep snow. If luck rode with them, some of them would sleep in their own beds tonight, which would be change enough from the crowded chaos of the way stations that marked the nights between holds, halls, and gorges.

Sighing, she reached back to flip up her cloak's fur-lined hood. A breeze had come whipping out of the gap ahead, and she wondered if the twinge troubling her knees as she resettled them was merely token of a winter's inaction or the first insidious gnawings of old age.

Not the latter, she prayed. She wasn't far past thirty, and the sixty more years she expected to attain would be no great joy if her joints chose to ache through most of them.

And then the wind shifted, riding in from the south, bringing with it a hint of warmth that stirred her heart out of all proportion to its intensity.

But it brought other things as well: the scent of death, and, so faint as to be barely discernible, the scent of burning.

* * *

"I smell death," Amalian informed her husband, reining back the team: golds from Arsten, which had been part of her wedding dower from Gory's clan, who bred them.

Gory slapped his fractious gray gelding and nodded, his breath making blizzards in the air, riming the beard that framed his narrow, blue-eyed face. His cloak twitched in the wind. "Sheep," he grunted, as though that explained everything.

Amalian raised a brow. Gory was a fine man and an excellent mate--and said about ten words an eighth, as though he'd been born with a fixed allotment and treasured them like his clan treasured wagon-cattle.

"Which I presume belong to somebody," Amalian sighed, thinking that perhaps she might get a better account from the spindly pines that flanked the road to the left, or the rough-shelved slate cliffs slanting up to the right.

Gory grimaced. "Haven't been dead long, and there's only two. Margil's spent some time with the sheep folk and says the clan clips on their ears mark them as belonging to a small sept-hall on the south rim of North Gorge."

"A good day's ride from here."

Gory nodded.

"Wolves, then? Or birkits? Or--" She refused to name the other, because there was supposed to be no other. Wisdom said it was too cold for geens--man-sized lizard-things that walked on their hind legs--north of South Gorge. But Amalian wondered. Wisdom also said they were stupid as snakes, and she knew that was a lie.

Gory shrugged. "Just dead. A little rotten, no sign of violence."

"How long?"

Another shrug. "Thawed maybe two days. Beyond that, the only way of knowing is if we had a female, to check the unborn. They tend to conceive close to the same time."

"Lucky for us--if we had one," Amalian snorted. "Still, livestock escapes. And escaped livestock often dies."

"Aye," was Gory's sole reply.

* * *

By midday they'd crested Gold Star Gap and were on the last long winding slope before the road poured them out on the plains southeast below them: a patchwork of waving sheep grass and lingering snow, framed by the tips of the flanking pines. By midafternoon North Gorge should be in sight. By sunfall, they should be well on their way to Tir-Mil at the bottom.

But somehow she was uneasy. Not one person in the hundred had offered anything useful about the dead sheep, and they'd seen fifteen now. Speculation over them had been curtailed when they'd found the dead man.

It had been Gory (again) who'd discovered him--poor Gory, whose draw it had been to lead the day's outriders. The man had been dead at least eight days, and scavengers had been at him, so that it was hard to tell much save that he'd sheltered at Sharp Stone Station to bathe in the waters there and succumbed--naked--on the deep pool's stony marge. Heart freeze was possible. Heat could do that, and it was a very hot spring (and one Amalian had looked forward to sampling before their final approach). As best they could tell, the man had been in his early twenties. And, by the clothing flung about and ravaged--likely by the same beasts that had gnawed away his insides--he'd come from a prosperous clan. Beyond that, he'd been unremarkable. Black-haired, lightly bearded, fairly hairy, fit, and of the middle height and slim build typical of the Eronese. His clan tattoo, which would have revealed much, had been devoured along with most of his shoulder. Or scratched away, for the bulk of the man's intact skin was covered with long, deep furrows. He'd hacked off his hair, too, and not neatly, though men often did that near the end of the Dark.

It was another mystery. Amalian had ordered his body wrapped in oiled canvas and stored in the rearmost wagon. Burning would come later, when they'd determined his identity.

* * *

Four sun-hands later, they'd found a dozen more sheep, dead exactly as the others, but clipped to a different clan. And while that disturbed Amalian, it didn't truly concern her. By nightfall they'd be in Tir-Mil, where'd there'd be people whose duty it was to attend such things. She was merely the messenger.

What did disturb her was the fact that they could see the gorge now: a dark slash on the horizon, with the perpetual veil of steam rising out of it. But that steam was laced with darker vapors, which could only be the smoke of copious burning.

She smelled it, too, as she had that morning. But now it held a sharp, sweet tang she didn't like. If she didn't know better--if such things hadn't been rendered impossible by unshakable oaths between clan and craft--she'd have sworn war ravaged the gorge.

But that was absurd.

Besides, the road was flattening, the pines falling away to either side, and there was more waving grass ahead than melting snow, and that made her heart sing and fly.

The children sang as well--when they deigned to ride beside her: Carmil in her usual clear soprano, Egin in a cracky, pretentious boy-bass. It was a new song, too, one someone at Oak had contrived over the Deep, and seemed to involve a drunken man trying to sleep with women who were not always women. So much for her children's innocence. Egin fairly glowed. She wondered if that spotty glitter along his jaw was the first outpost of stubble.

Three hands later, they crested a rise and saw the guard station sprawling across the road ahead, maybe a shot from the gorge's northeast rim. Like most such structures built in High King Kryss's time, it was utterly unadorned and of the prescribed configuration: a single square tower five levels high, with smooth, trapezoidal sides and a flat roof. Each side fronted a square, walled courtyard marked by a two-story gatehouse, and the whole complex was enclosed by a lower wall to form a square within a cross within a square when viewed from above. The walls were thick, the stonework set with such impeccable skill as to show only hair-fine joins, so that neither foe nor winter could claim a hold. With shots of open country around, the former was unlikely; the latter a foregone conclusion.

Usually, though, such places were alive with people going about their tasks like ants upon a hill. And while Amalian knew that she'd come upon them days before expected, that offered no explanation for the air of decrepitude that informed the place.

And then the wind brought smoke from the gorge, which set her choking and folding her hood across her nose, while Carmil made disgusted faces and Egin scowled.

Gory came flying back with the other two outriders close behind, all wide-eyed and harried-looking. "Come!" Gory called tersely. "Ride with me. Only . . . come."

Amalian hesitated, then tossed the reins to Egin as the boy switched deftly from saddle to wagon seat. She mounted nigh as easily, flinging a leg across Skipstone's back with relaxed familiarity. An instant later they were galloping.

"I could explain," Gory muttered. "It'd be simpler if the guard did."

Amalian started to remind him that there was a time for silence and a time for speech, and then she saw the guard.

It was a woman, no older than herself and possibly younger. She wasn't in the tower, nor even atop the gatehouse that barred entrance to the forecourt; rather, she slumped like a door page just inside the gatehouse's portcullised entry arch, as though her duty no longer mattered.

She was dressed appropriately, in North Gorge heraldry--cloak of black and deep green slashed with silver, over the blood red tunic of War-Hold--but the cloak was dark with stains that mirrored the shadows beneath what should've been remarkably pretty gray eyes. A naked sword with War-Hold's plain barred hilt rested across her mail-clad thighs, but Amalian doubted she had the strength to use it--not that she would ever have had much need. Eron, after all, was civilized.

Wordlessly, Amalian dismounted and strode to within the armspan politeness proscribed. "Greetings," she said formally. "I am Amalian of Clan Eemon of Stonecraft, out of Stone-Hold-Winter. I hope the Dark has favored you and that the Light favors you twice and thrice again."

The guardswoman stared at her unblinking, as though she barely heard. Sickness, Amalian thought--or bone-tired weariness. Which, now that she looked, seemed more likely.

"Greetings . . . Amalian, or whatever you said," the woman mumbled in a raspy whisper. "If you seek Tir-Mil, you seek that which will please you little to find. Which some of you, by law of its council, are forbidden to enter."

Amalian's brow furrowed in a mix of anger and concern. She folded her arms across her breast, letting her cloak fall free to frame what could be, when she chose, an impressive figure. "It would be best if you spoke plainly."

"Plainly, then," the guardswoman gritted. "Plague."

Amalian flinched back a step. A people who lived so close together so much of the year must fear such things indeed. "Plague," she echoed numbly.

The woman nodded. "A new plague, the cure for which no one can discover. It arrived from the south, with the last trek before the Deep. Beyond that, we know little for certain. The winter holds--we pray--have been spared. But communication has all but collapsed. I have heard nothing from Tir-Mil for four days--and yet I dare not return."

Amalian felt heartsick, not only for her dashed hopes--though surely there'd be some way to risk the gorge--but also for the despair on this woman's face, which she knew was reflected a thousandfold elsewhere.

To her surprise, Gory spoke. "We found a dead man--"

"It begins as an itch in the ears, nose, and privates," the guard broke in tonelessly, "more often in men than women. The itch grows worse, and no potion or balm can cure it. In time it grows strong enough to drive men mad. Often, they attack each other or carve out their own ears and noses--and other things. I've heard more than one say that their brains were being eaten from within."

"And . . . women?" Amalian breathed.

The guard wouldn't meet her stare. "It . . . attacks the female parts and womb. We bleed uncontrollably. Those with child miscarry--or worse. It's feared those who survive will conceive no more."

Amalian shuddered. "And how many do survive?"

The woman shrugged. "A few. We don't know why, though the healers have tried everything. When I came here, it had taken one in three of the men, and maybe one in nine of the women. Mostly younger women."

Amalian's eyes narrowed. "Men--or males?"

"Men," the guardswoman answered. "Children are rarely afflicted. The weavers, however--"

Amalian looked troubled. "Weavers . . ."

Gory scowled at her. "What are you thinking?"

Amalian shook her head uncertainly. "That there might be a connection. Weavers to wool to sheep to those dead sheep we saw."

Gory stroked his chin. "And sheep are driven north with the season, so that the cold may thicken their coats."

"And this plague began in the south."

The guard plucked at her cloak, which, Amalian noted, was thrice-woven sylk, not the wool she'd have expected. "That much we do know, but little more. No one is allowed to wear wool--and that was only decided four days ago. Since then, I've had neither word nor relief."

Amalian scowled. "So what you are telling us is that we advance at our own risk. Surely you know some of us will dare the gorge. Many have family there."

The guard didn't move. "The Law I am given is this: Women may enter at their peril. Men may not until the plague runs its course."

"Damn!" Amalian spat, spinning 'round to glare at Gory as though it were all his fault. His face, too, was hard and grim. Then again, he had kin in Tir-Mil; she didn't.

"You lead the trek," he said simply. "You don't lead the people. You've brought them where they need to go and that's sufficient. What they do as concerns this plague is their decision."

The glare softened not a whit. "And you, husband?"

"I value my life. And I'd prefer that my children have a father."

"Well," Amalian sighed, "I'll alert the trek."

* * *

Egin loved a mystery. Close behind that, he had what his mother had always called a reckless fascination with danger. It was therefore inevitable that he'd catch wind of this plague and the fact that entire halls were being systematically closed up and torched down in North Gorge, not to mention the people who dwelt in them--once they'd died. And that, he decided, embraced both elements. There was the puzzle of what had brought this contagion, how it was spread, why some survived once it had run its course, and the greater enigma of why it singled out men. And there was the thrill of the forbidden.

The guard had said men were banned, period (as though she'd strength to enforce such a thing alone), and that women went of their peril.

Nothing, precisely, had been said about boys. And while he wasn't exactly a boy anymore--not in height, hairiness, or (as he'd happily discovered one cold winter night back in Stone) the ability (in theory) to beget children--still, he was not so far along that rather-too-responsible road that anyone actually expected to find him there. Which meant he'd get away with as much as he could for as long as he could, and damned be the consequences.

So it was that shortly after first-moon, he left his bedroll beneath his parents' caravan and ambled off in the direction of the livestock picket, officially to add his excreta to what was already stinking there. Happily, that stench had resulted in the packhorses and wagon-cattle being billeted downwind--which was to say between the camp, with its circled wagons and too-bright fires, and the gorge. And more happily, the fact that they were first trek down this season meant that the grass hereabouts hadn't been grazed to stubble; indeed, was waist high on him and afforded excellent cover. Add a dull tan cloak and hair still spiky from sleep, and one had a recipe for stealth.

Except that his sister seemed to have heard him (he could tell it was her by the whistle in her breath when she panted) and tagged along. And since he knew from experience that she would demand to accompany him and would raise an Eight's-awful cry if denied, he held his tongue when that tawny-topped shape burst through the grass beside him, clad in riding leathers, and with a face that far too closely mirrored his mother's when anger sat upon her like a mountain gathering thunder.

"You're a fool!" Carmil hissed. "People are dying down there!"

He tried not to show his fear as he paused for her. "I'm only going to the edge--no farther down than I have to in order to see--"

"What?"

"Buildings burning. People . . . dying. I dunno. Excitement! Anything besides Mother and Father and this wretched trek!"

"You're a man, Egin. Men are forbidden."

He laughed at her. "Last night you told me I was a boy. You can't have it both ways."

"Neither can you! I bleed; you squirt. That's what adults say marks the line."

"But they don't see those things; therefore they don't think about them; therefore they don't act on them. Besides, I say it's responsibility makes the difference, which is the same as accepting risk."

Carmil started to reply, then clearly thought better of it. "If you die, I'm not going to cry!"

"Wouldn't want you to," Egin sniffed, and strode off through the grass toward the gorge.

They took pains to avoid the trek road, which terminated in another tower, poised right on North Gorge's rim, where the river road came in from the south. It was deserted, which was both odd and frightening. But there were always more ways down than one, and it took barely another finger's scouting to locate a trail that snaked along the cliff to the floor of the gorge, a shot below.

Trouble was, it didn't give much of a view of Tir-Mil, North Gorge's only true city. It did, however, reveal the burning. What looked like boats--ships, even--had been set alight and left to float down the river that divided the fourshot-wide gash in the land. Maybe there was a better view lower down. As best Egin could tell, the trail ran among boulders, scraggly trees, and what might be a ruin, tending always west. This had the sense of a place that had once been important but fallen out of use.

"Egin, no!" Carmil warned as he made to descend. At least the pavement was still solid: plain flat stones set without mortar, but decent work all the same.

And sure enough, a wall jagged across the trail, with evidence of crenellations along its top, while a whole shattered tower clung to the cliff on the right. More interesting was the empty archway that spanned the trail--though even Egin hesitated upon entering. It was really dark in there.

"Egin!" Carmil snapped.

"Just through here and I'll stop," Egin retorted. And though he had actually been considering a retreat, there was no way he'd not dare the barrier now.

Steeling himself, he took a deep breath. And had not gone two steps into the blackness--not far enough for his eyes to adjust--when he tripped over something soft. He screamed. The cry cracked halfway through, in a most-unmanly fashion, yet he screamed again when his hand brushed another hand--and not Carmil's.

"Cold!" he yelped, even as he scrambled backward toward the arch.

Abruptly, he was up and running, grabbing Carmil on the way, and not stopping until they'd regained the rim.

"See anything?" his sister challenged when he paused there, winded from that long, mad scramble. She was barely panting.

"Dark!" Egin gasped. "And a . . . dead man."

Carmil's eyes narrowed, exactly like their mother's. "Dead of what? And how long?"

"I don't know! He was still soft. And he didn't smell."

Carmil glared at him, and most especially at his nice wool cloak. "Leave that here," she commanded. "We'll have to ask Mother what to do about it."

"I'll freeze!" Egin protested, hugging himself. But he unclasped the garment and let it fall.

"The price of disobedience," Carmil snorted. "But I'll let you off easy. You can tell Mother--or I will."

"In the morning."

A reluctant nod.

Egin rehearsed that telling all the way back to the camp. And he was still rehearsing when he crept back into his bedroll and snugged the blankets under his chin. A layer of padded fabric lay between him and the trampled sheep grass around the caravan; even so, the broken stems tickled his ear. He scratched it, then the other, which had decided to protest in sympathy. And sneezed--likely from the grass pollen that was already scenting the wind.

He awoke to find his head in agony and his ears filled with an insidious tickle. In fact, he itched pretty much everywhere--his scalp, his armpits, his groin, even inside his nose.

By midday he'd clawed himself raw and Amalian had dismissed the rest of the trek under command of her second, with one blood-chilling word.

Plague.

Egin had the plague.

By sunset, he was babbling incoherently, and they'd had to tie his hands.

Two days later, while the year's final dusting of snowflakes drifted down upon breakfast, he died.

Nor was he the last.

It had snowed as late as yester morn: thick, heavy flakes that had come wafting out of the northwest, as though the mountains in Angen's Spine were airing out their linens for the Light. Which, she supposed, made her and the trek she mastered among the larger, more recalcitrant motes of accumulated detritus. If The Eight dwelt in those gloomy peaks behind her, which she doubted--or if the rocks themselves were subtly alive, which some of Common Clan averred--they'd have to rise early indeed to loathe the cold season as much as she.

Oh, it had been beautiful enough in Stone-Hold-Winter, where the Fateing had sent her last Dark Half. The head-high drifts had made a fabulous backdrop for the statuary in the forecourt: warriors this rotation, carved in ruddy catlinite that contrasted nicely with the dark green hollies. Still, the cliffs and crags so prevalent thereabouts were harsh, naked rock that had as its primary virtue its many grades and colors, most of which were good for carving--which Amalian had spent all winter doing, and which was another thing she wouldn't miss with the turning of the year.

At least she hadn't been cold. Some of the winter holds were absolutely frigid, in spite of the steam-springs with which they were heated. Besides, Gory had been posted with her, and he was furry enough to keep several people warm--even through those wild solstice storms when three strong sets of walls and doors between living quarters and the cold without failed to stave off winter's fingers.

But she'd missed people, curse it! People in all their variety--any people beyond the same double-hundred-odd she'd seen day in and day out at the hold. And over half of those were her kin, whom she saw most of the year anyway.

Which was why, when Stone-Hold's weather-witch predicted an early spring and the Ekkon River broke through its ice a whole eight-day sooner than expected, she'd determined to take the risk.

So far it had been worth it, with far more color in the first-blooms than usual. Why, the gold stars that named this place almost glowed, and the ferns and bracken were particularly bright and frothy in the hollows among the pines. And the skies! Clear for days (yester morn notwithstanding) and so blue she wanted to reach up and chip away a chunk to carve into something precious.

Something for the twins, perhaps. Carmil and Egin: girl and boy. Thirteen now, and poised on the chisel blade between the children they'd been last Sundeath, when the journey north had begun, and the adults they were fast becoming. Both were a hand taller than when they'd left the lowlands, and Carmil had breasts and a woman's bleeding. Egin's voice was shifting so that his singing, which had been so sweet, was now rather more like croaking. And Gory, who'd seen him daily in the baths, had confided that their little boy now had hair in all men's places--matching that on his head, which was the same red-lit black as his sire's. Carmil's mirrored Amalian's own rare tawny gold.

She wondered where they were now. Riding ahead with Gory, perhaps? Or back swapping tales with the braver folk from Oak, who'd swelled their ranks that morning? She envied them--the children their freedom, the Oak folk their proximity to the northmost of the gorges where the bulk of clan, craft, and kin spent Eron's too-brief summers. It was to that cleft in the coastal plateau that Amalian led the trek now, through melting drifts of knee-deep snow. If luck rode with them, some of them would sleep in their own beds tonight, which would be change enough from the crowded chaos of the way stations that marked the nights between holds, halls, and gorges.

Sighing, she reached back to flip up her cloak's fur-lined hood. A breeze had come whipping out of the gap ahead, and she wondered if the twinge troubling her knees as she resettled them was merely token of a winter's inaction or the first insidious gnawings of old age.

Not the latter, she prayed. She wasn't far past thirty, and the sixty more years she expected to attain would be no great joy if her joints chose to ache through most of them.

And then the wind shifted, riding in from the south, bringing with it a hint of warmth that stirred her heart out of all proportion to its intensity.

But it brought other things as well: the scent of death, and, so faint as to be barely discernible, the scent of burning.

* * *

"I smell death," Amalian informed her husband, reining back the team: golds from Arsten, which had been part of her wedding dower from Gory's clan, who bred them.

Gory slapped his fractious gray gelding and nodded, his breath making blizzards in the air, riming the beard that framed his narrow, blue-eyed face. His cloak twitched in the wind. "Sheep," he grunted, as though that explained everything.

Amalian raised a brow. Gory was a fine man and an excellent mate--and said about ten words an eighth, as though he'd been born with a fixed allotment and treasured them like his clan treasured wagon-cattle.

"Which I presume belong to somebody," Amalian sighed, thinking that perhaps she might get a better account from the spindly pines that flanked the road to the left, or the rough-shelved slate cliffs slanting up to the right.

Gory grimaced. "Haven't been dead long, and there's only two. Margil's spent some time with the sheep folk and says the clan clips on their ears mark them as belonging to a small sept-hall on the south rim of North Gorge."

"A good day's ride from here."

Gory nodded.

"Wolves, then? Or birkits? Or--" She refused to name the other, because there was supposed to be no other. Wisdom said it was too cold for geens--man-sized lizard-things that walked on their hind legs--north of South Gorge. But Amalian wondered. Wisdom also said they were stupid as snakes, and she knew that was a lie.

Gory shrugged. "Just dead. A little rotten, no sign of violence."

"How long?"

Another shrug. "Thawed maybe two days. Beyond that, the only way of knowing is if we had a female, to check the unborn. They tend to conceive close to the same time."

"Lucky for us--if we had one," Amalian snorted. "Still, livestock escapes. And escaped livestock often dies."

"Aye," was Gory's sole reply.

* * *

By midday they'd crested Gold Star Gap and were on the last long winding slope before the road poured them out on the plains southeast below them: a patchwork of waving sheep grass and lingering snow, framed by the tips of the flanking pines. By midafternoon North Gorge should be in sight. By sunfall, they should be well on their way to Tir-Mil at the bottom.

But somehow she was uneasy. Not one person in the hundred had offered anything useful about the dead sheep, and they'd seen fifteen now. Speculation over them had been curtailed when they'd found the dead man.

It had been Gory (again) who'd discovered him--poor Gory, whose draw it had been to lead the day's outriders. The man had been dead at least eight days, and scavengers had been at him, so that it was hard to tell much save that he'd sheltered at Sharp Stone Station to bathe in the waters there and succumbed--naked--on the deep pool's stony marge. Heart freeze was possible. Heat could do that, and it was a very hot spring (and one Amalian had looked forward to sampling before their final approach). As best they could tell, the man had been in his early twenties. And, by the clothing flung about and ravaged--likely by the same beasts that had gnawed away his insides--he'd come from a prosperous clan. Beyond that, he'd been unremarkable. Black-haired, lightly bearded, fairly hairy, fit, and of the middle height and slim build typical of the Eronese. His clan tattoo, which would have revealed much, had been devoured along with most of his shoulder. Or scratched away, for the bulk of the man's intact skin was covered with long, deep furrows. He'd hacked off his hair, too, and not neatly, though men often did that near the end of the Dark.

It was another mystery. Amalian had ordered his body wrapped in oiled canvas and stored in the rearmost wagon. Burning would come later, when they'd determined his identity.

* * *

Four sun-hands later, they'd found a dozen more sheep, dead exactly as the others, but clipped to a different clan. And while that disturbed Amalian, it didn't truly concern her. By nightfall they'd be in Tir-Mil, where'd there'd be people whose duty it was to attend such things. She was merely the messenger.

What did disturb her was the fact that they could see the gorge now: a dark slash on the horizon, with the perpetual veil of steam rising out of it. But that steam was laced with darker vapors, which could only be the smoke of copious burning.

She smelled it, too, as she had that morning. But now it held a sharp, sweet tang she didn't like. If she didn't know better--if such things hadn't been rendered impossible by unshakable oaths between clan and craft--she'd have sworn war ravaged the gorge.

But that was absurd.

Besides, the road was flattening, the pines falling away to either side, and there was more waving grass ahead than melting snow, and that made her heart sing and fly.

The children sang as well--when they deigned to ride beside her: Carmil in her usual clear soprano, Egin in a cracky, pretentious boy-bass. It was a new song, too, one someone at Oak had contrived over the Deep, and seemed to involve a drunken man trying to sleep with women who were not always women. So much for her children's innocence. Egin fairly glowed. She wondered if that spotty glitter along his jaw was the first outpost of stubble.

Three hands later, they crested a rise and saw the guard station sprawling across the road ahead, maybe a shot from the gorge's northeast rim. Like most such structures built in High King Kryss's time, it was utterly unadorned and of the prescribed configuration: a single square tower five levels high, with smooth, trapezoidal sides and a flat roof. Each side fronted a square, walled courtyard marked by a two-story gatehouse, and the whole complex was enclosed by a lower wall to form a square within a cross within a square when viewed from above. The walls were thick, the stonework set with such impeccable skill as to show only hair-fine joins, so that neither foe nor winter could claim a hold. With shots of open country around, the former was unlikely; the latter a foregone conclusion.

Usually, though, such places were alive with people going about their tasks like ants upon a hill. And while Amalian knew that she'd come upon them days before expected, that offered no explanation for the air of decrepitude that informed the place.

And then the wind brought smoke from the gorge, which set her choking and folding her hood across her nose, while Carmil made disgusted faces and Egin scowled.

Gory came flying back with the other two outriders close behind, all wide-eyed and harried-looking. "Come!" Gory called tersely. "Ride with me. Only . . . come."

Amalian hesitated, then tossed the reins to Egin as the boy switched deftly from saddle to wagon seat. She mounted nigh as easily, flinging a leg across Skipstone's back with relaxed familiarity. An instant later they were galloping.

"I could explain," Gory muttered. "It'd be simpler if the guard did."

Amalian started to remind him that there was a time for silence and a time for speech, and then she saw the guard.

It was a woman, no older than herself and possibly younger. She wasn't in the tower, nor even atop the gatehouse that barred entrance to the forecourt; rather, she slumped like a door page just inside the gatehouse's portcullised entry arch, as though her duty no longer mattered.

She was dressed appropriately, in North Gorge heraldry--cloak of black and deep green slashed with silver, over the blood red tunic of War-Hold--but the cloak was dark with stains that mirrored the shadows beneath what should've been remarkably pretty gray eyes. A naked sword with War-Hold's plain barred hilt rested across her mail-clad thighs, but Amalian doubted she had the strength to use it--not that she would ever have had much need. Eron, after all, was civilized.

Wordlessly, Amalian dismounted and strode to within the armspan politeness proscribed. "Greetings," she said formally. "I am Amalian of Clan Eemon of Stonecraft, out of Stone-Hold-Winter. I hope the Dark has favored you and that the Light favors you twice and thrice again."

The guardswoman stared at her unblinking, as though she barely heard. Sickness, Amalian thought--or bone-tired weariness. Which, now that she looked, seemed more likely.

"Greetings . . . Amalian, or whatever you said," the woman mumbled in a raspy whisper. "If you seek Tir-Mil, you seek that which will please you little to find. Which some of you, by law of its council, are forbidden to enter."

Amalian's brow furrowed in a mix of anger and concern. She folded her arms across her breast, letting her cloak fall free to frame what could be, when she chose, an impressive figure. "It would be best if you spoke plainly."

"Plainly, then," the guardswoman gritted. "Plague."

Amalian flinched back a step. A people who lived so close together so much of the year must fear such things indeed. "Plague," she echoed numbly.

The woman nodded. "A new plague, the cure for which no one can discover. It arrived from the south, with the last trek before the Deep. Beyond that, we know little for certain. The winter holds--we pray--have been spared. But communication has all but collapsed. I have heard nothing from Tir-Mil for four days--and yet I dare not return."

Amalian felt heartsick, not only for her dashed hopes--though surely there'd be some way to risk the gorge--but also for the despair on this woman's face, which she knew was reflected a thousandfold elsewhere.

To her surprise, Gory spoke. "We found a dead man--"

"It begins as an itch in the ears, nose, and privates," the guard broke in tonelessly, "more often in men than women. The itch grows worse, and no potion or balm can cure it. In time it grows strong enough to drive men mad. Often, they attack each other or carve out their own ears and noses--and other things. I've heard more than one say that their brains were being eaten from within."

"And . . . women?" Amalian breathed.

The guard wouldn't meet her stare. "It . . . attacks the female parts and womb. We bleed uncontrollably. Those with child miscarry--or worse. It's feared those who survive will conceive no more."

Amalian shuddered. "And how many do survive?"

The woman shrugged. "A few. We don't know why, though the healers have tried everything. When I came here, it had taken one in three of the men, and maybe one in nine of the women. Mostly younger women."

Amalian's eyes narrowed. "Men--or males?"

"Men," the guardswoman answered. "Children are rarely afflicted. The weavers, however--"

Amalian looked troubled. "Weavers . . ."

Gory scowled at her. "What are you thinking?"

Amalian shook her head uncertainly. "That there might be a connection. Weavers to wool to sheep to those dead sheep we saw."

Gory stroked his chin. "And sheep are driven north with the season, so that the cold may thicken their coats."

"And this plague began in the south."

The guard plucked at her cloak, which, Amalian noted, was thrice-woven sylk, not the wool she'd have expected. "That much we do know, but little more. No one is allowed to wear wool--and that was only decided four days ago. Since then, I've had neither word nor relief."

Amalian scowled. "So what you are telling us is that we advance at our own risk. Surely you know some of us will dare the gorge. Many have family there."

The guard didn't move. "The Law I am given is this: Women may enter at their peril. Men may not until the plague runs its course."

"Damn!" Amalian spat, spinning 'round to glare at Gory as though it were all his fault. His face, too, was hard and grim. Then again, he had kin in Tir-Mil; she didn't.

"You lead the trek," he said simply. "You don't lead the people. You've brought them where they need to go and that's sufficient. What they do as concerns this plague is their decision."

The glare softened not a whit. "And you, husband?"

"I value my life. And I'd prefer that my children have a father."

"Well," Amalian sighed, "I'll alert the trek."

* * *

Egin loved a mystery. Close behind that, he had what his mother had always called a reckless fascination with danger. It was therefore inevitable that he'd catch wind of this plague and the fact that entire halls were being systematically closed up and torched down in North Gorge, not to mention the people who dwelt in them--once they'd died. And that, he decided, embraced both elements. There was the puzzle of what had brought this contagion, how it was spread, why some survived once it had run its course, and the greater enigma of why it singled out men. And there was the thrill of the forbidden.

The guard had said men were banned, period (as though she'd strength to enforce such a thing alone), and that women went of their peril.

Nothing, precisely, had been said about boys. And while he wasn't exactly a boy anymore--not in height, hairiness, or (as he'd happily discovered one cold winter night back in Stone) the ability (in theory) to beget children--still, he was not so far along that rather-too-responsible road that anyone actually expected to find him there. Which meant he'd get away with as much as he could for as long as he could, and damned be the consequences.

So it was that shortly after first-moon, he left his bedroll beneath his parents' caravan and ambled off in the direction of the livestock picket, officially to add his excreta to what was already stinking there. Happily, that stench had resulted in the packhorses and wagon-cattle being billeted downwind--which was to say between the camp, with its circled wagons and too-bright fires, and the gorge. And more happily, the fact that they were first trek down this season meant that the grass hereabouts hadn't been grazed to stubble; indeed, was waist high on him and afforded excellent cover. Add a dull tan cloak and hair still spiky from sleep, and one had a recipe for stealth.

Except that his sister seemed to have heard him (he could tell it was her by the whistle in her breath when she panted) and tagged along. And since he knew from experience that she would demand to accompany him and would raise an Eight's-awful cry if denied, he held his tongue when that tawny-topped shape burst through the grass beside him, clad in riding leathers, and with a face that far too closely mirrored his mother's when anger sat upon her like a mountain gathering thunder.

"You're a fool!" Carmil hissed. "People are dying down there!"

He tried not to show his fear as he paused for her. "I'm only going to the edge--no farther down than I have to in order to see--"

"What?"

"Buildings burning. People . . . dying. I dunno. Excitement! Anything besides Mother and Father and this wretched trek!"

"You're a man, Egin. Men are forbidden."

He laughed at her. "Last night you told me I was a boy. You can't have it both ways."

"Neither can you! I bleed; you squirt. That's what adults say marks the line."

"But they don't see those things; therefore they don't think about them; therefore they don't act on them. Besides, I say it's responsibility makes the difference, which is the same as accepting risk."

Carmil started to reply, then clearly thought better of it. "If you die, I'm not going to cry!"

"Wouldn't want you to," Egin sniffed, and strode off through the grass toward the gorge.

They took pains to avoid the trek road, which terminated in another tower, poised right on North Gorge's rim, where the river road came in from the south. It was deserted, which was both odd and frightening. But there were always more ways down than one, and it took barely another finger's scouting to locate a trail that snaked along the cliff to the floor of the gorge, a shot below.

Trouble was, it didn't give much of a view of Tir-Mil, North Gorge's only true city. It did, however, reveal the burning. What looked like boats--ships, even--had been set alight and left to float down the river that divided the fourshot-wide gash in the land. Maybe there was a better view lower down. As best Egin could tell, the trail ran among boulders, scraggly trees, and what might be a ruin, tending always west. This had the sense of a place that had once been important but fallen out of use.

"Egin, no!" Carmil warned as he made to descend. At least the pavement was still solid: plain flat stones set without mortar, but decent work all the same.

And sure enough, a wall jagged across the trail, with evidence of crenellations along its top, while a whole shattered tower clung to the cliff on the right. More interesting was the empty archway that spanned the trail--though even Egin hesitated upon entering. It was really dark in there.

"Egin!" Carmil snapped.

"Just through here and I'll stop," Egin retorted. And though he had actually been considering a retreat, there was no way he'd not dare the barrier now.

Steeling himself, he took a deep breath. And had not gone two steps into the blackness--not far enough for his eyes to adjust--when he tripped over something soft. He screamed. The cry cracked halfway through, in a most-unmanly fashion, yet he screamed again when his hand brushed another hand--and not Carmil's.

"Cold!" he yelped, even as he scrambled backward toward the arch.

Abruptly, he was up and running, grabbing Carmil on the way, and not stopping until they'd regained the rim.

"See anything?" his sister challenged when he paused there, winded from that long, mad scramble. She was barely panting.

"Dark!" Egin gasped. "And a . . . dead man."

Carmil's eyes narrowed, exactly like their mother's. "Dead of what? And how long?"

"I don't know! He was still soft. And he didn't smell."

Carmil glared at him, and most especially at his nice wool cloak. "Leave that here," she commanded. "We'll have to ask Mother what to do about it."

"I'll freeze!" Egin protested, hugging himself. But he unclasped the garment and let it fall.

"The price of disobedience," Carmil snorted. "But I'll let you off easy. You can tell Mother--or I will."

"In the morning."

A reluctant nod.

Egin rehearsed that telling all the way back to the camp. And he was still rehearsing when he crept back into his bedroll and snugged the blankets under his chin. A layer of padded fabric lay between him and the trampled sheep grass around the caravan; even so, the broken stems tickled his ear. He scratched it, then the other, which had decided to protest in sympathy. And sneezed--likely from the grass pollen that was already scenting the wind.

He awoke to find his head in agony and his ears filled with an insidious tickle. In fact, he itched pretty much everywhere--his scalp, his armpits, his groin, even inside his nose.

By midday he'd clawed himself raw and Amalian had dismissed the rest of the trek under command of her second, with one blood-chilling word.

Plague.

Egin had the plague.

By sunset, he was babbling incoherently, and they'd had to tie his hands.

Two days later, while the year's final dusting of snowflakes drifted down upon breakfast, he died.

Nor was he the last.

Recenzii

Praise for Bloodwinter:

"Deitz's unusual setting and strong, magnetic characters bode well for this new series."

--Publishers Weekly

"A complex tale...a solid addition to most fantasy collections."

--Library Journal

"Deitz's skill at crafting a complex tale of men and women driven by warring emotions and rival ambitions anchors his fantasy visions in the reality of human experience."

--Library Journal

"Both villainy and heroism go beyond stereotype [in] a well-crafted work that explores the nature of art."

--Locus

"Tom Deitz is a fine storyteller in the tradition of the Southern mountains...with all its legends and magic transported from afar. Like his forebears, he can make magic with words."

--Sharyn McCrumb, New York Times bestselling author of The Ballad of Frankie Silver

"Once again, Tom Deitz has proven himself a master of the fantasy genre. He has created a detailed, realistic world, characters who are both engaging and believable, and a compelling, fast-moving story that draws the reader in from the first page."

--John Maddox Roberts

"Deitz has always been a superb fantasist, but he's outdone himself in this richly developed, character-driven story!"

--Josepha Sherman

"Deitz's unusual setting and strong, magnetic characters bode well for this new series."

--Publishers Weekly

"A complex tale...a solid addition to most fantasy collections."

--Library Journal

"Deitz's skill at crafting a complex tale of men and women driven by warring emotions and rival ambitions anchors his fantasy visions in the reality of human experience."

--Library Journal

"Both villainy and heroism go beyond stereotype [in] a well-crafted work that explores the nature of art."

--Locus

"Tom Deitz is a fine storyteller in the tradition of the Southern mountains...with all its legends and magic transported from afar. Like his forebears, he can make magic with words."

--Sharyn McCrumb, New York Times bestselling author of The Ballad of Frankie Silver

"Once again, Tom Deitz has proven himself a master of the fantasy genre. He has created a detailed, realistic world, characters who are both engaging and believable, and a compelling, fast-moving story that draws the reader in from the first page."

--John Maddox Roberts

"Deitz has always been a superb fantasist, but he's outdone himself in this richly developed, character-driven story!"

--Josepha Sherman